By Stephen Brookes • Modernism Magazine • Winter 2010

On the northern edge of Copenhagen, tucked away in a leafy, upscale neighborhood of old houses, old money and even older Lutheran values, sits a plain white house. At first glance, the place seems unremarkable, almost utilitarian; just two one-story buildings connected in an L-shape, opening onto a large garden. Simplicity, color and light reign in the main living area of Finn Juhl’s house. Photo by Anders Sune Berg

Simplicity, color and light reign in the main living area of Finn Juhl’s house. Photo by Anders Sune Berg

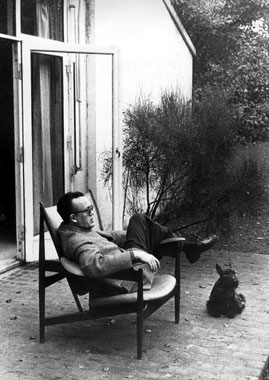

But step inside, and the house becomes anything but ordinary. The open, light-infused rooms are filled with some of the most provocative furniture of the 20th century, from a 1949 Chieftain chair with its imposing, shield-like back, to an iconic Poet couch that gently embraces you in its wings. Paintings from Danish midcentury artists float over chairs and tables formed with such organic lines that they seem almost alive. It’s a house where everything from the traditional Danish carpets to the canvas-colored ceiling comes together in a fresh and satisfying whole. For this is the house that Finn Juhl — the quiet and enigmatic architect who many regard as the father of Danish Modern — designed, built and lived in for more than 40 years. Finn Juhl“I’ve been here so many times, but I still find new details to discover,” says Birgit Lyngbye Pedersen, an art historian who bought and restored the house in 2007 and donated it to the Danish government as a museum, which opened in 2008. “Juhl thought about every detail. He had a vision of making everything for the house, even the cutlery. So the house is unique; it lets you see how Juhl thought about design in his own life, down to the smallest things.”

Finn Juhl“I’ve been here so many times, but I still find new details to discover,” says Birgit Lyngbye Pedersen, an art historian who bought and restored the house in 2007 and donated it to the Danish government as a museum, which opened in 2008. “Juhl thought about every detail. He had a vision of making everything for the house, even the cutlery. So the house is unique; it lets you see how Juhl thought about design in his own life, down to the smallest things.”

Finn Juhl was perhaps the most gifted of Denmark’s extraordinary crop of “Golden Age” designers, a group that came of age in the 1940s and ‘50s and included such luminaries as Arne Jacobsen, Hans Wegner and Børge Mogensen. But by the time he died in 1989, Juhl was virtually forgotten in his homeland — so neglected, in fact, that the Danish government showed little interest in preserving the house after Juhl’s longtime companion, Hanne Wilhelm Hansen, died in 2003. “They thought it was too simple,” says Lyngbye Pedersen. “They didn’t see the point. Most Danes didn’t know about Finn Juhl, and even the Design Museum didn’t collect his work!”

But all that is changing dramatically. With the opening of the house (now part of the Ordrupgaard Museum, which adjoins the property), interest in Juhl has been rising fast. On the international market, prices for the designer’s original pieces are reaching astronomical levels, interest among Asian collectors is almost fanatical and reissues of Juhl’s designs are selling out; the American retailer Design Within Reach began offering several pieces to the U.S. market this past summer. Meanwhile, the Danish Museum of Art and Design has assembled a fine Juhl collection, and one of the designer’s most important projects — the Trusteeship Council Chamber at the United Nations headquarters in New York — is being completely restored.

“Finn Juhl is having a renaissance around the world,” says Preben Pontoppidan, export director of the Danish furniture manufacturer Onecollection, which is licensed to produce Juhl’s designs. “And it’s long overdue.” Juhl’s life was, in fact, a roller coaster of fame and obscurity. Born in 1912, he trained as an architect but soon moved into interior design, where his gifts were quickly recognized. High-profile projects in the 1940’s and 50’s (including the Trusteeship Council Chamber, the Danish ambassador’s residence in Washington, DC and all of SAS Scandinavian Airlines’ air terminals in Europe and Asia) brought him international recognition, and he organized many of the exhibitions — including the “Good Design” exhibit in Chicago in 1951, and another at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1960 — that did much to popularize Danish mid-century design around the world.

Juhl’s life was, in fact, a roller coaster of fame and obscurity. Born in 1912, he trained as an architect but soon moved into interior design, where his gifts were quickly recognized. High-profile projects in the 1940’s and 50’s (including the Trusteeship Council Chamber, the Danish ambassador’s residence in Washington, DC and all of SAS Scandinavian Airlines’ air terminals in Europe and Asia) brought him international recognition, and he organized many of the exhibitions — including the “Good Design” exhibit in Chicago in 1951, and another at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1960 — that did much to popularize Danish mid-century design around the world.

His most important accomplishments, though, were to be in furniture — a field in which he had no training at all. Starting with pieces for his own apartment in the 1930’s, Juhl took a sculptural approach and quickly turned tradition on its head, playing with biomorphic shapes and drawing inspiration from surrealist painters such as Jean Arp and the art of primitive cultures. Teak fascinated him, and he quickly formed a partnership with the gifted cabinetmaker Niels Vodder; together they tested the limits of what the wood could be made to do.

His talent was immediately clear. One of his first designs was the now-iconic “Pelican” chair of 1939, whose swooping arms and exuberant curves anticipated the 1960’s by decades and still look fresh today. Other innovative pieces soon followed, including the delicately flowing NV-45 chair of 1945, the beguiling “Poet” couch from 1941, and perhaps the most imposing chair ever built, the throne-like “Chieftain” of 1949. Painstakingly hand-crafted and produced in miniscule quantities (no more than a dozen of the original Pelicans were made, and fewer than eighty of the Chieftains), they introduced structural innovations — such as “floating” seats and backs — that quickly became hallmarks of the Danish Modern vocabulary.

Juhl began winning awards at Copenhagen’s prestigious Cabinetmakers’ Guild exhibitions. But for all their brilliance, some critics found his designs too radical (one described the Pelican as a “tired walrus”), while many of his colleagues thought he was on the wrong esthetic — or perhaps political — path.

“Finn Juhl was different from the other designers of the time, and they didn’t like him,” says Lyngbye Pedersen, walking through the Juhl house on a sunny, cool morning last summer. “In postwar Denmark, there was a new form of living — the welfare state — and the designers made furniture they called ‘democratic.’ But Juhl was not part of that. His furniture was influenced by free art and prehistoric artifacts. It was not simple. It was hand made, it was expensive, and it was seen as elitist.”

The climate seemed more welcoming in America, and in the 1950’s Juhl shifted toward a more commercial, “common-man” approach, producing a line of mass-produced furniture for the Michigan-based Baker Furniture Inc, and even a refrigerator for General Electric. His fame spread when Edgar Kaufmann Jr., the design director of the Museum of Modern Art, took an interest in Juhl and enthusiastically promoted his work.

But by the 1970’s the Danish Modern wave had largely passed. Juhl fell into obscurity, financial difficulty and relative solitude. Work dried up; he had to lay off most of the employees in his design firm, and even sold pieces from his personal art collection to get by. A retrospective of his work at the Danish Museum of Art and Design in 1982 led to a brief revival of interest, but he never again attained the status he once enjoyed. Finn Juhl passed his last years quietly, dying in May 1989 at the age of seventy-seven.

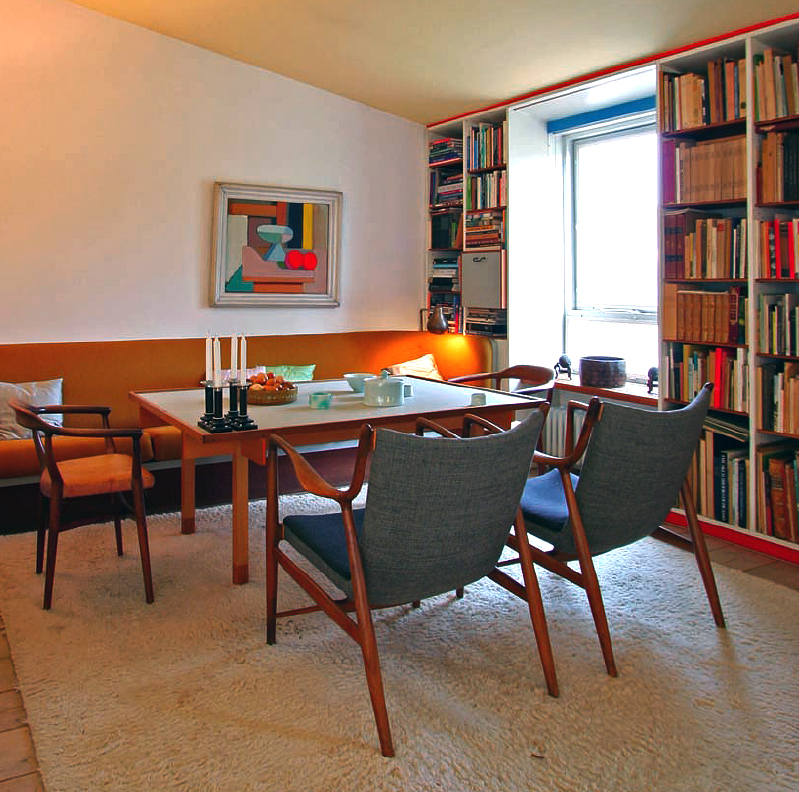

The extraordinary legacy of Juhl’s life, though, lives on in his house. Built in 1942 with money from an inheritance and the simple materials available in wartime Denmark, it’s an early example of open plan layout. Gabled and deceptively plain from the outside, it was designed “from the inside out,” as Lyngbye Pedersen puts it, with clear sight lines from room to room and an airy, light-filled ambiance that makes the house seem much larger than it is. After buying the house, she restored it to the way it was when Juhl was alive, and the result is a fascinating mix of the designer’s most important furniture, numerous prototypes and blueprints, Asian artifacts, and his personal collection of paintings and sculpture by Scandinavian artists including Asger Jorn, Sonja Ferlov Mancoba and Erik Thommesen. Finn Juhl“Juhl was really about three things: furniture, color, and a piece of art,” Lyngbye Pedersen says. The main building, for instance, is arranged into several distinct but connected areas, with art and furniture defining each space. A Poet couch and a Chieftain chair form a sitting area around the traditional fireplace, presided over by a striking portrait of Hanne Wilhelm Hansen by the painter Vilhelm Lundstrom. Low tables display “still lifes” of pieces of sculpture and chinaware, and a pastel Scandinavian rug adds color and leads the eye deeper into the living space, past a 1951 table bench and a Chinese sculpture toward a table on a thick white rug.

Finn Juhl“Juhl was really about three things: furniture, color, and a piece of art,” Lyngbye Pedersen says. The main building, for instance, is arranged into several distinct but connected areas, with art and furniture defining each space. A Poet couch and a Chieftain chair form a sitting area around the traditional fireplace, presided over by a striking portrait of Hanne Wilhelm Hansen by the painter Vilhelm Lundstrom. Low tables display “still lifes” of pieces of sculpture and chinaware, and a pastel Scandinavian rug adds color and leads the eye deeper into the living space, past a 1951 table bench and a Chinese sculpture toward a table on a thick white rug.

This was Juhl’s preferred work space — a corner with an NV-46 chair, lit by a rear window, enclosed with bookcases full of art and architecture books in at least four different languages. But what’s most fascinating about the space is a corkboard covered with Juhl’s visual notes: blueprints for a country house, a poster of a chair exhibit, and an eclectic array of photos ranging from an Egyptian sarcophagus, to the ornate interior of a Renaissance room and the silhouette of an African fisherman.

Another sitting area includes two NV-45 chairs and a rare NV-44 around a table, offset by a 1938 still life by Lundstrom and a prototype lamp of Juhl’s own design. Overhead, tying all three areas together, is a pale yellow ceiling. “Juhl wanted the color to evoke light coming through the roof of a tent,” says Lyngbye Pedersen.

An entryway with a low-slung “Japan” chair (1958) connects the main house to the wing, up a short flight of stairs. The dining room contains a “Judas” table from 1949 (its teak surface is inlaid with 30 pieces of silver), surrounded by six of Juhl’s elegant “Egyptian” chairs from the same year. A short hallway leads to a bedroom simply furnished with a bed, an Ashanti stool and little else, while the master bedroom contains more Juhl gems, including a multicolored cabinet, an elegant shelf system filled with books, and an FJ-48 and bench sofa arranged around a table. The house is attracting growing numbers of visitors — and curiously, the majority are from Japan. “For some of the Japanese, it’s like going to church,” says Lyngebye Pedersen. “They become very quiet; some start crying.” The largest collection of Juhl in the world, in fact, belongs to a professor at Sapporo University named Noritsugu Oda, and other Japanese collectors regularly make pilgrimages to Copenhagen to shop for Juhl originals. And next year, even those who can’t make the trip won’t be left out: the Japanese company Kitani is even building a replica of Juhl’s house outside of Tokyo, exact to the tiniest detail.

The house is attracting growing numbers of visitors — and curiously, the majority are from Japan. “For some of the Japanese, it’s like going to church,” says Lyngebye Pedersen. “They become very quiet; some start crying.” The largest collection of Juhl in the world, in fact, belongs to a professor at Sapporo University named Noritsugu Oda, and other Japanese collectors regularly make pilgrimages to Copenhagen to shop for Juhl originals. And next year, even those who can’t make the trip won’t be left out: the Japanese company Kitani is even building a replica of Juhl’s house outside of Tokyo, exact to the tiniest detail.

“Eighty percent of what we sell of Juhl goes to Japan, but South Korea and Taiwan are also becoming big markets,” says Per Poulsen, the manager of Klassik Moderne Mobelkunst, one of the premiere galleries in Copenhagen. And most of the buyers, he says, have little interest in Jacobsen, Wegner, or any of the other Danish Modern stars. “The people who buy Juhl,” he says, “are not interested in the other designers.”

The interest has pushed prices for Juhl’s work up by about ten percent a year over the past decade, says Poulsen, putting the rare, original pieces out of the range of many collectors. But many of the icons are being reissued, and it’s now possible to get many pieces — including the Pelican chair — for under $5,000.

With the 100th anniversary of Juhl’s birth approaching in 2012, many in Copenhagen are hoping that his work will finally get the recognition it deserves. That may or may not happen, they say, but at least Juhl is no longer fading from view in his own country.

“We honor Finn Juhl now,” says Lyngbye Pedersen, with a sigh. “It’s a pity we didn’t do it when he was alive.”

•••••••••••

VISITING THE JUHL HOUSE

Finn Juhl’s house is part of the Ordrupgaard art museum, and is open weekends and holidays, or by special arrangement; check the website for times. Admission is 90 Danish kroner (about $15). Ordrupgaard is located just over 8 km from the center of Copenhagen and is somewhat inconvenient to get to, but can be reached by train and bus; a car will give you flexibility to explore the surrounding area of Charlottenlund, where several Jacobsen houses are located.

WHERE TO STAY Copenhagen has any number of comfortable hotels, but lovers of Danish Modern may want to take a look at the historic, 260-room Radisson Blu Royal Hotel (Hammerichsgade 1) designed by Arne Jacobsen. The lobby features Jacobsen’s famous “Egg” and “Swan” chairs, but the hotel has been thoroughly updated — it’s very comfortable, but there’s not much mid-century flavor left. Ask if you can see room 606, though, which has been maintained exactly as Jacobsen designed it — except for the gigantic flat screen TV in the middle of the room. Aaarrrgh.

Copenhagen has any number of comfortable hotels, but lovers of Danish Modern may want to take a look at the historic, 260-room Radisson Blu Royal Hotel (Hammerichsgade 1) designed by Arne Jacobsen. The lobby features Jacobsen’s famous “Egg” and “Swan” chairs, but the hotel has been thoroughly updated — it’s very comfortable, but there’s not much mid-century flavor left. Ask if you can see room 606, though, which has been maintained exactly as Jacobsen designed it — except for the gigantic flat screen TV in the middle of the room. Aaarrrgh.

Just as central and infinitely more interesting is the wonderful Hotel Alexandra (H.C. Andersens Boulevard 8), each of whose rooms is decorated with the furniture of a different designer, including Hans Wegner, Borge Mogensen and of course Finn Juhl. The hotel’s owners are passionate about the period, and the Alexandra is a treasure trove of mid-century gems. Not to be missed — at the very least, stop in and admire the lobby.

WHERE TO BUY For upscale art and furniture galleries in Copenhagen, head to Bredgade Street, where you’ll also find the Danish Museum of Art and Design, which has a fine collection of (mostly) chairs from the great designers. When you’re ready to buy, stop in at the friendly, low-key Klassik Moderne Mobelkunst (Bredgade 3), one of the premiere galleries in town for vintage midcentury furniture. Or head over to the funky neighborhood of Nørrebro and explore its many antique shops, where bargains can sometimes be found. One of the best galleries there is Roxy Klassik (Fælledvej 4), which has a vast and fascinating collection of Danish Modern. Fine examples of contemporary design can also be found at Illums Bolighus (Amagertorv 10) and the gift shop of the Dansk Design Center (HC Andersens Boulevard 27).

For upscale art and furniture galleries in Copenhagen, head to Bredgade Street, where you’ll also find the Danish Museum of Art and Design, which has a fine collection of (mostly) chairs from the great designers. When you’re ready to buy, stop in at the friendly, low-key Klassik Moderne Mobelkunst (Bredgade 3), one of the premiere galleries in town for vintage midcentury furniture. Or head over to the funky neighborhood of Nørrebro and explore its many antique shops, where bargains can sometimes be found. One of the best galleries there is Roxy Klassik (Fælledvej 4), which has a vast and fascinating collection of Danish Modern. Fine examples of contemporary design can also be found at Illums Bolighus (Amagertorv 10) and the gift shop of the Dansk Design Center (HC Andersens Boulevard 27).