Battling the Tomb Raiders of Latin America

By Stephen Brookes

for Insight Magazine Acting on a tip from police last year, archaeologist Walter Alva was led to an ancient burial ground at Huaca Rajada in Peru's Sipan Valley, where excavations of a looted site revealed the tomb of a warrior priest about 1,500 years old. Inside were some of the most extraordinary artifacts yet found in the Western Hemisphere: beautifully crafted lapidary jewelry, a unique copper headdress and a figure made of turquoise and gold which may be the finest single piece of pre-Columbian jewelry ever found.

Acting on a tip from police last year, archaeologist Walter Alva was led to an ancient burial ground at Huaca Rajada in Peru's Sipan Valley, where excavations of a looted site revealed the tomb of a warrior priest about 1,500 years old. Inside were some of the most extraordinary artifacts yet found in the Western Hemisphere: beautifully crafted lapidary jewelry, a unique copper headdress and a figure made of turquoise and gold which may be the finest single piece of pre-Columbian jewelry ever found.

"There's never been an archaeological find to match the quantity and quality of gold dug up at Huaca Rajada," says Christopher B. Donnan, who worked with Alva at the site. "It's phenomenal."

While it’s considered one of the great archaeological finds of the century, the tomb might never have been discovered had it not been for a police raid on a gang of looters – or huaqueros, as they are known – that left one of them dead.

"The police have always been aware that there were looters actively working the valley area. But it was only after they went into one of the looters' homes and found gold pieces that I was notified," said Alva, director of the Bruning Archaeological Museum in nearby Lambayeque.

The find at Sipan has focused renewed attention on the growing problem of looting and the subsequent loss of the archaeological resources. It’s also reopened the debate over ownership and protection of ancient artifacts, pitting the interests and rights of dealers and collectors against those of the scientists and governments.

The issue is complex, with interlocking and sometimes murky questions of patrimony, ownership, protection and preservation, and any solution to the problem will be complex. But without determined action, say archaeologists, Latin America's heritage could be lost within a matter of years.

The looting itself, whether by peasants digging up the odd pot or by well-organized and well-financed teams of professionals, is widespread around the world and has become particularly acute in Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, Costa Rica, Bolivia, Ecuador, Peru and Chile. It’s not a new problem -- archaeologists at the Maya Tikal site in Guatemala have found evidence of looting from 1,000 years ago -- but its pace has picked up rapidly since the early 1970s.

"The traffic in cultural goods grows every day," says Alberto Tamayo Barrios, head of the Patrimony Office of Peru's Foreign Ministry.

Nevertheless, government officials are hard-pressed to stem the tide. With the pre-Columbian artifacts market so strong, they say, and the problems of policing the illegal traffic so extensive, looting and smuggling take place almost openly in many countries.

Tomb at Huaca RajadaAs far as archaeologists are concerned, the looting represents destruction of an irreplaceable resource. As looters dig random tunnels and trenches into tombs, delicate objects are often smashed. The destruction is, in many cases, extensive. Poking into graves with long metal sticks, digging indiscriminately with pickaxes, sometimes even using dynamite, local looters destroy as much as they come away with.

"I shudder to think of all the things that just get stomped on," says George E. Stuart, an archaeologist with the National Geographic Society.

Just as important as the destruction of objects, however, is the loss of the context in which they are discovered. Those that are retrieved intact soon disappear into private collections in the United States, Japan and Europe without being cataloged or studied. Analysis of the exact location and arrangement of goods found in tombs and religious sites, especially in relation to skeletal remains and architectural elements, can yield important clues to their social, religious and demographic significance. But when artifacts are unearthed and sent abroad, the archaeological record is erased.

"When something enters a collection, it's already lost half its story," says Ian Graham, a Maya researcher at Harvard University's Peabody Museum.

While the looting is undeniably fueled by the strong market in the United States and Europe, dealers and collectors are quick to deny charges that they are ultimately, if indirectly, responsible for the problem. None condones looting, yet most insist that the objects are better-treated and more carefully preserved in collections in the developed world than they would be in the countries of origin.

"When an American collector purchases Maya pottery, you can be very sure he takes good care of it," says Douglas C. Ewing, president of the American Association of Dealers in Ancient, Oriental and Primitive Art. "And when it is seized by a Mexican authority and given to a museum, it is not taken care of."

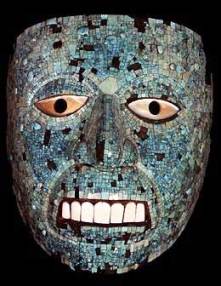

Aztec maskTo a certain degree, that is true. A 1983 study by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization found that Peru's museums were not adequately protecting many artifacts, exposing textiles, grave goods and preserved remains to the predations of insects, rodents, humidity and mold.

Most U.S. museums provide better care than Latin American museums can afford, but "the old excuse that other nations are not taking care of the things, therefore they should be given to American museums, is a red herring," says Robert Sharer, an archaeologist at the University of Pennsylvania. "Objects in any collection are going to be subject to deterioration over time, and that's true in a private collection."

Dealers also reject the argument that Latin American governments have a legitimate claim of patrimony over artifacts dating back many centuries.

"The people in the seats of power in Mexico City have no ancestral pretensions to the Maya at all, and would be insulted by the suggestion," says Ewing. "The predominant culture, which makes such a strong effort to reclaim Maya culture, at the same time tries to suppress the Maya themselves. And it's even worse in South America.”

That doesn’t let collectors in the United States off the hook, archaeologists say. Latin American governments are sensitive to the issue, and charges that U.S. collectors are exploiting area poverty are deeply felt. "I can assure you that the ill will we gain from collecting their artifacts is substantial," says David A. Freidel, a professor at Southern Methodist University.

Much of the looting is done by local people, many of whom are continuing a tradition started by their fathers or grandfathers. Many of them live at a bare subsistence level, and digging up artifacts and selling them to tourists provides them an important, even irresistible, source of income. Even some archaeologists find it hard to blame them. "If I were trying to feed a family and found something in a mound I could sell for three months' income, I'd go for it," admits one.

A good deal of the tomb robbing, however, is done by professional or semiprofessional bands. operating with varying degrees of collusion from government officials. For example, at the Rio Azul site in Guatemala, discovered in 1984, archaeologists led by Richard Adams of the University of Texas at San Antonio found hundreds of trenches dug randomly into the sides of pyramid mounds, some of them almost 60 feet deep. "To move that much earth," Adams estimated, "there must have been 40 men at work for about eight months."

Teams that size, says Charles Koczka, a former U.S. Customs agent who chased art smugglers for 14 years, are often organized by Latin American collectors who are digging primarily for their own collections but also to find pieces they can sell to U.S. or European collectors. Once a suitable object is uncovered, Koczka says, the collector would call a dealer in the United States, who would come down to inspect it. Some observers, such as Karl E. Meyer in his 1977 book, "The Plundered Past," have suggested that U.S. collectors and dealers were directly involved in raids on sites. But others insist that that kind of involvement is long over. "It's now probably 15 or more years since any Americans were actually involved in the field, because those people have graduated," says Harvard's Graham. "They've become owners of galleries."

Some observers, such as Karl E. Meyer in his 1977 book, "The Plundered Past," have suggested that U.S. collectors and dealers were directly involved in raids on sites. But others insist that that kind of involvement is long over. "It's now probably 15 or more years since any Americans were actually involved in the field, because those people have graduated," says Harvard's Graham. "They've become owners of galleries."

Other archeologists, notably Freidel, have pointed to evidence of links between drug smugglers and tomb looters - a relationship that U.S. Customs agents agree is likely, though unproved. Freidel also insists there are "excellent reasons to believe that insurgents in the Maya area are involved in the artifact trade to buy arms."

The best-documented example of that, he says, was the looting and burning of facilities at the Tikal project in Guatemala, where "paramilitary troops came in, burned records and looted artifacts out of the museum."

Such incidents are undoubtedly to be expected in areas of political instability, although Graham says some of the guerrilla bands are "very idealistic, conservation-minded people" who have prevented looting in some sites. Many observers worry more about corruption among government officials. "Take a farmer who accidentally comes across a tomb and finds some things," says Kazak. "If he takes it to the authorities, will it make its way eventually to the national museum? I just don't know."

Sharer of the University of Pennsylvania shares similar concerns. "We were involved in a program in the early 1970s in Guatemala," he says, "and all the materials we found at this excavation - jade, artifacts, polychrome pottery - were turned over to the government.”

Those artifacts, however, never made it to the national museum. Stored in a government warehouse in the town, they were looted almost immediately. “I'm convinced it was organized and financed from the outside," he says. "The guard was probably paid to look the other way, and particular objects were stolen. It was a highly selective operation."

The problem of corruption appears to be widespread. “What export does occur takes place with the full blessing of the government,” says Ewing. "Not the president, of course. But the local police and customs are the ones getting rich off this." Some archaeologists agree, guardedly. "Some artifacts are so large that they must involve cooperation at some level in the officialdom, but we don't know what those levels might be,” says Freidel.

Low-level corruption aside, archaeologists agree that stopping international trade in artifacts depends on developing a body of effective international law, but so far, only a confusing patchwork of legislation has been implemented.

"The legal morass is incredible," says National Geographic's Stuart. "You're dealing with the laws of several different countries and with international law, and with the laws of the United States as well as the costs of pursuing it:”

All Central American countries have legislation barring excavations without official permission, and some, like Peru, make the state the sole owner of whatever is found. Guatemala, Mexico and Peru also have agreements with the United States to aid in the recovery and return of stolen artifacts. Congress in 1972 prohibited the import of monumental sculpture, murals and certain other goods without a permit from the exporting country.

The United States adopted implementing legislation in 1982 for the UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property. The broad international agreement is designed to allow free exchange in the legal market while blocking the sale of stolen artifacts. But under pressure from art dealers, a compromise was written into the U.S. legislation that says it will be enforced only if similar enforcement is undertaken in other art-importing countries. It has therefore only worked in extremely narrow cases, and then only for limited periods. Its effect on limiting artifact trade has been minimal, observers say.

Any effective solution to the looting problem is going to involve a combination of legislation, effective enforcement. education and economic development in the exporting countries, archaeologists say. Among importing nations, cutting demand is considered key. "It's sort of like Prohibition," says one archaeologist. "If the demand is there, you can't really expect law enforcement to solve the problem.”

One of the most critical steps has already been taken: a crackdown by the Internal Revenue Service on collectors who buy artifacts as a tax dodge.

"The tax deductions which people got for donating their pieces to museums were usually appraised in the most slipshod and crooked manner," says Graham, explaining that appraisers and dealers would connive to inflate the value of artifacts their customers planned to donate and use as deductions. One group, based in the Bahamas, invited investors to buy artifacts, own them on paper for a short time and then donate them for a tax break - all without ever seeing a single item. The practice was widespread until 1986, when Internal Revenue began to examine appraisals much more closely.

Genuine collectors are becoming more sensitive to the problem of looting, say archaeologists, and dealers are becoming more wary about what they buy. But as the U.S. market becomes more restrictive, it is likely that the markets elsewhere will pick up the slack.

"The pre-Columbian business in this country has almost dried up," says Ewing. "But it's absolutely booming in Europe.” An effective international effort to restrict trade in artifacts seems necessary, but elusive.

"Just the scale -- the number of people digging, the money behind the looting far outweighs what archaeologists can raise for research, so it's kind of a losing battle," says Sharer. "Unless something is done in the next generation, there's going to be nothing left to dig."