Smoke Without Fire in the Drug War?

By Stephen Brookes in Rangoon

for Asia Times

Rising out of the dust like a pink and gold hallucination, Myanmar's new Museum of Narcotic Drugs loomed above the crowd of soldiers, politicians, ambassadors and journalists as Gen. Khin Nyunt - one of the top leaders of the ruling military junta - took the podium.

"It is a well known fact," he said, "that in Myanmar, the government and the whole populace residing in the border areas have whole-heartedly committed themselves to eradicate the narcotics drugs problem. However, some Western countries who turn a blind eye to our successful efforts in this regard are still unfairly accusing Myanmar by disseminating untrue reports and exaggerated news."

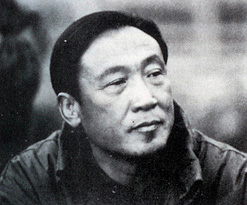

Gen. Khin Nyunt opening the Museum of Narcotic Drugs Stephen Brookes The museum opening in northeastern Shan state was part of a broad counterattack by the junta against charges that it was not cooperating in the fight against drugs - and, according to some United States officials, is even involved in the trade itself, from trafficking to money-laundering.

"Burmese authorities have made no discernible efforts to improve their performance," senior US narcotics official Robert Gelbard stated last November. "From a hardheaded, drug-control point of view, I have to conclude that SLORC has been part of the problem, not the solution."

In May, US Secretary of State Madelaine Albright took up the fight, saying drug money had penetrated all reaches of society and traffickers were becoming "leading lights" in Myanmar. "Drug money is so pervasive in the Burmese economy that it taints legitimate investment," she warned.

says one expert, "but where's the smoking gun?"

And in April, journalists Leslie Kean and Dennis Bernstein wrote in the Boston Globe: "Burma is swiftly becoming a full-fledged narco-dictatorship, with all aspects of the government either heavily influenced by or directly incorporated into the burgeoning drug trade."

But some drug experts, both inside and outside of Myanmar, say the matter is not so simple -- and that the country is merely a scapegoat for the West's failed war on drugs.

"The State Department says that opium production has doubled since the junta came to power in 1988, therefore the junta is responsible," one Western official in Yangon said.

"But that's a phony argument. The key factor in 1988 was that the US decertified Burma and stopped its drug assistance. The US was providing about 80 percent of the funding for fighting drugs, so naturally when that money dried up, opium production increased. But rather than admit their error, the US is blaming the junta."

Other drug enforcement officials agree. "The Burmese were extremely cooperative with US law enforcement during the time I was there," said Barry Broman, who spent two years at the US embassy before retiring last year. "They provided major assistance. The problem was the limited amount of assistance we could give the Burmese."

Broman, who spent several decades investigating the narcotics trade in Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam before being posted to Myanmar in 1994, is one of America's most knowledgeable experts on the complex world of Asian drug trafficking.

"There are a lot of accusations that the military is involved in narcotics, but no one's produced any evidence - so where's the smoking gun?" he said, during a recent trip to Yangon.

"In my experience, the trade is not institutional in Burma. That's not to say that people aren't profiting - there's indirect profiting from the narcotics trade. But across the border, you find Thai politicians and generals in bed with the traffickers. That's not the case here."

Khun Sa But critics like Albright point to the new role that former drug lords like Lo Hsing Han and Khun Sa are allegedly playing in the Myanmar economy. Myanmar's refusal to extradite Khun Sa to the US, they said, is proof of its complicity in the drug trade.

Broman takes a different view. "On their own, the Burmese effected the capture of Khun Sa," he said. "They made a major dent in the drug trade, and we gave them no credit.

"The human rights people say they cut a sweetheart deal, but I don't believe that. In the US, we call it a plea bargain. And in this case, justice was served, because Khun Sa is out of the drug business. And that means 12,000 armed men [soldiers in Khun Sa's army] are no longer in the drug business."

Moreover, said Broman, it's unlikely that Khun Sa is as rich as many people assume. "It's a mistake to think of him as a megabucks guy, like the Columbian cocaine lords," he said.

"With cocaine, you have cartels that control everything from the coca fields to the dealers in New York, so the profits are huge," he explained.

"But unlike cocaine, heroin changes hands many times before it gets to the buyer. Khun Sa would buy the opium from producers, then process it and sell it to a politician or a general in Thailand, who would sell it to someone else in Hong Kong or Vancouver. The big profit is all outside Asia."

Myanmar government officials also discount the idea of drug lords as the new economic kingpins. When asked how much money Khun Sa was pumping into the economy, one officer from the Defense Ministry just laughed.

"They cost us money!" he said. "We have to support all those former Mong Tai army soldiers. After Khun Sa surrendered, they were on their own - we gave them money and resettled them. We don't want to fight them anymore, so we have to find something else for them to do."

What Western critics fail to understand, a number of diplomats and drug officials say in Yangon, is that the opium-producing areas are controlled not by the junta, but by armed ethnic insurgent groups along the border, including the Wa, the Kokan and the Shan.

The military is primarily interested in exerting political control over these areas, so has had to come to political settlements with the insurgent groups who have traditionally funded themselves with drug profits.

"These guys were shooting Burmese for a living," said Broman. "The drug profits buy bullets that kill Burmese soldiers. So it's in the Burmese interest to control drugs."

But to get rid of the existing opium economy and replace it with something new, time is needed. "The US wants an instant solution to the problem, but that's not realistic," said one drug expert in Yangon.

Is Myanmar's anti-narcotic campaign real, or just an exercise in public relations? Broman and others have said it's real, and is now getting encouragement from an unexpected source.

"The Chinese are putting pressure on Burma," he said. "China has a growing addiction problem, and they've told the Burmese they want them to get a handle on it. China and the US both have the same message," he added, "but the Chinese are doing a lot more in terms of helping."

References (6)

-

Response: Agnes Lights

Response: Agnes Lights -

Response: Xiaomi Mi6 Specifications

Response: Xiaomi Mi6 Specifications -

Response: clanlab.co.nzAll are using this site daily for great and informative tips here after reading this somke without fire in the drug war. Really very impressive and useful for all,keep doing in the same way with testing.

Response: clanlab.co.nzAll are using this site daily for great and informative tips here after reading this somke without fire in the drug war. Really very impressive and useful for all,keep doing in the same way with testing. -

Response: How to Quit Smoking 10 Steps

Response: How to Quit Smoking 10 Steps -

Response: san diego rehab

Response: san diego rehab -

Response: Things to do post

Response: Things to do post

Reader Comments (1)

http://www.worldendingin2012.org