Paint Takes on Mozart, and Both Lose

The Washington Post 4/10/06: On paper, it sounds very cool: take a young avant-garde Austrian musician, add a few supporting players (including the son of one of the 20th Century’s most distinguished composers), and set them loose to rethink the music of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. That was the premise Friday night at the Embassy of Austria, where guitarist Martin Philadelphy and his free-improvising group Paint promised “some pictures of Mozart’s spirit and his art.”

Great idea, and kudos to the embassy for trying a fresh approach to this year-long celebration of Mozart’s birth. Unfortunately, Paint didn’t make much of the opportunity, serving up a muddled dog’s breakfast of avant-garde cliches, airless space-rock and good old-fashioned noodling. The Mozart connection was just a thin conceit -- and the promise of Eine Kleine Freimusik evaporated pretty quickly.

Great idea, and kudos to the embassy for trying a fresh approach to this year-long celebration of Mozart’s birth. Unfortunately, Paint didn’t make much of the opportunity, serving up a muddled dog’s breakfast of avant-garde cliches, airless space-rock and good old-fashioned noodling. The Mozart connection was just a thin conceit -- and the promise of Eine Kleine Freimusik evaporated pretty quickly.

Too bad; players like Henry Kaiser and John Zorn have shown that free improvising can produce some of the most intensely exciting, sophisticated and brainy music around. But it demands exceptional focus and musicianship, and Paint seemed content just to cook up undifferentiated masses of sound, letting them drift around aimlessly before they expired from sheer boredom.

Some of the few interesting moments of the evening came from percussionist Lukas Ligeti, who brought kinetic energy to the ensemble, and Marty McCavitt, who used a Mac sound processor and an antique zither to create detailed percussive effects and inject some actual Mozart into the mix. Tom Abbs mauled his cello, but otherwise did a nice job on bass. And while guitarist Philadelphy desperately needed an energy infusion, it hardly mattered – his amp was turned so low you could barely hear him over the fray.

Yo-Yo Ma at the Kennedy Center

By Stephen Brookes

The Washington Post 4/6/06

Is any performance as intimate as the solo recital? There’s nothing between the artist and audience -- no cloaking orchestra, no partner to play off, no accompanist to pick up the slack. Every thought is revealed with merciless clarity, setting the stage either for disaster – or for profound and illuminating communion.

And that’s exactly what cellist Yo-Yo Ma brought to the Kennedy Center on Tuesday night, in a transcendent performance of three of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Suites for Unaccompanied Cello. It may have been the ideal union between brilliant conception and stunning execution; with their austere architecture and limitless depths, the Bach suites feel as if they move with the weight and power of the galaxies. And in Ma’s hands they unfolded with sublime naturalness and grace – majestically revealed, rather than skillfully performed.

And that’s exactly what cellist Yo-Yo Ma brought to the Kennedy Center on Tuesday night, in a transcendent performance of three of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Suites for Unaccompanied Cello. It may have been the ideal union between brilliant conception and stunning execution; with their austere architecture and limitless depths, the Bach suites feel as if they move with the weight and power of the galaxies. And in Ma’s hands they unfolded with sublime naturalness and grace – majestically revealed, rather than skillfully performed.

The evening opened with the Suite No. 3 in C Major. Relatively the sunniest of the suites, it’s a strong but wonderfully lyrical work. Using bare-bones rubato and minimal ornamentation, Ma infused the dance movements with light, and brought out the intensity and thought that lie at their heart. That was followed with the much darker Suite No. 5 in C Minor. Ma played it with restrained passion, and it took on a meditative presence that suffused the hall.

But the climax of the evening was his radiant, Apollonian reading of the Suite No. 6 in D Major. There’s a sense of vastness about this work, like the inside of a cathedral. Ma not only captured that vastness – he filled it with almost infinite humanity and grace.

Yundi Li: the Piano Showdown Begins

The Washington Post 4/03/06: Is the Music Center at Strathmore trying to start a fight? That’s the only logical explanation for scheduling Yundi Li and Lang Lang – the two dueling Chinese enfants terribles of the piano world – virtually back to back this month, with suspiciously similar programs of Mozart, Schumann and Liszt. Why not just put a boxing ring on stage and have at it?

At any rate, Yundi Li got in some solid punches on Saturday night, displaying the intelligence, taste and nosebleed-altitude virtuosity he’s become famous for. Admittedly, things got off to a wobbly start with Mozart’s piano sonata in C (K. 330), which in the right hands crackles with brainy wit. Li gave it a more relaxed reading that was pretty – even sensual – rather than incisive, and failed to engage too many brain cells.

At any rate, Yundi Li got in some solid punches on Saturday night, displaying the intelligence, taste and nosebleed-altitude virtuosity he’s become famous for. Admittedly, things got off to a wobbly start with Mozart’s piano sonata in C (K. 330), which in the right hands crackles with brainy wit. Li gave it a more relaxed reading that was pretty – even sensual – rather than incisive, and failed to engage too many brain cells.

But his account of Robert Schumann’s Carnaval, Op. 9 was far more impressive. Li brings fresh insight to the romantics, and he explored the Schumann as if he were discovering it for the first time. Nuanced, thoughtful, elegant and alive, it also gave Li a chance to display his celebrated limpid fingering, precise dynamic control, and ear-melting tone.

Nevertheless, it was only in the final work – Franz Liszt’s tempestuous and demonic Sonata in B Minor – that Li really demonstrated why he’s already in the top ranks of the world’s pianists. He gave a remarkable interpretation of this behemoth, both rigorously coherent and unrelentingly powerful, breathing white-hot fury and ethereal calm – a knockout performance by any standard. When Lang Lang takes the stage on April 13, he’ll have his work cut out for him.

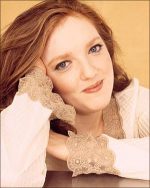

Rachel Barton Pine Unleashed at the National Gallery

The Washington Post 3/28/06: Imagination, panache, note-perfect virtuosity – it’s not hard to see why Rachel Barton Pine is one of the rising stars of the violin world. She’s an exciting and boundary-defying performer, soloing in the Brahms Concerto one day, jamming with members of Black Sabbath the next. And in an adventurous, virtually flawless performance Sunday night at the National Gallery of Art (with the talented Matthew Hagle at the piano), Pine showed she’s a major talent to reckon with.

The program opened with Heinrich von Biber’s Passacaglia in G Minor for unaccompanied violin – a dark, magnificent and austere work, to which Pine brought profound dignity and insight. She then jumped into much lighter fare – Fritz Kreisler’s romping arrangement of the Mozart Rondo in D major (K. 382). Two parts Kreisler to one part Mozart, the arrangement is a wild and rambunctious ride, and Pine took it to all its delirious heights without ever careening over the top.

The program opened with Heinrich von Biber’s Passacaglia in G Minor for unaccompanied violin – a dark, magnificent and austere work, to which Pine brought profound dignity and insight. She then jumped into much lighter fare – Fritz Kreisler’s romping arrangement of the Mozart Rondo in D major (K. 382). Two parts Kreisler to one part Mozart, the arrangement is a wild and rambunctious ride, and Pine took it to all its delirious heights without ever careening over the top.

That was followed by Robert Schumann’s Sonata No. 1 in A Minor, a work that both simmers with explosive power and shimmers with delicacy. Pine handled every nuance with soul and brains, delivering a hot-blooded performance that would have made Schumann himself swoon.

The second half of the program was devoted to American music, with Coleridge Taylor Perkinson’s Blue/s Forms and an enjoyable suite of fiddle-tunes by Marc O’Connor. But the highlight of the evening was John Corigliano’s prize-winning 1963 Sonata for Violin and Piano. Far too rarely heard, the sonata is a tour de force for the violin, and in Pine’s hands it surged to life – a complex and infinitely fascinating work, whose Andantino contains some of the loveliest and most delicate music written in the last half-century.

Download the Rachel Barton Pine pdf.

Bach Collegium Japan at the Library of Congress

The Washington Post 3/27/07: If there are any doubts that the Bach Collegium Japan is one of the most astonishing baroque ensembles on the planet, they were dispelled Friday night in a performance at the Library of Congress that was so beautiful, so riveting, so ferociously intense in every way, that Coolige Auditorium may never be the same.

Johann Sebastian BachThe Collegium specializes in authentic performance of baroque music, using the period instruments and techniques that have become virtually standard -- and often fussily academic -- in concert halls everywhere. But there was nothing stuffy about Friday’s performance. Harpsichordist and artistic director Masaaki Suzuki brought such penetrating focus to this sound that every shred of affect was burned away – leaving nothing but pure music in its wake.

And what music! The all-Bach evening opened with the Orchestral Suite no. 2 in B minor, a lyrical and wonderfully inventive set of dances. Pixie-esque flutist Liliko Maeda turned in a bravura performance on the one-keyed wooden flute – perhaps the prettiest and most unforgiving instrument known to man – negotiating the finger-snarling passagework with spirit and enviable nonchalance.

That was followed by the searing Harpsichord Concerto no. 1 in D minor, one of Bach’s darkest and most moving works. The harpsichord can be hard to love -- Sir Thomas Beecham compared it to “two skeletons copulating on a tin roof” -- but in Suzuki’s hands it became an instrument of transfiguring power, with a virtuosic and unrelenting performance that cut straight to the heart.

Masaaki Suzuki at the keyboardThat was hard to top, but Ryo Terakado and Natsumi Wakamatsu tried, and their reading of the Concerto for Two Violins in D minor was so fiery and intense that ears were melting throughout the hall. Unforgettable performances, topped off with an account of the Brandenburg Concerto no. 5 that, like everything else on the program, raised the bar on Bach performance to new and spectacular heights.

Ned Rothenberg: Forays into the Sonic Unknown

The Washington Post 3/26/06: Ned Rothenberg has long been one of the most inventive and consistently satisfying performer/composers on the New York new music scene, always exploring the edges (who else plays the Japanese shakuhachi in jazz?) and embarking on strange, evocative and ear-bending forays into the sonic unknown.

On Saturday night he brought his intriguing trio, Sync – with Samir Chatterjee on tablas and Jerome Harris on acoustic guitars -- to Takoma Park’s Sangha performance space. Rothenberg himself is a virtuosic winds player with a wide palette of multiphonics, circular breathing and other advanced techniques, all in service to one of the most distinctive musical imaginations around.

On Saturday night he brought his intriguing trio, Sync – with Samir Chatterjee on tablas and Jerome Harris on acoustic guitars -- to Takoma Park’s Sangha performance space. Rothenberg himself is a virtuosic winds player with a wide palette of multiphonics, circular breathing and other advanced techniques, all in service to one of the most distinctive musical imaginations around.

And the music – drawn from the trio’s two recordings, Port of Entry and Harbinger – was flat-out gorgeous, with a warmth not always found in contemporary music. Playing everything from alto sax to bass clarinet, Rothenberg launched adventurous, intricate solos that unfolded effortlessly through smoky blues and otherworldly squawks to intimate modal ruminations. His sense of line and drama is impeccable, and over Chatterjee’s roiling tabla-work and Harris’ introspective guitar lines, the effect was compelling.

At first glance, this variation on the standard drums/bass/winds set-up looks strained, like a blind date among world music idioms. And learned scholars may debate whether shakuhachi, brushed tablas and slide bass guitar will ever really click together. But this is unusually thoughtful music, and the subtleties of the tabla, along with Harris’ sinuous guitar work, beautifully complemented Rothenberg’s detailed, colorful and hyper-imaginative playing. Download the Rothenberg pdf

Eclipse Chamber Orchestra at Schlesinger

The Washington Post 3/21/06: The 250th anniversary of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s birthday continues with no end, thank goodness, in immediate sight. And on Sunday at the Rachel M. Schlesinger Concert Hall, Washington’s superb Eclipse Chamber Orchestra added some intriguing historical perspective to the ongoing celebration.

Sylvia AlimenaIn a program titled “1756: It Was A Very Good Year”, ECO music director Sylvia Alimena explored a simple idea: take the music being written at the time of Mozart’s birth and compare it with one of his fully mature works. Those three decades, of course, marked an almost violent transition from the Baroque, through the Mannheim School of Johann Stamitz, to the first glimpses of Romantic sensibility that can be seen in Mozart’s own remarkable Symphony No. 40 in g minor (K. 550) written in 1788.

Alimena set off on this journey with George Frideric Handel’s Overture to Judas Maccabeus – a bit dusty and musty after two and a half centuries, but brought to life in a clear and compelling reading by the ECO. That was followed by some pleasant musical wallpaper by Florian Leopold Gassmann (a mostly-forgotten 18th Century composer of opera buffa) and the more engaging Sinfonia Op. 3, No. 6 by Stamitz, a composer whose influence on symphonic form (and hence on Mozart) was immense.

Enjoyable music, deftly played. Yet the works paled to nothing beside Mozart’s great and tragic Symphony #40, which made up the second half of the program. For Alimena, it’s virtually a Romantic work, and she brought out its pathos in a beautiful, even electrifying interpretation -- a performance that only underscored how fresh and powerful Mozart continues to sound, while most of his contemporaries must settle for mere historical context.