Amy Beth Kirsten's "Colombine's Paradise Theater" at the Atlas

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • November 17, 2013

There’s no simple way to describe “Colombine’s Paradise Theater” — the wildly imaginative new music-theater-dance piece by composer Amy Beth Kirsten, performed at the Atlas Performing Arts Center last weekend. But it’s a tour de force any way you cut it.

Amy Beth KirstenBuilt on a few fragments of 17th-century poetry and some archetypal characters from Venetian commedia dell’arte, it’s a highly stylized, darkly beautiful love story that’s steeped in myth yet utterly modern. There’s no real plot; the players (the virtuosos of the new-music ensemble "eighth blackbird") act out the roles of a young woman and her two suitors. But the story really unfolds in the rich poetic imagery — both musical and visual — in the shadowy, unsettling world Kirsten creates.

Amy Beth KirstenBuilt on a few fragments of 17th-century poetry and some archetypal characters from Venetian commedia dell’arte, it’s a highly stylized, darkly beautiful love story that’s steeped in myth yet utterly modern. There’s no real plot; the players (the virtuosos of the new-music ensemble "eighth blackbird") act out the roles of a young woman and her two suitors. But the story really unfolds in the rich poetic imagery — both musical and visual — in the shadowy, unsettling world Kirsten creates.

Nothing is what it seems in this nocturnal place; musicians shift from role to role, a flute solo turns to a half-whispered soliloquy, a bass drum begins to glow and becomes the moon, and even the landscape itself is played as an instrument. Yet despite the episodic structure of its 11 movements, “Colombine” unfolds with the seamless, compelling logic of a dream.

This was no pleasant little reverie. Kirsten writes in a fiercely expressionist style, probing the inner states of her characters with a sharp stick. “Colombine” felt driven by nightmares, by primitive, urgent memories swimming unwelcomed to the surface. The players — denizens of this murky world — shriek and growl and pound out rhythms on the ground, entwine around one another, engage in luminous duets and stalk one another in intricate dances of love. There’s a beguiling element of the grotesque throughout, and the music is complex and multilayered, rich in allusions, and often extraordinarily beautiful. When the lights come up at the end, you feel as though you’ve awoken from some strange, ancient ritual — and you want to go back.

Much of the credit for this superb production goes to the "eighth blackbird" players, who performed the work masked, in costume, in constant motion — and entirely from memory. Pianist Lisa Kaplan brought nuanced passion to her role as the beleaguered Colombine, flutist Timothy Munro made a fine, sinister Harlequin, and percussionist Matthew Duvall brought the Pierrot role alive as he navigated the vast array of drums and bells that comprised the set itself. The considerable visual poetry of the production, meanwhile, came from the inventive director and set designer Mark DeChiazza.

Enso Quartet at the Terrace Theater

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • November 13, 2013

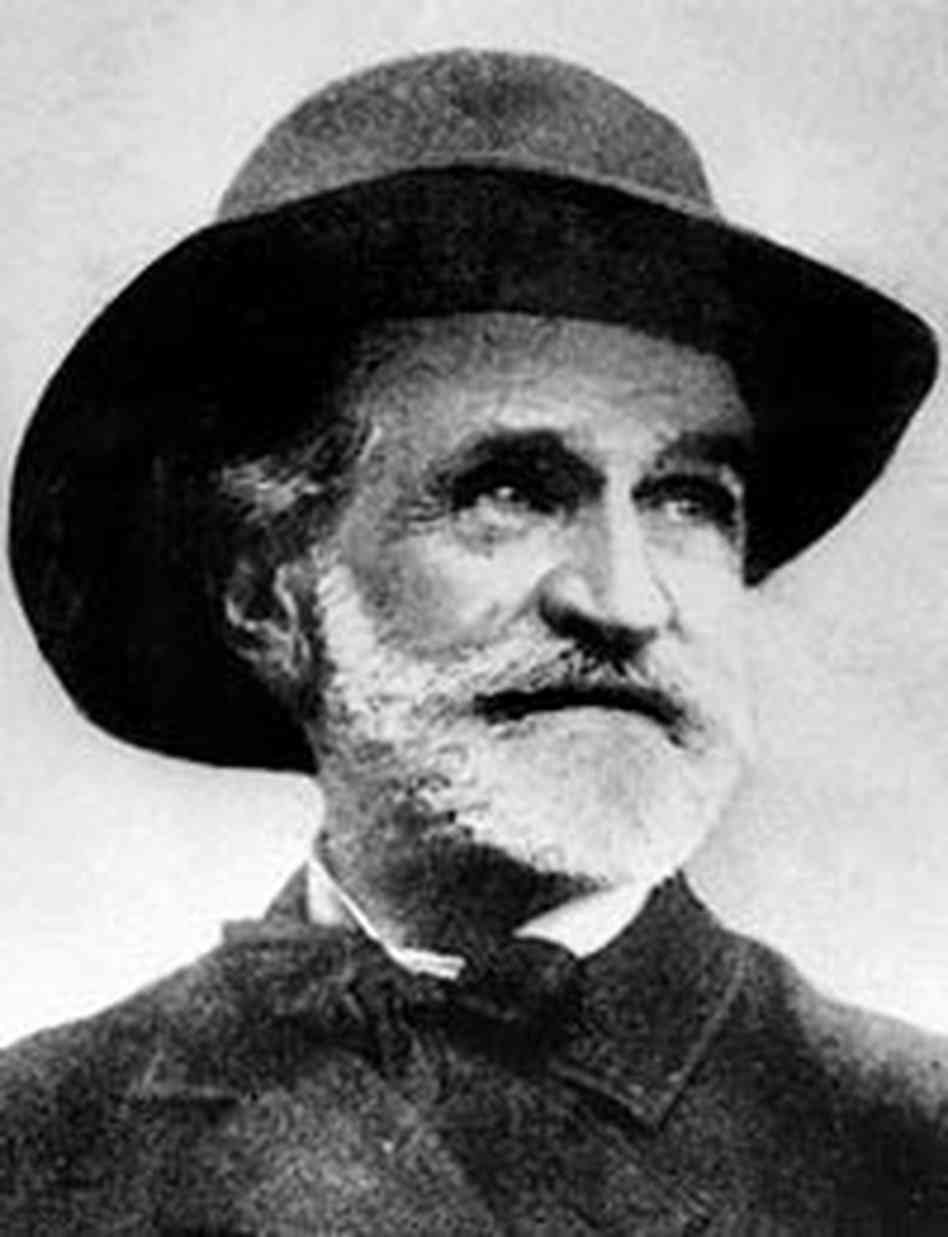

You might expect a string quartet named Enso — after the calligraphic circle that serves as a symbol of Zen Buddhism — to have a certain detachment from earthly things, maybe even an affinity for the pared-down music of John Cage or Morton Feldman. But this young ensemble has gone in the opposite direction, digging up chamber music by 19th-century composers more famous for their operas. At the Kennedy Center’s Terrace Theater on Tuesday, Enso turned in an emphatically non-detached evening of lush, passionate music by Verdi, Puccini and Richard Strauss.

Giusseppe VerdiStrauss wrote his String Quartet in A, Op. 2, in 1880, when he was 16, and as you might expect, there’s teenage posturing (and Mendelssohn worship) in almost every note. But cut the kid some slack; this lavishly romantic quartet might not be quite mature, but it’s skillfully done, full of life and passages of great beauty — particularly the luminous andante cantabile, where Strauss’s emerging musical identity rears its head.

Giusseppe VerdiStrauss wrote his String Quartet in A, Op. 2, in 1880, when he was 16, and as you might expect, there’s teenage posturing (and Mendelssohn worship) in almost every note. But cut the kid some slack; this lavishly romantic quartet might not be quite mature, but it’s skillfully done, full of life and passages of great beauty — particularly the luminous andante cantabile, where Strauss’s emerging musical identity rears its head.

Enso gave Strauss a robust and affectionate reading, then shifted into more serious waters with Puccini’s 1890 “Chrysanthemums.” Ashort but profoundly felt and beautiful work, it was, perhaps, the most deeply satisfying music of the evening, and the quartet brought it off with smoldering power — half honey, half molten lava — and beautifully integrated playing.

Three agreeable, forgettable minuets by Puccini followed before the evening closed with Verdi’s intriguing Quartet for Strings in E Minor. Written almost offhandedly to fill a few empty weeks, it’s the only quartet Verdi composed, and he didn’t use the form to express subtle, intimate musical ideas, as composers tend to do. Instead, there’s an almost theatrical quality to the writing, with big entrances and sotto voce scheming and other exciting goings-on, all tied up with that rarest of rare birds, a Verdi fugue. A great romp all around, and Enso played it with full-throated dramatic intensity. This fine, imaginative ensemble is well worth keeping an eye on.

Steve Antosca's "Habitat" at the National Gallery of Art

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • November 11, 2013

The vast, vaulting atrium of the East Building of the National Gallery of Art — so immense it can feel like a world of its own — is a spectacular place to see art. But it’s an equally spectacular setting for contemporary music, as composer Steve Antosca proved Sunday evening with the world premiere of “Habitat,” a work for computer and percussion that filled the atrium with a surging, often breathtaking ocean of sound — and turned the huge space into an instrument in its own right.

Percussionist Ross KarreAntosca revels in pushing traditional instruments (and instrumentalists) beyond their limits, and “Habitat” is written around a single percussionist who embarks on a 40-minute “transformational journey” upward through the atrium. Opening amid a battery of bells and marimbas in the center of the audience, the young virtuoso Ross Karre moved across the gallery to a “prepared” piano, then on to strum Harry Bertoia’s 17-foot-high “Tonal Sculpture,” then up the stairs to the mezzanine and higher still to the bridge that crosses the atrium at its highest level. As he rose from floor to floor, Karre used different instruments to describe a detailed emotional journey — from gentle to stormy to ethereal — before returning to earth to rekindle the original musical ideas, now darker and more profound.

Percussionist Ross KarreAntosca revels in pushing traditional instruments (and instrumentalists) beyond their limits, and “Habitat” is written around a single percussionist who embarks on a 40-minute “transformational journey” upward through the atrium. Opening amid a battery of bells and marimbas in the center of the audience, the young virtuoso Ross Karre moved across the gallery to a “prepared” piano, then on to strum Harry Bertoia’s 17-foot-high “Tonal Sculpture,” then up the stairs to the mezzanine and higher still to the bridge that crosses the atrium at its highest level. As he rose from floor to floor, Karre used different instruments to describe a detailed emotional journey — from gentle to stormy to ethereal — before returning to earth to rekindle the original musical ideas, now darker and more profound.

But what made this individual “journey” particularly involving — in a physical, even visceral way — was the way Karre’s playing was transformed by computer musician William Brent, then amplified and broadcast through speakers around the atrium. The result was a complex and wildly colorful palette of sound — the stuff that gongs and wood blocks dream of — that seemed to sweep in huge waves from every direction, as if Karre were playing the atrium itself as a gigantic meta-instrument — and we, the audience, were inside. A fascinating and often compelling new work from Antosca, played with exceptional skill by Karre — who also turned in a fine account of John Cage’s magnificent “Cartridge Music” from 1960, which opened the program.

Sophie Shao and Ieva Jokubaviciute at the Phillips Collection

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • October 28, 2013

B

ringing off a whole afternoon of romantic-era music isn’t easy; all that sighing and swooning and hot-blooded emoting can get a little ripe in modern ears after a while. But in a program of Schumann, Brahms and Beethoven at the Phillips Collection on Sunday, the extroverted cellist Sophie Shao — accompanied by the wondrous Lithuanian pianist Ieva Jokubaviciute — found an eloquent balance between rapture and cool restraint, and turned in a deeply satisfying performance.

Despite (or maybe because of) their distinct personalities, Shao and Jokubaviciute seemed ideally paired with each other. Opening with Schumann’s Adagio and Allegro in A-flat, Op. 70, Shao threw her head back and leapt in — hair flying and nostrils flaring in fine romantic abandon — as Jokubaviciute accompanied with quiet precision and delicacy, supporting Shao’s sweeping interpretation but bringing a compelling edge and nuance of her own. It made for romanticism at its best: impassioned, even transporting, but with a clear-eyed intelligence that kept it from overheating into mush.

Despite (or maybe because of) their distinct personalities, Shao and Jokubaviciute seemed ideally paired with each other. Opening with Schumann’s Adagio and Allegro in A-flat, Op. 70, Shao threw her head back and leapt in — hair flying and nostrils flaring in fine romantic abandon — as Jokubaviciute accompanied with quiet precision and delicacy, supporting Shao’s sweeping interpretation but bringing a compelling edge and nuance of her own. It made for romanticism at its best: impassioned, even transporting, but with a clear-eyed intelligence that kept it from overheating into mush.

That finely calibrated interplay marked the entire afternoon. Brahms’s spirited Sonata in E Minor, Op. 38, with its restless and sometimes combative back-and-forth between the two players, was a case study in the art of the duet, and Shao held little back in a warm, glowing reading. Schumann’s Fantasy Pieces, Op. 73, was equally satisfying — the playing just got better as the afternoon progressed — with an almost palpable connection between the players.

But it may have been Beethoven’s Sonata in A, Op. 69, No. 3, that revealed the two at their best. It’s a subtle work with a kind of quiet nobility to it, and Shao brought both power and insight to her playing. But the piece is as much for piano as it is for cello, and Jokubaviciute may have stolen the show a bit in an absolutely jaw-dropping performance — subtle, complex, almost impossibly detailed and riveting in every way. Jokubaviciute is fast emerging as one of the most gifted young pianists on the scene; kudos to the Phillips (and its adventurous music director, Caroline Mousset) for finding and showcasing talent as remarkable as this.

Ivana Gavric at the Phillips Collection

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • October 21, 2013

After surfacing from her deep -- and much-acclaimed -- immersion in the music of Czech composer Leos Janacek a couple of years ago, the British pianist Ivana Gavric embarked on a new journey, this one into the music of Edvard Grieg. She was so intent on understanding the Norwegian composer that she even traveled to see the landscapes that inspired him — and the results were strikingly clear in her impressive, insightful U.S. debut Sunday at the Phillips Collection, where Grieg and Janacek formed the core of a program that linked late romanticism to 20th-century modernism. Gavric’s affection for Grieg was clear from the opening notes of the Piano Sonata in E Minor, Op. 7, written when the composer, heart still firmly attached to sleeve, was only in his early 20s. It’s not played often — maybe because its considerable sound and fury don’t always feel driven by any convincing purpose — but Gavric brought it to life in a fine and impassioned reading. Smaller-scale but more satisfying were the two later miniatures, “Butterfly” Op. 43, No. 1 (which Gavric played with a darting and almost weightless touch) and the rich lyricism of “Peasant’s Song” Op. 65, No. 2.

Gavric’s affection for Grieg was clear from the opening notes of the Piano Sonata in E Minor, Op. 7, written when the composer, heart still firmly attached to sleeve, was only in his early 20s. It’s not played often — maybe because its considerable sound and fury don’t always feel driven by any convincing purpose — but Gavric brought it to life in a fine and impassioned reading. Smaller-scale but more satisfying were the two later miniatures, “Butterfly” Op. 43, No. 1 (which Gavric played with a darting and almost weightless touch) and the rich lyricism of “Peasant’s Song” Op. 65, No. 2.

The cascading torrents of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s finger-breaking “Moments Musicaux” Op. 16, No. 4 rounded off the first, rather romantic half of the program, but the most interesting music came in the second half. Cheryl Frances-Hoad’s recent “2 Lyric Pieces” were sketchlike homages to Grieg and Janacek done in an improvisatory and almost jazzy style, and the afternoon closed with a furiously virtuosic account of Sergei Prokofiev’s Piano Sonata No. 2 in D Minor, Op. 14.

The real heart of the program, though, may have been Gavric’s multilayered reading of Janacek’s “In the Mists.” Delicately woven, shifting subtly between light and shadow, the work’s dark mysteries unfolded with rare insight; it was a ravishing performance.

Dublin Guitar Quartet at the Phillips Collection

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • October 14, 2013

The classical guitar may have a quiet voice, but it makes up for it with a striking array of sonic colors, from drumming to delicate harmonics. Put four of the instruments together, and you have the best of both worlds: intricate detail and a near-orchestral palette of sound backed up by hall-filling power. That, anyway, was the takeaway from the Dublin Guitar Quartet’s engaging recital at the Phillips Collection on Sunday, when the Irish ensemble presented a varied program of contemporary music that revolved around the minimalist axis of Philip Glass, Steve Reich and the Estonian composer Arvo Pärt. The afternoon opened (fittingly enough, after the drenching week) with Leo Brouwer’s “Cuban Landscape with Rain,” a tone poem evoking the shifting rain and winds of a passing storm. The Dublin players gave it an evocative reading, full of atmospheric turbulence and finely graded shades of light. Pärt’s “Summa” (in a transcription from the choral original) was just as luminous, very moving in its spare simplicity and its dignified, quiet grace.

The afternoon opened (fittingly enough, after the drenching week) with Leo Brouwer’s “Cuban Landscape with Rain,” a tone poem evoking the shifting rain and winds of a passing storm. The Dublin players gave it an evocative reading, full of atmospheric turbulence and finely graded shades of light. Pärt’s “Summa” (in a transcription from the choral original) was just as luminous, very moving in its spare simplicity and its dignified, quiet grace.

The quartet shifted gears for “Chimurenga” by David Flynn (a tribute to the Zimbabwean composer Thomas Mapfumo) which shimmered with lilting, African-flavored melodies, then ventured into rock music with the lyrical “Soundscapes Over Landscapes” by the Dublin rock band The Redneck Manifesto. “Musica Ricercata,” a collection of precise little miniatures from the 1950s by György Ligeti, tied up the concert with modernist style.

But the real heart of this refreshingly eclectic program was the music of Glass and Reich. That’s not necessarily a bad thing (though minimalism, to these ears, is starting to show its age), and Pat Brunnock (on electric guitar, with taped accompaniment) gave a driving account of Reich’s “Electric Counterpoint.” But Glass’s obsessive, repetitive music continues to divide audiences, and for every listener who finds it glowing with transcendent beauty, there’s another who thinks it’s like chewing on a rubbery piece of chicken — much work, little actual reward. The Dubliners offered up arrangements of Glass’s second string quartet (“Company”) and two movements of his fourth (“Buczak”) which, while easy enough on the ears, probably didn’t win converts to either side of the debate.

Claire Chase at the Atlas

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • October 13, 2013

Does the flute have a more interesting champion right now than Claire Chase? At 35, this New York-based virtuoso has carved out a key role for herself in contemporary music, commissioning and performing a range of new works for flute that have brought much-needed fire to the repertoire. The indefatigable Chase — she’s also a founder of the International Contemporary Ensemble and a 2012 MacArthur Fellow — has just released her third CD, titled “Density.” On Saturday night at the Atlas Performing Arts Center, she put on a riveting performance of the music from that disc: a 75-minute tour de force that showed Chase to be among the most electrifying flutists on the planet — and showed the flute as an instrument whose possibilities have only begun to be explored.

The indefatigable Chase — she’s also a founder of the International Contemporary Ensemble and a 2012 MacArthur Fellow — has just released her third CD, titled “Density.” On Saturday night at the Atlas Performing Arts Center, she put on a riveting performance of the music from that disc: a 75-minute tour de force that showed Chase to be among the most electrifying flutists on the planet — and showed the flute as an instrument whose possibilities have only begun to be explored.

Chase tossed out the usual concert conventions, performing alone — accompanied only by electronics or her own pre-recorded flute tracks — and dressed near-invisibly on an almost dark stage, playing the entire program as a highly amplified and uninterrupted whole. The effect was spellbinding. As each work moved seamlessly into the next, Chase explored different forms of density — of textures, of thought, of sheer sonic weight — gradually narrowing the focus from the playful 11-flute orchestra of Steve Reich’s “Vermont Counterpoint” to the climactic, elemental intensity of Edgard Varese’s 1936 masterwork for solo flute, “Density 21.5.”

And through all the works — which included Marcos Balter’s dark and deeply poetic “Pessoa” for six bass flutes; Alvin Lucier’s maddening but strangely beguiling “Almost New York” for flutes and sustained sine tones (patience required); Mario Diaz de Leon’s idea-dense “Luciform” (a vibrant sort-of-sonata for flute and electronics, from 2013); and Philip Glass’s tail-chasing “Piece in the Shape of a Square” for two flutes — Chase played with the kind of vitality and directness and effortless virtuosity that you always hope to hear in the concert hall but too rarely do. All in all, an extraordinary evening from one of the brightest lights on the contemporary music scene, and a high point of the Atlas’s ongoing New Music series.