Sarabande and Arcovoce at the Church of the Epiphany

By Stephen Brookes • The Washingotn Post • June 23, 2014

There may be few kinds of music as immediately likable as Baroque chamber music, which is usually heard on modern instruments. But its subtle beauties are better revealed by the delicate, soft-voiced instruments of the time, as was clear at Sunday’s Baroque Bonanza concert at the Church of the Epiphany, when two of the most gifted Baroque ensembles in the area joined forces for an afternoon of music making that captured the vitality of this music as well as its subtle nuances. Rosa LamoreauxThe unusual ensemble Sarabande (named for the several Sarahs who founded it) opened the concert with music for baroque oboes, baroque bassoon and percussion. These double-reed instruments have a particularly throaty and arresting sound, and in a half-hour of short works by George Frideric Handel, Jean-Baptiste Lully, André Danican Philidor and others, the Sarabande players used the rich, plaintive timbres and flavorful intonations to highly expressive effect. Alison Lowell, Meg Owens and Sarah Weiner turned in fine playing on oboe, as did Stephanie Corwin on bassoon, while Michelle Humphreys — playing tambourine and drum with a light, sensitive touch — added a feathery texture to the music that enhanced the other instruments.

Rosa LamoreauxThe unusual ensemble Sarabande (named for the several Sarahs who founded it) opened the concert with music for baroque oboes, baroque bassoon and percussion. These double-reed instruments have a particularly throaty and arresting sound, and in a half-hour of short works by George Frideric Handel, Jean-Baptiste Lully, André Danican Philidor and others, the Sarabande players used the rich, plaintive timbres and flavorful intonations to highly expressive effect. Alison Lowell, Meg Owens and Sarah Weiner turned in fine playing on oboe, as did Stephanie Corwin on bassoon, while Michelle Humphreys — playing tambourine and drum with a light, sensitive touch — added a feathery texture to the music that enhanced the other instruments.

Rosa Lamoreaux is one of the finest early-music sopranos to be found, and she opened the second half of the program by leading the Arcovoce ensemble in strikingly vivid readings of two chamber cantatas, Vivaldi’s “All’ombra di sospetto” and Alessandro Scarlatti’s “Correa nel seno.” The instrumentalists in this remarkable ensemble are equally strong, and Nina Falk (on baroque violin) turned in a mesmerizing account of the Sonata No. 3 in F major by Elisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre (one of the rare female composers of the time), while harpsichordist Stephen Silverman played two of Domenico Scarlatti’s sonatas with rare insight and grace.

June Chamber Festival at the Kreeger Museum

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • June 15, 2014

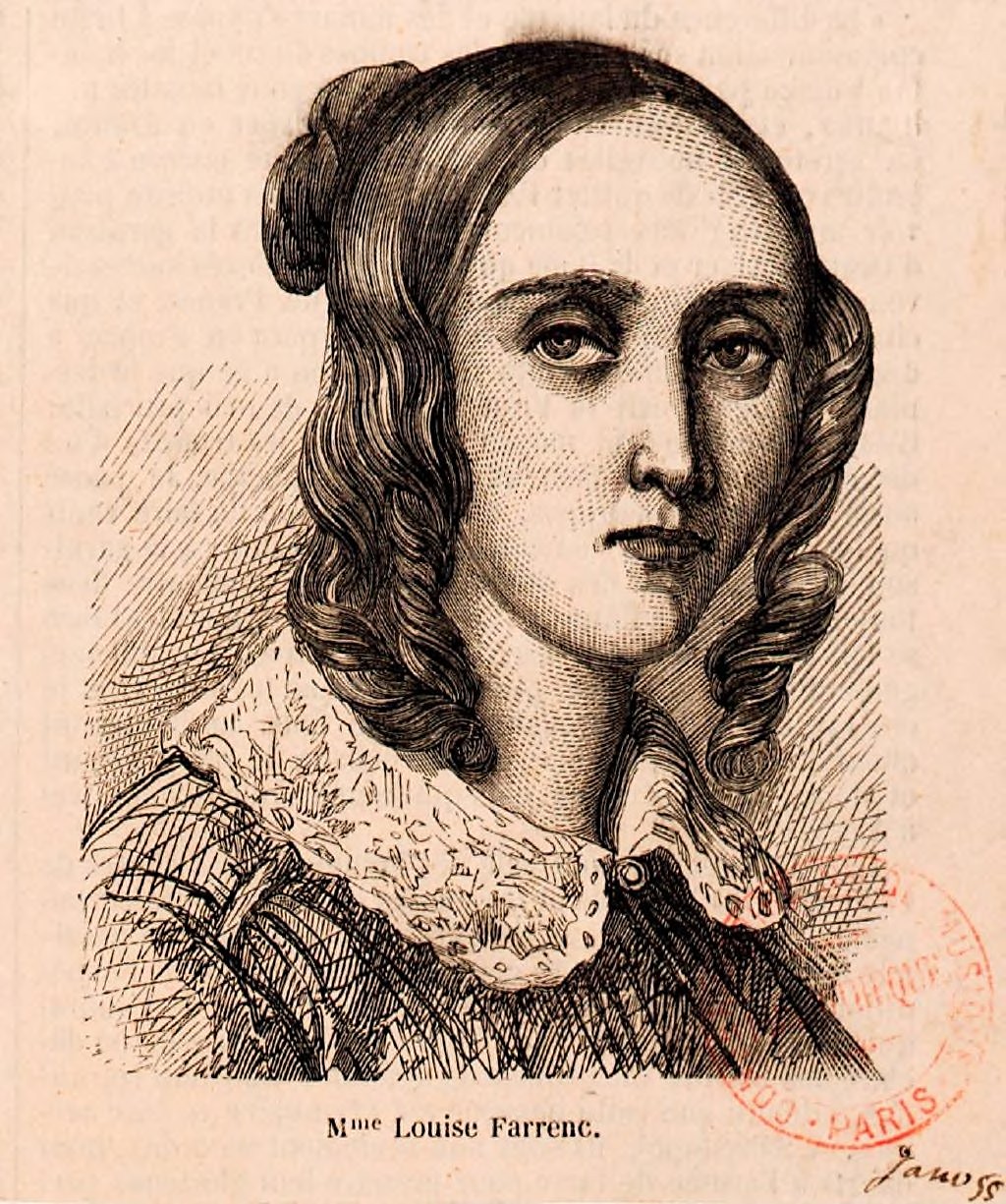

Rummage around in classical music’s closets, and you’re bound to find a few treasures: works by once-famous composers who have long vanished from view. Take Louise Farrenc, for instance. This 19th-century French composer rose to prominence in the male-dominated musical establishment of her time, was promptly forgotten, and left behind some superb music, including the rarely heard “Trio for flute, cello, and piano, Op. 45,” the highlight of a fine concert by the American Chamber Players at the Kreeger Museum on Friday evening. The concert marked the opening of the Kreeger’s annual June Chamber Festival, which for 10 years — under the imaginative direction of violist Miles Hoffman — has showcased some of the area’s best musicians in an acoustically near-perfect setting. Hoffman got a shock a couple of weeks ago when scheduled pianist Anna Stoytcheva was suddenly called out of town, but Lisa Emenheiser (well known to D.C. audiences for her work with the National Symphony Orchestra) heroically stepped in, mastering a range of new works in a matter of days. It took Emenheiser a minute or two to settle into the opening work, Mozart’s Piano Quartet in E-flat Major, K. 483 — a piece balanced delicately between a concerto and a string quartet — but by the middle of the Larghetto she fully owned the music and turned in thoughtful, accomplished playing all evening.

The concert marked the opening of the Kreeger’s annual June Chamber Festival, which for 10 years — under the imaginative direction of violist Miles Hoffman — has showcased some of the area’s best musicians in an acoustically near-perfect setting. Hoffman got a shock a couple of weeks ago when scheduled pianist Anna Stoytcheva was suddenly called out of town, but Lisa Emenheiser (well known to D.C. audiences for her work with the National Symphony Orchestra) heroically stepped in, mastering a range of new works in a matter of days. It took Emenheiser a minute or two to settle into the opening work, Mozart’s Piano Quartet in E-flat Major, K. 483 — a piece balanced delicately between a concerto and a string quartet — but by the middle of the Larghetto she fully owned the music and turned in thoughtful, accomplished playing all evening.

Violinist Joanna Maurer’s probing, fiercely intelligent playing (particularly in 20th-century music) has always been a high point of this festival, and she joined cellist Stephen Balderston for Bohuslav Martinu’s 1927 “Duo No. 1 for violin and cello.” Its two contrasting movements pit brooding lyricism against the propulsive rhythms of Czech folk music, and the players — sharing a clear rapport — turned in a riveting, virtuosic reading.

The four “fairy-tale pictures” of Schumann’s “Märchenbilder for Viola and Piano, Opus 113” range from robust to melancholy, and gave Hoffman a chance to display his extroverted playing. But the most intriguing — and certainly charming — work of the evening may have been Farrenc’s Trio. This 1857 work is written with a lilting, lyrical touch, and flutist Sara Stern led the ensemble in a reading steeped in romanticism and elegant drama.

The Kreeger festival continues on Tuesday and Friday, with music by Brahms, Bruch, Raimi, Mozart and others.

Gilles Vonsattel at the National Gallery of Art

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • June 6, 2014

Linking a concert to an art exhibit can be illuminating: Find the connections between composers and painters of a particular era, and you often discover something new about both. That was the premise behind Thursday night’s concert at the Freer Gallery, when the pianist Gilles Vonsattel performed music by Western composers that would have been performed in late 19th-century Japan, when the artist Kobayashi Kiyochika was creating a series of woodblock prints now on exhibit at the Freer. The connection may have been a bit thin, but in the end, it didn’t matter. Vonsattel chose such a thoughtful and tightly knit program, so rich in internal musical references, shared themes and surprising cross-connections, that any link to Japanese art seemed almost incidental. Gilles VondsattelThe Kiyochika exhibit is titled “Master of the Night,” and Vonsattel chose a suitably dark program with Beethoven at its heart. After tossing off the six Bagatelles, Op. 126, he moved into the more complex waters of the Sonata in C-sharp Minor, Op 27 No. 2 — better known as the “Moonlight.” Its famous first movement has suffered no end of sappy interpretations, but Vonsattel brought out a more probing, somber, even funereal side in a performance that was often spellbinding. The second movement was oddly polite, and the final movement might have used a little more wild-eyed ferocity. But you got the sense that Vonsattel is more interested in ideas than in stormy passion, and more power to him: This is a thinking person’s pianist.

Gilles VondsattelThe Kiyochika exhibit is titled “Master of the Night,” and Vonsattel chose a suitably dark program with Beethoven at its heart. After tossing off the six Bagatelles, Op. 126, he moved into the more complex waters of the Sonata in C-sharp Minor, Op 27 No. 2 — better known as the “Moonlight.” Its famous first movement has suffered no end of sappy interpretations, but Vonsattel brought out a more probing, somber, even funereal side in a performance that was often spellbinding. The second movement was oddly polite, and the final movement might have used a little more wild-eyed ferocity. But you got the sense that Vonsattel is more interested in ideas than in stormy passion, and more power to him: This is a thinking person’s pianist.

The darkness got even darker in Liszt’s wonderfully morbid “Pensee des Morts” (from Harmonies Poetiques et Religieuses, S. 173). Sounding of tolling funeral bells, and so closely tied to the Beethoven sonata that it even quotes it, the work is a brooding meditation on death, and it was fascinating to hear it between the Beethoven and Olivier Messiaen’s “Cloches d’angoisse et larmes d’adieu (Bells of Anguish and Tears of Farewell)” — a work of palpable spirituality, full of far more hope and celestial light than the title might suggest.

Schumann’s Arabeske in C, Op. 18, provided a pleasant interlude, followed by six pieces from Debussy’s two books of “Images” — chosen, perhaps, to echo the bells (“Cloches a travers les feuilles”) of the Liszt and the impressions of water (“Reflets dans l’eau”) and moonlight (“Et la lune descend sur le temple qui fut”) that have long been associated with the “Moonlight” sonata. Vonsattel took a refreshingly full-blooded approach to the works, delicate and precise but without the relentless shimmer that can make Debussy seem gauzy, and he closed (extending the water theme even further) with Liszt’s “Les jeux d’eau a la Villa d’Este.”

Emmanuel Ceysson at the National Gallery of Art

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • June 2, 2014

Remember those idyllic days of fin-de-siècle France, when life was an endless pique-nique in a sunlit field of flowers? No? Neither do I. But on Sunday evening at the National Gallery of Art, the virtuosic harpist Emmanuel Ceysson presented a program of French music from the late 19th and early 20th centuries that evoked a world of distant, shimmering beauty — a last gasp of innocence before modernism crashed the party — that dovetailed with the Gallery’s ongoing “Degas/Cassat” exhibit. Emmanuel CeyssonCeysson is a rising star in the harp world, and from the opening “Impromptu-Caprice” by Gabriel Pierné, it was clear that both his technique and his musicianship are virtually flawless. The harp may seem ethereal, but it’s capable of an almost orchestral richness of sound, and the first half of the program — romantic, ultra-refined showpieces from such early harpist-composers as Albert Zabel, Alphonse Hasselmans and Henriette Renié — allowed Ceysson to display a vast arsenal of coloristic techniques.

Emmanuel CeyssonCeysson is a rising star in the harp world, and from the opening “Impromptu-Caprice” by Gabriel Pierné, it was clear that both his technique and his musicianship are virtually flawless. The harp may seem ethereal, but it’s capable of an almost orchestral richness of sound, and the first half of the program — romantic, ultra-refined showpieces from such early harpist-composers as Albert Zabel, Alphonse Hasselmans and Henriette Renié — allowed Ceysson to display a vast arsenal of coloristic techniques.

But beyond the sweeping glissandi and diaphanous, perfectly-plucked passages, it was Ceysson’s musical intelligence that really impressed. He imbued Renié’s “Légende” with an otherworldly light, and the many levels of Hasselmans’s “La Source” seemed to float against each other with weightless transparency. Even Zabel’s rather stagy “Faust Fantasie” came off with convincing style.

It was the impressionist-era works in the second half of the program, though, that revealed Ceysson’s more substantial depths. He played the Debussy preludes “La fille aux cheveux de lin” and “Bruyères” with a delicacy almost impossible to achieve on the piano, and two clever, richly imaginative Divertimentos by André Caplet were a delight to hear. Marcel Tournier’s gentle, pastoral “Vers la source dans le bois” gave the impression of being awash in dappled sunlight.

The high point, though, may have been Gabriel Fauré’s “Une châtelaine en sa tour, op. 110,” a rich and emotionally complex work that Ceysson played to near perfection. Oddly, he seemed a little less comfortable in his own composition, “Paraphrase sur Carmen de Georges Bizet,” which had a few wooden moments. But it was an impressive and deeply involving evening all in all, and a wildly enthusiastic ovation brought Ceysson back for an encore: “Colorado Trail” by Marcel Grandjany, another French harpist-composer.

Arvo Pärt at the Phillips Collection

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • May 30, 2014

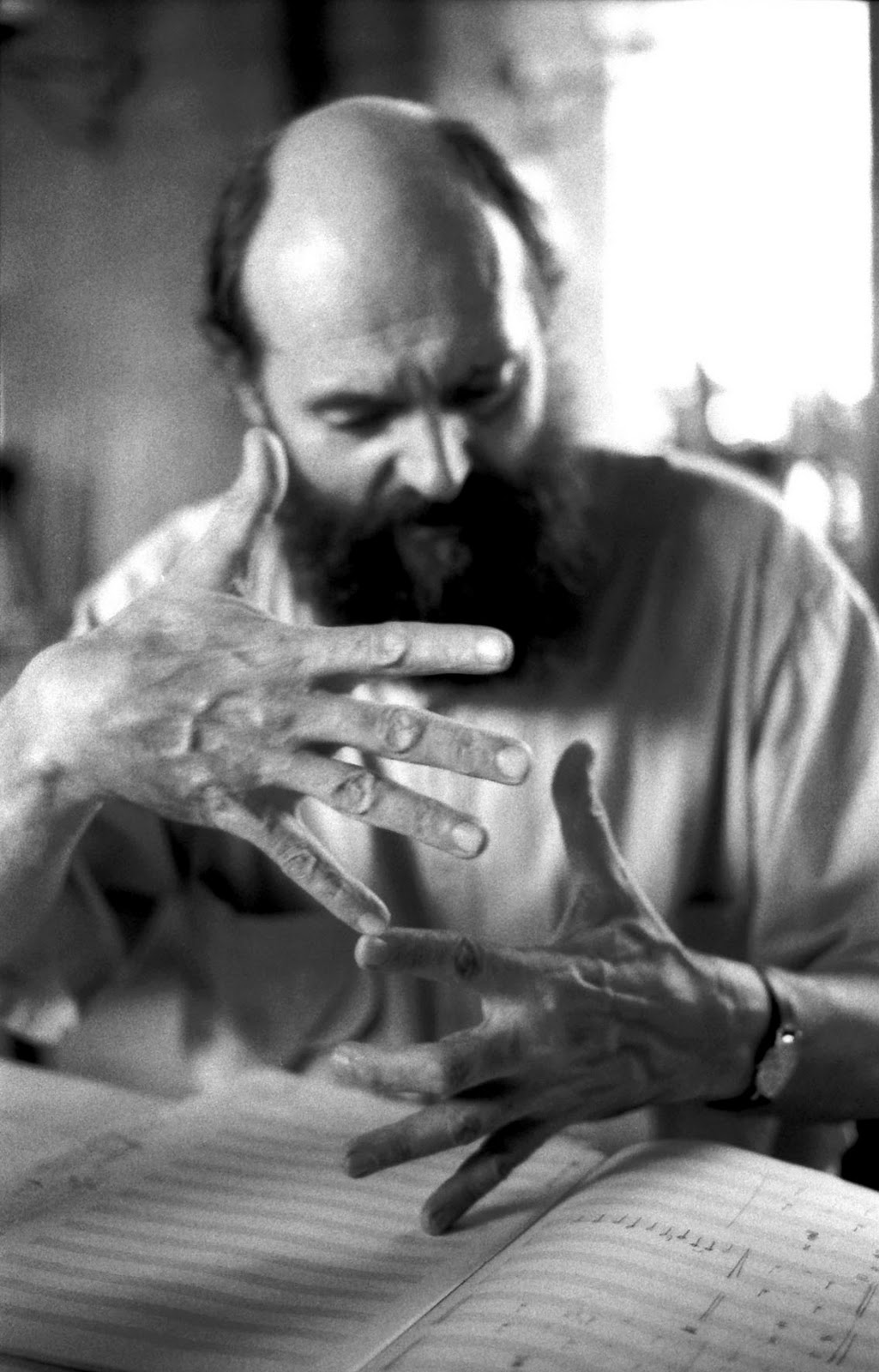

The remarkable Estonian composer Arvo Pärt — whose spare and almost mystical music has been embraced by an audience far beyond the usual classical circles — has had a triumphant run in Washington this week. After a hugely successful concert of orchestral and choral works at the Kennedy Center on Tuesday, Pärt returned on Thursday to the Phillips Collection for a more intimate performance of his chamber music — nearly a dozen works that, despite their modest size, seemed to evoke the same aura of quiet majesty, the same sense of austere spirituality, and the same purity of expression as his large-scale music. Arvo PärtThat’s no easy task. But as the evening unfolded — sketching an arc from the pathbreaking “Für Alina” from 1976, to the premiere of his newest work, “My Heart’s in the Highlands” — it was clear that Pärt’s music thrives on being pared to its essentials, becoming all the more powerful for it. Pärt is often labeled (by admirers and detractors alike) as a “holy minimalist,” but it’s an apt title. In “Für Alina,” for example, he built a sense of limitless, light-filled space with only the simplest of musical materials, and in every work on the program he seemed to find a universe in even the smallest grain of musical sand.

Arvo PärtThat’s no easy task. But as the evening unfolded — sketching an arc from the pathbreaking “Für Alina” from 1976, to the premiere of his newest work, “My Heart’s in the Highlands” — it was clear that Pärt’s music thrives on being pared to its essentials, becoming all the more powerful for it. Pärt is often labeled (by admirers and detractors alike) as a “holy minimalist,” but it’s an apt title. In “Für Alina,” for example, he built a sense of limitless, light-filled space with only the simplest of musical materials, and in every work on the program he seemed to find a universe in even the smallest grain of musical sand.

That held true throughout the evening, from the tender “Variations for the Healing of Arinushka” (in a deeply felt reading by pianist Marrit Gerretz-Traksmann) to the radiant “Vater unser,” sung by alto Iris Oja. There were a few familiar works, including “Spiegel im Spiegel” (now so iconic it’s even been quoted in “The Simpsons”) and “Fratres” (heard here for violin and piano, in contrast to the orchestral version at the Kennedy Center), but less-familiar pieces such as “Mozart-Adagio” — a stunning arrangement of the second movement of Mozart’s piano sonata in F Major, K. 280 — and the relatively dark and dissonant “Es sang vor langen jahren,” showed off aspects of Pärt’s musical personality that only deepened the interest of his music.

Stefan Jackiw and Anna Polansky at the Terrace Theater

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • May 22, 2014

So maybe Mozart’s violin sonatas aren’t the absolute peak of his musical achievements — they’re still hugely enjoyable works, particularly when played with the warmth and easy naturalness that violinist Stefan Jackiw brought to the Sonata in B-flat, K. 378 on Wednesday night at the Kennedy Center’s Terrace Theater. The 29-year-old Jackiw has everything you expect in a rising star — nimble technique, expressive tone, thoughtful interpretation — but his Mozart had a rare and wonderful sense of intimacy as well, as if he were having a private conversation with pianist Anna Polonsky, and we in the audience were just listening in. For all the charm of the Mozart, though, the real heart of the evening (part of Washington Performing Arts Society’s “Virtuoso Series”) came in Witold Lutoslawski’s “Partita for Violin and Piano” from 1984, a work so explosive that the word “volcanic” barely covers it. Darkly lyrical, wildly atmospheric, it built to such white-hot intensity in the central Largo (aptly described by Jackiw as “an apocalyptic meditation”) that you thought the violin would erupt in flames. Jackiw threw himself into the music as if nothing else mattered and turned in the kind of playing you always hope for at a concert but rarely hear. It was an absolutely spectacular performance, run through with urgent and often unsettling beauty.

For all the charm of the Mozart, though, the real heart of the evening (part of Washington Performing Arts Society’s “Virtuoso Series”) came in Witold Lutoslawski’s “Partita for Violin and Piano” from 1984, a work so explosive that the word “volcanic” barely covers it. Darkly lyrical, wildly atmospheric, it built to such white-hot intensity in the central Largo (aptly described by Jackiw as “an apocalyptic meditation”) that you thought the violin would erupt in flames. Jackiw threw himself into the music as if nothing else mattered and turned in the kind of playing you always hope for at a concert but rarely hear. It was an absolutely spectacular performance, run through with urgent and often unsettling beauty.

When Lutoslawski passed away in 1994, the Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho wrote a tender “Nocturne” for solo violin in his memory. It’s a haunting piece sketched in shadowy wisps of sound, and Jackiw used it as a deft transition to Brahms’s Violin Sonata No. 3 in D minor, Op. 108. Brahms can give a glowing finish to just about any concert, and this particular work radiates so much light and life and joyful optimism that it’s impossible not to be swept away by it — especially in Jackiw and Polonsky’s expressive, elegantly polished reading.

Martin Helmchen at the Terrace Theater

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • May 11, 2014

The world isn’t exactly short of brilliant concert pianists — it’s sometimes hard to turn around without knocking one over — but Martin Helmchen stands out even in that remarkable crowd. Still in his early 30s, Helmchen has been winning praise in Europe for his high-powered performances, and his effortless virtuosity was abundantly on display at the Terrace Theater on Saturday, where he performed as part of the Hayes Piano Series of the Washington Performing Arts Society. But it wasn’t so much the young German’s technique — which truly is spectacular — that made the afternoon memorable as it was the distinctive poetic imagination that he brought to virtually everything he played.

Still in his early 30s, Helmchen has been winning praise in Europe for his high-powered performances, and his effortless virtuosity was abundantly on display at the Terrace Theater on Saturday, where he performed as part of the Hayes Piano Series of the Washington Performing Arts Society. But it wasn’t so much the young German’s technique — which truly is spectacular — that made the afternoon memorable as it was the distinctive poetic imagination that he brought to virtually everything he played.

The program itself didn’t veer too daringly from the beaten path: a mix of mainstream German and Austrian works, with Schubert’s great “Wanderer” Fantasy as the linchpin. But Helmchen seemed to find a sense of freshness and discovery in every work, from Bach’s Partita No. 4 in D Major, BWV 828 (in a magnificent, slightly chilled reading), to an exceptionally vivid and detailed account of Schumann’s Waldszenen, Op. 82. A collection of nine “forest scenes” that range from the simple melodies of “Einsame Blumen” (Solitary Flowers) to the feverishly colored “Vogel als Prophet” (The Prophet Bird), Waldszenen is Schumann at his most elusive and complex, and Helmchen turned in a subtle, and often enchanting, performance.

Schubert’s Fantasy in C Major, D. 760 was the climax of the program, and Helmchen gave it a big-boned, heroic performance that brought the audience to its feet. But the real surprise of the afternoon may have been Anton Webern’s Variations for piano, Op. 27. Webern’s often thought of as a cold-hearted serialist, smiling cruelly as he cuts his music to its bare essentials, but in Helmchen’s hands the Variations came to life, wonderfully warm and animated and even charming.

In all, a fascinating and deeply rewarding concert, which closed with a piano transcription of Bach’s serene and infinitely beautiful Chorale Prelude Ich ruf zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ (I), BWV 639.