guitar festival for gendai

THE SECOND IBERO-AMERICAN GUITAR FESTIVAL

OCT 20-23, 2008

By Stephen Brookes 703 660-6591

stephen.brookes@verizon.net

Washington, DC has been a center for international diplomacy for decades. But it’s also a growing center for cultural diplomacy, where a global exchange of ideas in art and music takes place. While there are frequent concerts and exhibitions at embassies around town, one of the most important and ambitious new events is the annual Ibero-American Guitar Festival – which puts a spotlight on the best of new guitar music from Latin America, Spain, and Portugal.

Sponsored by the Association of Ibero-American Cultural Attaches (with artistic direction by the well-known Paraguayan guitarist Berta Rojas), this year’s festival was held October 20-23, and brought 17 performers to the campus of George Washington University for four days of concerts and master classes. Some of Latin America’s most interesting rising young guitarists were present, and their concerts showed how rich and varied Latin music is today, in every genre from classical to flamenco and beyond.

“The guitar is the unifying instrument of Latin America,” says Magdalena Duhagon, a DC-based Uruguayan guitarist who is the assistant director of the festival. “Latin culture is very present in the guitar, and the repertoire is big. But audiences in the United States are not familiar with the repertoire – many are hearing it for the first time.”

The guitar, of course, is at the heart of Latin music. Many of Latin America’s best-known composers – Agustin Barrios Mangore, to name just one – were also accomplished guitarists, and the instrument is widely played in folk music across the continent. Its influence has been so profound that it’s hard to imagine Latin American music without the guitar.

But Latin guitar music is still largely unheard in North America. Composers such as Astor Piazzola and Leo Brouwer have become well known, but the festival gave audiences a chance to hear lesser-known guitarist-composers like Paulo Bellinati and Maximo Diego Pujol. The programs were adventurous, and many of the performers explored the connections between new Latin music and its roots, from the rhythms of Andalusia, to the timbres of Andean folk music and the song-like melodies of the Caribbean.

Most of the events of the festival were held in the Jack Morton Auditorium of George Washington University – an intimate venue with fine acoustics, dramatic lighting and seating limited to about 250, near perfect for guitar concerts. But the hallway outside was an equally interesting place to be, as it was set up with an exhibit on the life of the great Venezuelan guitar pioneer Alirio Diaz, who came to the festival for the first few days.

“Music is my life, and I’m so happy to be here to share it with you,” he said at the festival’s opening reception, as he spoke with fans, diplomats and friends. At 84, Diaz is still an active teacher and performer, and the exhibit testified to the impact of his life. Letters and photographs from his early years, when he studied with Andres Segovia, were mixed in with programs and concert posters from a spectacular career that took him to Paris, London, New York, Tokyo, Rome and beyond.

One admirer asked him how old he was when he first took up the guitar. “I don’t remember,” said Diaz, laughing. “I think I was born with a guitar in my hands.”

Diaz was an important influence on hundreds of his students – including Sharon Isbin, who was there to open the festival’s first night. Isbin, who heads Julliard’s guitar department, stuck largely to familiar Latin works, including Francisco Tarrega’s “Recuerdos de la Alhambra” and Leo Brouwer’s “The Black Decameron.” Isbin is a rather cerebral player, but her sophistication and genuine love of the music were clear, and her performance reached a peak when she was joined her onstage by Brta Rojas for Gentil Montana’s engaging “El Porro.”

It was an exciting start to the Festival, and more was to come. Four performers played each evening (with more concerts and master classes during the day), offering a mix of styles that changed from set to set. Nearly all the region’s countries were represented, with each performer displaying different sides of Ibero-American guitar culture.

Electric jazz-rocker Federico Miranda, for example, played sections of his “Baula Project” (focusing on endangered leatherback turtles in his native Costa Rica), while Uruguay’s Marco Sartor contrasted the baroque-flavored music of Domenico Scarlatti with composers like Abel Fleury, and Juan Falu – perhaps Argentina’s best-loved guitarist – provided his own signature brand of sophisticated folk music.

Edgy rock was provided by Ramses Barrientos -- a Honduran composer whose cherry-red electric guitar and glinting eyebrow ring immediately set him apart from the festival’s more traditional players , while Antonio Chaino (one of the masters of the Portuguese guitar, a round-body instrument with twelve steel strings and a short neck) pulled a quavering, almost voice-like tone out of the guitar – perfect for poignant works like “Sonhar Lisboa” and “Rhapsodia Fadista” that are rooted in the melancholy Portuguese folk music called fado.

Next came flamenco guitarist Abraham Carmona. Born into a gypsy family in Seville, Carmona has roots in tradition but is a modern internationalist, blending jazz, tango, bossa nova and even Asian elements into his playing. Opening with a few traditional bulerias (including “Mariposa” by Manuel Molina), he devoted most of the set to his with his own songs, joined later by the fine Argentinean bandoneon player Juan Pablo Jofre in music that summoned up sultry tangos in smoky, late night dance halls.

The next day opened with a midday concert of music from 17th century Bogotá by the Colombian group Musica Ficta, and some new Ecuadorian music played by guitarist Rene Zambrano. Despite a rather serious, stolid demeanor, Zambrano put on a very sensitive, lyrical performance of works like Carlos Silva’s Baroque-flavored “El Ultimo Beso,” and several pieces by Carlos Bonilla, including the beautiful and quietly dramatic “Preludio y Yumbo.”

That was followed by music from the Dominican Republic, in a set by Rafael Scarfullery. This fine guitarist (named “best classical instrumental player” in his home country) played perhaps the most overtly romantic set of the festival, with lighthearted music like Miguel Pichardo’s jazzy “Dos Caprichos” and Román Peña’s “Otoño” and “Vals Criollo.”

The award-winning Bolivian guitarist Marcos Puña, playing a ten-string guitar, brought a lot of sly wit to a set that featured new works including “Leyenda” and “Por tu senda (Bailecito)” by Alfredo Dominguez – two pieces of rare beauty – as well as stylish works from the Brazilian composer-guitarist Paulo Bellinati and the Bolivian composer Matilde Casazola,

El Salvador’s Jorge Sanabria opened the final day of the festival with the music of Antonio Lauro and Agustin Barrios, as well as several Salvadoran composers. He gave a driving, impassioned account of the “Toccata Criolla” by Carlos Payes, and played Rafael Olmedo Artiga’s “Tres piezas intimas” with deep expressive detail, but a light, brainless waltz by the early 20th century composer David Granadino didn’t add much to the program.

The Peruvian guitarist Maria Luisa Harth-Bedoya has an open, expressive personality, and it shows in her playing. Most of her set came from her new CD “Ayres de Lima,” and was a delight. Opening with César Angeleri’s upbeat “Desde Lima,” she also played the fascinating “Sons de Carrilhoes”(by the Brazilian Joao de Pernambuco), and works from Ariel Ramírez and Héctor Ayala. But it may have been her interpretations of “Preludio No. 1” and “Choros No.1” by Heitor Villa-Lobos -- poetic and full of elegant mysteries -- that impressed the most.

Then came of the most daring and satisfying performances of the whole festival. Francisco Bibriesca is one of Mexico’s top guitarists, but instead of trying to impress the crowds with lightning virtuosity, he played an hour-long program of quiet, profoundly inward-looking pieces from his “Blue Road Tour” program. Playing with zen-like stillness, he explored works by Bellinati, Pujol and Marco Vinicio Camacho with deeply focused power and impact.

Two young female guitarists opened the festival’s last night of concerts. Colombia’s Irene Gomez – looking resplendent in a flowing red gown – put on a colorful performance featuring works by the Haitian composer Amos Coulanges (including an evocative piece called “Nan Fon Bwa,” which incorporated a wonderful snare drum effect), the poignant “Cacao” by Juan Carlos Guío, and two exceptional works by Jesús Emilio González. Gomez played them all with a delicate touch, showing herself to be a musician of subtle poetic power.

The most famous Paraguayan composers may be Agustin Barrios and Jose Asuncion Flores, and Paraguay’s Luz Maria Bobadilla focused on their work. But she played her own skillful arrangement of Barrios’ “Danza Paraguaya,” adding wildly colorful effects and well-chosen ornamentation, in a convincing and original account. A smile-inducing performance of Andras Bobadilla’s “Rancho Elsa,” and an updated version of Flores’s classic 1940 “India” (in the “guarania” style he created) added to Bobadilla’s fine set.

For the last two performances of the festival, though, the focus shifted to folk music – where the roots of much classical Latin music are found. The engaging young Brazilian composer Cacai Nunes has made a specialty of the 10-string guitar known as the "Viola Caipira," widely used as a folk instrument in Brazil, and played a number of his own works, which were steeped in folk rhythms and had a playful, almost improvisatory feeling.

And it was fascinating to hear the complex sonorities of his steel-stringed instrument -- though it did require frequent tuning. “We have a saying in Brazil,” Nunes joked, in Portuguese. “Half the time the guitarist is tuning, and the other half he’s playing out of tune.”

The festival ended as strongly as it began, with an entertaining and virtuosic performance by Juan Falu, perhaps Argentina’s most respected folk musician. A charismatic performer with an encyclopedic knowledge of his country’s music, Falu performed several traditional works with humor and down-to-earth directness. But it was his own music – sophisticated and compelling -- that made the deepest impression, and seemed to reflect both where Latin music has been, and where it was going – much like the festival itself.

Drowning in Love

(Asia Times, December 1996) Starting next week, the World Peace Foundation and Harvard University will host a three-day conference called "The Political and Economic Reconstruction of Burma." The speakers will include over two dozen well-respected scholars and public figures, who the sponsors promise will "contribute to an enlargement of the world's appreciation of the many dynamic forces that have shaped and are shaping Burma's response to its challenging political, social and economic environment."

And, significantly, not a single representative of the Myanmar government will be there.

"It's extraordinary," one of the invited speakers -- a well-known democracy activist -- told me over the phone. "Here is a group having what is supposed to be a serious discussion of Myanmar's future, and there won't be anyone presenting the views of the people who, in real terms, matter most: the military government."

Not that it really makes any difference. The ruling State Law and Order Restoration Council has as little use for Harvard as Harvard has for the Slorc. And in the time-honored tradition of academic conferences everywhere, the scholars will deliver their papers, politely disagree over details and then all go out for a drink. The actual impact of the conference on Myanmar's "political and economic reconstruction" is likely to be nil.

And that's unfortunate, because it underscores a key reality about the international debate over Myanmar: For all intents and purposes, it's just a game.

Rather than finding serious ways to open channels and bring about actual change in a highly authoritarian regime, the international movement to restore democracy to Myanmar has degenerated into an exercise in boycotts, name-calling and political correctness that is undermining the very goals it aims to achieve.

"It's become impossible to to talk realistically about the situation in Burma, because that means acknowledging that Aung San Suu Kyi's position is increasingly weak and that the Slorc is getting stronger," said the conference participant. "But if you come out and say that, you're shouted down and branded as a Slorc apologist. There's a tremendous sense of intimidation in the academic community."

And the impact has been telling. Ever since Aung San Suu Kyi was released from house arrest in July 1995, she's been canonized as a champion of democracy while pursuing a strategy of increasing irrelevance -- and one has led directly to the other.

The unquestioning admiration she's been bathed in has insulated her from reality and robbed her of hard-headed criticism and pragmatic advice, say many in Yangon.

Moreover, her sense of moral rightness is so strong and her hatred of the military government so intense that her strategic thinking is based on emotion, not analysis -- and has encouraged an equally intense and distorted response from the Slorc.

There are now simply two enemy camps, and the middle ground for dialogue has been squeezed out, to everyone's loss.

"Her real problem is that the world drowned her in love," a diplomat in Yangon told me last week. "The Nobel Peace Prize, the adulation of the press, and especially the uncritical support she got from Washington -- it all convinced her that she was an invincible moral force."

Unfortunately, this triumph of idealism over pragmatism has weakened Suu Kyi's position, while the Slorc is stronger in every way -- militarily, economically and diplomatically -- than it was in 1988. It has no need to talk with her, and from all appearances is increasingly hostile toward her. And now, with entry into ASEAN next year looking increasingly likely, the gap is likely to widen even further.

But has this served as a wake-up call?

I asked Suu Kyi recently whether, since the Slorc was probably going to hold onto power for a long time, it might make sense to work with the government in order to get economic help to the people of Myanmar. From the verbatim transcript:

"I don't see why we have to work with a system just because it's there," she said.

"Well, it's reality..." I answered.

"No, it is not," she said.

"It isn't?" I asked.

"Of course not," she answered.

"The government is not real?" I asked again, not sure I was hearing her correctly.

"Governments change all over the world, all the time," she answered. "I mean, this is unheard of, to stay with one system, I've never heard of such a thing. Systems change all the time. Besides, we are Buddhists, we believe in impermanence ... there is change all the time. What is here today, gone tomorrow. We are a Buddhist country, we cannot accept the eternal concept."  Experienced Myanmar-watchers are used to these kinds of platitudes from Suu Kyi, and they play well with Western college students, US Congressmen and institutes of world peace.

Experienced Myanmar-watchers are used to these kinds of platitudes from Suu Kyi, and they play well with Western college students, US Congressmen and institutes of world peace.

But on the ground in Yangon, she's viewed with a more skeptical eye. At a dinner party recently in the upscale Golden Valley neighborhood, not far from Suu Kyi's villa, a visiting merchant banker -- an American citizen, but Indian by birth -- mused on the careers of Suu Kyi and Indira Gandhi, both daughters of men who had led their countries.

"Indira surprised everyone," said the banker. "No one thought she would amount to much, so they tucked her away in an unimportant spot in the government and ignored her. But she turned out to be a much more clever and ruthless politician than they suspected, and she built up her power step by step, smashing her enemies as she rose. And eventually she climbed all the way up.

"But Suu Kyi," he continued, "is an amateur. She insists on starting at the top, so she's still stuck at the bottom. She's too full of moral virtue to be a successful politician. Which is why she'll probably never be in power in Myanmar."

Alan Rabinowitz: Saving the Tigers of South East Asia

By Stephen Brookes in Rangoon

By Stephen Brookes in Rangoon

for Asia Times

He’s travelled to some of the most remote and forbidding places on earth, from the highlands of Borneo to the jungles of Belize. But Alan Rabinowitz is no tourist -- as Director of the Science and Exploration Program at the Wildlife Conservation Society, he’s spent a lifetime making the world safer for the world’s most endangered creatures.

“Myanmar is to me, as a biologist, the most fascinating place in the world,” he says, restlessly shifting through piles of paper, cameras, maps and other gear in a hotel room in Yangon. Once called the “Indiana Jones” of wildlife science by The New York Times, Rabinowitz is a man on a mission. He’s about to head into the far north of the country to work on his latest project -- a tiger preserve that he hopes will become the largest contiguous protected forest in all of South East Asia.

“This country is a zoologist’s dream,” he says. Extending for more than a thousand miles from the foothills of the Himalayas to the lowlands of the Andaman Sea, Myanmar is made up of what he calls “transition zones” between major habitat types, where tigers and elephants reach the northern end of their range and red pandas and snow leopards meet the southern end of their range. “You get these in-between areas where pockets of evolution often occur,” he says. “It’s a fascinating area.” And the new Hukaung Valley tiger reserve is one of these unique areas.

The allure of the remote, largely pristine forests of Myanmar first drew Rabinowitz in 1993. “I was fascinated by what Myanmar could have left, because we knew that this was one of the most biologically diverse in South East Asia,” he says. “It gets the Indian fauna, the Chinese fauna, the Malay fauna -- incredible. But in the 1990s it had been locked away for many reasons, and we had no idea what was left. In countries like Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and China, despite all their grandiose claims, it was going to hell. There were very few tigers left, very few elephants, and environmental degradation was sweeping through Indochina.”

Rabinowitz started out advising Myanmar on ecological issues and training younger zoologists. But eventually he was deeply involved in the establishment of four national wildlife sanctuaries preserving more than 5000 square miles of habitat, and exploring the country.

“In 1997, we organized the first big expedition, going from Putao up to the last village, doing a biological survey,” he says. “We found incredible cultural diversity -- including the last mongoloid pygmies ever discovered,” a people known as the Taron. The trip also resulted in the extraordinary discovery of an entirely new species -- the leaf deer, the most primitive true deer in the world. (The story of these discoveries can be found in Rabinowitz’s 2001 book, “Beyond the Last Village.”

Courtesy of WCSBut Alan Rabinowitz’s new project may be his most exciting yet. The Hukuang Valley is one of the last remaining natural tiger habitats in Myanmar. “It’s a horrendous area, which is why wildlife thrives,” he says. “It’s horrible for malaria, its horrible for typhus, snakes, everything. That’s why tigers do great. The valley is 7,000 to 8,000 square miles, with about 5,000 to 6,000 square miles of beautiful, intact forest.

“Based on the survey we did, the government set up the Hukuang Valley Wildlife Sanctuary -- 2,500 square miles of incredible forest and diversity,” says Rabinowitz. “But then the government came to us and said, ‘If this area is so special, why not set up the whole valley as a tiger preserve?’”

He was overwhelmed, he says, by the proposal. “I wouldn’t even have dreamed of requesting 6,000 square miles as a protected area!” he says. “But they said, if you can show it’s justified, we’ll do it. Now, that’s incredible, because it will be the world’s largest tiger reserve.

“But we need to show that there’s a core population of breeding tigers in there, and this is no easy task,” he says. “It’s a dream and a nightmare together.”

While there are tigers, elephants, spotted leopards and many other endangered species, says Rabinowitz, there are also hunters, rattan collectors and gold miners -- and the interests of all have to be balanced. “If we can design a tiger reserve where there is a core, inviolate sanctuary,” he says, “but the other huge areas of forest can be multi-use areas -- for rattan collection, maybe even some local hunting if they need to -- and there will be staff in there controlling this, we can make this area work.”

And there’s a lot at stake. While Myanmar has fewer tigers than it should, he explains, it has much more forest than almost any country in Indochina. “If we can save the continuity of these forest areas, we can bring back a tiger population here which is going to far surpass India.”

Despite Myanmar’s extraordinary potential, though, Rabinowitz says conservation opportunities are being lost -- and for all the wrong reasons.

“WCS is a well known group,” he says, “but we’re a small player and our funds are limited. I’m killing myself trying to raise funds for the Burma program.” While the US Fish and Wildlife Service provided $40,000 for the first year of a three-year survey (the Myanmar government provided the rest), Rabinowitz says other conservation groups should get involved before its too late.

“We need outside funders to start coming in and engaging -- even if it's not money to us, I don’t care,” he says. “Other big conservation organizations who have far greater resources should be coming in here -- they’ve got big money, and they know this is important.

“The Smithsonian has been working here almost as long as we have, but they don’t have an office here, or local staff,” he adds. “They come and go. But big organizations like Conservation International refuse to come here, because unfortunately they seem to marry politics and conservation. They say they will not come here and do conservation under this government, which is the most absurd, horrible thing there can be -- because conservation has nothing to do with politics, and even [opposition leader] Aung San Suu Kyi has said it. She says, when the political situation changes, we need healthy people in the country, and we need forests and wildlife left.”

Moreover, says Rabinowitz, Myanmar is a country that seems genuinely committed to conservation.

“I’m not naive -- I’ve worked 20 years in this field, in many, many countries. And there are countries I’ve walked out of, like China and Malaysia, where they just talk a good game and don’t follow anything up. And this government, so far, has followed through. Outsiders can say what they want, but I can show them the facts. Come, and I’ll show you where local people are now better off in the protected areas. They have salt, medicine, and other things where the government has staffed every protected area they’ve set up.

“The outside world needs to realize that change occurs best from economic engagement,” he says. “The human rights activists don’t want to hear this, but that’s the reality. You want to help these countries in terms of saving their resources and helping the local people, it comes from on-the-ground engagement.”

Advertisers Target New, Improved Myanmar

By Stephen Brookes • Asia Times • March 23, 1996

________________________________________________________________________________

They come at you relentlessly, one beautiful, smiling Myanmar woman after another. No sooner has one held up her package of pickled tea leaves than another appears on the screen, hawking makeup or a new music cassette or a local brand of "blood purifier." On and on they come, with shampoos and sunflower seeds and local soft drinks -- a solid twenty minutes of commercials every night on the country's one television channel.

They come at you relentlessly, one beautiful, smiling Myanmar woman after another. No sooner has one held up her package of pickled tea leaves than another appears on the screen, hawking makeup or a new music cassette or a local brand of "blood purifier." On and on they come, with shampoos and sunflower seeds and local soft drinks -- a solid twenty minutes of commercials every night on the country's one television channel.

Welcome to Myanmar's newest craze -- consumerism.

In the past year, advertising has radically changed the once-sleepy face of Yangon. It's not just television that has become clogged with commercials: The main traffic circles are ringed with new, high-quality billboards, the avenues are lined with banners advertising Canon and Daewoo, and the streets are jammed with painted buses touting Red Cow milk and Chungwha Shanghai cigarettes. And the modern, English-language street signs that sprouted across the city a few months ago also double as advertisements for Tiger Beer.

"We're just at the beginning of advertising here," said Michael Lim, director of Myanmar Spa Today Advertising Ltd. "Myanmar is developing into a consumer society. Things are better now than ever. People have more money, and they like to spend it."

Lim's agency, a joint venture with Thailand's Spa, is the latest of several international advertising companies to take advantage of -- and encourage -- Myanmar's consumerist boom. Both the British-owned Bates Advertising and the Singapore joint venture Myanmar Media International Ltd. have had offices in Yangon for two years, and McCann Marketing set up shop in January.

"Myanmar has incredible potential," said Thomas Crawford, Bates' international account director, citing the rapid growth of the economy, the pent-up desire for consumer goods and the influx of foreign companies. "This market is going to be phenomenal."

Bates, the largest buyer of television and cinema advertising in Myanmar, represents a dozen high-profile clients including Lucky Strike, Heineken and J&B Whiskey. And while the market is still small for some of those products, Bates executives say, it's worthwhile getting in early.

"The market here for upscale products is only about 500,000 people -- 800,000, tops," said Peter Thein, a consultant with Bates. "But 110 percent of our clients are optimistic. Eighty to ninety percent of them," he added, "say they would be willing to lose money while building a presence here -- but none of them are losing money."

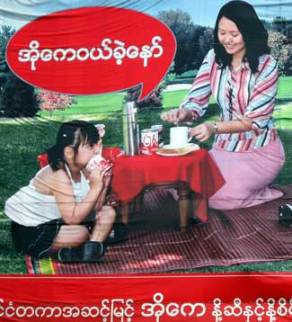

OK Coffee mix in YangonAdvertisers say the prime market is business people between 25 and 40, and women -- who generally spend more money than men, and are often the breadwinners in Myanmar -- are clearly the target of most the advertising.

Younger people are being watched, as well. "Fifty-four percent of the population is under the age of 25," said Bates' Thein. "If we didn't target them, we'd be stupid."

And while Chivas Regal is advertised in Air Mandalay's in-flight magazine, Myanmar's per capita income still only around US$300 a year, and the primary market is for low-cost items.

"It's a classic pattern," said one executive. "You start with cigarettes, alcohol, toiletries. The property business comes next, and we're starting to see that now. Look at Toyota -- they import only their lower end models, none of the luxury cars."

But tastes are changing, and foreign brands are increasingly in demand as status symbols. Importers of luxury goods privately confirm that some upscale products are priced below cost in order to build a market, and consumers are getting more sophisticated.

"Spending power is higher, and people want new products," said Lim. "In three to five years, they will be buying premium products."

While lauding the market's potential, though, advertising professionals also warn that Myanmar presents unique obstacles. The country endured three decades of a socialist, isolationist regime that left its economy in tatters, and is only now moving toward an open market. Its markets are undeveloped, little is known about what consumers want, and reaching the public is difficult, since the media are largely state-owned -- when they exist at all.

"There are no outlets here!" complained one ad executive in exasperation. "There are only five air-conditioned movie theaters in the entire country. There are few, if any, quality magazines or newspapers, and only one television station. So you have to be creative."

Myanmar's brutal tropical weather -- with a blistering hot season and a drenching monsoon -- also hinders advertising, wreaking havoc on billboards and outdoor displays. Electricity, while improving, is still notoriously unreliable. And while modern, back-lit billboards have started to appear, many advertisers still shun them.

And there are government restrictions on what advertisers can run: no nudity, and nothing offensive to the national religion or culture. Every form of advertising -- even calendars -- has to pass a censorship board.

With few entertainment outlets, Myanmar's sole television channel has, to some degree, a captive audience, and some advertisers think that makes it effective. "The audience here is fresh, very receptive," says Michael Lim. "We don't know exactly how many people watch, but about 70 to 80 percent of households in the cities have televisions."

Advertising the old-fashined wayNot everyone agrees. "Television is seen all over the world as the best medium, but it's different here," says MMI's Germaine Ng. "There are brownouts, the ownership of televisions is low, and the people who can afford tvs also get satellite dishes."

Moreover, the goverment-set rates for tv advertising give a huge advantage to local companies. A 30-second spot during weeknight prime time will cost a foreign advertiser US$780, but a Myanmar advertiser pays only a fraction of that, encouraging a rash of amateurish, low-budget commercials. And the ads aren't spaced out through an evening's programming; they're run in two separate twenty-minute bursts known in the trade as "walls."

"Frankly, it's a bit of a nuisance," grumbles one advertising executive in Yangon. "It's so cheap to advertise that everybody with a new product tests it out on television. And who wants to watch twenty or thirty commercials in a row?"

The obstacles to traditional "above the line" advertising like tv and billboards have prompted many advertisers to go "below the line," sponsoring rock concerts, sports events, lucky drawings and other promotions. One cigarette maker put cash in some of its packs. Cosmetic-maker Pantene recently sponsored a beauty contest. And all the major ad agencies set up booths during Myanmar's raucous Water Festival in April -- the bigger and more attention-getting, the better.

"We built a humongous stand for Benson and Hedges last year," said Crawford. "Ninety-two feet long, with smoke machines, a rock band -- it was wild."

But ad agencies may face their most crucial challenge in convincing the local business community that it needs them

"They're still at a primitive stage in the way they think about advertising," said Spa's Lim. "They think their products are well-known, so they don't need to advertise."

Germaine Ng of MMI agrees. "The idea of marketing doesn't really exist here; local companies just produce and distribute their products. So we work out a marketing approach for them. But it can take a long time to get them to accept the need for it."