By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • June 15, 2008

___________________________________________________________________________________

Salif KeitaThe horrific reports started streaming in from East Africa last year -- first in a trickle, then in a flood.

In Tanzania, a teacher was arrested for killing his own son, because the child had been born an albino. In an area around Lake Victoria, the corpse of another albino was found with all its limbs cut off; others turned up minus tongues or genitals, and earlier six albinos were killed for their skins, which were then displayed for sale. By some accounts, as many as 50 albinos in Tanzania alone have been killed in the past year -- their blood, hair and flesh destined for the magic potions of witch doctors.

“People kill albinos and chop their body parts, including fingers, believing they can get rich," Tanzania’s president Jakaya Kikwete said in a television address earlier this year. The fault, added Provincial Commissioner Luteni Kanali Issa, lay with witch doctors from all across Africa. “The influx of these traditional healers has contributed to mass deaths of albinos,” he said. “And soon they will be wiped out."

The reports are shocking, but they don’t surprise Salif Keita.

“This sort of thing has been happening for a long time, and it’s still going on,” says the Malian singer, speaking by phone from his home in Djoliba, near the capital of Bamako. “People do not understand about albinos – there are so many superstitions about them, because people are not educated.”

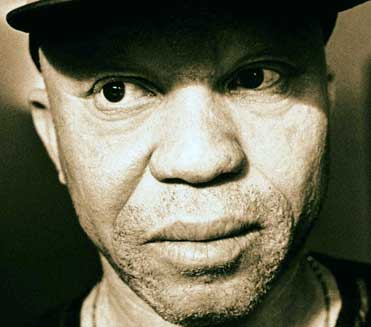

Keita should know – he’s an albino himself. At 58, the Afropop superstar (who appears at Lisner Auditorium this Friday) has become one of the most celebrated African musicians in the world, with a string of international hits. Now he’s using his considerable fame to change how albinos are treated in Africa, and to fight against the deep-rooted superstitions that can lead – as in the recent episodes in Tanzania – as far as murder.

Like most African albinos, Keita has been a social outcast virtually since the day he was born. The scion of a royal family (he’s a direct descendent of Sundiata Keita, the Mandinka warrior king who founded the Malian empire about 1240), Keita’s pink complexion and yellow hair shocked his father, who shunned him in his early years. His fragile skin meant he couldn’t work in the fields, and discrimination thwarted his ambition to become a teacher.

With few other options, he began to sing in the streets as a sort of modern-day griot, or wandering musician – a very low-caste occupation.

“In my family, it was not very easy to be a musician,” he says. “My family is the royal family, and the royal family makes war – they don’t sing.” But Keita’s albinism turned into a blessing. His songwriting talent and luminous, unmistakable tenor voice -- he’s widely known as “the Golden Voice of Africa -- began to attract notice, and he was recruited by a state-sponsored group called the Rail Band in 1970. Moving on a few years later to a band called Les Ambassadeurs, he began incorporating Malian influences into the Afro-Cuban music the band played.

But Keita’s albinism turned into a blessing. His songwriting talent and luminous, unmistakable tenor voice -- he’s widely known as “the Golden Voice of Africa -- began to attract notice, and he was recruited by a state-sponsored group called the Rail Band in 1970. Moving on a few years later to a band called Les Ambassadeurs, he began incorporating Malian influences into the Afro-Cuban music the band played.

The music caught on, and Keita’s fame began to spread. In 1977 he was awarded the National Order of Guinea by President Ahmed Sekou Toure, and in response he wrote the hugely successful song “Mandjou”, which tells the story of the Malian people. But political unrest was growing in Mali, and (as an outspoken critic of the government) he left the country, resettling in Paris in 1984.

And there things began to take off. Blending the traditional griot music of his childhood with influences from Guinea, the Ivory Coast and Senegal, as well as the music of Cuba and Portugal, Keita almost single-handedly launched the Afropop movement with the pioneering 1987 album “Soro.” Restless and inventive, he went on to release the jazz-influenced “Amen” (1991) and the more rock-oriented “Papa” in 1999, moving to a more acoustic and traditional sound with “Moffou” (2002) and the 2006 release, “M’Bemba” – winning six Grammy nominations along the way.

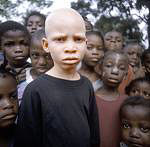

As his success grew, Keita was becoming increasingly concerned with the situation of Africa’s albinos. Albinism is an inherited genetic condition in which melanin – crucial to protecting the skin – is missing, causing pale complexion, light hair and vision problems. In the West, it’s not particularly common or noticeable (roughly 1 in 20,000 people have it in the US), but in some parts of Africa it affects as many as 1 in 1,100 people. And because it’s caused by a recessive gene (which can skip generations), an albino child can be born to black parents, causing confusion, suspicions of infidelity, and fears that the child is cursed.

“The biggest thing that people with albinism face is that they generally look different, particularly in cultures of color,” says Mike McGowan, director of the US-based National Organization for Albinism and Hypopigmentation. “And there’s an unfortunate part of human nature that shuns difference.”

With their pinkish skin and yellowish hair, Africa’s albinos stand out dramatically; they’re called derogatory names -- “ghosts” and “peeled potatoes” are some of the gentler ones -- and a range of bizarre myths have grown up around them. They’re often thought to have magical powers; some cultures, for instance, think albinos just vanish rather than actually die. Many of the superstitions are harmless, like the one that says drinking Fanta orange soda can lead to the conception of an albino baby. But others are more insidious: A recent rise in rapes of albino women is being attributed to a belief that sex with an albino can cure HIV-AIDS. While the social discrimination is often fierce, the main problem most African albinos face is simply staying alive. Since their skins lack protection against the brutal sun, skin cancer is a constant threat, with treatment expensive and often unavailable. Poor eyesight keeps many from finishing school, leading to perceptions that they are weak or mentally deficient.

While the social discrimination is often fierce, the main problem most African albinos face is simply staying alive. Since their skins lack protection against the brutal sun, skin cancer is a constant threat, with treatment expensive and often unavailable. Poor eyesight keeps many from finishing school, leading to perceptions that they are weak or mentally deficient.

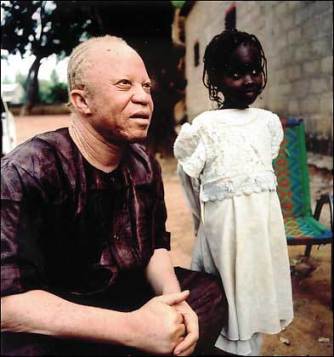

So in 1991, Keita helped to found a foundation called SOS Albinos, in Bamako, and returned permanently to Mali in 2004 to devote more time to the cause. He’s distributed glasses and thousands of tubes of free sunscreen to Mali’s albinos (one of the most practical steps to improve their condition), established a hospital for victims of skin cancer, and worked to help integrate them into society though education.

“They need help,” says Keita. “Many of their problems come from the sun, because many of them are farmers, and they get skin cancer. First, we gave them sunscreen, and then we built a hospital, because no one wanted to help them. But now we have people who will take care of them.”

Keita plans to expand his campaign across Africa, and recently launched the Salif Keita Global Foundation [www.salifkeita.org] to raise money for free healthcare and educational services. There are a few other support groups across the continent, including Tanzania’s Albino Society, the Albino Association of Zimbabwe and the Albino Association of Malawi, but they are marginally funded at best; few outside observers see any dramatic improvement coming in the lives of most albinos.

"Beyond finding the albinism gene, there's precious little research being done" to understand the condition or prevent new cases, says NOAH's McGowan.

But Keita remains optimistic.

“One day, there will be no more albinos. We’ll find a solution for it, so that when you’re born, you’re normal,” he says. “We will find a solution – I’m sure.”