The Next War in Vietnam

By Stephen Brookes • Insight • February 3, 1992

______________________________________________________________________________

It's just after dusk on a Thursday evening in Saigon, and the rooftop terrace of the Rex Hotel -- a favorite watering hole for foreign businessmen -- is starting to fill up. A warm breeze ruffles the animal topiary scattered around the edge of the roof, carrying snatches of conversation from table to table. "They want two and a half million, can you believe it? Upfront, yes! In dollars!"

Consumerism rising in Vietnam Photos by B. CabeThe Vietnamese waiters bustle back and forth with glasses of Heineken beer, Suntory whiskey and Johnny Walker Black Label, skirting the two 10-foot-high plaster elephants, the hanging parrot cages and the statues of naked maidens. "Sure, sure, but you've got to figure in packaging costs." The accents are Australian, French, German, Chinese. A moth-eaten stuffed bear, rearing on its hind legs, bares its fangs over by the bar as a cluster of Japanese businessmen, chattering happily, find a table and sit down.

Michael Gebbie, the director of a Hong Kong-based investment company called Pacific Transactions, takes a long swig of his Tiger beer and looks around the terrace. "It's become a cliché, but it's true: Vietnam is the last frontier," he says. "And it's filling up with cowboys."

After 16 years of economic stagnation, archaic politics and global isolation, Vietnam is taking a headfirst leap into capitalism, determined to claw its way into the global economy. With a per capita income of only $200 a year, Vietnam is still one of the poorest countries in the world. But trade with the West is surging, and with its mostly-unplundered natural resources, cheap labor force, stable and pragmatic government, fantastic beaches, about 68.5 million consumers, prime geographic location and unexplored opportunities, the country is being overrun by a stampede of foreign investors, advisers, traders, oil explorers, real estate developers and entrepreneurial adventurers of every stripe who think they've discovered the world's next moneymaking hot spot.

Forget about Eastern Europe, they say; strictly a basket case, and going to stay that way. The fastest growing part of the world is Asia -- and in Asia, the place to be is Vietnam. It's starting from point zero, which means it could grow much faster than overheated economies like Thailand's, and while big profits may still be years away, long-term investors will make out handsomely. With the big capital deposits in Hong Kong, Tokyo and Taipei looking for somewhere to flow, Vietnam is dangling as many lures as it can. And people are getting hooked.

"Given where it is, what it's doing and what it has," says Gebbie, "this place can't lose."

There's just one hitch: The United States clamped an almost total embargo on trade and investment in Vietnam in 1975, and it has pressured other countries to abide by the embargo since 1978, when Vietnam invaded Cambodia to kick out the Khmer Rouge. The embargo has squelched large-scale investment from countries that don't want to alienate the United States and has kept Vietnam cut off from development aid from the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank.

Washington drew up a road map for normalizing relations in April, calling for Hanoi to bring its client government in Cambodia to the negotiating table and to provide more information on American soldiers still unaccounted for, and there are indications that the embargo may be lifted soon.

But even if it were lifted tomorrow, say some investors in Vietnam, an opportunity has already been squandered. With Japanese, Australian, Hong Kong, Taiwanese and European investors poised over the juiciest investments, Washington may have dealt U.S. business out of the hottest new game in town.

To walk through the streets of Saigon (only party hacks call it Ho Chi Minh City anymore) is to walk through a caldron of change. By 8 in the morning, the old colonial tree-lined avenues, virtually empty just a few years ago, are clogged with a raucous, nonstop sea of traffic: Young men on Japanese motorcycles bluster their way through intersections, oblivious to stoplights, while groups of gray-suited Japanese businessmen dodge minivans packed with German tourists.

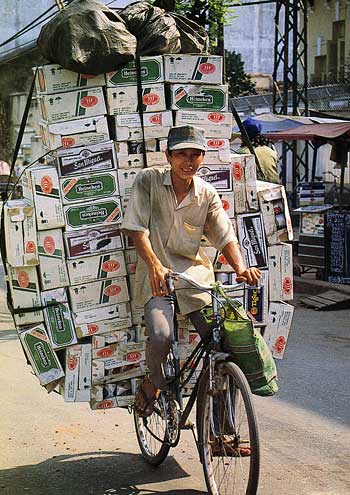

Decades-old Peugeots and Chevys, kept up with meticulous care, vie for road space with Russian Volgas, while peddlers with carts of bananas and peeled coconuts push past the ubiquitous pedicabs called "cyclos." Bicycles piled high with sacks of rice and bundles of fabric jostle along unsteadily. From time to time, like visitors from a more innocent era, elegant young women wearing the traditional white ao dai delicately thread their way through the traffic, wearing elbow-length gloves to protect their skin from the harsh sun.

The sidewalks, meanwhile, have become teeming mazes of hawkers, who crouch over their trays of herbal medicines, Russian watches, acupuncture pins, seashells, cartons of Marlboros and cans of Coke smuggled in from Thailand, condoms, week-old copies of Paris-Match, East German surgical supplies, Yamaha synthesizers, handmade lutes, even T-shirts that read, "Born and Bred in the USA."

In the expensive antique shops on the street now called Dong Khoi (the elegant old Rue Catinat), there are ivory cigarette holders, Chinese military binoculars and Zippo lighters inscribed by American GIs. Record stores stock CDs of Bon Jovi, Duran Duran and Rod Stewart, and bookstores sell Vietnamese translations of everything from Neil Sheehan's A Bright Shining Lie to a half dozen Danielle Steel romance novels. (You can even get Alexandra Ripley's sequel to Gone with the Wind -- just ask for Cuon Theo Chieugio.)

In Saigon, a building boomThe T-shirt sellers in front of the presidential palace brandish a familiar face: "Uncle Ho!" they shout to foreigners. "Very cheap! " High overhead, the billboards that sprout from the top of almost every downtown building scream Minolta, Kenwood, Hitachi and a slew of other foreign names. In the doorways below, women squat over small fires in oilcans to stir pots of chicken and vegetables to sell, while the city's lepers, their tin cups clenched against their chests, beg for coins.

The surge of foreign investors has spawned whole new industries, as well. There are more than a dozen karaoke bars in downtown Saigon, for example, to cater to the resident Japanese contingent, while European expatriates mingle with the hipper set of Vietnamese in the always crowded Apocalypse Now bar (just around the corner from the Hambugo Caliphonia restaurant). The infamous Maxim's nightclub on Dong Khoi has reopened as a restaurant, but the strip shows of the 1960s have been replaced by a bored pianist playing Beatles tunes, accompanied by an all-girl string section.

Even the skyline has changed; at the edge of Hero's Square along the riverfront sits the Australian-built, Japanese-owned Floating Hotel (rooms start at $175 a night), where a Filipino band in the lobby bar sings note-perfect renditions of Western songs like the Joan Jett hit "I Hate Myself for Loving You." The famous open-air terrace cafe of the Hotel Continental, where Somerset Maugham and Graham Greene sat and wrote their novels, has just been transformed into a glassed-in pizzeria called Guido's. "Come to Ho Chi Minh City," the official SaigonTourist guidebook cheerfully urges, "a town endeared to the search of its identity!"

For Saigon -- in fact, for all of Vietnam -- that search is moving into high gear. Since the late 1970s, when it became painfully clear that Soviet-style, centrally planned economic policies were creating a quagmire, the country has been revamping its political, economic and foreign policies at a pace that in some ways has outstripped the changes in Eastern Europe. The "American war," as it's called here, had left the country economically ravaged, and the aid and subsidies that Moscow provided were nothing more than Band-Aids.

Putting together a unified, national economy proved daunting. Not only were Hanoi and the newly renamed Ho Chi Minh City at opposite ends of the country, they were (and still are) culturally divided as well. "The people down here never really adopted socialism," says a Singaporean who has lived in Saigon for several years. "They just remember it as a time when the country went dead."

By 1979, with rigor mortis setting in, Hanoi was forced to act. It abandoned collectivized agriculture, allowing farmers to lease land from the state and sell produce at market prices. The results were remarkable: The country went, almost overnight, from being a net importer of rice to a net exporter. Encouraged, Hanoi began to experiment with similar incentives in industry (allowing factory managers to pay piece-rate wages, for example), and in 1986 it formally legalized private economic activity.

It was the beginning of doi moi, economic reform, and the policy picked up speed throughout the late 1980s as Hanoi took more and more steps toward a market economy. Some price controls were lifted and the banking system was overhauled. By 1989, Hanoi dropped overall central planning and began cutting away, or abolishing entirely, subsidies to state industries. A slew of market-freeing measures followed: Citizens could buy and sell gold, companies were allowed to export and keep the hard currency earnings, managers were given free rein in their factories. Doi moi was emerging, the World Bank noted admiringly, as "a bold economic reform that puts Vietnam in the forefront of socialist economies attempting to rejuvenate their economies."

The pace of the reform was, inevitably, sped up by the collapse of socialism in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. Until 1989, Hanoi had been able to prop up the economy with huge shipments of gasoline, fertilizer, steel, cotton and other products from the Soviet Union, provided at "friendship" prices, and aid of some $1.1 billion a year. But by 1991 Moscow's pockets were so empty that the shipments dropped by half -- and had to be paid for in hard currency at market prices. Moreover, Vietnamese workers in Eastern Europe, who had been sending home as much as $150 million a year, were being repatriated. To cap things off, Moscow also began demanding that Hanoi repay its 9 million-ruble debt -- in hard currency, naturally.

The rejuvenation hasn't gone completely smoothly. "There isn't any model for us to follow -- no communist country has shifted to a market economy," says Vu Huy Hoang, a deputy director of the State Committee for Cooperation and Investment. "But we're finding our way, slowly." Signs of economic vitality and stability are growing. The government's $200 estimate of per capita income is probably an understatement, since so much activity takes place outside the official economy. Inflation is running at 70 percent a year, but that is a vast improvement over the triple-digit inflation that rampaged through most of the 1980s, and the government is determined to bring it down to 30 percent this year

Matthews: Everyone wants a market economyIn discussions with top government officials, bankers and businessmen, one theme comes through: an absolute commitment to seeing a market economy evolve, and quickly.

"I don't think there's any doubt in anyone's mind that the market economy is the way to go," says Eugene Matthews, a young American investment adviser who lives in Hanoi on a student visa to avoid the restrictions of the embargo. "And not just among the leaders. You talk to the people in the markets, who couldn't sell their produce a few years ago, and they're very enthusiastic about the new system. They like the benefits, and they like that they're allowed to operate the way they want."

Aside from promoting private industry inside Vietnam, Hanoi is also making an all-out effort to attract foreign investors -- and the technology, capital and expertise that come with them. In 1986, it baited the hook with one of the most liberal foreign investment codes in the developing world: Foreigners are allowed to own 100 percent of any companies they set up (although they're encouraged to form joint ventures with state-owned companies) and can invest in any enterprise except those related to national security or deemed "socially incorrect," like gambling.

Investors are free to repatriate earnings and capital, with a moderate withholding tax of 10 percent. And while corporate income is taxed at a rate of 20 to 25 percent, the government will bargain. In fact, say investors, everything is negotiable, from taxes to land leases (normally 20 years) to wages (officially, foreign companies are required to pay workers no less than $50 a month). Hanoi is also setting up export processing zones where investors will pay less than 15 percent in taxes, be free from all import and export levies, and get breaks on customs, visa and bank formalities.

"We're always talking with foreign businessmen to see what they want," says Hoang of the cooperation and investment committee. "We're very much open to suggestions."

Despite the incentives, investors are wary. As of October, about 330 investment licenses had been granted, mostly for industrial production, oil and gas, agriculture and tourism, representing some $2.47 billion in foreign investment. "According to my estimates, in order to be able to take off in the future, investment should be at least $2.5 to $3 billion a year," says Nguyen Xuan Oanh, a Harvard-trained economist who advises the government on economic policy. "Now, $2.4 billion in two years is too small; we've got to do better than that."

Investing in Vietnam is not for the fainthearted or for anyone seeking quick profits. The investment code that looks so inviting on paper is not matched by ease in the day-to-day vagaries of doing business. Just signing a contract, for instance, can involve negotiating a maze of interlocking bureaucracies and conflicting regulations. Modern office space is almost unobtainable, and it costs an estimated $100,000 just to get a lease, renovate the building and make it operational.

Power supplies are erratic; some sections of Saigon and Hanoi have electricity only four or five days a week, and telex and fax services are unreliable and expensive. Visa and customs formalities can be agonizingly slow, and transportation is atrocious: Roads and railroads are a wreck; Vietnam Airline's fleet of narrow-body Tupolev-134s has a total capacity of only 1,400 passengers. Water supplies are unsanitary, malaria is pandemic, communications are comically unpredictable (two people trying to call an office at the same time may find themselves connected to each other, for example), and equipment in factories, especially in the North, is often decades out of date and in poor condition.

Moreover, the rules of the game still haven't been clearly established. Theoretically, an investor can make contact with a company, agree to a joint venture and get a license from the State Committee for Cooperation and Investment. But in practice, things are more complicated. Investors can get locked into doing business with a web of companies under the control of a single government ministry, limiting their freedom and subjecting them to the whims of lower-level bureaucrats. And while bribery is rare, gouging is said to be widespread.

"Corruption here is nothing like it is in some other Asian countries," says a Western businessman who has been in Saigon for several years. "We've never been confronted in official business with any suggestions that we pay people off. But you are sometimes asked, officially, to pay for services which are not reasonable. It's not corruption, but it's not very ethical, either."

And the country's legal framework is still tenuous. While the foreign investment law is quite liberal, investors can find themselves strung up on a web of regulations implemented by local authorities. "A lot of the financial problems people get into stem from the legal problems," says one European adviser in Hanoi. "Contracts can suddenly change, unilaterally. And although Vietnam has agreed to go to outside arbitration panels to settle disputes, the final guarantor of the agreements is Hanoi. So...."

Vietnam's isolation has left its mark as well. "You're dealing with highly intelligent people who are well-educated and eager to learn," says one European businessman. "What they lack is the understanding of Western business practices and concepts. And that leads to indecisiveness; they'd rather not make a decision than make a bad one. They're lovely people, but they don't understand the idea of time being money."

Good management is missing, says OanhSome Vietnamese agree. "The success of doi moi has been uneven, primarily because of the lack of competent managers," says government adviser Oanh. "Bankers, managers, the people who can fill the key positions - these are very much missing at the moment."

In fact, the old military cadres who made their mark in wartime against the Americans, the Khmer Rouge or the Chinese were often rewarded with directorships of state companies. "You'll sit down at a meeting with the managers of a Vietnamese company, and then the director will make his appearance," says Gebbie of Pacific Transactions. "And everybody will roll their eyes and look down at the table while he makes a few comments. After a minute or two of this, he's conveniently called away to take a telephone call. And then you can start discussing the project."

In spite of the hazards and hassles, though, money is still coming in. Taiwan has been the most enthusiastic investor. It has the largest single joint venture in the country -- worth some $88 million -- and a total of 39 projects worth nearly $538 million are under way. Some $350 million has come in from Hong Kong investors, $280 million from Australians and $273 million from the French, who have been putting money into textile mills, oil exploration, hotels, auto assembly plants, seafood processing and anything else that seems promising. Investment companies like Pacific Transactions and Inchcape Vietnam are setting up shop, and international banks are opening branches. Investors have come from Britain, Denmark, Hungary, Argentina -- 31 countries in all.

But the country that is having the most impact is Japan. Tokyo has been paying lip service to the American embargo and has not provided any official aid, but neither has it forbidden its businessmen from trading or investing with the Vietnamese. As a result, tens of thousands of Japanese have been scouting the territory for the past several years, looking for investment opportunities, signing agreements for joint ventures and waiting until the embargo is lifted. Their ranks are growing: The number of entry visas granted to Japanese businessmen doubled last year, to about 15,000. With $103 million committed so far, Japan is only the ninth-largest investor, but trade between the two countries shot up to an estimated $1 billion last year, making Tokyo Vietnam's largest trading partner. Official development assistance from Japan's government likely would unleash a flood of investment.

In fact, the Japanese presence is so strong that it has made other investors nervous. There are huge billboards advertising Japanese electronics and automobiles all over Saigon and Hanoi, and companies like Hitachi (which opened a showroom in Saigon in November) are praising Vietnam as "the market of the future."

"The day after the embargo is lifted, you will probably find that the Japanese have sewn up the country," says a European businessman in Saigon. "They've been preparing for that and spoiling the prospects for others to do business in the meantime. You just can't help but feel that the Japanese are not able to put their money where their mouth is, that they're just using delaying tactics until the embargo is lifted, hoping that opportunities will become available. So it's detrimental to the country's growth."

Japanese businessmen in Saigon; other investors are waryIn fact, Japan-bashing is almost a full-time sport among non-Japanese investors. They complain that the Japanese have been pushing up rents to ludicrous levels -- leasing unrenovated villas in Hanoi for as much as $30,000 a month, for example -- and accuse them of taking advantage of the lack of business sophistication among the Vietnamese.

"This town is full of big-money cowboys;' says investment adviser Gebbie. "They'll draw up a $25 million project for a new building, get a license from the government to use the land and then disappear. They can't pull the financing together, but they've tied up the property. So when somebody else comes along with a serious proposal -- say, renovating a building already on the site for $2 or $3 million -- the Vietnamese will turn it down. Why should we do that, they ask, when these other guys want to invest $25 million? So nothing gets built. The cowboys scare the serious money away."

Oanh agrees. "It's quite simple to check on peoples' credit ratings," he says. "But most of the leaders are quite green at the game. They don't know how to do it, so they sign everything and anything, and it turns out to be a raw deal."

On broad, leafy Dien Bien Phu Avenue in Hanoi, just around the corner from the gray marble mausoleum that holds Ho Chi Minh's body, sits an elegant old villa housing Vietnam's Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In a second-floor reception room looking out over what must be one of the only statues of Lenin left standing in the world, Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs Le Mai is eager to discuss the American embargo. As head of the delegation that met in November with Richard Solomon, U.S. secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs, he seems optimistic that relations will be normalized soon.

"I told Mr. Solomon, you have the American road map, and I have the Vietnamese shortcut," he says, laughing. "So let's put them both on the table and talk."

Normalizing relations with Washington has been at the center of Hanoi's foreign policymaking for more than a year. While the Vietnam War still seems close to many Americans, the Vietnamese have been through two border conflicts since then, first with the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, then with China. Americans are greeted almost everywhere in Vietnam with genuine warmth and interest. Until the embargo is lifted, economic recovery can never really take off.

"It was our initiative to normalize relations with the United States, you know," says Le Mai. There are two official interpreters in the room, but as he speaks perfect English, they wait quietly, listening. "We know we are a small and humble country, so we should make the first step."

Signs of a shift in U.S. policy are multiplying. Washington lifted its embargo against Cambodia on Jan. 4, and during a January visit to Hanoi Rep. Stephen Solarz, the New York Democrat who heads the Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Asian and Pacific Affairs, said the embargo against Vietnam might be lifted this summer or fall. While U.S. airlines are still forbidden to fly to Vietnam, Washington lifted the ban on U.S.-organized tours in mid-December.

There are also signs that America's allies are growing increasingly impatient and that international support for the embargo is crumbling. Japan's influential Ministry of International Trade and Industry has indicated it is close to supporting Japanese investment in Vietnam, and grants and soft loans are flowing in from a number of countries, including Australia, Italy and France.

"The embargo is like gunship diplomacy," says Le Mai. "It's out-of-date and doesn't fit the international situation today, which is the world of interdependence. That's why all people in Southeast Asia would like to see U.S.-Vietnamese relations normalized -- it would be beneficial to all."

Some observers, like George Carver of the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, are skeptical. "Vietnam is never going to be an economic tiger, or anything but a basket case, unless it forswears Marxist ideology, which is still the dogma of the country," he says. "And there's a lot more in normalizing relations for them than there is for us. So what's the rush?"

But to others, there's no more time to waste. "The Japanese may not be the largest investors now, but I guarantee you that one year after the embargo is lifted, they'll be No. 1," says investment adviser Matthews. "Do we want a country like Japan, which is our economic competitor, to gain an economic leverage by having access to cheap labor and a lot of natural resources? Do we want them to have that advantage over us? My answer to that is, no. Definitely, no."

References (8)

-

Response: get new year 2017 wishes

Response: get new year 2017 wishes -

Response: Online Calendar

Response: Online Calendar -

Response: best birding binoculars

Response: best birding binoculars -

Response: survival & binoculars guide

Response: survival & binoculars guide -

Response: Everleigh Abra

Response: Everleigh Abra -

Response: Happy New Year 2023 Quotes

Response: Happy New Year 2023 Quotes -

Response: 1,'.)(("'",1

Response: 1,'.)(("'",1 -

Response: Enterprise software management toolExplore the Best Enterprise Project Management Tools. Get insights into the leading Enterprise PPM software for strategic project portfolio management optimization.

Response: Enterprise software management toolExplore the Best Enterprise Project Management Tools. Get insights into the leading Enterprise PPM software for strategic project portfolio management optimization.

Reader Comments