Todd Rundgren at the Birchmere

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • December 18, 2007

_______________________________________________________________

Todd Rundgren wasn't too thrilled about the 7:30 start to his show at the Birchmere on Sunday night. "I should be in a daze somewhere," he said, a little wishfully, as he peered through dark glasses at the sold-out house.

Todd Rundgren wasn't too thrilled about the 7:30 start to his show at the Birchmere on Sunday night. "I should be in a daze somewhere," he said, a little wishfully, as he peered through dark glasses at the sold-out house.

Well, sure -- we all should. But Rundgren quickly got down to some serious rock-and-roll, unleashing a loud, wild two-hour set that showed why he's still one of the most unpredictable musicians around. Opening with the beautiful "Buffalo Grass," Rundgren ranged over most of his four-decade career, playing everything from "Black Maria" (off his 1972 breakthrough masterpiece, "Something/Anything") to "Soul Brother" and "Mammon."

It was an unusual set, though, that focused largely on Rundgren's less-familiar work and a couple of oddities. Career-making songs like "Hello It's Me" and "Can We Still Be Friends" were nowhere to be found; the only big hit was "I Saw the Light" (which made it to No. 16 in 1972), and Rundgren played it as if he hated it and wished it would die -- which, more or less, is what it did.

And, frankly? Rest in peace. Rundgren can write a pretty pop tune with the best of 'em, but there's a lot more to listen to in songs like the bluesy "No. 1 Lowest Common Denominator." Besides, the show was more about hard-driving rock than tuneful ballads; Rundgren and the band (featuring the brilliant Jesse Gress on guitar, with Kasim Sulton on bass and Michael Urbano on drums) even tore through a cover of "Lunatic Fringe"(1981) by the one-hit wonder the Red Riders. It never sounded better.

And for a guy pushing 60, Rundgren still works hard, digging into the vocals and closing most songs with a leaping scissors kick. But his promises to "offend each and every person in the room" didn't quite deliver, starting with a tame "Fascist Christ" and ending with a listless jab against -- yawn -- neoconservatives. Sorry; if you want to talk politics in this town, you have to hit a lot harder than that.

Anabel Montesinos at Westmoreland

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • November 19, 2007

_______________________________________________________________

Anabel Montesinos There may be little music more inherently "guitaristic" than the lyrical, evocative works of 20th-century Spanish composers like Joaquin Rodrigo and Isaac Albeniz. Perhaps that's why the young Spanish virtuoso Anabel Montesinos chose a largely Iberian program for her concert Saturday night at Westmoreland Congregational Church, applying her spectacular technique to works like Rodrigo's "Tres Piezas Espanolas," Albeniz's "Asturias" and works by Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco and Manuel Quiroga.

And -- despite being virtually fenced off from the audience by an intrusive microphone setup -- Montesinos brought them all off with style and grace. There's a rare delicacy to her touch that works well with this music, but she's no cringing flower; the charging rhythms of the "Zapateado" movement of the Rodrigo came off with fine, resolute power as well.

The tone shifted in the second half of the concert, when Montesinos was joined onstage by the Cuban guitarist Marco Tamayo -- who is also her teacher and fiancé. The mix of virtuosity and love made for some passionate music; playing their distinctive styles against each other (she sweet and almost impetuous, he darker and more powerful), the pair brought off Bach's "Italian" Concerto and a sonata by Paganini with near flawlessness.

But the most engaging moment may have been the encore: a piece, Tamayo announced, "for four hands and one guitar." As Montesinos played Mozart's famous "Alla Turca" rondo, Tamayo crouched behind her, his face next to hers, reaching around to play the bass line on the lower strings. He nuzzled, and plucked. She blushed, and plucked faster.

Mozart may never be the same.

Shafer's Return

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • November 19, 2007

_______________________________________________________________

There's rarely been a more surprising move than the firing last year of Robert Shafer as music director of the Washington Chorus. Despite having led the group to glory -- and a Grammy Award -- over a 35-year career, Shafer was dumped so abruptly that it led to a near-mutiny, and some 90 choristers followed him out the door. Shafer has now shaped those singers (and about 15 newcomers) into a feisty rival group called the City Choir of Washington -- which, to judge by its triumphant debut Friday night at the Schlesinger Concert Hall and Arts Center, is about to give the Washington Chorus some serious competition.

There's rarely been a more surprising move than the firing last year of Robert Shafer as music director of the Washington Chorus. Despite having led the group to glory -- and a Grammy Award -- over a 35-year career, Shafer was dumped so abruptly that it led to a near-mutiny, and some 90 choristers followed him out the door. Shafer has now shaped those singers (and about 15 newcomers) into a feisty rival group called the City Choir of Washington -- which, to judge by its triumphant debut Friday night at the Schlesinger Concert Hall and Arts Center, is about to give the Washington Chorus some serious competition.

Shafer picked Handel's great oratorio "Solomon" for the launch, and it was an inspired move. It's not much as a story, but the music is astoundingly rich, full of complex choral polyphony (most of it in eight parts), fugues and double fugues, delicate arias, love duets, intricate motets -- with a chorus divided into two sections. Shafer drew a virtuosic performance from the ensemble: detailed and powerful, with superb balance and control over his forces.

In fact, the chorus was really the star of the evening. Among the soloists, soprano Amanda Gosier was the standout, propelling the drama with a lovely voice and a subtle, eloquent sense of theater.

Battling a cold, Darryl Taylor started out beautifully, but his fine countertenor was fading badly by the end of the evening. The promising young soprano Angeli Ferrette, meanwhile, brought a nice electric edge to the baby-chopping role of Second Harlot, while tenor Ole Hass soldiered through what must have been an off night; it happens.

On the whole, though, it was an impressive debut. The City Choir's next performance is Dec. 21 in the same venue, and -- coincidentally or not -- the Washington Chorus will be performing the same night at Strathmore. Let it begin.

In the Sanctuary: Roger Reynolds

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • November 18, 2007

____________________________________________________________________

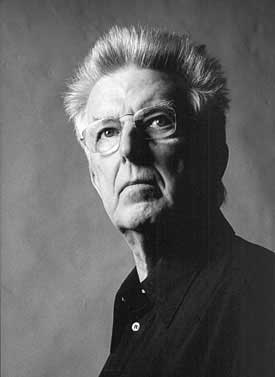

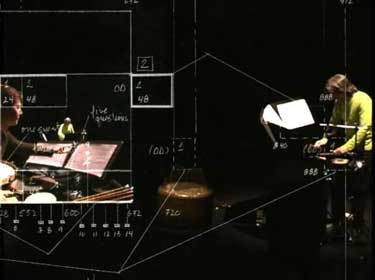

Roger Reynolds Photo: Malcolm Crowthers Tonight at 6:30, the guards at the National Gallery of Art will close and lock the doors of the East Building, sealing it off from the outside world. And in the vaulting atrium -- where Alexander Calder's 76-foot-long mobile famously turns -- a strange and almost otherworldly ritual will start to unfold. Grouped around a bizarre-looking piece of metal called the Oracle, a quartet of percussionists will begin to play, passing fragments of sound back and forth, posing "questions" to the Oracle and responding to its answers. And slowly, gradually, as the percussive clatter begins to cohere, intricate melodies and complex harmonies will emerge -- as if song, or maybe even language itself, were first being born.

It's like a scene out of a primitive past, but "Sanctuary" -- a new work by the Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Roger Reynolds -- is about as cutting edge as it gets. These percussionists won't just be banging on drums; every sound they make will be fed into a computer, transformed in real time into strange and wildly complex new forms, then channeled throughout the vast expanse of the atrium through a carefully placed network of speakers.

It's music, in a sense, for meta-musicians -- players who can turn the tiniest movements of their fingers into waves of sound so gigantic they can fill a cathedral.

"This is an extension of human capacity -- of doing things which could otherwise not occur," Reynolds says. "The gestures become larger than life, allowing the acts of the percussionist to take on larger significance."

For Reynolds, 73, "Sanctuary" is the latest -- and perhaps most intriguing -- in a series of technologically advanced works he's been mounting for decades, incorporating everything from theater to computers to experimental psychology, to extend the boundaries of human listening. The founding director of the Center for Research in Computing and the Arts at the University of California at San Diego, he's that rarest of musical birds -- a composer as much at home at the bleeding edge of technology as he is in the more traditional world of music.

Performing "Sanctuary" at the National GalleryIt's also unusual to find a composer as committed to electronic music as Reynolds is; most seem to view it as a quaint artifact of the 1960s and continue to write for traditional instruments in traditional settings. It's an attitude Reynolds -- who, significantly, was originally trained as an engineer -- finds hard to fathom.

"There's a great deal of resistance to using computers in music -- they're seen as inhuman," he says. "But the computer has the capacity to take what was in the province of the imagination, and turn it into experience. And this is new in human history."

Technology has also allowed Reynolds to bring music out of the concert hall and into places like the Guggenheim Museum and Kenzo Tange's Olympic Stadium in Tokyo, settings that have dramatically altered the relationship between performer and audience. In tonight's concert, listeners will be placed on all three levels of the atrium, some of them changing position between movements.

"There's nothing else like this piece, especially in terms of technology. It's among the newest things in the world," says percussionist Steve Schick, who will be leading the ensemble red fish blue fish in the hour-long, three-movement work. Aided by the CRCA's Ian Saxton and Jacob Sudol on a computer, the group will be using cutting-edge software (designed by the University of California's Miller Puckette), as well as lighting and staging designed to create something beyond the usual concert experience.

For all its advanced and unusual technology, the work had the humblest of beginnings -- as a crayon sketch in (perhaps appropriately) a Greek restaurant.

"It was one of those places that has paper tablecloths and crayons to keep the kids busy," says Schick. "I asked him about doing a new piece, and we started sketching things out. And as this diagram materialized, it seemed like it was almost a flow chart for the history of contemporary percussion music. In one sense, it's a piece about percussion itself."

Schick himself will be wired directly into a computer via motion sensors -- small piezoelectric devices attached to his fingers -- that will turn even the most delicate gestures into new sounds. Amplified throughout the cathedral-like space of the atrium via a dozen speakers, the effect radically alters perspective and scale in surprising ways.

But the most intriguing aspect of the work may be the Oracle itself. It's a "waterphone": a unique, handmade instrument with what Reynolds calls a "beguiling" voice and an unusual background.

But the most intriguing aspect of the work may be the Oracle itself. It's a "waterphone": a unique, handmade instrument with what Reynolds calls a "beguiling" voice and an unusual background.

"We were looking for an instrument that had a sophisticated palette of sounds," says Schick. "And we came across this old piece of junk, made by somebody far before our time. It's the canister of a washing machine, to which about fifty metal rods of different lengths have been welded. You can play the body of the canister -- which is a sort of noisy, reverberant instrument -- and then the little metal rods create individual tones in a kind of scale."

Whatever predictive powers it may have, the Oracle is at the heart of the meaning of the piece, which explores intersecting ideas of communication, sanctuary and, ultimately, authority. The work is structured, says Reynolds, to be a "safe place" where questions can freely be asked, allowing communication between players to develop from inchoate musings into meaningful, complex thought. And driving that evolution is the appeal to some sort of higher authority, whose identity remains deliberately vague.

"The issues underlying the 'Sanctuary' idea for me are: How do we ask the right questions, and to what authority do we address them?" says the composer. "The search for an acceptable and useful authority is an important contemporary issue."

Sanctuary, by Roger Reynolds, will have its world premiere, performed by the ensemble red fish blue fish, in the Atrium of the East Building of the National Gallery of Art tonight at 6:30, preceded by a talk by the composer.

For more on Sanctuary, click here. To see videos of parts of the work, click here. For Roger Reynolds' website, click here. For more on Steven Schick, click here. To read Andrew Lindemann Malone's interview with Steve Antosca of the Contemporary Music Forum, click here.

Paul Badura-Skoda at the National Gallery

By Stephen Brookes

The Washington Post • November 13, 2007

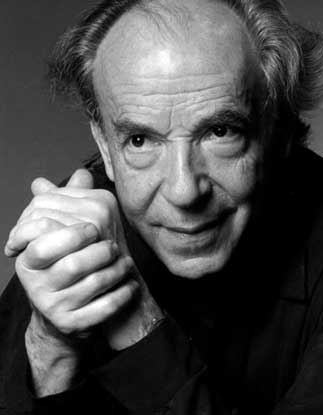

Paul Badura-Skoda

The legendary Austrian pianist Paul Badura-Skoda celebrated his 80th birthday last month, and after a lifetime of gold-standard performances, he'd be forgiven for resting on his considerable laurels. But in a bravura performance Sunday at the National Gallery of Art's West Garden Court, Badura-Skoda seemed to shrug off the decades, playing with power, remarkable fluidity and the unerring musicianship for which he's become famous.

A last-minute change in the program disappointed some listeners, who were looking forward to hearing two works by Schubert, whom the pianist has a particular affinity for. And the opening piece, Haydn's Sonata in A-flat, was a bit of a letdown with its a wooden Adagio and a finale that melted into mush in the venue's notorious acoustics.

But Badura-Skoda quickly turned things around in Beethoven's Sonata No. 21 in C (the "Waldstein"), which he played at the gallery in 1998. It's a work of almost triumphal exuberance, and the pianist brought it off with near-total command; a riveting, even exalting performance with little apparent loss of technique or energy over the past decade. Schumann's virtuosic, wonderfully variegated "Symphonic Etudes in the Form of Variations," Op. 13, was equally impressive.

The most interesting part of the program, though, came in the elegantly brooding "Fantasy on Flamenco Rhythms," a late work by the shamefully little-heard Swiss composer Frank Martin. Written specifically for Badura-Skoda, it filters the traditional rhythms and elemental spirit of flamenco through a sophisticated and thoroughly modern mind. Badura-Skoda played it with authority -- and a kind of quiet, smoldering passion.

Eartha Kitt at the Warner

By Stephen Brookes

The Washington Post • November 13, 2007

The great Eartha Kitt: still purring Is any woman on the planet more dangerous than Eartha Kitt? Even at 80, the original sex kitten can wreak more damage on men's hearts with a simple glance than today's pop tarts can with their entire bodies. And in a funny, flirtatious, high-octane performance on Saturday night at the Warner Theater, she showed the world how to age -- not just gracefully, but magnificently.

"I may be 80," Kitt said midway through the evening. "But I'm still purring!" And purr she did, through more than two dozen of the songs that have made her an icon across a six-decade career. Flashing a pair of still-perfect legs -- and toying with a few helpless males in the audience -- she brought perfect comic timing to classics like "Speaking of Love" ("I could be passionate/If there were cash in it"), "Old Fashioned Girl," "C'est Si Bon" and, of course, her trademark "I Want to Be Evil."

Amazingly, Kitt's elegantly strange voice seems hardly to have aged at all. It's still supple and completely theatrical, sliding effortlessly from sultry growl to coquettish whisper to full-blown roar. But Kitt didn't just sing onstage -- she lived the songs, strutting and kicking and slinking her way through the evening, sometimes just letting her hips do the talking.

And while most of the show was playfully tongue-in-cheek, Kitt showed her deeper side, too, bringing real heartbreak and despair to songs like "Guess Who I Saw Today" and "If You Go Away" (the Jacques Brel song also known as "Ne Me Quitte Pas").

Kitt got fine backup from her band, led by long-time music director Daryl Waters at the piano, with Brian Grice on drums, Lucio Hopper on bass, Joe Friedman on guitar and Carlos Gomez on percussion.

Zappa Redux, at the Warner

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • November 10, 2007

___________________________________________________________________________

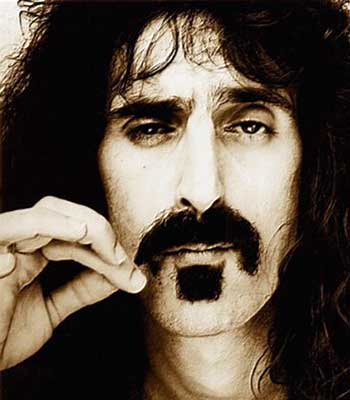

The late, great, Frank ZappaThe death of Frank Zappa in 1993 (at the absurdly young age of 52) left a hole that few other musicians would even try to fill. Composer, satirist, relentless rattler of cages, Zappa waged all-out musical war on the banality of modern life, releasing some 60 albums that ranged from rock to doo-wop to complex instrumentals influenced by Bartok and Stravinsky. And when he died, so did one of the most inventive, subversive and uninhibited musical imaginations on the planet.

Or at least, until now. Zappa’s son Dweezil, 38, an actor and accomplished guitarist in his own right, has been reviving his father’s music with a new production called “Zappa Plays Zappa”, which he brought to the Warner Theater on Wednesday night. It’s clearly a labor of love; for close to three hours, the younger Zappa led his seven-piece band on a fast-paced tour of the Zappa legacy, including classics like “Carolina Hard-Core Ecstasy,” “Pygmy Twylyte,” and “Brown Shoes Don’t Make It.”

It’s all music of ferocious complexity, lurching between styles, shifting meters on a dime and spitting out whatever was hurtling through the composer’s mind at the moment. But Dweezil has clearly done his homework; the entire band (which included Ray White, a guitarist and singer who toured with Zappa) brought the music off with painstaking professionalism and often note-for-note accuracy. Maybe it didn’t have the wild edginess of Zappa’s own performances, but that’s to be expected; the biting lyrics of thirty years ago sound a little dated today, and Dweezil, for all his gifts, didn’t really inherit his father’s live-wire persona.

But as a tribute, this was probably as good as it gets. Dweezil displayed some spectacular guitar chops, but kept the focus on his father – even wearing a Frank Zappa t-shirt throughout the performance. And one of the high points came early on, when Dweezil launched into the signature song “Cosmik Debris.” A video of his father materialized above the stage, and for the next ten minutes the two traded solos and seemed to beam at each other across time; a moving, if slightly eerie, father and son moment.