In Global Trade Talks, a Fight Over Farming

By Stephen Brookes in Montreal • Insight • January 9, 1989

_________________________________________________________________________________

They were supposed to reap an "early harvest" of tangible results, but when the world's trade negotiators ended a four-day meeting in Montreal in disarray Dec. 9, it looked as if the seeds had been sown for a transatlantic punch-out over farm trade instead. Emerging red-eyed and rancorous from a grueling 36-hour session, U.S. and European negotiators admitted that they were still stalled over whether to "eliminate" or merely "reduce" the billions of dollars spent every year to subsidize their farmers.

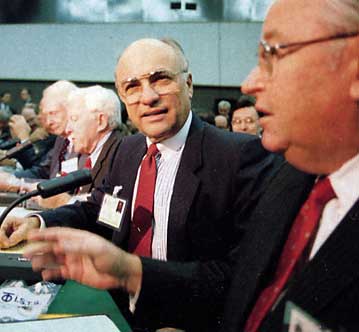

Yeutter (l) and Lyng talking tough on trade Stephen BrookesThe stalemate in the midterm review of the Uruguay Round of negotiations under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade infuriated delegates from the rest of the world. "The United States and the European Community really deserve each other," said Australia's trade minister, Michael Duffy. "They're a pair of rippers."

Angry that neither side had agreed to budge, five Latin American countries withheld their approval of the 11 other agreements that had been reached during the talks, derailing the confab and forcing the United States to call an emergency, high-level meeting for early April to get through the impasse. With only a few months to sort out the mess, negotiators are less than optimistic; Europe and the United States, one warned, are "staring down the barrel of a trade war."

No one really expected the 96 members of GATT, the body that sets the rules for international commerce, to make dramatic progress on the ambitious agenda set when the talks were launched in September 1986. Montreal was to be merely a midpoint assessment in the four-year process -- a time to take stock, to rally political will and to set out a blueprint for the rest of the negotiations. The Uruguay Round, the eighth such set of negotiations since GATT was formed in 1947, was supposed to bring about a "new multilateralism" in world trade, to tackle entirely new areas of international commerce such as services, investment and intellectual property and to improve the way the GATT system works.

In fact, some progress, if undramatic, occurred in many of those areas. Most of the results were procedural -- oil in the trade machinery rather than solid reductions in trade barriers. "There's nothing there that would cause the CEO of any major American corporation to look up from his cup of coffee," says Gary C. Hufbauer, a professor of international financial diplomacy at Georgetown University.

But negotiators did agree to lower the industrialized countries' barriers to imports of tropical products, an agreement important not so much for its economic value (it covers only about 0.5 percent of world trade) but because it brought the developing countries fully into the GATT process for the first time. Tentative agreements were also reached on reviewing members' trade practices (which should build pressure for more liberal policies) and on a framework for discussing tariff reductions.

The Montreal talks also brought about a consensus on negotiating a multilateral framework for services. Such a deal has been high on the U. S. agenda from the beginning; once defined as "things you can buy and sell but can't drop on your foot," services now account for as much as 25 percent of international trade, and with the exception of a few areas such as transport and communications, are completely outside of international rules. Countries like the United States, with advanced economies in which services play a large part, stand to gain most from the agreement and hope that implementing a legal framework in GAFT will give the same boost to their service industries in the 1990s that reducing tariffs did for manufactured goods after World War 11.

But none of these agreements will amount to much in the absence of one to free up trade in agriculture, which makes up about 14 percent of world trade. Global farm markets are massively distorted by the $200 billion that Japan, the United States and the European Community spend every year to support farm prices, prop up farmers' incomes and subsidize exports. Not only do these programs cost consumers an estimated $1,000 a year each in taxes and higher food costs, they hit governments in the developing world, which cannot afford to spend at the same rate, with an estimated $26 billion annually in lost export sales.

Subsidies linked to production lie at the heart of the problem. They foster overproduction, creating gluts on world markets that in turn lead to export subsidies, import restrictions and further trade distortions. Recent advances in agricultural technology and productivity only compound the problem. But programs to insulate farmers from the ups and downs of the market have become so deeply ingrained in most industrial societies that, despite their costs, they are almost impossible to dismantle. The United States and the European Community have exempted their farm programs from GATT rules for decades, and attempts to address the problem in previous talks have gone nowhere. This made it all the more dramatic when the Reagan administration proposed in July 1987 that Europe, the United States and Japan eliminate in tandem all trade-distorting farm subsidies by the end of the century. It was a bold, imaginative gesture -- too bold for both Europe and Japan, where it was widely ridiculed as unrealistic grandstanding. But 13 non-subsidizing, grain-exporting countries known as the Cairns Group welcomed the proposal, cautioning only that the deadline be more flexible.

This made it all the more dramatic when the Reagan administration proposed in July 1987 that Europe, the United States and Japan eliminate in tandem all trade-distorting farm subsidies by the end of the century. It was a bold, imaginative gesture -- too bold for both Europe and Japan, where it was widely ridiculed as unrealistic grandstanding. But 13 non-subsidizing, grain-exporting countries known as the Cairns Group welcomed the proposal, cautioning only that the deadline be more flexible.

Europe's reluctance was predictable. The Common Agricultural Policy is the EC's most sacred of sacred cows; European negotiators never tire of referring to it as the glue that holds the 12-nation trading bloc together and argue that the community would effectively cease to exist if the complicated subsidization program were to be phased out. The CAP was the community's first major deal, and it has kept most of Europe's 10 million farmers, who work farms that average only one-tenth the size of those in the United States, afloat through most of the postwar period. But it has also been massively expensive, absorbing about two-thirds of the EC's annual budget, and massively wasteful: Among its most visible legacies have been the vast, slowly rotting "butter mountains" and the "wine lakes" that dot the community's economic landscape.

Europe's leaders claim that reform is under way, but the measures taken so far have been too few and too tentative to be fully convincing. Governments from London to Lisbon would welcome cutting their farm spending, but European farmers are a vocal, volatile lot whom politicians ignore at their peril. And with Greece, Spain and Portugal joining the community, their numbers have doubled over the decade.

That has made it tough for Frans Andriessen, the EC's tough-talking agriculture commissioner (who was to move to the external trade slot Jan. 6), to push forward with plans to make the Common Agricultural Policy more market-oriented. There has been some isolated movement: Dairy herds have been reduced by 20 percent since 1984, prices of main commodities such as grains and beef are slowly being brought back to market levels, and last February the bloc agreed to limit rises in overall spending on agriculture to 1.9 percent a year -- substantially lower than the 7.5 percent average annual increase since 1975.

Figures like those do not impress U.S. negotiators, who say the reforms merely freeze production at levels that already distort trade. For the moment, however, it is likely to be as far as the Europeans are willing to go. The European Community seems to be reconciled to the costs of the CAP (some $77 billion a year), and no one expects it to gracefully submit to U.S. pressure. "We are open to liberalization, but we are not prepared to discuss the complete elimination of support measures," said Andriessen, who wants moderate, concerted reform. "We in the EC have taken measures in the short term, but we want others to do the same."

That did not go far enough for the United States. U.S. Trade Representative Clayton K. Yeutter and Agriculture Secretary Richard E. Lyng refused in Montreal to accept any deal on short-term reforms before both sides had agreed to set a firm deadline for eliminating trade-distorting subsidies. "We should not be simply nibbling around the edges" of farm reform, said Yeutter, who has been tapped to serve as agriculture secretary in the Bush administration. "We've got to get to the heart of the problem."  There were other doubts about the depth of the European Community's commitment to reform. Says Daniel Amstutz, chief U.S. agriculture negotiator in the Uruguay Round, "What is frustrating is that the EC only wants a freeze and a possible rollback in internal supports. But it has said nothing about market access, nothing about export competition ' "

There were other doubts about the depth of the European Community's commitment to reform. Says Daniel Amstutz, chief U.S. agriculture negotiator in the Uruguay Round, "What is frustrating is that the EC only wants a freeze and a possible rollback in internal supports. But it has said nothing about market access, nothing about export competition ' "

As positions hardened in the final night of negotiations, Agriculture Minister Henri Nallet of France called a news conference to mock the American intransigence, challenging, "Do they want to negotiate or not?" There was a flurry of excitement at one point, as word leaked out that negotiators were thumbing through a thesaurus to find a substitute for the word "eliminate" that both sides could live with. Lyng suggested a few choices of his own: kill, end, abolish, phase out, terminate, murder. One participant muttered of the last option, "I can think of a few people he probably had in mind."

No substitute was found, and the talks broke off. Many now fear that the time to cut a deal is running short. "I'd be very surprised if the agriculture question is resolvable in this kind of time frame," says Alan J. Stoga, chief economist at the consulting firm Kissinger Associates. "We're talking about almost unimaginable changes in how the industrial world treats its agricultural sector."

Analysts are cautious about predicting in the April talks. It may be in the nature of trade negotiations that tough issues are never resolved until the eleventh hour. "The United States is playing the 'hard' role, the Cairns Group is pointing the way to compromise, and the Europeans are playing the reluctant maiden who is slowly being lured out," says Hufbauer. "I think this kind of role-playing will continue right up until the end."

With a new U.S. administration and a new EC Commission, the group's executive body, both coming into office in 1989, there may be some changes in those roles. The appointment of Carla Hills as the Bush administration's trade representative, Yeutter's shift to secretary of agriculture and Andriessen's new position as external trade commissioner could be the catalyst for diplomatic initiatives. Ongoing pressure from the developing countries and an economic summit coming up in May that is expected to concentrate on agriculture may also focus European and American minds.

For all its apparent commitment to a subsidy-free world, the United States may blink first. The Reagan administration has never completely sold the idea to either Congress or American farmers, and support for protection of one kind or another remains widespread. Some observers say the administration may have oversold its position from the beginning, first by blaming problems in the agriculture sector on unfair foreign competition, then by promising that the GATT talks would resolve the problem.

Yeutter insists that most American farmers will support the plan if it is undertaken by all the major exporters at the same time, but observers remain doubtful. "It does surprise me, the amount of enthusiasm in Washington for what is undoubtedly theoretically the correct policy, but which in practice hasn't met very many political tests," says Stoga. “And then to go to the rest of the world and say, 'We're prepared to do this, and we're going to beat you up to get you to do the same!' I don't think we're ripe for it, domestically. I'm pretty sure that the Europeans are not, and I don't see any great ground swell of reformist fervor in Japan. So where is our leverage?"

A number of U. S. farmers, in fact, find the European position rather to their liking. "There were observers at Montreal from the commodity groups who were hoping that exactly what happened would happen," says George E. Rossmiller, executive director of the International Policy Council on Agriculture and Trade. "Sugar, dairy, peanuts - they all depend on our GATT waiver."

Congress, meanwhile, appears ready to push ahead aggressively with export subsidies. Some $2.5 billion is earmarked in the new U.S. trade bill to promote farm exports through September 1989, and with talks on a new farm bill due to begin sometime in the next two years, momentum for even more spending could gather fast. The chairman of the Senate Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry Committee, Patrick J. Leahy of Vermont, has left no doubt that subsidies would be increased unless a commitment on long-term reform was reached soon. "American farmers," he told reporters in Montreal, "should not be asked to bear the burden of unfair competition."

The EC's Frans AndriessenWith Congress digging in its heels, the Bush administration may decide to backpedal to a more sustainable position. "I think agreement on agriculture is closer than meets the eye, because the position the Europeans are taking is about as far as we're ever going to get Senator Leahy and the agriculture committee to go," says Georgetown's Hufbauer. C. Michael Aho, director of economic studies at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York, agrees: "What Leahy and company were saying in Montreal wasn't a threat," he says. "That was reality."

Other factors may persuade U.S. negotiators to soften. A lower dollar has made American agriculture more competitive on world markets even without expanded subsidies, and by settling for gradual cuts in subsidies, President Bush might get more valuable progress elsewhere. "There's a trade-off for the administration," says Hufbauer. "If it narrows its focus, it can get deeper liberalization in at least a few areas -- a really substantive agreement in intellectual property, for example."

Despite the inconclusiveness of the Montreal talks, most players in the game, like Canada's minister for external trade, John C. Crosbie, insist that GATT is "alive and well, with some aches and pains.” But others see bilateral deals and "minilateral" blocs of like-minded trading partners --Europe's 1992 integration, for example, or the U.S.-Canada free-trade agreement -- as the arena in which the important trade issues of the day are being worked out. The United States has indicated that it is receptive to these kinds of special trading relationships, and Japanese diplomats have been taking soundings on the issue in Washington.

This prospect -- a world of rival trading blocs -- worries most economists, who see it resulting in higher tariffs directed toward nonmembers that would strangle world trade and derail global economic growth. It is also a path that most of the U.S. business community views with real concern. These concerns may persuade the Bush administration to soften the U.S. negotiating position in order to preserve GATT. The system may not be perfect, says Citicorp Chairman John S. Reed, "but we just don't like the alternative."