Margaret Leng Tan at the National Gallery of Art

Margaret Leng Tan — the formidable doyenne of the avant-garde piano — has built a career on upending tradition, pushing her instrument into fresh, no-holds-barred sonic worlds. That’s led her into collaborations with some of the most pathbreaking composers in the country, and in a remarkable program on Sunday at the National Gallery of Art, Tan explored some of the innovations that have transformed the piano over the past century — concluding with the world premiere of George Crumb’s “Metamorphoses, Book 1,” a striking new work from a composer who, at 87, shows no sign of slowing down.

Margaret Leng TanTan opened the afternoon with John Cage’s “The Perilous Night,” a 1944 work for “prepared piano” — an instrument created by inserting bits of metal, felt and rubber between the strings, transforming it into a sort of percussion orchestra. It’s a nocturnal work full of shadows and dread, and Tan played it with the restless, aching mystery of a dream. Or, perhaps, of a sleepless night: Cage, who was leaving his wife for the choreographer Merce Cunningham at the time, once said the work arose from “the terror that comes to one when love becomes unhappy.”

Margaret Leng TanTan opened the afternoon with John Cage’s “The Perilous Night,” a 1944 work for “prepared piano” — an instrument created by inserting bits of metal, felt and rubber between the strings, transforming it into a sort of percussion orchestra. It’s a nocturnal work full of shadows and dread, and Tan played it with the restless, aching mystery of a dream. Or, perhaps, of a sleepless night: Cage, who was leaving his wife for the choreographer Merce Cunningham at the time, once said the work arose from “the terror that comes to one when love becomes unhappy.”

Four short and evocative works by the influential composer Henry Cowell — who, in the early 20th Century, brought fists and forearms to the piano — followed, in an exuberantly physical performance by Tan, who wrapped herself over the keyboard to create massive tone clusters, and plunged inside to brush the open strings.

But the highlight of the afternoon was the Crumb premiere, a ten-part piano cycle written for Tan that, like Mussorgsky’s well-known “Pictures at an Exhibition,” transforms a series of artworks into music. Crumb’s always-colorful imagination and palette of sensual techniques were on full display, from the darting, shimmering gestures of Paul Klee’s “The Goldfish,” to the brooding melancholy of van Gogh’s “Wheatfield with Crows” (in which Tan showed her finely-honed cawing skills), to the galloping explosiveness of Kandinsky’s “The Blue Rider.”

But these weren’t mere clever tone-paintings — “Metamorphoses” felt intensely probing and often incantatory, as if conjuring up whole new worlds from the dark, elusive depths of the paintings. Tan played through them as if the fate of the world depended on it, and navigated the battery of instruments (amplified piano, woodblocks, toy piano, wind chimes, red clown nose) with extraordinary focus — winning a sustained standing ovation for herself and for the composer, who was in attendance.

Jupiter String Quartet at the Phillips Collection

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • March 27, 2017

Name yourself after the biggest planet in the solar system, and you’d better be ready with some pretty celestial playing. That — at least at times — was what the Jupiter String Quartet delivered Sunday at the Phillips Collection, in a program that contrasted shimmering works by Mozart and Schumann with Bela Bartok’s driving, intense and darkly explosive Quartet No. 4.The evening opened with Mozart’s Quartet No. 14 in G Major, K. 387, a piece inspired by Haydn’s pathbreaking Op. 33 quartets. It’s an effusive work that lays on the charm from beginning to end, and the Jupiter players gave it a playful, lighthearted reading — with a slight glitch. The closing movement builds to a furious pitch, and in a teasing Haydn-esque touch, Mozart offers what seems to be the triumphant ending — before revealing the real, much quieter close. But the audience burst into such enthusiastic applause at the “false” ending that the players, after waiting for a moment with bows poised, finally just shrugged, smiled and ended the piece right there.

“We rehearsed it that way!” cellist Daniel McDonough said with a laugh, before giving a quick introduction to the mix of folk influences and deep-reaching symmetry in the next work, Bartok’s Quartet No. 4. There’s little discernible playfulness in this vast-feeling quartet — perhaps Bartok’s greatest — and its intricate web of motivic connections, mirror-images and constant reweaving of material is both daunting and fascinating. Opening with a dense and driven opening, it sweeps across an arc of two scherzos and a shadowy middle movement, before dancing itself nearly to death in the full-throttle close. The Jupiter gave it a characterful, illuminating and utterly committed account.

Robert Schumann wrote only three string quartets before giving up the form — not (to these ears, anyway) a terrible tragedy for this most pianistic of composers. But there’s a lot to like in the lyrical quartet in A Major, Op. 41 No. 3, which closed the evening. An engaging work full of Beethoven-ian echoes, it stays in easily fathomable depths and is undeniably lovely. The Jupiter turned in a stellar — planetary? — reading that had the audience on its feet by the end.

Composer Anders Hillborg at the Phillips Collection

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • March 11, 2017

Not to stereotype or anything, but are Swedes the most civilized people on the planet? Thoughtful, open-minded, reasonable to a fault, they may not always set the world on fire, but they contribute more than their fair share of sanity to the global psyche. So perhaps it wasn’t surprising that Thursday night’s smorgasbord of chamber music by Anders Hillborg — part of the Phillips Collection’s “Leading International Composers” series — was both intellectually engaging and warmly approachable, marked by a kind of playful, inclusive modernism that drew on everything from Renaissance music to the driving pulse of rock.  Anders HillborgLess bleeding-edge individualism, in other words, than an embrace of musical community — even down to the Phillips’ seating arrangement, which exchanged the usual strict rows for an intimate, communal semi-circle around the performers. And while the first work of the evening was a rather stately “Opening Fanfare” (written for the Swedish Parliament, hence the stately) played by the Axiom Brass ensemble, the sense of open-minded curiosity that runs through Hillborg’s music quickly emerged.

Anders HillborgLess bleeding-edge individualism, in other words, than an embrace of musical community — even down to the Phillips’ seating arrangement, which exchanged the usual strict rows for an intimate, communal semi-circle around the performers. And while the first work of the evening was a rather stately “Opening Fanfare” (written for the Swedish Parliament, hence the stately) played by the Axiom Brass ensemble, the sense of open-minded curiosity that runs through Hillborg’s music quickly emerged.

The 1998 “Brass Quintet,” for instance, contrasted passages of lazily smeared notes with others of punchy, hard-driving power, while two fine works for string quartet drew intriguingly from composers from Stravinsky to Bach. In the “Kongsgaard Variations” (built around the gorgeous “Arietta” theme from Beethoven’s last piano sonata, Op. 111), Hillborg channeled Beethoven’s dramatic lyricism in a free-flowing meta-style that slipped effortlessly from Renaissance dances to the ultra-modern coda that closed the work. The Calder Quartet turned in an expressive and deeply felt performance, as they did with the seven dark, meditative movements of Hillborg’s 2007 “Heisenberg Miniatures.”

The Kongsgaard Variations was, to these ears, the most revealing and impressive work of the evening. But there were other delights as well. Clarinettist Moran Katz turned in high-powered performances of several short works, from the spare staccato lines of “Tampere Raw” to the darting, birdlike gestures of “The Peacock Moment.” Her reading (with violinist Andrew Bulbrook) of "Primal Blues" was pure fun, as was “Close Up,” with taped tablas providing accompaniment.

But it may have been pianist Amy Yang who stole the show. After joining Katz in “Tampere Raw,” she delivered a jaw-dropping reading of “Corrente della Primavera.” A pianistic tour de force from 2002, the work’s scintillating, white-hot cascades of sound demand both power and exceptional lightness of touch, and Wang brought it off with effortless finesse; a memorable performance of a remarkable work.

Roomful of Teeth and A Far Cry at the National Gallery of Art

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • February 20, 2017

Yodeling, whispering, grunting, even a dollop of Tuvan throat singing — it was all part of Sunday’s never-a-dull-moment performance at the National Gallery of Art by the vocal group Roomful of Teeth and the equally high-octane string ensemble A Far Cry. The two groups showcased new music from rising American composers, from the politically charged work of Ted Hearne to the more ethereal, post-minimalist (and Pulitzer Prize-winning) music of the remarkable Caroline Shaw. Composer Caroline ShawThe Far Cry players opened the afternoon with a transcription of Sergei Prokofiev’s 1917 “Visions Fugitives,” a collection of spare, suggestive miniatures for piano. Prokofiev played them occasionally as biting little encores; here, fleshed out heavily for 18 strings and served up as appetizers, they lost much of their delicate “fugitive” quality, coming off as pleasant and unremarkable as chilled shrimp.

Composer Caroline ShawThe Far Cry players opened the afternoon with a transcription of Sergei Prokofiev’s 1917 “Visions Fugitives,” a collection of spare, suggestive miniatures for piano. Prokofiev played them occasionally as biting little encores; here, fleshed out heavily for 18 strings and served up as appetizers, they lost much of their delicate “fugitive” quality, coming off as pleasant and unremarkable as chilled shrimp.

That may have been the fault of the swampy acoustics of the West Garden Court, which swallows musical detail mercilessly. But the focus sharpened tightly when Roomful of Teeth took the stage for the searing “You Are Not the Guy,” from Hearne’s five-part exploration of racial and cultural identity, “Coloring Book.” Opening in a bouncy, swing-era style, the a cappella work (on a text describing an arrest) darkened and built in power and intensity — a kind of bitter jauntiness in the face of violence.

While much of Hearne’s music is overtly political, his dense, idea-intensive “Law of Mosaics” for strings (which followed in the second half of the program) focused more on pure music, cutting and knitting together sections from other works, deliberately upending any sense of narrative to explore new paths to meaning. Composer Ted HearneHearne’s writing is virtuosic, complex and imaginative — almost to the point of brutality — and A Far Cry played it with fierce dedication. But it was the gentler, more warmly inviting music of Shaw and Rinde Eckert that seemed to most touch the National Gallery audience. Eckert’s yearning “Cesca’s View” from 2009 was built around a kind of melancholy yodeling, and singer Estelí Gomez turned what might have seemed a mere gimmick into a work of sensitivity and grace.

Composer Ted HearneHearne’s writing is virtuosic, complex and imaginative — almost to the point of brutality — and A Far Cry played it with fierce dedication. But it was the gentler, more warmly inviting music of Shaw and Rinde Eckert that seemed to most touch the National Gallery audience. Eckert’s yearning “Cesca’s View” from 2009 was built around a kind of melancholy yodeling, and singer Estelí Gomez turned what might have seemed a mere gimmick into a work of sensitivity and grace.

It was the music of Shaw, though, that was the most compelling of the afternoon. A member of the Teeth ensemble (sadly, not there for the performance), Shaw won the Pulitzer several years ago for her relentlessly inventive “Partita for 8 Voices,” and the singers performed its first movement, the Allemande. Effortlessly weaving together singing, spoken words and any number of vocal effects, the work seems utterly natural and unaffected and true, intellectually vibrant and spiritually almost exalting.

And that was true as well for “Music in Common Time,” a 2014 work for voices and strings that closed the program. Opening with a shimmering D chord as radiant as a sunrise, it seemed to darken and slowly unfold through waves of polytonality, using vocal effects (that Tuvan throat singing, at one point) and deceptively simple writing to create an atmosphere of elusive, luminous mystery that never let go of the heart.

Lise de la Salle at the Phillips Collection

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • January 16, 2017

Fresh off a brutal travel swing (Paris, New York, Bogata and Washington in two days), the gifted — and presumably well-caffeinated — French pianist Lise de la Salle took the stage at the Phillips Collection on Sunday afternoon for a program devoted to the terrors and joys of love. A prodigy who made her concert debut at the age of 9, de la Salle has developed in her 20s into a musical thinker of impressive weight, with charm, imagination and a dazzling technique. And while all that was amply evident Sunday, it seemed to take de la Salle a while to settle into the emotional depth of the music. Opening with three transcriptions by Liszt of love songs by Schumann and Wagner, de la Salle turned in big, sweeping readings that, for all their virtuosity, felt rather dry-eyed — declamatory rather than seductive, lush but rarely rapturous, detailed but lacking in tenderness or mystery. Maybe it was just understandable exhaustion. But as love goes, it all felt a bit clinical.

A prodigy who made her concert debut at the age of 9, de la Salle has developed in her 20s into a musical thinker of impressive weight, with charm, imagination and a dazzling technique. And while all that was amply evident Sunday, it seemed to take de la Salle a while to settle into the emotional depth of the music. Opening with three transcriptions by Liszt of love songs by Schumann and Wagner, de la Salle turned in big, sweeping readings that, for all their virtuosity, felt rather dry-eyed — declamatory rather than seductive, lush but rarely rapturous, detailed but lacking in tenderness or mystery. Maybe it was just understandable exhaustion. But as love goes, it all felt a bit clinical.

Things warmed up noticeably in Schumann’s “Fantasie” in C, Op. 17, which opens with an impassioned love letter to his soon-to-be-wife, Clara. De la Salle seemed, for the first time that afternoon, to be playing from the heart, bringing emotional subtlety and personality to the work.

But de la Salle’s most impressive gifts — for narrative, dramatic structure and forceful, sharp-edged playing — may have been best revealed in the closing work of the program, Prokofiev’s “10 Pieces From Romeo and Juliet,” Op. 75. A reworking of the composer’s 1935 ballet, it traces the Shakespearean story from lighthearted opening to tragic end, and de la Salle gave it a psychologically astute, often mesmerizing reading. Richly colored, imaginative and emotionally searing (the dark ending tore mercilessly at the heart), it was a striking performance that won de la Salle a standing ovation.

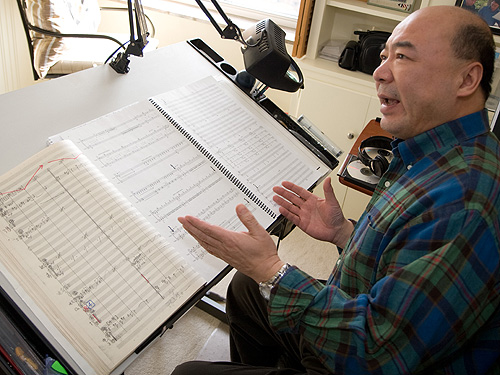

Composer Zhou Long at The Phillips Collection

Zhou was in town with Music From China, the ensemble he founded in New York in 1984, as part of the Phillips’s always interesting Leading International Composers series. Zhou has earned growing praise for his large-scale works (the opera “Madame White Snake” won him the Pulitzer Prize in 2011), but the chamber works on the program — played largely on traditional Chinese instruments — were no less dazzling in their delicate intensity and epitomized Zhou’s effortless transcending of cultural boundaries.

Zhou was in town with Music From China, the ensemble he founded in New York in 1984, as part of the Phillips’s always interesting Leading International Composers series. Zhou has earned growing praise for his large-scale works (the opera “Madame White Snake” won him the Pulitzer Prize in 2011), but the chamber works on the program — played largely on traditional Chinese instruments — were no less dazzling in their delicate intensity and epitomized Zhou’s effortless transcending of cultural boundaries.Take, for instance, “Impression of Wintersweet,” which opened the program. It’s built around a traditional 4th-century folk melody, played on xiao (an end-blown bamboo flute) and zheng (a kind of zither). But floating quietly behind the duet was a modern “shadow” of the music, played on percussion, that made the music seem to echo between the centuries.

Zhou is a gifted musical colorist with deep roots in the natural world, as was clear in the playful dissonances and quick-changing rhythms of “Valley Stream” from 1983 and in the deft sound-painting of “Three Chinese Folk Songs” and “Taiping Drum.” “Mount a Long Wind” was an exuberant, fiery tour de force with an almost orchestral palette of sound, and the natural lyricism that runs through so much of Zhou’s music was nowhere more moving than in “Green,” a sort of vocalise for bamboo flute and pipa.

But Zhou’s most interesting and probing ideas seemed to emerge in “Heng (Eternity),” for small ensemble. Elusive and wonderfully shape-shifting, it seemed to always be on the verge of pulling the rug out from under itself — an endlessly intriguing work from a composer who is starting to win the acclaim he richly deserves.

In Wales, It's Back to the Old Family Castle

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • September 29, 2016

It’s early on a crisp, clear morning in July — hours before the first tourists will start to arrive — and Dame Emily Naper is walking through the ruins of her old ancestral castle, thinking about butterflies.

“Manorbier is a magical place, the most romantic castle in the world,” she says of this picturesque 12th Century manor on the rugged coast of Wales, which she inherited three years ago. “I collected butterflies and wildflowers here as a girl, and I want to keep it natural. It’s better for the imagination, don’t you think?”

On this gorgeous morning, with the sun turning the high stone battlements to gold over our heads, it’s impossible to disagree. There may be, in fact, few medieval ruins in the world as unspoiled and naturally beautiful as Manorbier Castle. Set on a remote ridge over a small bay, this once-lavish estate has weathered the past nine centuries with remarkable grace, and everywhere you turn are the ruins of a vanished world — a kitchen fireplace large enough to roast an ox, limestone floors worn smooth with time, narrow staircases spiraling up through battle-scarred towers.

It feels forgotten and almost dreamlike here, as if we’d stumbled into a place undisturbed for centuries. And when Naper pushes open a postern door to the outside, a landscape appears that nearly takes my breath away: meadows of wildflowers sweeping down to the glittering sea, with the cliffs of the rugged Welsh coastline stretching off into the distance.

“I may never leave,” I tell her, a little intoxicated by the view. “Well,” she says with a playful grin, “if you’re interested in investing ….”

But much as we’d like to, my wife and I haven’t come to this idyllic spot — the last privately-owned medieval castle in Wales — to buy in. In fact, we’re here on a kind of pilgrimage. Last year, I’d come across a long-forgotten genealogy of my mother’s family, which traced our ancestors back to a Norman knight named Odo. A leader of William the Conqueror’s invasion of Wales, Odo had been rewarded in 1093 with huge estates along the Welsh coast, and made a Baron. He took the name “de Barri” from a nearby island, built a castle, and settled down to start a family.

In fact, we’re here on a kind of pilgrimage. Last year, I’d come across a long-forgotten genealogy of my mother’s family, which traced our ancestors back to a Norman knight named Odo. A leader of William the Conqueror’s invasion of Wales, Odo had been rewarded in 1093 with huge estates along the Welsh coast, and made a Baron. He took the name “de Barri” from a nearby island, built a castle, and settled down to start a family.

And that all led, some 900 years later, to this trip. For Odo de Barri, it turned out, was not only the builder of Manorbier Castle — he was also my 26th great-grandfather, and the man who gave my mother’s family, the Barrys, its name.

So, like anyone who discovers a castle in the family, we decided to go and have a look. And after tracking down the charming Dame Emily, who promptly offered to come meet us at Manorbier (from her, ahem, other castle, in Ireland), we flew to London at the end of June and caught the five-hour train to Tenby, a seaside town in the Welsh county of Pembrokeshire, just a few miles down the road.

To be honest, we’d never really paid much attention to Wales before this. Tucked between England and Ireland, the whole country is only about the size of Massachusetts, and doesn’t have much in the way of famous attractions. As far as we knew, Wales was equal parts coal mines, Dylan Thomas, and possibly sheep.

But as we waited for Naper to arrive in Pembrokeshire, we discovered that this southwest corner of Wales was both steeped in history and spectacularly beautiful. Surrounded on three sides by the ocean, it has what may be the most dramatic coastline in Britain, and if you’re ambitious enough you can hike its entire 186-mile length along the protected Pembrokeshire Coastal Path. Not being that ambitious, we tackled a significantly shorter stretch, but even that was unforgettable; it’s not for nothing that National Geographic ranks this as the second-best such path in the world.

And if hiking’s not your thing, you can go whale-watching off the coast, inspect rare puffins in the wildlife preserves, or try the local sport of “coasteering,” which we were told (before we ran away, whimpering) involves helmets, wetsuits, and “flinging yourself from towering vertical rock faces."

Tenby itself, meanwhile, turned out to be a pleasantly old-fashioned seaside resort with cobblestone streets and pastel-colored Victorian houses, perched almost jauntily on a cliff over the ocean. With great restaurants and any number of sun-drenched cafes to choose from, we could have happily lazed away our week there doing pretty much nothing at all.

But we’d had the good fortune to meet one of the most intriguing people in Pembrokeshire. Marc Treanor, a fifty-something artist, philosopher and genial free spirit, makes a living carving vast geometric “sand circles” into the beaches of Wales. Intricate and immense — they can run fifty yards across— and not unlike crop circles, his creations can only be fully seen from above. And Tenby, with its high cliffside promenades looking down over flat sandy beaches, makes a near-perfect canvas. So we met up with Treanor on Tenby’s North Beach one gray afternoon for a private workshop, and for the next few hours — using only long wooden sticks, a ball of string, and a daunting amount of concentration — we drew a series of long, intersecting curves in the sand, darkening sections here and there with metal rakes. From ground level, it just looked like a lot of scratches. But we noticed that a crowd had gathered on the cliff above us, and when we finally put down our rakes and climbed up to join them, we saw what we’d created: a gigantic, mandala-like “flower of life” that seemed to blossom out of the sand. It felt like we had tattooed the world.

So we met up with Treanor on Tenby’s North Beach one gray afternoon for a private workshop, and for the next few hours — using only long wooden sticks, a ball of string, and a daunting amount of concentration — we drew a series of long, intersecting curves in the sand, darkening sections here and there with metal rakes. From ground level, it just looked like a lot of scratches. But we noticed that a crowd had gathered on the cliff above us, and when we finally put down our rakes and climbed up to join them, we saw what we’d created: a gigantic, mandala-like “flower of life” that seemed to blossom out of the sand. It felt like we had tattooed the world.

“Ah, but now comes the best part,” Treanor said, pointing out at the tide. “By tomorrow, it will have all washed away. It’s ephemeral. And that’s what makes it beautiful.”

That philosophy might, in a way, also apply to Wales’ main attraction: its ancient castles. There are some 600 of them scattered around the country — more than anywhere else in Europe — ranging from rudimentary earthworks to restored manor houses, and most have fallen into a state of picturesque, even poetic, decay. The remnants of Cilgerran Castle, for instance, are so mercilessly poignant that they were a tourist attraction way back in the 18th Century, and there are few sights as sigh-inducing as the elegant ruins of Carew Castle at sunset.

That poetry, though, tends to evaporate when you’re being guided around in a herd, and Pembrokeshire’s most famous castles — Carew, the historic fortress of Pembroke, the elegantly-preserved Picton and a few others — are fixtures on the well-worn tourist route, with hordes of visitors trudging through every day.

Those castles are still worth seeing, but it’s far more rewarding to get off the beaten track. So the next morning we navigated Pembrokeshire’s narrow lanes to a tiny, remote village by the sea, walked down a stately drive, crossed over a grassy, long-dry moat and found ourselves, quite alone, at the door of Manorbier Castle.

“Nobody knows we’re here!” Naper cheerfully greeted us, as she bustled around with her small staff, getting the place ready to open for the day.  Given its beauty and spectacular setting, it’s odd that Manorbier has remained so overlooked. First built by Odo de Barri in earth and timber, the castle was rebuilt in stone by his son William around 1140 and expanded over the next two hundred years, to include a chapel, guard towers and barns within the high curtain walls, all of which remain. But after passing out of Barry hands in the 14th Century, Manorbier gradually declined, and by 1630 was being described as “ruynous.”

Given its beauty and spectacular setting, it’s odd that Manorbier has remained so overlooked. First built by Odo de Barri in earth and timber, the castle was rebuilt in stone by his son William around 1140 and expanded over the next two hundred years, to include a chapel, guard towers and barns within the high curtain walls, all of which remain. But after passing out of Barry hands in the 14th Century, Manorbier gradually declined, and by 1630 was being described as “ruynous.”

And little has changed since.

“It was like the Titanic when I first came here,” Naper told us, over a cup of tea in the courtyard. She’s made necessary repairs, cleaned up the gardens and and developed ways to boost income (castles are insatiable money pits), from opening a small cafe, to hosting weddings in the chapel, to presenting evenings of opera in the open courtyard. But she has little use for the guided tours and elaborate displays of her competitors, and Manorbier remains refreshingly low-key. Visitors can roam the castle freely on their own, soaking up the atmosphere and letting their imaginations be their guide.

And Manorbier has one more feature that, we were about to find, makes it perhaps the most distinctive anywhere. There’s an unobtrusive 19th Century cottage inside the castle walls which Naper rents it out by the week, and it’s usually booked years in advance. But the cottage had come open just as we arrived, and Naper, to our delight, told us we could take it for the night. We would have the entire castle to ourselves, she said, putting the key into my hand.

So after a stroll on the nearby beach and dinner in the village, we walked back to Manorbier in the summer twilight to reclaim, if only briefly, the long-lost Barry castle. And for the next few hours, as the shadows deepened around us, we wandered through the silent ruins alone. We sat in the huge, crumbling hall where my ancestors had lived their lives, lingered in the chapel where they had prayed, and climbed an ancient tower to look, as they would have, out over the darkening sea.

It was, as Naper had said, magical. And when the stars finally came out over the crenellated walls, we said goodnight to the ghosts we’d conjured up, took a last look around, and went into the cottage to dream.

IF YOU GO:

GETTING THERE

Pembrokeshire is easy to get to from either England or Ireland, and Tenby is a perfect base for exploring. We took a circular route, flying into London and taking the five-hour train to Tenby the next day. We returned home via Dublin, taking the ferry from Pembroke to the Irish port of Rosslare, then a train north to the capital. Makes for a great trip.

London: The Arts Club

40 Dover Street, Mayfair London W1S 4NP

020 7499 8581

www.theartsclub.co.uk/ It's worth going to London just to stay at The Arts Club, in the heart of Mayfair Elegant, luxurious, and incredibly hip, this iconic club has been around since 1863, and a top-to-bottom renovation several years ago has made it perhaps the best hotel in town. Drinks in the courtyard and dinner at the superb Brasserie made for an unforgettable stay.

It's worth going to London just to stay at The Arts Club, in the heart of Mayfair Elegant, luxurious, and incredibly hip, this iconic club has been around since 1863, and a top-to-bottom renovation several years ago has made it perhaps the best hotel in town. Drinks in the courtyard and dinner at the superb Brasserie made for an unforgettable stay.

Dublin: The Westbury Hotel

Grafton Street, Dublin, Ireland

353 1 679 1122

www.doylecollection.com/hotels/the-westbury-hotel It was our first trip to Dublin, and the gorgeous, centrally-located Westbury Hotel, just off lively Grafton Street, was a perfect base for exploring the city.

It was our first trip to Dublin, and the gorgeous, centrally-located Westbury Hotel, just off lively Grafton Street, was a perfect base for exploring the city.

Both elegant and friendly, with a superb new restaurant called Wilde, the Westbury left little to be desired. Highly recommended.

IN WALES

The historic Welsh seaside resort of Tenby offers everything from surfing to whale-watching, or just strolling its ancient cobblestone lanes. Don’t expect fancy; Tenby is a relaxed, down-to-earth place with plenty of comfortable family hotels and great seafood. Great for families.

The Park Hotel

North Cliff, Tenby

South Pembrokeshire, SA70 8AT

+44 018 34 84 2480

www.parkhoteltenby.com/ We loved the old-fashioned Park Hotel, with its unbeatable views of Tenby. Set on a verdant cliff about a ten-minute walk from the town center, it’s comfortable and loaded with personality. Rooms run $160 to $250 in season.

We loved the old-fashioned Park Hotel, with its unbeatable views of Tenby. Set on a verdant cliff about a ten-minute walk from the town center, it’s comfortable and loaded with personality. Rooms run $160 to $250 in season.

Plantagenet House Restaurant

Quay Hill, Tudor Square, Tenby SA70 7BX

+44 01834 84 23 50

www.plantagenettenby.co.uk/

Housed in the oldest building in Tenby (parts of it date back to the 10th Century) Plantagenet House was a real find, with world-class cuisine and an old-world atmosphere. The imaginative, locally-sourced entrees run $26 to $50, with most starters about $10.

Caffè Vista

3 Crackwell Street, Tenby SA70 7HA

+44 1834 84 96 36

For coffee or light lunch with a great view over North Beach, this awesomely hip cafe is the place to hang out. Try the amazing cappuccino (about $3) and Greek lunch dishes ($10 to $16).

PLACES TO SEE

Pembrokshire’s medieval castles offer a compelling look into its fascinating, turbulent and romantic past. There are about a dozen of them within an hour of Tenby worth seeing, including:

Manorbier Castle

Manorbier, Tenby SA70 7SY

+44 1834 87 00 81

www.manorbiercastle.co.uk/ Manorbier Castle isn’t the biggest castle in Wales, but it may be the most captivating. Open daily from 10 am to 5 pm, March through October ($7.50 admission). Plan to spend a day there; after exploring the ruins, you can stroll down to the beach for a picnic, or hike the magnificent coastline. The 12th Century church of St. James and a neolithic stone tomb called the King’s Quoit are also within easy walking distance.

Manorbier Castle isn’t the biggest castle in Wales, but it may be the most captivating. Open daily from 10 am to 5 pm, March through October ($7.50 admission). Plan to spend a day there; after exploring the ruins, you can stroll down to the beach for a picnic, or hike the magnificent coastline. The 12th Century church of St. James and a neolithic stone tomb called the King’s Quoit are also within easy walking distance.

For a unique experience, stay in Manorbier’s fully-equipped cottage, which gives you the entire castle to yourself in the evening. It sleeps 12 and goes for $4,160 per week in the summer, and about half that in winter. But book early — it’s popular.

Pembroke Castle

Pembroke, Pembrokeshire, SA71 4LA

+44 01646 68 15 10

www.pembroke-castle.co.uk/pages/home

The most important castle in Pembrokeshire, Pembroke Castle is open year-round (summer hours 9:30 am to 5:30 pm, adult admission £6.60) and is heavy on exhibits, special events and re-enactments of medieval life. A great place to bring kids.

Picton Castle

Haverfordwest, Pembrokeshire SA62 4AS

+44 01437 75 13 26

www.pictoncastle.co.uk/

Open from mid-March through October (10 am to 5 pm, admission $12.50), the 12th Century Picton Castle is wonderfully well-preserved, and furnished with 18th Century antiques. It’s also home to one of the most beautiful gardens in Wales, a fine restaurant, and — awesomely — a world-class collection of antique lawnmowers.

Carew Castle

Carew, Tenby SA70 8SL

+44 1646 65 17 82

www.carewcastle.com

The 13th Century Carew Castle is a stunner, with a rich history and elegant setting — it’s built on the site of an Iron Age fort — and should be on everyone’s castle list. Open March to October, admission $7.00.

NON-CASTLE-Y THINGS TO DO

If you’re castled-out (it happens), hike at least some of the 186-mile Pembrokeshire Coastal Path for some fresh air and the most stunning views in Britain. Or drop by Tenby’s harbor to find a huge range of fun, affordable boat trips, including deep sea fishing, whale watching, and outings to nearby islands. The picturesque Cistercian monastery on Caldey Island is a popular destination for day-trippers. For a more offbeat experience, spend an afternoon with the artist Marc Treanor creating a mysterious “sand circle” on one of Pembrokeshire’s beaches. He’s great fun to hang out with, and offers private workshops tailored to your group. Contact him via his website, www.sandcircles.co.uk.

For a more offbeat experience, spend an afternoon with the artist Marc Treanor creating a mysterious “sand circle” on one of Pembrokeshire’s beaches. He’s great fun to hang out with, and offers private workshops tailored to your group. Contact him via his website, www.sandcircles.co.uk.

(This story also ran in The Philadephia Inquirer, the Austin American-Statesman, and several other papers.)