First Ascent: Ozaki Summits Burma's Highest Peak

By Stephen Brookes in Rangoon

for Asia Times

Japanese alpinist Takashi Ozaki has conquered some of the highest and most challenging mountains in the Himalayas -- peaks like Kanchenjunga, Lhotse and Everest's forbidding North Face. His latest triumph was the first ascent of Myanmar's remote Hkakabo Razi -- which, at 5,881 meters, is considerably lower than the 8,000-meter peaks he usually aims for.

But Ozaki has only one thing to say about Hkakabo Razi: It was so hard, he never wants to do it again.

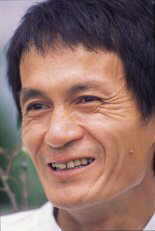

Takashi Ozaki"We are always looking for the more difficult climb -- this is the spirit of alpinism," he said in an interview in Yangon after the climb, looking tired and wan. "But we had to fight the weather constantly. I can say absolutely that Hkakabo Razi is one of the most difficult and dangerous mountains in the world. I was never scared before, like this time -- I wanted to always run away from this mountain."

Like all first ascents, the conquest of Hkakabo Razi -- whose summit was reached by Ozaki and the Myanmar climber Niyma Gyaltsen on September 15 -- was never assured. One of the most significant unclimbed peaks in the world, it was off-limits for decades because of fighting between the government and separatist Kachin rebels.

In fact, little was known about it even as recently as three years ago, when Ozaki and his French wife (and climbing partner) Frederique Gely-Ozaki first broached the subject.

"I was interested in migration patterns of elephants between India and Myanmar," said Gely-Ozaki, who has written widely on Asian wildlife. "And when I talked with the Myanmar officials, the subject of Hkakabo Razi came up. They said they were signing a cease-fire with the rebels, and that it was time to open up the area."

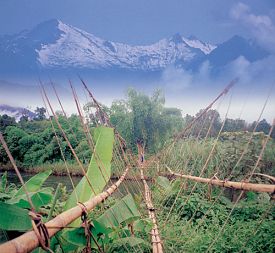

Hkakabo RaziThat led to a trip to Yangon, where it became clear that any expedition would be into one of the most remote areas of the world.

Set in a remote corner of Kachin state near the Chinese border, Hkakabo Razi had not been seen by outsiders in several decades. There weren't even any photographs of it -- at least, none that the Myanmar authorities were willing to release.

"It was a very mysterious mountain," said Ozaki. "Fifty years ago, a British botanist came there, but didn't see the real Hkakabo Razi. Ten years later, another group tried to climb it, but it was too steep. This was the only information we had, and it was not enough."

So January 1995, Ozaki set off on a three-month reconnaissance trek into Myanmar's mountainous far north, with a few dozen porters, a team from the Myanmar Hiking and Mountaineering Federation (MHMF) -- and his son Makato, who was ten years old at the time.

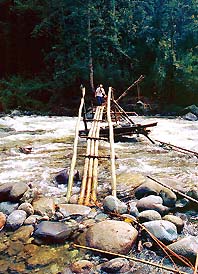

"We were trekking through tropical jungle, fifteen miles a day up and down, and the way was not good at all, very narrow and always hard," Ozaki said. "But we had to see the mountain, to see which route we will take, what equipment we will need, how much rope."

As they approached the mountain, however, heavy snows and the threat of avalanches intervened, making it impossible to set up a base camp for the climb. The weather was so bad that, after climbing a nearby mountain to examine Hkakabo Razi, the clouds never even cleared long enough for them to photograph it.

The approach to Hkakabo RaziThe setback was discouraging, and Ozaki was starting to worry about the threat of being beaten. Two other expeditions -- one French, one Japanese -- had also been granted permission to make an assault on Hkakabo Razi. Under pressure, realizing he would have to improvise a route up the mountain if he were to beat the other teams, Ozaki returned to Yangon to put together a climb as quickly as he could.

In Yangon, he worked feverishly with climbers from the Myanmar Hiking and Mountaineering Federation to put together a strong team, training them in alpine techniques. He had also gleaned some important information from the reconnaissance mission, and now knew the route in to base camp, how many provisions they would need and the difficulties they would face in finding porters to carry the massive amounts of gear and supplies. He also knew that his young son could handle the rigors of the trip. And that was important -- because when they set out again to make an attempt on the summit, Ozaki brought not Makoto, but also his wife and his seven-year-old daughter Sarah.

In early July, they made their first serious attempt on the mountain. "The trip in was just as difficult as the reconnaissance trip, but we saw Hkakabo Razi for the first time," said Ozaki. Leaving his children at base camp, he and his team started up the mountain, and quickly ran into trouble.

"It was much different from my image of it -- I was thinking it would be an easier mountain to climb. But it was very big, very dangerous, with avalanches and falling stones. We crossed a hanging glacier, and came up under the main ridge, which was very risky. But we could reach only 5,000 meters. We had no ladder for crossing crevasses, and the crevasses were starting to open up. So we gave up. We had no choice. It was too dangerous."

Ozaki's failure to anticipate the rough conditions had cost him the summit, but he returned to Yangon in August determined to try again. As his wife went back to her job with the Trade Commission of the French Embassy in New Delhi, Ozaki started to organize another assault.

But after the failure of the first expedition, it was becoming hard to find sponsors to help shoulder the US$65,000 cost of a second attempt. The French Ecole Nationale de Ski et d'Alpinisme stepped in with an offer to train some of the Myanmar climbers, and a few other private companies, including Thai airways, helped out.  Nevertheless, it was becoming clear that if Ozaki was serious about beating the other climbing teams, he would have to move quickly, and he and his wife decided to go ahead with the second climb -- even though they had to fund most of the expedition themselves. Leaving their children in New Delhi, they left Yangon on July 10, flying to the northern town of Putao and trekking in to the mountain.

Nevertheless, it was becoming clear that if Ozaki was serious about beating the other climbing teams, he would have to move quickly, and he and his wife decided to go ahead with the second climb -- even though they had to fund most of the expedition themselves. Leaving their children in New Delhi, they left Yangon on July 10, flying to the northern town of Putao and trekking in to the mountain.

This time, the Ozakis were leaving nothing to chance. Along with MHMF president Dr Paing Soe and eight other team members, they had all the equipment they needed for an extremely rigorous climb, and had made arangements to keep in radio contact with base camp.

Despite the difficulties of the first attempt, the climb was even more dangerous than Ozaki had expected. "We spent 25 days on the actual climb -- I had thought that it would take ten days, maximum two weeks," he said. "I had very strong men, but the snow conditions were bad, and our progress was slowed by avalanches, always avalanches. And every day, rain or snow. So the route was very, very complicated."

One by one, the climbers dropped back, setting up support camps along the side of the mountain as the team climbed in increasingly severe conditions. Despite extensive climbing experience in the Himalayas and on America's Mount McKinley (widely considered by climbers to have the most severe conditions of any mountain on earth), Ozaki wasn't sure they would make it. The weather, he said, was worse than anything he had ever seen, and as they rode out storm after storm, success looked increasingly unlikely.

But finally, on September 15, the weather cleared and Ozaki and Niyama Gyaltsen made it up the final ridge to the summit. Myanmar's highest peak had finally been conquered.

Back in Yangon a few weeks later, Ozaki was already contemplating his next adventure. "They have asked me to climb the second-highest mountain in Myanmar," he said. "But my dream is to bring this Myanmar team to Mt Everest. Already, they have the toughness to do it. I think they may be stronger than the sherpas.

"But now, we'll take a rest," he added. "And next year, exploration. There are so many things to discover here, the village people, the ethnic groups. We'll be back."

(Asia Times , October 8, 1996)