Reading Between the Lines

By Stephen Brookes in Yangon

For Asia Times

I was sitting in a Yangon restaurant waiting for a friend the other day, and was deeply immersed in the New Light of Myanmar -- the official newspaper here -- when he arrived. "Sorry I'm late," he said, then noticed the paper. "Do you actually read that thing?" he asked, with an exaggerated grimace of distaste.

"I have to, it's part of my job," I said, folding the paper quickly into my briefcase. But the truth is that, though the state-run paper is written like a Soviet tank manual and has all the flair and vitality of a grocery list, I read it every day -- and find it fascinating.

"I have to, it's part of my job," I said, folding the paper quickly into my briefcase. But the truth is that, though the state-run paper is written like a Soviet tank manual and has all the flair and vitality of a grocery list, I read it every day -- and find it fascinating.

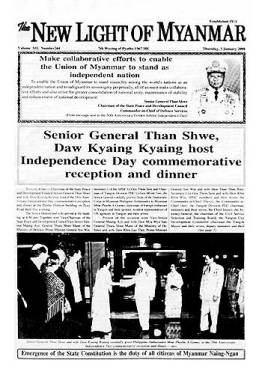

For the New Light of Myanmar is the English-language voice of the military State Peace and Development Council. It's the main vehicle the SPDC uses to explain itself to the outside world, and it's much like the junta itself -- stolid, no-nonsense and deeply reluctant to divulge information. If you're looking for lively, in-depth news and analysis, the New Light is not the place to look. Most real information flows on the rumor mill in Myanmar, not in the papers. But for insight into how the SPDC sees itself, there's no better source.

Of course, it's sometimes a tough slog -- this is a government, remember, that even has a censorship board for calendars. They don't have to worry about boosting circulation, or getting more advertisers, or beating the competition. There is no competition. So there aren't any features, "lifestyle" stories, feisty op-ed pages or comics. They don't even have Doonesbury.

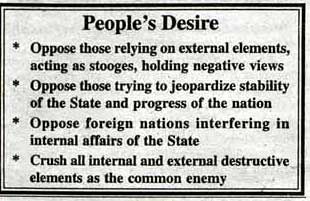

In fact, even its staffers admit that the paper is a tad formulaic. Each day starts with a stern recitation of the SPDC's sixteen political, economic and social objectives and then takes off from there. There are firm exhortations to the citizenry to drive safely, not to smoke, and to uphold the emergence of a constitution. If a new ambassador has been appointed from somewhere, there will be a solemn announcement. If a top official makes a speech, the speech will be reprinted down to the last syllable. If a government minister tours a new beanfield, there will be a new beanfield story.

Yet, the paper can be oddly charming in spite of itself. On slow news days, page two will sport an old-fashioned photo of a young woman posing in front of a pagoda with a clunky caption like, "Two samples of Myanmar beauty." (This is in the "Come, Visit Myanmar" section.) The government is always running competitions and festivals of one kind or another; last week the results of the Mayor's Cup Fruit and Flower Show were announced, including the winners of the "foreign orchids event", the "garden croton event" and, of course, the "fern event".

But hard news in Myanmar is tougher to find. The notions of "useful information" and "story line" are not well-developed, and most articles are simply a statement that a certain event occurred, with a long list of the people who attended. A typical front-page story will note that a top SPDC official visited a construction site, name every member of his entourage, then reveal that the official "issued necessary instructions to the authorities concerned". End of story.

But even such lists can provide useful glimpses into life in Yangon. Take the January 4 article on the opening of a new furniture showroom. Pretty boring, right? And the story just noted that a company called Sinma Furnishings opened the shop with its business partner. Simple enough -- except that the partner is the Welfare Society of the Bureau of Special Investigation, and the attendees included the Minister for Home Affairs, the Director of Public Relations and Psychological Warfare, and the head of the Myanmar Police Force.

But even such lists can provide useful glimpses into life in Yangon. Take the January 4 article on the opening of a new furniture showroom. Pretty boring, right? And the story just noted that a company called Sinma Furnishings opened the shop with its business partner. Simple enough -- except that the partner is the Welfare Society of the Bureau of Special Investigation, and the attendees included the Minister for Home Affairs, the Director of Public Relations and Psychological Warfare, and the head of the Myanmar Police Force.

Fascinating business, furniture.

In fact, stories on international investment -- actual or potential -- tend to dominate the news. Like it or not, trade delegations and visiting heads of corporations usually get their pictures in the paper when they meet with government officials, with a short article noting who was present and a vague statement that "topics of mutual interest" were discussed. And in Visit Myanmar Year, the arrival of a shipload of tourists will usually merit a photo and short article noting the number of visitors, their nationality and, for some reason, the exact time the boat actually docked.

But often what's most interesting is the news that doesn't make it -- in other words, the political news. The events that propel Myanmar onto the front page of the international press are usually ignored in the New Light of Myanmar, and the release of opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi from house arrest in 1995, the detention of hundreds of NLD members this past May, the student protests in December, the placement of tanks around the city -- all passed without a peep.

Of course, the paper does discuss many of these events -- but in the opinion section, not the news. There seem to be a tacit admission that everyone has heard the latest new on the grapevine, and the newpaper's job is to put the right spin on it. Suu Kyi's activities are never reported straight, for example, but rather discussed in long, pseudonymous and sometimes quite vicious essays on the dangers of "evil destructionists" and "dastardly neo-colonialism."

Analysts say that's partly because the SPDC is a large group, and needs time to discuss what response it will take to important events (which also explains the formulaic approach to reporting). But the exception to the "if-it's-on-CNN-it's-not-in-the-New Light of Myanmar" rule was a bombing late on the night of December 25, in which five people were killed.

To the interest of many in Yangon, the news was reported in the paper the very next morning -- an unusually rapid response that prompted the usual tea-leaf-reading in this rumor-prone city.

"Usually they keep any news on ice for a while, until everyone has agreed on how to play it," said one diplomat in Yangon. "It's fascinating that they reported this so quickly -- clearly there was no need to forge a consensus. But what exactly does that mean?"

Water on the Brain, and Everywhere Else

By Stephen Brookes in Yangon • for Asia Times

________________________________________________________________________________________

On Friday, four days of hell will break loose in Yangon. Either that, or four days of wet, raunchy, non-stop animal fun. How you see it depends on how old you are -- and how much pent-up hormonal aggression is pulsing through your veins.

Photos by Min Zaw Mra Because on Friday, the annual water festival known as Thingyan begins -- a prelude to the start of the Myanmar new year on April 16. For most people, it's the most important festival of the year, a traditional celebration for washing away the sins and bad luck of the previous year.

And many people celebrate it with great dignity. In the countryside, villagers will approach you with a smile and gently pour a ladle of cool, perfumed water over your head -- a kind of peaceful benediction.

But in the cities, you better run for your life -- or someone with a seriously bad attitude will try to annihilate you.

Sensible people either leave town, or gather up their daughters and bolt the doors. Because Thingyan serves as a pressure valve for this highly-controlled, ultra-repressed society, and is the one time in the year when people can abandon their inhibitions, let loose a primal howl and get in touch with their anger, as the headshrinkers say.

The catalyst for the resulting mayhem is water -- oceans of it. Huge stages called pandals are set up all over the city, manned by hose-bearing women who spray passers-by with jets of ice-cold water. To the throbbing beat of heavy metal bands, people roam around in the backs of pick-up trucks nourishing themselves on Mandalay Beer, screaming like animals and getting as wet as they possibly can -- until they're reduced to sodden, incoherent lumps and have to be wheelbarrowed home.

Sounds like fun, right? Listen to the advice of Saw Myat Yin, author of the very useful and sober-minded book, "Culture Shock: Burma."

"One should not only be careful of getting hurt from very rough water throwing, but should be wary of pickpockets in the crowd," she writes. "Ears should be kept well covered with thick towels to avoid injury. Eardrums have been known to be pierced by water prayed at high pressure ... traffic accidents are common ... water throwers try to get rid of their grievances and aggression at this time."

Last year, rumor has it, six people had their eyes put out from water balloons.

To some observers in Yangon, the wildness of Thingyan is only natural. The military government allows few opportunities for self-expression, and none for rebellion or dissent. Any dispute with the authorities ends with: "Because we're the government, that's why -- now go to your room." And with Myanmar's young people chomping at the bit, the government has been issuing stern instructions on the correct way to enjoy themselves, i.e. "to celebrate the festival in accord with Myanmar traditions and to enable the people to have fun in proper manner during the festival, to be refreshed after the festival for discharging duties with full vigor in the new year and to preserve Myanmar traditions."

You get the idea.

Last week, Brig-Gen Khin Maung Than -- whose title is "Commander of the Yangon Command" -- addressed a meeting of the Water Festival Discipline Committee (yes, there is such a thing), where he declared that "punishment will be meted out to those who use unclean water, ice packs and water balloons injurious to others," and warned against drunkenness, "counterculture modes of dress," and "attempts to exploit the festival for political gain and incitement."

He also noted that 42 special courts will be set up in townships to pass sentences should criminal cases occur during the festival. (In case you're wondering: the penalty for throwing a water balloon is three years in the slammer.)

Now, "exploiting the festival for political gain" -- living in Yangon, you get used to that kind of language. The government is forever warning in the official media about the need to fight enemies of the state, and to beware of "neo-colonialists" who would foment social dissolution. It's clearly a warning to supporters of dissident Aung San Suu Kyi not to get any ideas about turning Thingyan into a political event.

But what's interesting about the water festival is the apparent collusion between the people who are acting out their aggressions by violently throwing water, and their willing victims. They coexist in a brutal psychological balance which seems to be satisfying and cathartic for both sides.

"Thingyan is when Yangon's masochists and sadists get out in the streets and feed on each other," explained one diplomat. "We've decided to go to Cambodia until it's over."

Thingyan in Yangon That dominant/submissive relationship could point to some interesting insights into the politics of control in a military state. But it may actually have more to do with sex.

"Thingyan is a very erotic time for young people," a Myanmar friend in her forties explained. "They don't have many opportunities to meet, and really, they hardly know what each other looks like. Underneath, I mean. But everybody's soaked during the festival, so they can all have a good look." She paused thoughtfully for a moment, and added, "There are always a lot of sudden elopements right afterwards."

And there's also the interesting way that the fluids are exchanged, so to speak. During Thingyan, both boys and girls throw water on each other. But generally it's the girls who take the aggressive role: The boys are driven around passively in the backs of pickup trucks shouting obscene comments at women in the street, while the girls turn the hoses on them and spray.

Hmm.

But the most intriguing new development in Thingyan, say some longtime residents, is its growing commercialism. While many of the pandals are still sponsored by government agencies and community organizations, many more belong to companies -- and the biggest are raucous, three-dimensional, live-action advertisements for cigarettes and beer.

And these pull out the stops, hiring rock bands, smoke machines, famous actresses to handle the hoses -- the whole bit. Their pandals are true extravaganzas. So much so, apparently, that some of the government ministries are getting a bit jealous -- and fighting back in the best way they know.

"One of the ministries just informed us we can't use the rock band we had hired -- they want it for themselves," one advertising executive in Yangon told me, rolling his eyes. "So we're being allowed to hire another rock band, but get this -- they're telling us that the band has to play traditional classical music!"

In the Strange Church of the Dictatorship

By Stephen Brookes in Rangoon

for Asia Times

Suggest a trip to the Defense Services Museum, and most visitors to Yangon balk. They gather their children behind them and back away warily, muttering about pagodas and tight schedules. But for anyone really interested in understanding Myanmar, the museum is an essential stop. It's a direct and fascinating look into the conflicted heart of the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) -- the military junta that runs the country.

Since the SLORC assumed power after the uprisings of 1988, it's been trying to present a kinder, friendlier face to the world -- and pounding that message in as often as possible. There are billboards all over the country singing the praises of the Tatmadaw (as the military is known), insisting that it will never betray the country. And the defense museum, which is the junta's forum for explaining itself to the people, is full of the strange tension between rigid control and apparent goodwill that underlies almost everything that the SLORC does.

Since the SLORC assumed power after the uprisings of 1988, it's been trying to present a kinder, friendlier face to the world -- and pounding that message in as often as possible. There are billboards all over the country singing the praises of the Tatmadaw (as the military is known), insisting that it will never betray the country. And the defense museum, which is the junta's forum for explaining itself to the people, is full of the strange tension between rigid control and apparent goodwill that underlies almost everything that the SLORC does.

That tension is clear from the moment you walk in the gates: two unsmiling, machinegun-toting guards examine you, peer into your bag for cameras, then allow you to approach a small ticket booth. Over the ticket taker's window, there's a small sign announcing the $3.00 entry fee -- and it's drawn in red pencil with a big, red heart.

Despite that oddly charming note, it's clear at first glance that the museum is meant to be epic in scale and authoritative in tone -- a monument to the power of the Tatmadaw. The building is an exercise in epic International Style, with Mussolini-esque sweeps of open space and armed guards stationed picturesquely by the doors.

But once through the marble-columned portico and past a stern photographic gauntlet of the country's military leaders, you immediately notice that you're alone. Aside from the occasional bewildered tourist and the ubiquitous cleaning ladies -- who look up, startled, as you pass -- the museum is almost always empty.

There are, of course, weapons -- thousands of them. And there's an infectious enthusiasm about the weaponry on display, from Japanese artillery seized in WWII, to vast arrays of machine guns and depth charges, to a selection of armored cars, to the deck and cabin of a Myanmar patrol boat, removed whole and mounted on the floor. Another huge, hanger-like room holds fifteen warplanes and helicopters, complete with exhibits on parachutes and ejection seats.

And the wonderful thing about the displays is that they aren't done in the sober, reflective way that you find at, for example, the Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC. Here, the guns are flanked by lurid dioramas that look as if they were designed by 12-year-old boys. One shows a gory plane crash, replete with broken bodies, screaming victims and melted plastic planes. Another has a mismatched set of tanks rolling through a landscape of demolished houses -- with a perfect pagoda gleaming on a perfect hill in the background. And a huge aquarium, filled with greenish water and small plastic boats, depicts an outsized frogman attaching a mine to the underwater struts of a bridge. On the front of the aquarium is a sticker that reads, "I Love Tetra."

But the weaponry exhibits run out quickly, and the broader, more complex range of the military begins to reveal itself. Mount the stairs to the second floor and what looks like a souvenir shop turns out to be a display of shoes from the Tatmadaw Footwear Factory. There are combat and jungle boots, of course -- but also rows and rows of furry slippers and three different styles of golf shoe. And a whole separate case holds what are labeled "experimental products," including gold high heels and a green suede "shooting vest."

As you move from room to room and from floor to floor, the width of the SLORC's grasp over almost everything in the country becomes clear. One large room is given over to agriculture, complete with dioramas of cows in fields, a stack of baskets for holding pigs and a case full of cans of Tatmadaw "Bamboo Shoot and True Pea." Another room houses detailed displays of the military's medical advances, and yet another contains records of the SLORC's accomplishments in foreign policy.

Nor is the economy neglected. The next floor up houses an exhibit of credit cards (something not seen until a year ago) and bank passbooks for foreign currency holders -- another novelty. There are displays of the country's exports (including jars of fish in formaldehyde) and an exhibit showing "export garments of joint ventures" that highlights shirts bearing the Eddie Bauer logo -- even though that company pulled out of Myanmar last year because of criticism over the SLORC's human rights policies.

In fact, the government seems to be curiously nonchalant about such outside criticism. Charges that it conscripts labor and mistreats political prisoners don't seem to worry it. The top floor of the museum is proudly home to an informative exhibit on the prison system itself, explaining the SLORC's philosophy ("to utilize fully unused prisoners' services in national development projects") and detailing the Prison Department's operations. And the whole display is right next to another one explaining the workings of the Manpower Department, with a huge national map showing "prisons, breeding work sites, agricultural sites and quarry sites."

But it's not until you climb the last flight of stairs and make it to the top floor that the meaning of the whole museum finally becomes clear. For here (after you've found an attendant and gotten him to turn the lights on for you) is the government's vision of its own future.

And it has nothing to do with firepower. Laid out in loving detail under a wide glass case is a vast, detailed model of the Future of Yangon. There are the old colonial buildings, the wide streets, the green parks, carefully painted and built to scale. But they only seem to be a backdrop for the modern new buildings going up -- the Traders Hotel, the FMI Building, the International Business Center and dozens of others. And as they go up, the neglected city of Yangon is being transformed.

And that could be what the SLORC sees as its next great goal. For it is now arguing that, with the country stable and at peace, its new job is to develop the economy and bring Myanmar up to par with the rest of South East Asia. Forget the guns and the bloody dioramas of the first floor -- the military's new battlefield is the economy.

Drowning in Love

By Stephen Brookes in Yangon

For Asia Times, December 1996

Starting next week, the World Peace Foundation and Harvard University will host a three-day conference called "The Political and Economic Reconstruction of Burma." The speakers will include over two dozen well-respected scholars and public figures, who the sponsors promise will "contribute to an enlargement of the world's appreciation of the many dynamic forces that have shaped and are shaping Burma's response to its challenging political, social and economic environment."

And, significantly, not a single representative of the Myanmar government will be there. "It's extraordinary," one of the invited speakers -- a well-known democracy activist -- told me over the phone. "Here is a group having what is supposed to be a serious discussion of Myanmar's future, and there won't be anyone presenting the views of the people who, in real terms, matter most: the military government."

"It's extraordinary," one of the invited speakers -- a well-known democracy activist -- told me over the phone. "Here is a group having what is supposed to be a serious discussion of Myanmar's future, and there won't be anyone presenting the views of the people who, in real terms, matter most: the military government."

Not that it really makes any difference. The ruling State Law and Order Restoration Council has as little use for Harvard as Harvard has for the Slorc. And in the time-honored tradition of academic conferences everywhere, the scholars will deliver their papers, politely disagree over details and then all go out for a drink. The actual impact of the conference on Myanmar's "political and economic reconstruction" is likely to be nil.

And that's unfortunate, because it underscores a key reality about the international debate over Myanmar: For all intents and purposes, it's just a game.

Rather than finding serious ways to open channels and bring about actual change in a highly authoritarian regime, the international movement to restore democracy to Myanmar has degenerated into an exercise in boycotts, name-calling and political correctness that is undermining the very goals it aims to achieve.

"It's become impossible to to talk realistically about the situation in Burma, because that means acknowledging that Aung San Suu Kyi's position is increasingly weak and that the Slorc is getting stronger," said the conference participant. "But if you come out and say that, you're shouted down and branded as a Slorc apologist. There's a tremendous sense of intimidation in the academic community."

And the impact has been telling. Ever since Aung San Suu Kyi was released from house arrest in July 1995, she's been canonized as a champion of democracy while pursuing a strategy of increasing irrelevance -- and one has led directly to the other.

The unquestioning admiration she's been bathed in has insulated her from reality and robbed her of hard-headed criticism and pragmatic advice, say many in Yangon.

Moreover, her sense of moral rightness is so strong and her hatred of the military government so intense that her strategic thinking is based on emotion, not analysis -- and has encouraged an equally intense and distorted response from the Slorc.

There are now simply two enemy camps, and the middle ground for dialogue has been squeezed out, to everyone's loss.

"Her real problem is that the world drowned her in love," a diplomat in Yangon told me last week. "The Nobel Peace Prize, the adulation of the press, and especially the uncritical support she got from Washington -- it all convinced her that she was an invincible moral force."

Unfortunately, this triumph of idealism over pragmatism has weakened Suu Kyi's position, while the Slorc is stronger in every way -- militarily, economically and diplomatically -- than it was in 1988. It has no need to talk with her, and from all appearances is increasingly hostile toward her. And now, with entry into ASEAN next year looking increasingly likely, the gap is likely to widen even further.

But has this served as a wake-up call?

I asked Suu Kyi recently whether, since the Slorc was probably going to hold onto power for a long time, it might make sense to work with the government in order to get economic help to the people of Myanmar. From the verbatim transcript:

"I don't see why we have to work with a system just because it's there," she said.

"Well, it's reality ..." I answered.

"No, it is not," she said.

"It isn't?" I asked.

"Of course not," she answered.

"The government is not real?" I asked again, not sure I was hearing her correctly.

"Governments change all over the world, all the time," she answered. "I mean, this is unheard of, to stay with one system, I've never heard of such a thing. Systems change all the time. Besides, we are Buddhists, we believe in impermanence ... there is change all the time. What is here today, gone tomorrow. We are a Buddhist country, we cannot accept the eternal concept."

Stephen Brookes with Aung San Suu KyiExperienced Myanmar-watchers are used to these kinds of platitudes from Suu Kyi, and they play well with Western college students, US Congressmen and institutes of world peace.

But on the ground in Yangon, she's viewed with a more skeptical eye. At a dinner party recently in the upscale Golden Valley neighborhood, not far from Suu Kyi's villa, a visiting merchant banker -- an American citizen, but Indian by birth -- mused on the careers of Suu Kyi and Indira Gandhi, both daughters of men who had led their countries.

"Indira surprised everyone," said the banker. "No one thought she would amount to much, so they tucked her away in an unimportant spot in the government and ignored her. But she turned out to be a much more clever and ruthless politician than they suspected, and she built up her power step by step, smashing her enemies as she rose. And eventually she climbed all the way up.

"But Suu Kyi," he continued, "is an amateur. She insists on starting at the top, so she's still stuck at the bottom. She's too full of moral virtue to be a successful politician. Which is why she'll probably never be in power in Myanmar."

Smoke Without Fire in the Drug War?

By Stephen Brookes in Rangoon

for Asia Times

Rising out of the dust like a pink and gold hallucination, Myanmar's new Museum of Narcotic Drugs loomed above the crowd of soldiers, politicians, ambassadors and journalists as Gen. Khin Nyunt - one of the top leaders of the ruling military junta - took the podium.

"It is a well known fact," he said, "that in Myanmar, the government and the whole populace residing in the border areas have whole-heartedly committed themselves to eradicate the narcotics drugs problem. However, some Western countries who turn a blind eye to our successful efforts in this regard are still unfairly accusing Myanmar by disseminating untrue reports and exaggerated news."

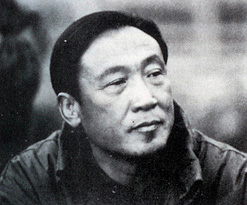

Gen. Khin Nyunt opening the Museum of Narcotic Drugs Stephen Brookes The museum opening in northeastern Shan state was part of a broad counterattack by the junta against charges that it was not cooperating in the fight against drugs - and, according to some United States officials, is even involved in the trade itself, from trafficking to money-laundering.

"Burmese authorities have made no discernible efforts to improve their performance," senior US narcotics official Robert Gelbard stated last November. "From a hardheaded, drug-control point of view, I have to conclude that SLORC has been part of the problem, not the solution."

In May, US Secretary of State Madelaine Albright took up the fight, saying drug money had penetrated all reaches of society and traffickers were becoming "leading lights" in Myanmar. "Drug money is so pervasive in the Burmese economy that it taints legitimate investment," she warned.

says one expert, "but where's the smoking gun?"

And in April, journalists Leslie Kean and Dennis Bernstein wrote in the Boston Globe: "Burma is swiftly becoming a full-fledged narco-dictatorship, with all aspects of the government either heavily influenced by or directly incorporated into the burgeoning drug trade."

But some drug experts, both inside and outside of Myanmar, say the matter is not so simple -- and that the country is merely a scapegoat for the West's failed war on drugs.

"The State Department says that opium production has doubled since the junta came to power in 1988, therefore the junta is responsible," one Western official in Yangon said.

"But that's a phony argument. The key factor in 1988 was that the US decertified Burma and stopped its drug assistance. The US was providing about 80 percent of the funding for fighting drugs, so naturally when that money dried up, opium production increased. But rather than admit their error, the US is blaming the junta."

Other drug enforcement officials agree. "The Burmese were extremely cooperative with US law enforcement during the time I was there," said Barry Broman, who spent two years at the US embassy before retiring last year. "They provided major assistance. The problem was the limited amount of assistance we could give the Burmese."

Broman, who spent several decades investigating the narcotics trade in Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam before being posted to Myanmar in 1994, is one of America's most knowledgeable experts on the complex world of Asian drug trafficking.

"There are a lot of accusations that the military is involved in narcotics, but no one's produced any evidence - so where's the smoking gun?" he said, during a recent trip to Yangon.

"In my experience, the trade is not institutional in Burma. That's not to say that people aren't profiting - there's indirect profiting from the narcotics trade. But across the border, you find Thai politicians and generals in bed with the traffickers. That's not the case here."

Khun Sa But critics like Albright point to the new role that former drug lords like Lo Hsing Han and Khun Sa are allegedly playing in the Myanmar economy. Myanmar's refusal to extradite Khun Sa to the US, they said, is proof of its complicity in the drug trade.

Broman takes a different view. "On their own, the Burmese effected the capture of Khun Sa," he said. "They made a major dent in the drug trade, and we gave them no credit.

"The human rights people say they cut a sweetheart deal, but I don't believe that. In the US, we call it a plea bargain. And in this case, justice was served, because Khun Sa is out of the drug business. And that means 12,000 armed men [soldiers in Khun Sa's army] are no longer in the drug business."

Moreover, said Broman, it's unlikely that Khun Sa is as rich as many people assume. "It's a mistake to think of him as a megabucks guy, like the Columbian cocaine lords," he said.

"With cocaine, you have cartels that control everything from the coca fields to the dealers in New York, so the profits are huge," he explained.

"But unlike cocaine, heroin changes hands many times before it gets to the buyer. Khun Sa would buy the opium from producers, then process it and sell it to a politician or a general in Thailand, who would sell it to someone else in Hong Kong or Vancouver. The big profit is all outside Asia."

Myanmar government officials also discount the idea of drug lords as the new economic kingpins. When asked how much money Khun Sa was pumping into the economy, one officer from the Defense Ministry just laughed.

"They cost us money!" he said. "We have to support all those former Mong Tai army soldiers. After Khun Sa surrendered, they were on their own - we gave them money and resettled them. We don't want to fight them anymore, so we have to find something else for them to do."

What Western critics fail to understand, a number of diplomats and drug officials say in Yangon, is that the opium-producing areas are controlled not by the junta, but by armed ethnic insurgent groups along the border, including the Wa, the Kokan and the Shan.

The military is primarily interested in exerting political control over these areas, so has had to come to political settlements with the insurgent groups who have traditionally funded themselves with drug profits.

"These guys were shooting Burmese for a living," said Broman. "The drug profits buy bullets that kill Burmese soldiers. So it's in the Burmese interest to control drugs."

But to get rid of the existing opium economy and replace it with something new, time is needed. "The US wants an instant solution to the problem, but that's not realistic," said one drug expert in Yangon.

Is Myanmar's anti-narcotic campaign real, or just an exercise in public relations? Broman and others have said it's real, and is now getting encouragement from an unexpected source.

"The Chinese are putting pressure on Burma," he said. "China has a growing addiction problem, and they've told the Burmese they want them to get a handle on it. China and the US both have the same message," he added, "but the Chinese are doing a lot more in terms of helping."