Fine Art of the Fake Makers

By Stephen Brookes in New York

for Insight Magazine

With its booming market, high profits and low risks, stealing art may be as close to the perfect crime as it is possible to get. But those same conditions are also true of the finer art of forgery, which some investigators say is an even bigger -- and more insidious -- problem than theft. "Art forgery is everywhere, all over the country," says Los Angeles Police Detective William E. Martin, who specializes in art crime. “And it's on the rise."

The problem, of course, is nothing new: Name a reasonably well-known artist, and chances are he’s been faked. Old masters such as Rembrandt and Titian, Impressionists such as Renoir and Monet, modem artists from Dali to still obscure newcomers -- undetected copies of all of them have hung on museum walls and in collectors' homes from Paris to New York to Tokyo.

Forger Thomas Keating / Photo: Rod EbdonForgery of one kind or another is so pervasive, in fact, that Thomas Hoving, who examined more than 125,000 pieces of art in his 16 years as head of the Metropolitan Museum of Ail, once remarked that fully 60 percent of what he looked at was not what it was purported to be.

Phony art is not confined to paintings. Ersatz Greek sculpture, Chinese pottery, African carvings, religious icons from Russia and other phony antiquities have all shown up on the market at one time or another. "The field of pre-Columbian art is rife with fakes," says New York antiquities dealer Ken Bower. "All through the United States and Europe there are people selling them -- maybe more in this field than any other, because it's so esoteric."

One of the best and most prolific forgers ever caught was exposed last year, ironically enough, by one of the very artists he was forging. Vacationing with his family in California in early 1988, the Japanese artist Hiro Yamagata walked into the Carol Lawrence Galleries in Beverly Hills to have a look around. To his surprise, he saw copies of several of his works on display. A yearlong investigation was launched, and last year the Los Angeles police arrested Anthony Gene Tetro; a spokesman for the Los Angeles district attorney's office called him “one of the largest art forgers on the West Coast, if not the United States.”

The high-living Tetro, who was charged with 44 counts of felony forgery and one count of conspiracy to defraud, was as ambitious as he was talented: One of his alleged forgeries, an 8-foot-long Dali called "Lincoln and Dali Vision," would have been worth some $2 million if genuine. And his scope was wide; investigators also tracked down some 250 forgeries attributed to Picasso, Norman Rockwell and others. “Lord knows how many are out there,” says Martin.

For all his skill, Tetro was merely continuing a tradition that has existed for centuries in the art world. Hieronymus Bosch was forged extensively in Spain in the 16th century, and Raphael's work inspired a small army of forgers over the centuries, beginning with the Italian Terenzio da Urbino in the 1620s. Vermeer, Rubens, Picasso and Renoir have all been well and widely forged, and so many fake Corots have flooded the market that dealers joke that the artist “painted 2,000 pictures, 4,000 of which are in the United States.”

While many individual forgeries have become famous, little is known about the forgers themselves. Rarely caught, they tend to live anonymously in the shadows of art history. They range in talent from dealers who forge high-priced signatures onto low-priced paintings to hugely talented craftsmen like the early 19th century master of the Agrafe forgeries, who carved out of ivory more than 100 delicate "Gothic" plaques, so elegantly made that they escaped detection for more than a century.

Some forgers are independent, but most work with accomplices and some are involved in octopuslike organizations that produce, smuggle, distribute and sell the works all over the world. But they tend to be at the bottom rung rather than the top: A forger arrested in Milan in 1975 as part of an international ring told authorities she was paid about $150 for each of the near perfect Kandinskys she turned out, which were later sold for more than $10,000 apiece (bringing to mind Samuel Butler's remark that "any fool can paint a picture, but it takes a wise man to be able to sell it").

Others, while artistically gifted, lack basic horse sense: The Dutch forger Hans van Meegeren faked a Vermeer in the early 1940s and was unwise enough to sell it to Hitler's art-loving marshal, Hermann Goring. Van Meegeren spent the rest of his short life in a Nazi jail cell.

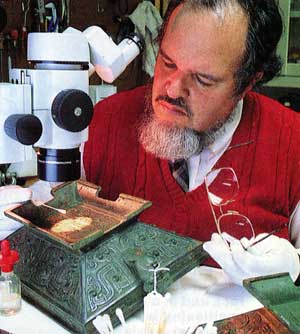

(Inevitably, a market has grown for some of the most notorious forgers. There is a thriving demand for genuine fakes by Elmyr de Hory, who turned out hundreds of phony Matisses, Picassos and Modiglianis that now sell for as much as $15,000. And an auction last December of fakes by Thomas Keating, a well-known British forger who passed off thousands of topnotch works as Renoirs, Monets and Rembrandts, pulled in a cool $268,740.)

But few big works by the old masters and major modem artists are being faked anymore, say forgery watchers: It’s too hard and too expensive to do, and anything high-profile is now thoroughly studied by experts before it goes on the auction block. It is in a much more modest price range that the new forgeries are starting to appear.

“As the market rises, it's not just the top priced works that are forged,” says Virgilia H. Pancoast, director of the authentication service of the International Foundation for Art Research. “There's a big market for forgeries in the $2,000 to $7,000 price range.”

That means smaller works by blue-chip artists, which attract the amateur, investment-minded buyer and are less likely to be examined by an expert. Fakes of American art are abundant right now, as are phony works by Marc Chagall, Joan Miro and the surrealist Salvador Dali. Dali fakes are ubiquitous: Hundreds of millions of dollars' worth have been seized over the past decade, and more show up all the time. Spanish police found about 1,000 fake Dalis in Barcelona last April 6, then seized 700 more in the Canary Islands, many with original certificates of authenticity.

Dali himself, who was notorious for mass-producing works, is partially responsible. But that does not let avaricious buyers, who indulged in a Dali feeding frenzy for much of the past decade (he died last year), off the hook.

"It's not as bad as it was for some years; the Dali market is coming down a bit," says Donna Carlson, director of administration at the Art Dealers Association of America. "But people used to call here endlessly, and I'd tell them: ‘Think about supply and demand. Dali was doing work in massive editions: 1,000 in the United States, 1,000 for the international market, three different kinds of paper and three different kinds of numbering. Are all these things going to keep their value without all this "pushing" atmosphere?’ And people didn't want to hear it. They were desperate to buy, no matter what.”

The entry into the art market of a swarm of first-time buyers, who often have more enthusiasm and money than expertise, has fed the forgery boom. Established galleries run by expert dealers do everything they can to keep out fraudulent works and say they can usually tell if they are offered something fishy.

"We had a guy in here one day who was obviously not legit, and he was trying to sell us a couple of pieces that were clearly fakes," says antiquities dealer Bower, laughing. “So I told him, and he looked indignant and said, ‘Well, da guy dat sold ‘em to me wouldn' dare do dat to me!'’”

With the rising tide of buyers has come a new generation of art galleries ready to sell to them, run not by connoisseurs like Bower but by people eager to cash in on the boom. Catering to the public's appetite for low- and mid-priced works, especially “multiple” pieces such as lithographs, such galleries have sprouted in shopping malls and hotel lobbies all over the country.

Most are aboveboard and reputable, but without the expertise to distinguish a good publisher of prints from a questionable one, they sometimes find themselves the unwitting victims of forgery.

That is apparently what happened to Hanson Galleries of Mill Valley, Calif., in 1984. Hanson had sold a number of prints of a purported Dali work called “The Cosmic Athlete” that it had bought from a print publisher called Magui Publishers Inc. of Beverly Hills. But Magui and its French owner, Pierre Marcand, were apparently selling fakes as fast as they could crank them out: After a long investigation, the Federal Trade Commission sued Marcand last June, accusing him of selling some 22,000 forgeries. (After the FTC brought its case, Hanson Galleries agreed to give refunds to its clients who had bought the prints.)

With technical wizardry such as sophisticated laser scanning now widespread in photomechanical printing, almost anyone with basic printing skills can turn out high-quality forgeries. Simply by photographing a print and transferring it to a lithograph or silkscreen process, forgers can duplicate a print that is virtually indistinguishable from the original - and make thousands of copies.

Publishers target naive dealers or collaborate with dishonest ones. Los Angeles police are currently investigating the case of the Upstairs Gallery, a chain of eight California stores. Police seized 1,685 allegedly fraudulent prints (potential retail value: $15 million) from the chain's Beverly Hills gallery last year and charged the former owner, Lee Sonnier, with five counts of grand theft. Sonnier is also said to have bilked two Japanese collectors out of $872,000 by selling them a number of pieces that were never delivered, including one work, Renoir's "A Young Girl with Daisies," which hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Also under investigation is Larry Groeger, a wholesaler who allegedly supplied Upstairs with the phony prints.

Detecting forgeries from any period is the job of scholars, museum curators and, in tricky cases, skilled technicians armed with sophisticated tools. A curator will always initially examine a piece for obvious errors, stylistic inconsistencies or questionable background.

"Most of the time an art historian knows what's wrong before he turns to the scientists," says Gary Vikan, a curator at the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore who put together a show of the museum's forgeries called "Artful Deception," which is touring the country.

But when scholarship fails, the technical examiners step in. Using microscopes, radiography, chemical analysis and a dating technique called thermal luminescence, they find important clues about the integrity, age and authenticity of a range of objects, from antique sculptures to modem paintings.

The Sackler Gallery's Thomas Chase Brig CabeRadiography is a particularly useful tool; X rays can reveal all kinds of problems, from repairs or alterations to sculptures (like adding a plaster nose) to touching up a canvas or adding a signature.

Vikan describes what they can unveil: "We had one piece which showed St. George slaying the dragon, and it looked as if it were done in the 15th century. The signature read Pettis Venetis, and the art critic Bernard Berenson theorized in 1915 that this was the only known painting by Peter Carpaccio, the long lost son of Vittorio Carpaccio, one of the great early Venetian masters. So it became very, very important, even though it's a crummy painting, as crummy as can be.

“Well, for years it was a sort of pilgrimage for the dedicated art historian,” continues Vikan. “And in the 1970s we x-rayed it, and lo and behold, you could see a ‘Last Supper' underneath it, painted in 16th century style. It was like pulling the last rock out from the basement of the Parthenon and looking down into the trench and seeing a Coke bottle lying there.”

Few phony artworks make it past the technicians' scientific weaponry undetected. “Almost every art fake will be detected, unless it's such a piddling attempt that no one's ever taken the trouble to look at it,” former Metropolitan Museum Director Hoving has said. But note the "almost." It's still possible for a careful, skilled artisan to make a detection-proof piece. "A good forger can make a piece in the same way as the original maker, using the same materials, and it can be very hard to tell," says Thomas Chase, director of the technical lab at the Smithsonian Institution's Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Washington. “There's stuff we have gone back and forth on for decades.”

Some forgers, in fact, will go to extraordinary lengths and will use imaginative tricks in the quest for the perfect fake. For example, when forging the Italian primitives, woodworm holes are added to give a realistic appearance, and collectors' marks and false inscriptions will often be placed on the backs of paintings.

According to Otto Kurz's 1966 book "Fakes," forgers will age a painting by putting it in an oven soon after painting, then cooling it rapidly to crack the paint. Some forgers are said to use a special varnish that has the same effect. And Hoving tells the story of buying a "superb" 15th century religious painting with impeccable documentation and an apparently clean past; only after the museum had paid $75,000 for the piece was it discovered that the complex network of "cracks" all over the surface was actually black paint put on by a brush with only a single hair.

Unmasking phony antiquities can sometimes be even trickier. “Typically you're not dealing with something that's either fake or real,” explains Chase. “Often it's a piece that's very good but has been changed in some way. We had a piece of Chinese bronze horse hardware here once, with a design of elephants with raised trunks, a terrific piece and visually very convincing. But we sent it over for routine radiography, and when we x-rayed it the elephants disappeared. They'd taken a plain but genuine piece and added these elephants in relief and carved out a pattern around them in the original bronze. So it was a nondescript piece that was turned into something really unique. And it was all done probably in the last 40 years.”

Even with technical labs to protect them, museums get taken from time to time: As it was setting up an exhibition of Velazquez last September, the Metropolitan Museum discovered that one of the paintings, a portrait of Infanta Maria Theresa of Spain, was a phony. But private collectors are the real targets of forgers and shady dealers and have to be extremely wary when buying any work of art, particularly prints and other works, such as cast sculptures, made in multiple editions.

“Forgeries have become all-pervasive, and you have to be extremely careful from whom you buy the works and become educated yourself,” warns Pancoast. She advises clients to beware of bargains; to mistrust so-called certificates of authenticity, which are only as good as the paper they are printed on; and to always get complete receipts from dealers.

Reputable dealers (who sometimes inadvertently handle fake or stolen art) will always take a piece back if it turns out to be dubious, but private sellers are sometimes less honorable, especially when the art is offered as a payment of some kind. “People will tell us, ‘I got this Matisse in exchange for some money that a client owed me.’ Whenever I hear that, my antennae go up,” says Pancoast, who examines hundreds of questionable works a year. “Every time that has happened, the piece has turned out to be fraudulent.”

(Insight Magazine, May 7, 1990)