By Stephen Brookes

The Washington Post, September 23, 2007

It's a gritty afternoon in a gritty parking lot in a gritty South Baltimore neighborhood, and the crowd is starting to fade. For the past five hours at this human rights rally, poets and rappers have been taking the stage to one-up one another's outrage, and now even the most anguished cries -- "the beast of the United States is eating wherever it wants!" -- are met with little more than polite nods. The sky's getting dark, the slogans are getting tired, and you can see people thinking that the struggle for justice should maybe just take the night off.

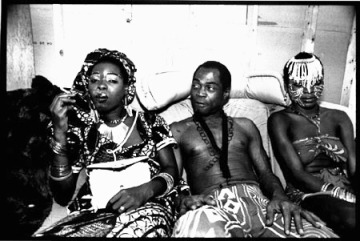

Fela Anikulapo Kuti, originator of Afrobeat

But then a new band takes the stage -- and suddenly a driving pulse erupts, powerful and irresistible. It's unlike anything else at the rally that day. This is no clumsy rapping or earnest revolutionary poetry -- this music has the drive of 1970s funk, the subtle rhythms of Yoruba tribal music, the fire of Ghanaian highlife. And when the five-piece horn section kicks in, driving the energy higher, everybody -- everybody -- starts dancing.

"We're here tonight to see people get active!" shouts the band's leader, pumping a fist in the air. "Otherwise, it's all over!"

The music is Afrobeat -- a fiery brand of political dance music pioneered in the 1970s by the Nigerian activist Fela Kuti -- and the group is Chopteeth, a 14-piece big band that's part of an Afrobeat revival across the United States. Thirty years ago, Afrobeat was the most important new music in Africa, fusing James Brown-style funk, African rhythms and urgent messages of political confrontation. But it never became an international phenomenon like reggae, and nearly vanished a decade ago when Kuti died.

Over the past few years, though, this profoundly African music has found a new home -- in America.

"There's a surge of interest now in Fela's music," says guitarist Michael Shereikis, 38, who leads the D.C.-based Chopteeth. "Virtually every song he wrote is a protest song, and they have a lot of resonance today. We do one song of his called 'Alagbon Close,' which is about torture in prisons -- a very timely thing to be singing about."

But building on Kuti's legacy is no easy task. A larger-than-life figure who famously married 27 women and battled a succession of military governments, Kuti was a maverick whose music was inseparable from his political life. Born in 1938 to a middle-class Nigerian family, he'd started as a fairly average, mainstream bandleader in Lagos in the 1960s. But after meeting the Black Panthers during a 1969 trip to Los Angeles, he quickly became radicalized -- and set out to change history.

Returning to Nigeria, Kuti reinvented himself. He adopted the name Anikulapo ("he who carries death in his pouch"), set up a radical commune called the Kalakuta Republic and began taking on Nigeria's military rulers with a new style of music he called Afrobeat. It was ferocious, satirical music, combining raw lyrics with a big horn section and lots of percussion. Kuti would spin songs out for half an hour or more, drawing people in with the seductive rhythms -- before delivering a sharp, devastating attack on the government.

Afrobeat made him famous, but it also set off riots and brought vicious retribution. Kuti suffered -- his commune was burned, his mother was thrown from a window, and he was arrested repeatedly on what most agreed were trumped-up charges. When he died in 1997, after years of harassment, more than a million people turned out in the streets to mourn him. And the music, tied so closely to the man, seemed to die with him.

An ocean away in Brooklyn, meanwhile, a young musician named Martin Perna was wondering why no one was picking up the torch. "It was tricky in the beginning to find anybody who even knew what this music was," says Perna, who went on to form the 12-member Afrobeat band Antibalas in 1998. "But Afrobeat was a way for me to merge my political convictions with my convictions as a musician. It's inherently a music of resistance and a music of struggle, and if you're going to reach people with any sort of message, you've got to put it to a beat."

Shereikis (l) and Mwalagho of ChopteethAntibalas (Spanish for "bulletproof") quickly won converts -- the band now puts on more than 100 shows a year in the United States, Canada, Europe and even Africa, and is widely considered the best Afrobeat band in the world.

Dozens more bands have been formed across the United States, raising the level of playing (many are conservatory-trained), writing new music and developing the style in surprising, inventive ways.

For Shereikis, the path to Afrobeat was a surprise even to himself. A self-taught guitarist, he'd been exposed to African music as a Peace Corps volunteer in the Central African Republic in the early 1990s. But he was working on a PhD in cultural anthropology from Tulane -- and contemplating a career in academia -- when bassist Robert Fox approached him in 2004 and suggested they start an Afrobeat band.

"I thought he was insane," says Shereikis. (In fact, the band takes its name from a Kuti song meaning "crazy person.") "But my one stipulation was that we mix it up with rumba, highlife, jazz and other kinds of music. We play a lot of Fela's music, but we're going in a new direction."

As the band has grown to include members such as Kenyan singer Anna Mwalagho, the superb trumpeter Justine Miller and reedman Mark Gilbert (who's played with everybody from the Temptations to Root Boy Slim), the influences have expanded even further. The band's first CD -- planned for release by the end of the year -- will be "a strange new crop of songs," says Shereikis.

Reinventing Afrobeat may be the key to its survival, its proponents say. The music is unlikely ever to enter the mainstream -- "there's too much stuff in Afrobeat for the market to dumb down," says Perna -- but if it's going to take root in American soil, it needs to adapt. The new players are hardly African firebrands. They tend to be American, white and mostly suburban. The music even seems to be turning into new, hybridized genre -- call it American Afrobeat -- with an agenda of its own.

"Most of the groups doing Afrobeat are either multicultural or predominantly white," says Perna, whose own background is Latino.

"How they address the privileges they enjoy -- male privilege, class privilege, skin color privileges -- will give American Afrobeat its depth; looking within themselves, rather than just pointing. Anybody can point a finger at George Bush, or the Iraq war, or police brutality, and write a song about it," he says. "But the real depth comes from examining these other systems of privilege. And we try to do that in our music."

And as far as Shereikis is concerned, the Afrobeat revival makes perfect sense -- even if it is happening in America.

"There's a lot of anger and frustration in the United States right now. So we try to think big, to address the macro political issues," he says. "The groove is important -- it's what keeps people feeling good and dancing. But the point of setting that stage is to get your message across."