Capitol Woodwind Quintet: 20th Century Gems

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • May 13, 2008

____________________________________________________________________________

If you're interested in surprising little adventures down rarely trod musical byways, it's always worthwhile to see what the Capitol Woodwind Quintet is up to. They've proved themselves adept at finding lyrical, smile-inducing gems of 20th-century music, and playing them with brainy wit. And on Sunday at Temple Micah they did it again, presenting several works from the last century that were both intellectually satisfying and gorgeous to the ears. Take "Sciarada Spagnuola," a 1963 work by the Dutch composer Jurriaan Andriessen that opened the concert. "I think I had that for dinner last night," joked one audience member, and in fact this lilting work -- a suite of dance movements that echoes polyphonic Renaissance music -- proved to be a fine appetizer to the rest of the program. The quintet displayed both virtuosity and near-telepathic communication (the group's played together for three decades) in Antonin Reicha's 1817 Quintet in G, Op. 88, No. 3, dispatching it with an elegant lightness that made it seem completely fresh.

Take "Sciarada Spagnuola," a 1963 work by the Dutch composer Jurriaan Andriessen that opened the concert. "I think I had that for dinner last night," joked one audience member, and in fact this lilting work -- a suite of dance movements that echoes polyphonic Renaissance music -- proved to be a fine appetizer to the rest of the program. The quintet displayed both virtuosity and near-telepathic communication (the group's played together for three decades) in Antonin Reicha's 1817 Quintet in G, Op. 88, No. 3, dispatching it with an elegant lightness that made it seem completely fresh.

But the most interesting fare of the evening came after intermission. The Swedish composer Lars-Erik Larsson only wrote one wind quintet, but it's a doozy: the "Quattro Tempi," Op. 55 from 1968. The title refers to the four seasons, and the quintet turned in an evocative, sometimes even magical, account -- a lush and tranquil summer turned into a quickening scramble as fall approached, then sank into the somber mysteries of winter before spring arrived, explosive with life.

The program closed with Jean-Michel Damase's "Dix-Sept Variations," Op. 22, a work from 1952 that embodies French charm itself. Playful, inventive and unfailingly melodic, it wears its harmonic complexities lightly and with considerable style, and received a superb performance from this fine ensemble.

Wynton Marsalis at the Kennedy Center

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • May 9, 2008

________________________________________________________________________________

If you're launching a jazz education program, there's no better friend to have than Wynton Marsalis. The acclaimed trumpeter may be the country's best-known jazz musician, and he's virtually a spokesman for the music itself. So it was fitting that Marsalis and his Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra inaugurated the new Capitol Jazz Project (a joint venture by the Washington Performing Arts Society and the D.C. public school system to support music in middle schools) with a program of traditional jazz at the Kennedy Center Concert Hall on Wednesday night.

If you're launching a jazz education program, there's no better friend to have than Wynton Marsalis. The acclaimed trumpeter may be the country's best-known jazz musician, and he's virtually a spokesman for the music itself. So it was fitting that Marsalis and his Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra inaugurated the new Capitol Jazz Project (a joint venture by the Washington Performing Arts Society and the D.C. public school system to support music in middle schools) with a program of traditional jazz at the Kennedy Center Concert Hall on Wednesday night.

Marsalis has caught a lot of flak over the years for his conservatism; he's notoriously disdainful of most jazz after 1960 (including late Coltrane, fusion and free jazz) and is often accused of merely popularizing the classics, instead of being a true innovator. Wednesday's concert seemed to bear that out: Marsalis and his 15-piece band played familiar works by Thelonious Monk and Duke Ellington, with some newer pieces by Marsalis himself and members of the group that stayed safely within traditional bounds.

And while the playing was superb -- this is a tightly knit ensemble that cuts through even the most complex music with jaw-dropping precision -- the evening felt distinctly tame and well-mannered, as if the band were gliding on well-worn tracks instead of channeling the spontaneous, risk-taking ferocity that makes jazz what it is. Rather than edge, there was elegance: Marsalis's shimmering, impressionistic take on the "Pollock" section of "Portrait in Seven Shades" (by the gifted reed player Ted Nash) was drop-dead gorgeous, and Joe Temperley's eloquent bass clarinet solo on Ellington's "The Single Petal of a Rose" won't soon be forgotten by anyone who heard it. The sold-out crowd gave Marsalis a standing ovation after the show closed with his fine, driving "Vitoria Suite."

Del Tredici's "Final Alice" Returns

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • May 8, 2008

________________________________________________________________________

It was the most outrageous thing the music establishment could have imagined. Here was Sir Georg Solti leading the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in a new work by a leading avant-garde composer, and there were . . . arias! With actual melodies! Contemporary music, as everyone knew, was supposed to be thorny and atonal stuff, with no use for the outdated conventions of the past. Yet here was bar after bar of lush, unrepentant harmony, hummable tunes, symphonic gestures right out of Mahler. Even a fugue. To the ruling avant-garde it was a slap in the face -- and as a final insult, the audience leapt to its feet, cheering, when the piece came to a close.

It was the most outrageous thing the music establishment could have imagined. Here was Sir Georg Solti leading the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in a new work by a leading avant-garde composer, and there were . . . arias! With actual melodies! Contemporary music, as everyone knew, was supposed to be thorny and atonal stuff, with no use for the outdated conventions of the past. Yet here was bar after bar of lush, unrepentant harmony, hummable tunes, symphonic gestures right out of Mahler. Even a fugue. To the ruling avant-garde it was a slap in the face -- and as a final insult, the audience leapt to its feet, cheering, when the piece came to a close.

It was Oct. 7, 1976, and the work was "Final Alice" by 39-year-old composer David Del Tredici. Until that moment, he'd been a card-carrying member of the avant-garde. But in one bold stroke, Del Tredici jettisoned the strict composing system known as serialism (which dominated new American music, to the despair of most audiences) and embraced a neo-romantic style -- scandalizing his colleagues and setting off an earthquake in American music whose aftershocks are still being felt.

" 'Final Alice' changed the face of music in this country overnight," recalls Leonard Slatkin, the National Symphony Orchestra's music director, who was in the Chicago audience that night. "It destroyed all conceptions of what 'new music' was supposed to be, and many composers will tell you that they were now liberated to write how they felt. It was the start of a revolution."

Slatkin is bringing the complete work to the Kennedy Center for the first time this weekend, and it promises to be a spectacle. A sort of opera in concert form, "Final Alice" is drawn from Lewis Carroll's "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland" and is just as wildly imaginative as the original. Spoken and sung by an amplified soprano (the remarkable Hila Plitmann, in her NSO debut) who at one point sings through a bullhorn, it calls for a gargantuan orchestra augmented by sirens, a theremin and an amplified "folk group" of saxophones, a mandolin, a banjo and an accordion.

"It's a retro piece in the aspects of melody and harmony and rhythm -- literally a return to tonality," Slatkin says. "But the sounds are just insane."

And that's probably appropriate for the plot of "Final Alice," which focuses on the last two chapters of Carroll's book. It tells the story of an edgy, nonsensical trial (someone stole some tarts) that starts out lightheartedly but ratchets steadily into pandemonium, until the Queen shouts "Off with her head!" -- and Alice wakes back in reality.

But it wasn't the story that intrigued Del Tredici as much as the story behind the story. The Alice-in-Wonderland tale, as is well known, was actually written by the Rev. Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a respected English mathematician and logician. Greatly taken with a young girl named Alice Pleasance Liddell, he made up the tale for her and her sisters, publishing it in 1865 under the pen name Lewis Carroll. With its puns, logic games and engagingly absurd rhymes, the book became a classic of children's literature.

David Del Tredici, in his "Alice" yearsBut there have long been disturbing questions about Dodgson's relationship with Alice Liddell. He clearly was infatuated with the child, and -- while there's no solid evidence that he was a pedophile -- Dodgson was known to be extremely interested in young girls, avidly searching them out, befriending them, even taking nude photographs of them. The Liddell family eventually broke off relations with him, for reasons never fully explained.

And yet, while scholars agree that Dodgson was almost certainly in love with Alice (there's a persistent rumor that he proposed marriage to her in 1863, when she was all of 11), he seems to have repressed any sexual feelings he may have had. "He probably felt more than he dared acknowledge, even to himself," biographer Morton N. Cohen has suggested.

That story of forbidden love caught Del Tredici's imagination.

"What inspired me to do 'Alice' was partly Lewis Carroll, and partly Martin Gardner, who wrote 'The Annotated Alice,' " says the New York-based composer, now 71. Gardner's 1960 book showed that many of Carroll's nonsense verses were based on popular songs of the day, and pointed to secret meanings in the work. Particularly interesting was a love song called "Alice Gray," by William Mee, about a man's unrequited passion for a girl named Alice.

"I wanted to put in the true story of Carroll," Del Tredici says. "His love for Alice, whatever it was. And since these were forbidden poems -- the truth, let's say, about Carroll -- I would set them in the forbidden language, which at that time was, of course, tonality. So in a way I use the tonality in 'Final Alice' as a metaphor -- an image of 'forbiddenness' unveiled."

Metaphor or not, the leap into tonality was a bold move. Composers in the 1970s saw themselves as being in the vanguard of a revolution, forging a new musical language built on the 12-tone system of Arnold Schoenberg. Tonality belonged to the past, and audiences were treated as almost irrelevant. "Who Cares if You Listen?" asked Milton Babbitt, one of the leading serialists of the day, in the title of a celebrated essay.

"It was inconceivable at the time to write tonally," Del Tredici says. "I thought, I cannot do this -- my colleagues will think I'm nuts! But I realized that my instinct had given me these tonal chords with the same excitement it used to give me minor ninths and minor seconds, so I decided to go with my instinct. I went back and finished the piece and hoped for the best."

And the music is revelatory. The words of the innocent, sweeping aria that opens the work are right from the book. But as the drama unfolds, the singing gets increasingly edgy and tormented. New texts are introduced, the arias swell with anguish, and as the lid is torn from Carroll's secret love, the music explodes. Tempos leap madly around, the theremin wails, sirens shriek, and the soprano hurtles herself against the furthest reaches of her range. From light, amusing children's fantasy, "Final Alice" turns into something much different -- a gripping portrayal of turmoil in the human heart.

And the music is revelatory. The words of the innocent, sweeping aria that opens the work are right from the book. But as the drama unfolds, the singing gets increasingly edgy and tormented. New texts are introduced, the arias swell with anguish, and as the lid is torn from Carroll's secret love, the music explodes. Tempos leap madly around, the theremin wails, sirens shriek, and the soprano hurtles herself against the furthest reaches of her range. From light, amusing children's fantasy, "Final Alice" turns into something much different -- a gripping portrayal of turmoil in the human heart.

The work was a popular triumph, and it shot Del Tredici into the limelight. ("Before 'Final Alice,' I was a respected composer," he says. "After it, I was either loved or hated.") Solti recorded it, and a subsequent commission from Slatkin resulted in 1980's "In Memory of a Summer Day," which won the Pulitzer Prize. A major shift toward tonality had begun in American music, launched almost single-handedly by "Final Alice."

But even as neo-romanticism settled firmly into the American musical mainstream -- marked by such works as Mark Adamo's "Little Women" -- Del Tredici kept pushing at the edges. Like Carroll, he had his own demons, and after winning the Pulitzer he went through what he calls "a kind of personal breakdown" marked by alcoholism and sex addiction. Fighting his way back into balance, he says, changed his identity as a composer.

"Coming out of that breakdown brought me some personal exploration, and that got me into being out about being gay," he says. "I'd always been personally out as a gay man, but to actually make it a public expression of my music -- I would never have done that unless I felt I had somehow crashed and come back."

The result has been a string of works as shocking in their own way as "Final Alice" was -- songs celebrating gay life, often built around pornographic texts by writers such as Allen Ginsberg. It's a controversial path, but Del Tredici says he needs to trust his instincts -- the same ones that brought him so famously to tonality -- even if they result in music considered too outrageous to be widely performed.

"I often get tarred for my passions, but I feel I have no choice: Music is passionate to me," he says. "And music is about passion, no matter how much to the contrary in the 20th century we may have been told."

So he's become a maverick once again?

"Yes!" the composer says, laughing. "In my 70s, I'm still being a bad boy."

Poulenc Trio at the National Gallery of Art

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • May 6, 2008

________________________________________________________________________

The Poulenc TrioDisparage the music of Francis Poulenc if you want to -- there's still no finer stuff for a beautiful evening in May, when the zephyrs are breezing (or whatever zephyrs do), and the land purely brims with flowers and light and chirping birds. At least, that's how it seemed at the National Gallery of Art on Sunday, when the Poulenc Trio -- oboist Vladimir Lande, with Bryan Young on bassoon and Irina Kaplan Lande at the piano -- brought an intriguing and beautifully played program to the West Garden Court.

The trio opened with two 19th-century works, Beethoven's Trio in B-flat, Op. 11, and Mikhail Glinka's 1832 "Trio Pathetique" in D Minor. It's perhaps not the most natural music for the thin-voiced double reeds, but oboist Lande showed he could turn even the most sweeping, violinistic phrases with convincing elegance. Bassoonist Young was equally adept, but unfortunately was often drowned out by the piano; anyone who's been to a concert at the West Garden Court will attest to the bottom-of-the-well acoustics of the place, which show no mercy to quiet instruments.

The high point of the evening, though, was Poulenc's Trio for Piano, Oboe and Bassoon from 1926. It's an urbane, sophisticated piece that unfolds with near-effortless lightness and grace, and these players clearly have it in their collective bloodstream. Andre Previn's 1994 Trio for Oboe, Bassoon and Piano was less satisfying, though. A conventionally tonal piece that draws on a smorgasbord of styles (a little Schumann, a little jazz, a little Sam Barber), it came across as effortful and eager to impress, and it was a relief when the ensemble returned with Astor Piazzolla's lush, shamelessly seductive "Oblivion."

Varèse, Scelsi at the Kennedy Center

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • April 30, 2008

_______________________________________________________________________________

Juan Pablo IzquierdoIt was an emotional evening for many at the Kennedy Center Concert Hall on Tuesday night, when Juan Pablo Izquierdo, the music director of the Carnegie Mellon University Philharmonic, took the podium. It was his final performance after 17 years with the group -- years in which he's built the orchestra into an accomplished interpreter of contemporary music, performing composers from Schoenberg to George Crumb. And from the first notes of "Arcana" -- the brash Edgard Varèse powerhouse that opened the program -- to the close of Stravinsky's epoch-making "Rite of Spring," it was clear that those years have been well spent: Izquierdo is an impassioned and insightful conductor who unleashes 20th-century music in all its raw, explosive glory.

"Arcana," from 1927, is a work that needs to be experienced in the concert hall; recordings never really capture the huge blocks of sound that Varèse sends hurtling through space, or the elemental force that builds, like a juggernaut, for 20 minutes. And although the Carnegie Mellon players are all students, and understandably lack some of the polish and precision of a professional orchestra, Izquierdo drew a bold and exciting performance from the group that more seasoned players would have been proud of.

Things quieted down considerably for Giacinto Scelsi's ethereal "Quattro Pezzi" from 1959, for chamber orchestra. Some think Scelsi a charlatan, a nut job, or both; his mature works are marked by a focus on long, sustained notes, which build in intensity through ultra-subtle changes in dynamics and texture, and they're not for everyone. But the Carnegie's reading of the provocative "Quattro Pezzi" (whose four sections each consist of a single tone) was exceptionally beautiful, a slow blossoming of elegant sound worlds shimmering with light and grace -- enough to make a believer out of anyone.

Berta Rojas plays Barrios

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • April 28, 2008

_________________________________________________________________________

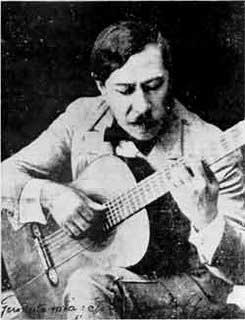

Agustín Pío Barrios was one of the 20th century's most intriguing -- not to say eccentric -- composers. Born in Paraguay in 1885, he spent a frustrating career as a guitarist-composer, often mocked for his unconventional repertoire and for using metal guitar strings rather than the conventional gut. A true original (he was the first classical guitarist to make recordings), Barrios also reinvented himself in his mid-40s as a Guarani tribal chief, performing in native costume and calling himself Cacique Nitsuga Mangoré, "the Paganini of the guitar from the jungles of Paraguay."

Agustín Pío Barrios was one of the 20th century's most intriguing -- not to say eccentric -- composers. Born in Paraguay in 1885, he spent a frustrating career as a guitarist-composer, often mocked for his unconventional repertoire and for using metal guitar strings rather than the conventional gut. A true original (he was the first classical guitarist to make recordings), Barrios also reinvented himself in his mid-40s as a Guarani tribal chief, performing in native costume and calling himself Cacique Nitsuga Mangoré, "the Paganini of the guitar from the jungles of Paraguay."

Barrios died, largely unsung, in 1944. But he left behind some of the most engaging and beautifully crafted guitar music ever written, and on Saturday evening the gifted Paraguayan guitarist Berta Rojas presented an all-Barrios program at Westmoreland Congregational Church, as part of the always interesting John E. Marlow Guitar Series.

Rojas clearly has Barrios's music deeply in her blood; playing entirely from memory, she traversed the composer's stylistic range, from the poignant "El Ultimo Canto" and classically inspired works like "Estudio de Concierto" and "Allegro Sinfonico," to pieces like "Julia Florida" and "Jha che Valle" (with their roots in Latina American folk music) and Barrios's extraordinarily beautiful masterpiece, "La Catedral."

And when Rojas is at her best, there may be no better Barrios interpreter alive. Often in the faster works, she tended to push tempos to the brink, smearing the details. But on the whole, these were intimate, introspective performances (the moving "Choro de Saudade" seemed to come directly from her heart), rich in subtle colors and intuitive understanding of Barrios's complex personality

Verge and Aleph at the Embassy of France

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • April 28, 2008

______________________________________________________________________________

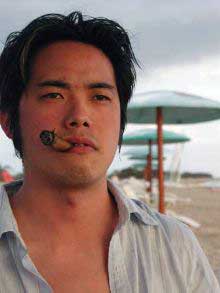

Ken UenoThe Verge Ensemble, the adventurous new-music group in residence at the Corcoran Gallery, joined forces with the Paris-based Ensemble Aleph on Friday for a concert at the Embassy of France that demonstrated the value of trans-Atlantic cooperation in areas beyond mere trade and politics. Mingling their personnel, the two groups gave a nod to the past with a graceful reading of Ravel's Piano Trio in A Minor, but focused on edgier works written in the last decade or two.

The composer Ken Ueno amplifies traditional instruments to uncover new worlds of sound, and his "Contemplation on Little Big Muff" gave Christophe Roy's amplified cello a strange and unsettling intensity, probing into sustained tones and building drama from the timbral textures that were revealed. There were few concessions to loveliness, but the piece had a fascinating, elemental power that resonated long after it ended.

More immediately delectable were the two "Recitations" by French composer George Aperghis, sung with charming delicacy by the elfin soprano Monica Jordan. Light, playful works for solo voice, they hover somewhere between song and sound poetry, drawing on a range of effects from birdlike fluttering to deep-voiced growls.

Christopher CulpoA lullaby with a war scene in it is an intriguing idea, but Paolo Prestini's "As Sleep Befell" -- while often lovely -- never quite gelled, drifting instead through a landscape of soft edges and earnest intentions. Dominique Clement's "Let's Go" was more colorful, incorporating taped snatches of film dialogue into a lively, lilting piece. But "After Midnight, Before Dawn" by Christopher Culpo was the real gem of the evening. Written for string quartet with two percussionists, it's a strikingly vivid work that explores the elusive worlds of sleeping and dreaming, to hallucinogenic effect.