By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • November 11, 2011

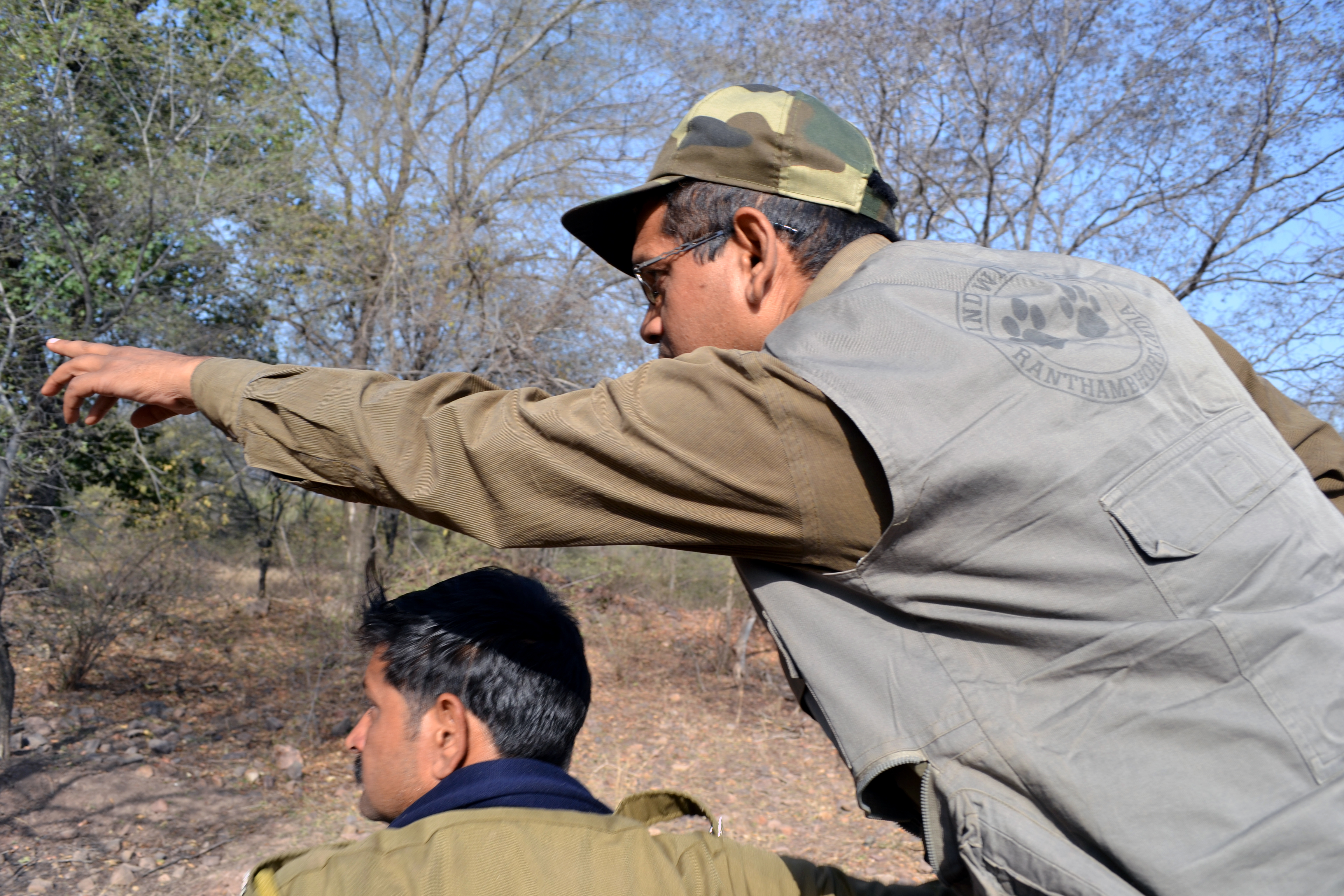

It’s just after dawn, and our Jeep is skidding down a steep, rocky track in the semi-darkness. We’re hanging on for dear life, when suddenly we brake to a halt and our guide leans over the side. He points to a paw print in the dust. It’s huge and amazingly detailed; you can almost see the claw marks.

“Tiger,” the guide whispers. “Very fresh.” We peer into the twisting acacia trees around us, the shadows that stretch in every direction. The guide makes a low rumbling noise in his throat. “Tiger mating call,” he says quietly.

“Is that . . . really wise?” a woman sitting next to me asks as he makes the sound again. The guide gives us a level look, then wags his head and breaks into a grin. “Tiger is a very intelligent animal,” he admits. “Hard to make him fool.” Five of us are packed into the low, open Jeep, and for the past hour we’ve been crisscrossing the dry hills of Ranthambhore National Park in northern India in search of the Royal Bengal tiger. So far, we haven’t had much luck, which isn't too surprising. Tigers have become almost impossible to find in the wild anymore; their numbers have been devastated over the past century, and fewer than 4,000 are left in the world.

Five of us are packed into the low, open Jeep, and for the past hour we’ve been crisscrossing the dry hills of Ranthambhore National Park in northern India in search of the Royal Bengal tiger. So far, we haven’t had much luck, which isn't too surprising. Tigers have become almost impossible to find in the wild anymore; their numbers have been devastated over the past century, and fewer than 4,000 are left in the world.

But India is one of the last places where wild tigers can still be seen. About half of the planet’s remaining tigers live here, and we’ve come to the Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve because it might be the richest -- and most beautiful -- of India’s 39 such reserves. With about 155 square miles of prime tiger country stretching over the hills of the Indian state of Rajasthan, it may, in fact, be the best place to search for tigers in the world.

Timing is everything when loking for wildlife, and we’d been picked up at our hotel at 5:30 that morning by our guide -- a tiger expert (and lawyer, curiously enough) named Mahesh Chaudhary -- and a few minutes later found ourselves in a knot of Jeeps at the ancient stone gate that leads into the reserve.

You can’t get into Ranthambhore without a reservation (fewer than 500 visitors are allowed in every day) and we have to wait for the rangers to check our names and tell us which zone we’ll be allowed into. This is a key question, and Mahesh has been a little anxious about it. Only about a quarter of the reserve is open to tourists, he tells us, and that area is divided into six zones, some of which are virtually tiger-free. But we get Zone 4, and Mahesh gives us a relieved smile. “A very good zone!” he says. “I think we will see a tiger today.”

Maybe. But we know that, realistically, the chances are slim. Most visitors, in fact, never get to see a single tiger. There are only about 35 in the whole reserve, and they tend to stay in a core area where humans are not allowed. Only a dozen or so live in the tourist zones, and they’re notoriously solitary creatures, spending most of their time hidden in the forest, sleeping. On the plus side, we’ve come in April; it’s the hot season, and many of the trees have lost their leaves, making tiger spotting easier. We might get lucky. But we know that at best, we’ll probably only get a distant glimpse.

The rangers wave us through the gate, and we set off up a twisting road into the park. Tigers aside, Ranthambhore is a spectacularly beautiful place, full of plunging gorges and jaw-dropping views surrounding the ruins of a 10th-century fort. We veer down a dirt track into the forest, and animals start to appear: a delicate sambar deer with upward-curving horns, black-faced lemur monkeys in the branches of a dhok tree, a herd of Chinkara gazelles on the ridge of a distant hill.

It's Edenic -- but it wasn't always so. Ranthambhore was a battleground for more than six centuries, the scene of one bloody invasion after another. In the 17th century, the area passed to the Maharajas of Jaipur, who turned it into a tiger-hunting reserve, and in 1955 the government made it a wildlife sanctuary. Since then, an astonishing array of animals has come to flourish, and as we lurch over the trails we come across the tracks of a sloth bear, see a pair of mongooses dart across the road, and watch a brilliantly colored kingfisher dive into a pond full of crocodiles. Egrets pose at the edge of a far-off marsh, and a peacock, startled by our jeep, lurches into the air with an indignant squawk.

But . . . no tigers.

You can hardly blame tigers for avoiding us, given that we’ve hunted them pretty close to extinction. Of the 40,000 Royal Bengals that roamed India a century ago, only about 1,760 remain — and they’re in deep, serious peril. The Sariska Tiger Reserve (less than 100 miles from Ranthambhore) lost all of its 26 tigers in 2006, most to poachers supplying markets in China and Tibet, where a pelt can reportedly fetch as much as $12,500 and the organs are sold for medicines and aphrodisiacs. The profit from a single animal can be as high as $50,000, and the risks are low. With that kind of price on their heads, it’s a wonder any tigers are left at all.

We’ve spent about two hours exploring the reserve, and Mahesh has guided us into a clearing to take a break when suddenly a high-pitched cry pierces the forest. He jumps up and stares into the trees. It’s the alarm call of a deer — a telltale sign that a tiger is around. Tigers prefer to hunt deer, Mahesh tells us, though they’ll eat monkeys and slow, easy prey such as frogs and peacocks.

“And Jeeps full of tourists?” someone asks. Dozens of people are killed by tigers every year, we’ve heard, and India has had its share of dangerous man-eaters, such as the notorious Champawat Tigress, who killed 436 people around the turn of the 20th century.

But Mahesh assures us that we’re in no danger, even though our open vehicle feels a bit like a serving tray, with us as the canapes. The tigers here have grown up with people around, he says, and if we got out of the Jeep they would probably just run away — though he urges us not to test the theory.

“We probably look like candy bars to them,” says someone in the back seat. “Crunchy on the outside, soft and chewy in the middle.” Mahesh admits that this is, in fact, sort of true. Humans can be appetizing to older tigers who have lost some of their teeth, since we lack shells, fur or fang-proof packaging of any kind. Plus, we’re slow. And not always particularly smart. Mahesh tells us that in fact someone was just killed in Ranthambhore: a local villager who went into the forest with his donkey to collect firewood. The tiger went for the donkey; the villager responded by throwing stones. The tiger took offense, and that was the end of the villager.

The deer cries again, and we follow the sound through the trees, emerging into a dry streambed where several other Jeeps and two lumbering, 20-seat vehicles called “canters” have pulled up, full of animal paparazzi like us. The sun is higher now and the heat is scorching, but we barely notice. Everyone has their lenses and high-powered binoculars aimed into a patch of tall grass 50 yards off the road, where one of the rangers has seen a bird fly off with a piece of meat in its mouth, a good sign that there’s been a kill. “Machali is in there; this is her territory,” Mahesh tells us in a hushed voice. “She would have made the kill last night and returned today to eat it.” Her name is officially T-16 (all the Ranthambhore tigers have these bureaucratic labels), but the rangers have given her a nickname taken from a distinctive pattern on her right cheek. “Machali,” it turns out, means “fish.”

“Machali is in there; this is her territory,” Mahesh tells us in a hushed voice. “She would have made the kill last night and returned today to eat it.” Her name is officially T-16 (all the Ranthambhore tigers have these bureaucratic labels), but the rangers have given her a nickname taken from a distinctive pattern on her right cheek. “Machali,” it turns out, means “fish.”

We creep up the dirt track, and suddenly Mahesh holds up his hand and points: Machali has appeared, gliding through the grass parallel to us about 30 yards away. She’s just a flash of stripes at first, her face a tan disk in the pale grass, and we hold our breath, expecting her to vanish into the trees. But suddenly she pauses and seems to sniff the air.

And then she starts walking toward us.

It’s hard to describe the feeling — the raw, elemental terror — of a tiger approaching you in the wild. A woman behind me has literally climbed on top of the person next to her, which gives you the general idea. Machali clears the long grass, and we can see her now in all her fearful symmetry. She’s magnificent — nine feet long and more than 300 pounds — and frighteningly powerful, gliding over the rock-strewn ground. Her eyes never leave us. Pausing by an acacia tree 30 feet away, she flicks her tail and gives us a long, cool look.

The only sound is the click of cameras and the faint whimpering of the woman behind me. Machali starts moving toward us again, and in a moment is so near that with a jump she’d be in the Jeep. Even Mahesh is looking alarmed. We can see into the tiger’s pale green eyes now, trace the labyrinth of marks that run, like hieroglyphics, across her face. It’s mesmerizing. No one can move — we’re caught in some kind of primal encounter, some primitive, brain-stem memory of being hunted in the forest before we were even human. Ten thousand years of civilization suddenly evaporate. We've become prey, pure and simple. And now, just 10 feet away, Machali stops and turns those otherworldly eyes on us — a cruel and distant god about to decide our fate.

And then. . . .

She yawns.

She yawns, and strolls almost casually between the Jeeps. The god isn’t interested in us at all, apparently; she just wants to cross the road, and we happen to be in the way. Her power, her terrible majesty seem to deflate as she ambles tamely among the vehicles. I look down and fumble with my camera for a second, strangely ashamed. We’ve diminished her with our presence. When I look back up, the tiger has vanished into the trees on the far side of the track. But a little later she reappears a hundred yards away, climbing across a rocky escarpment. Radiant in the morning sunlight, she makes her way down the rocks to a streambed below, and we lose her in the thick reeds where she’s gone to drink. But we catch one final glimpse as she turns and starts walking again, up the streambed and off into the distant hills. With every step away from us, she becomes more beautiful, more unfathomable, more strange and mysterious -- more the tiger of our imaginations.

When I look back up, the tiger has vanished into the trees on the far side of the track. But a little later she reappears a hundred yards away, climbing across a rocky escarpment. Radiant in the morning sunlight, she makes her way down the rocks to a streambed below, and we lose her in the thick reeds where she’s gone to drink. But we catch one final glimpse as she turns and starts walking again, up the streambed and off into the distant hills. With every step away from us, she becomes more beautiful, more unfathomable, more strange and mysterious -- more the tiger of our imaginations.

We stare after her, blinded by the immense light reflecting off the hills, until she’s gone.

•••••

(This article also appeared in The Seattle Times, The Columbus Dispatch, and USA Today.)

GETTNG THERE

Continental offers connecting flights from BWI Marshall to New Delhi starting at $1,328 round trip. From New Delhi, a train to Sawai Madhopur (the closest town to Ranthambhore National Park) takes about 51 / 2 hours.

WHERE TO STAY

The Oberoi Vanyavilas

Ranthambhore Road

011-91-7462-22-3999

www.oberoihotels.com

The superb Oberoi Vanyavilas is the best hotel in the area -- in fact, it was voted “best hotel in the world” by Travel + Leisure magazine in 2010, and it's easy to see why. With its luxurious tents, four-poster beds and bougainvillea-shaded gardens, it’s an unforgettable experience, and a perfect retreat after a dusty day in the tiger reserve. The standard rate is about $900 a night, but check for specials.

Taj Sawai Madhopur Lodge

Ranthambhore National Park Road

Sawai Madhopur

011-91-7462-22-0541

www.vivantabytaj.com

Part of the Vivanta by Taj group. Comfortable rooms run from $150 to $500 per night.

WHAT TO DO

Ranthambhore National Park

011-91-9212-77-7223

www.ranthamborenationalpark.com

Tigers are elusive, so I suggest scheduling at least two trips into the park to increase your chances. The safaris last about three hours and are held in early morning and late afternoon.

Advance reservations are necessary; demand is high year-round, and the number of visitors is tightly restricted. Book a private six-person Jeep (with driver and guide) at least 60 days in advance. If you can’t get a private Jeep, seats in the open 20-seat “canters” are sometimes available on shorter notice. Your hotel can arrange this: The Oberoi Vanyavilas, for instance, charges about $54 for the Jeep tour and about $27 for the canter.

Tiger sightings are most frequent in the hot months of April, May and June, but from December through March (when the greenery is thicker), the weather is cooler and more pleasant. The park is closed July through September.