Money Laundering: It's a Dirty Business

By Stephen Brookes • Insight Magazine • August 21, 1989

___________________________________________________________________________________

They called it La Mina -- “the mine.” Almost every day, armored cars would make the rounds of a network of small jewelry stores in Miami, New York, Chicago and six other cities around the country, picking up boxes of cash. The boxes, outfitted with invoices marking them as gold and jewelry, were driven to the nearest airport, loaded up on commercial carriers and flown to Los Angeles, where they were met by more armored cars and taken to two wholesale operations in the city's jewelry district.

There they were opened, and the cash -- close to $3 million a day -- was counted and sorted on high-speed machines. Deposited into local bank accounts as the proceeds of legitimate jewelry sales, the funds were wired first to accounts in nine banks in New York, then out of the country and into secret accounts in Panama, Uruguay and Colombia before coming to rest in their ultimate destination: the pockets of Pablo Escobar Gaviria and Jorge Luis Ochoa Vasquez, the kingpins of the notorious Medellin cocaine cartel.

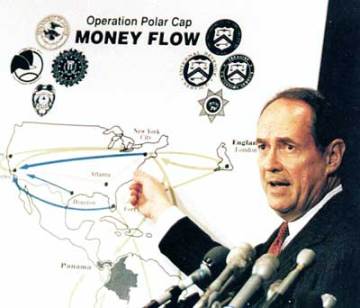

But in late March, “the mine” caved in. In what Attorney General Dick Thornburgh called "a very hostile takeover of a major money laundering operation," the Justice Department indicted 127 persons, seized bank accounts in Atlanta, Miami, New York and San Francisco and launched a suit against nine U.S. banks to recover $433.5 million in drug profits.

The 13-month sting operation, codenamed Polar Cap, was the latest and largest in a string of recent federal busts against money launderers, and agents from the half dozen agencies involved were happy about the way it turned out. "We really hurt the bad guys," says one FBI investigator. "We hurt them bad."

Putting the hurt on drug dealers by grabbing their money has become the new thrust of the war on drugs. While busting La Mina was a major coup, investigators say they are only scratching the surface of a multi-billion dollar industry. Drugs are a business -- a very big business -- and hundreds of millions of dollars in cash has to be collected and hidden away daily, until it can be disguised as legitimate income and brought back to the surface. To do that, the dealers need specialists in the fine art of changing dirty money into clean, experts who can set up veil upon veil of secret bank accounts and phony front operations, weaving a paper trail so twisted that anyone trying to follow it will be lost.

This has been a frustrating decade for the war on drugs. The invention of crack cocaine has brought a huge surge in demand, and attempts to stanch the flood of the stuff from its sources in Latin America have been disappointing. So following the money trails that dealers leave behind, and then bankrupting the dealers once they are found, is emerging as a major focus of the anti-drug effort.

Those charged with fighting the war -- the Drug Enforcement Administration, the Justice Department, the Customs Service, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Internal Revenue Service and a number of other federal and local agencies -- have been pooling resources and expertise to infiltrate and uncover the hundreds of global laundering networks that the traffickers depend on.

The FBI's David Binney"This has to be the way to go -- interdiction and eradication have been ineffective," says David G. Binney, chief of the FBI's drug section. Salvatore Martoche, assistant secretary of the treasury, agrees. "The bad guys will put a lot of distance between themselves and the drugs," he says, "but very little distance between themselves and their money."

The amount of money that fuels the drug trade is staggering. Some $300 billion is spent on drugs in the world every year, substantially more than China's entire output of goods and services. More than a third of that is spent in the United States, and almost all of it is in cash, mostly small bills. But cash is hard to spend in any interesting amount without arousing suspicions, and it is risky to just keep around in boxes. So traffickers have to hide it (from the police and from other crooks), either by getting it into a secret bank account in an offshore haven or by making it look like legitimate income.

Drug dealers rarely wash their own money; they don't need to. A new breed of highly sophisticated specialists has come of age since the early Seventies, young financiers who know their way around the international banking world and often have well-placed contacts in the financial community. "The traffickers are good at one thing; moving drugs," says Brian M. Bruh, head of the IRS's criminal investigations division. "So they hire professionals in the movement of money who are willing to help them."

While a few are actually part of the trafficker's organization, most are independent operators who hire out, often to competing drug lords. "Different drug operations, as many as 10 or 12, will share the same money launderer," says Michael Omdorff, head of the DEA’s financial investigatons section. “And in most cases, they never lay eyes on the drugs.”

The launderers range from what one IRS official calls the "cash-and-carry types, who pack up suitcases with their clients' money and head for the nearest offshore bank," to elaborate operations with money wiring facilities, telex machines, automatic bill-counting equipment and an international network of legal and financial experts. And while some operations (like Polar Cap's La Mina) involve hundreds of people, others are streamlined and harder to detect.

"We've had people testify that they could launder a million dollars a day fairly easily by setting up an operation of five or six people and a half dozen banks," says Omdorff.

Attorney General Dick ThornburghThe rewards can be fantastic, even for smallish operations. Roberto Milan-Rodriguez, a 37-year-old accountant who ran a laundry for years out of his small Miami office, was picked up in 1983 packing 20 boxes of cash, some $5.4 million in $100 bills, into his Lear jet at Fort Lauderdale Hollywood International Airport. Searching his home and office later, investigators found automatic weapons, 64 pounds of cocaine, $45,000 in counterfeit money, $350,000 worth of electronic security equipment and the records of a network that laundered funds for more than a thousand clients.

Milan-Rodriguez later admitted washing as much as $200 million a month through Panama (with the paid cooperation of the country's leader, Gen. Manuel Antonio Noriega) and was making $300 million a year in profits - all while running a respectable accounting service.

Aside from knowing their way around both the financial and drug communities, the launderers do not fit any particular pattem. There was Isaac Kattan Kassin, who laundered $100 million a year in the late Seventies for a dozen Latin drug cartels using a carefully cultivated network of crooked bank employees; Jesus Anibal Zapata, convicted in April last year on charges of laundering more than $45 million for Escobar; Terry Trupp, the mayor of South Lake Tahoe, Calif., arrested in the spring for running a ring that, as he bragged to undercover agents, had been around for 20 years. Three former DEA agents were charged in November with laundering $608,000 in drug money. Even a former Cabinet member has gotten into the act: Robert B. Anderson, who was Eisenhower's second-term secretary of the treasury, pleaded guilty in 1987 to operating an offshore bank designed to evade income taxes; the government claimed that his partner had used the bank to launder drug money.

The launderers have been getting more sophisticated because the government has become more determined to catch them. Starting in 1970 with the Bank Secrecy Act (which lay near-dormant for more than a decade) and the subsequent Money Laundering Control Act of 1986, the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988 and enhanced use of the Racketeer-Influenced Corrupt Organizations statute, Washington has been developing a systematic attempt to track the flow of large cash deposits and international money movements.

Tracing the flow of drug money through the banking system "is like any other asset-tracing procedure: You search for the ultimate source of finds coming into the bank and the disposition of funds leaving the bank," says Charles Morley, a former IRS investigator who now heads the CGM consulting group. "Both ends of the transaction can lead you to hidden sources of income, hidden assets, previously unknown witnesses and other principals."

The linchpin of the legal framework is a rule that all financial institutions (including banks, credit unions and savings and loans) must file a Currency Transaction Report with the IRS on any cash transaction of $ 10,000 or more. That puts pressure on the dealers, who now have to scurry around making lots of $9,999 deposits instead of one big one. (Traffickers beware: Banks are also required to watch for - and report -- just such suspicious transactions.)

But the rule also catches them at the last really vulnerable point in the laundering chain; once deposited in the system, money can be wired almost anywhere in the world in a matter of hours, leaving behind a trail so thin it is almost impossible to trace.

Not only banks are being recruited into the war on drugs. To make it harder for traffickers to turn drug money into cars, jewelry, real estate and other big-ticket items, some businesses are also now required to report large cash deals, and it is a felony offense not to file. It is also a felony to knowingly do business with drug dealers or to cooperate with them by structuring payments to get around the reporting requirement. If a car dealer, for example, takes $9,500 in cash and a check for the rest from a client who turns out to be a drug dealer, he is in big trouble.

Bankers grumble about the new regulations, and the more stringent ones they fear are on the way. But they have become much more obliging since the early Eighties, when a wave of investigations into corrupt bankers rocked the industry. Official implications that American banks were holding hands with drug dealers (summed up in a 1982 remark by Customs Commissioner William von Raab that some banks had "a sleaze factor higher than their interest rates") stung badly. Anxious to turn their image around and fearful of the penalties ($10,000 per shady transaction, per day, per place of business) that they face under the new legislation, the banks have been eager to comply. Currency Transaction Report filings shot up from almost none at the beginning of the decade to more than 7 million last year.

William von Raab“The banks have really cleaned up their act,” says von Raab, who retired as customs commissioner last month. "When I made that speech seven years ago, the banks felt they were immune, that they were providing a service and had no responsibility to know their customers. We changed their mind." In fact, it was apparently a bank tip-off that led to the arrest of 16 persons in May on charges of laundering $ 100 million a year for a Colombian drug cartel headed by Jose Santa Cruz Londono, thought to supply about 80 percent of the cocaine that reaches New York.

But eager to forestall efforts to lower the reporting threshold or put new requirements on wire transfers, the American Bankers Association formed a task force on money laundering in March, and has appealed for record keeping and reporting regulations to be simplified. "There is no question but that the banking community needs to assist the govemment in keeping control over cash, and we're glad to cooperate," says Earl Hadlow, chairman of the task force, who adds that transaction reporting requirements have cost his Florida bank millions of dollars. “But we need a system that banks can comply with and that won't result in an inundating flood of paper which is so overwhelming that the government can't separate the wheat from the chaff.”

Bankers also complain that they do not get enough feedback on how the information they are providing is being used. "We don't get enough guidance from Treasury," says John Byrne, the Bankers Association's legislative counsel. "I don't think we get enough on how to look out for shell cotporations. If they get a tip that money laundering is taking place in a particular area, they ought to inform bankers there."

What the banks are really scared of, though, is the employee who may not be able to resist a launderer's bribe. There have been dozens of such cases; three upper-level employees of the Great American Bank in Florida (including the vice president of the loan department) were convicted in 1985 of taking bribes not to report some 400 transactions. In a little over a year, they had laundered $94 million.

To protect themselves, most large banks have started broad training programs: When all the employees from tellers on up know what a laundering operation looks like, it gets much tougher for a rogue loan officer to bring off a scam for long.

But no system is foolproof against greed. "Human nature being what it is, if you look hard enough you're going to find someone who has a price. And, unfortunately, in the narcotics business the wages are extremely high," says consultant Morley. "There are some 15,000 banks in the country, and that means tens of thousands of people working for them," explains the IRS's Bruh. "Where there's this kind of money, people will be corrupted."

As banks in the major urban areas -- especially the key drug distribution centers of Miami, Los Angeles and San Antonio, Texas -- get more sophisticated, launderers are heading farther afield in the search for anonymity.

“Some of the people in the small towns don't perceive this to be a major problem yet," says Charles Intriago, publisher of the newsletter Money Laundering Alert. "But they should. The Laundromat of choice is the small bank in the small city."

But no amount of training will stop laundering in a bank that is owned by the launderers themselves. “There are major launderers who have bought banks,” says Morley. “How hard is it to do? You just put a front operation in." The IRS is investigating a number of banks (it won’t say how many). And experts admit that, for a launderer, buying a bank makes sense: “It's what I would do,” says Charles Saphos, head of the Justice Department's narcotics section.

While law enforcement agencies give the banks high marks for their new willingness to cooperate, they are pushing for legislation requiring the banks to report large or suspicious international wire transfers. That is much more complicated than reporting cash deposits, and it worries the banks. They argue that the huge amounts of money that flow in and out of the United States, an estimated $200 billion every day, make reporting almost impossible. Trying to trace even the biggest current of drug money through an ocean that size, say bankers, is doomed to fail, while saddling the banks with huge expenses.

The problem is that legal and illegal transfers look much the same. “To a government agent, a transaction looks suspicious. To a banker, it looks like a normal transaction. It's a serious problem,” says Morley.

"Treasury has come up with four or five scenarios for what could be a suspicious wire transaction, and we have advertised those to the banking industry. But beyond that, there isn't a lot we can do," says Byrne of the Bankers Association. "Unless someone tips you off, the wire itself isn't going to give you enough information to justify a phone call to the feds."

The other stinger in the feds' arsenal is legislation allowing them to seize traffickers' or launderers' assets. Previously, only the profits (usually 6 or 7 percent of the money washed) of an operation could be seized. But under the Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984 and the Anti-Drug Abuse Act, convicted launderers can be wiped out, losing any and all assets connected with the crime.

And they have been. From $27.2 million seized in 1985, the figures have risen steadily to some $207 million last year and a projected $450 million for this year. Most of that money gets dumped in the Treasury, but more and more is getting cycled back into the fight against drugs.

The Justice Department has split more than $250 million with state and local authorities, and that could grow by another $100 million this year alone. Attorney General Thornburgh said earlier this year that he wanted to turn the profits from drug running into "offensive weapons for law enforcement."

Juarez, Mexico: Launderers often use exchange housesTo avoid getting caught and having their assets turned against them, the launderers have been working out ways to get their illicit funds into the banks without setting off the reporting alarm. The most basic way is simply to break large piles of drug cash into lots of little piles, small enough to slip under the reporting threshold, a process known in the trade as "smurfing." A trafficker will dispatch his couriers, the “smurfs”, to different banks to buy cashier's checks and money orders in values less than $10,000, which are then delivered to another agent who deposits them in one of the trafficker's accounts.

Bigger banks such as Bank of America, which has some 900 branches around the country, are particularly vulnerable, since smurfs can make deposits into the same account from different branches without attracting attention. (Bank of America is said to be more alert now than it was in 1986, when it was fined $4.75 million for failing to report 17,000 cash deposits and transfers.)

Smurfing rings come to light regularly The IRS busted a typical one in 1987, when it got a tip that a certain Guillermo Garces was buying money orders with cash every day from as many as 13 banks in Florida. Each order had been made out for exactly $1,980: $2,000 minus the one percent smurfer's fee.

A search of his home turned up $900,000 in cash hidden in mirrored planters, as well as instructions, rules, route maps and monthly "travel vouchers" for his assistants. Eight members of the ring were finally convicted on felony charges.

The fact that such rings exist does not bother federal investigators: Keeping a small army of couriers on hand raises both the dealer's overhead and his vulnerability. Says the Justice Department's Saphos, “it raises the chance of getting a dissatisfied employee who'll flip for us.” So dealers, looking for more sophisticated systems, are turning to securities brokerages, currency exchanges and commodity firms.

They are finding plenty who will play along. One brokerage, American Investors Inc., was found guilty in 1987 of conspiracy and failing to report $2.5 million in cash it passed through the accounts of dead or fictitious people in order to conceal its owners. And in May last year, E. F. Hutton & Co. Inc. was fined $1 million after pleading guilty to charges it had laundered $1.5 million in cash between 1982 and 1984 for some of its clients, said to be members of organized crime.

Few stones are left unturned in the search for the perfect laundry. "Drug dealers are starting to use businesses you wouldn't expect laundering to go through, like precious metals," says Clifford Karchmer, associate director of the Police Executive Research Forum in Washington. “We'll probably find that a trend is developing in the use of commodities firms, as in Chicago, or anyplace where the haystack is so enormous that finding the needles in it becomes almost impossible.”

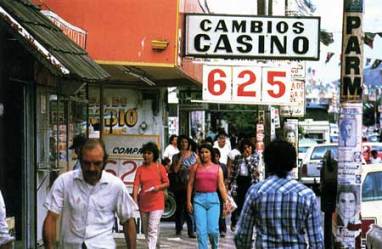

Traffickers are also making extensive use of dozens of the international currency exchange houses that dot the border between the United States and Mexico, says the DEA. Seven of them were charged in December with laundering $3.5 million, cooling off hot money for a hefty fee of 8 percent, and the practice is thought to be widespread.

The Justice Department's Charles Saphos“Currency exchange houses are a travesty around here,” says Saphos. “It's hard for us to criticize South American governments for having inadequate controls over their currency flows when we've got unregulated currency exchanges all up and down our borders. We don't license, charter or insure them. We don't even know where they are.”

Casinos are popular, too. Huge amounts of cash move through them every day, and launderers can buy chips, redeem them later and wire the proceeds directly out of the country. One of the first international laundering rings, in fact, was run out of a casino in Las Vegas during the 1940s, where Benjamin "Bugsy" Seigel cleaned up Mafia bookmaking and prostitution profits. Investigators say that the traditional Cosa Nostra has stayed away from laundering money for drug dealers but still has powerful networks set up for its own use.

“Organized crime figures have been laundering money through casinos, labor unions and sham corporations for three or four decades longer than the drug dealers,” says Karchmer. "Their money, once it's laundered, tends to stay laundered.”

Money washers also use front businesses that handle a lot of cash, such as restaurants, bars and movie theaters, to hide dirty money by mixing it with clean. It’s easy enough to do: By inflating sales reports and expenses, or writing checks to accomplices for bogus services, a well-run front operation can launder thousands of dollars a day with little risk of detection. Almost any kind of business can be used, even professional sports organizations; confessed launderer Roberto Baez-Alcaino is alleged to have used Antillas Promotions, a Miami-based fight promotion company he owned, to wash drug money.

The stricter scrutiny on the banks and the increased pace of federal sting operations have made traffickers nervous, and investigators say many are just sitting on their money. That's risky: Drug dealers need to have some cash around to pay off suppliers and meet day-to-day expenses, but an apartment full of $20 and $ 100 bills is a tempting target for other dealers -- or any other crime figure who gets wind of it -- as well as for the law.

The sheer bulk of the cash is staggering. According to the Justice Department's Asset Forfeiture Office, some $109 billion in drug money is generated every year in the United States, most sold on the street in deals for small bills, mostly twenties. That’s more than 5 billion $20 bills, weighing in at a hefty 26 million pounds.

For traffickers, it’s a major storage and transportation headache. One laundering operation was grabbed in New York earlier this year loading $19 million in small bills onto a tractor trailer, the only vehicle big enough to carry it. And big piles of cash tend to attract attention, making life easier for the law.

“A lot of law enforcement agencies, particularly at the state and local level, are looking for very sophisticated laundering systems involving Swiss, Panamanian and Bahamian bank accounts,” says Karchmer. “But they really don't need to start out looking for the more complex systems. It the dealers are sitting on the cash longer, then cultivate informants and find out where the hoards are.”

While some of the money stays in the United States, at least half of it gets physically smuggled out, and that percentage may be growing. “It's becoming the method of choice,” says one Customs investigator. "It's quick, it's easy and it leaves no paper trail.” Private planes and boats, as well as unwitting courier services, are used to get the cash to any of the dozens of nearby banking secrecy havens.

“Their techniques are incredibly imaginative,” says von Raab. “A lot of it is hidden in cargo leaving the United States. We have 8 million containers entering the U.S. every year, and that means that about 8 million leave, too.” Once the cash has been deposited abroad, it can easily be wired back into the drug trafficker's account in the United States.

The preferred method is simply to load the cash onto small private jets in places like Omaha, Kansas City and Des Moines and fly it quietly to offshore havens. Once off the ground, they are hard to catch. “There may be theoretical controls, but there are no practical controls on aircraft leaving the U.S.,” admits von Raab. “When we catch an aircraft leaving the United States with cash, it's usually because a lot of hard investigating has been done.”

And the money is going out in all directions. “We estimate that there are about 450 organizations trafficking in the country, including about 50 that use Hong Kong as their laundering point,” says the FBI's Binney. “The Italians use the Swiss and Luxembourg banks, and the Colombians use Aruba, the Caymans, Panama and Uruguay.”

Each banking center has its own attractions. As the major financial center for South East Asia's drug trade, Hong Kong has long been high on the laundry busters' hit list. Its tight bank secrecy laws (criminal penalties of up to $100,000 in fines and two years' imprisonment for divulging information about accounts), favorable tax policies, lack of currency controls and wealth of money changers and international trading houses have made it a natural laundering site for the heroin-smuggling Chinese gangs who feed most of the American market.

Profits from the heroin trade “go strictly to the West Coast and out,” according to Binney, and both the smuggling and laundering rings are tough to crack. The gangs are “very close-knit, almost family-run organizations,” he says. “They only deal with people they know, and they're very difficult to penetrate with informants or undercover agents.”

Hong Kong is also home to an informal, centuries-old international banking network known as the hundi system, also known as the "chop" system. A mainstay of Southeast Asia's marijuana smuggling rings, hundi operators arrange for cash left in one city -- say, London, where 200 such operations are thought to exist -- to be delivered anywhere else in the world, in any currency desired, for a fee of 2 or 3 percent.

To claim the money, the client or his agent produces a chit (or code word, or any other prearranged signal), and the deal is done. The system is not used exclusively by Asians: Brian Peter Daniels, a Hong Kong-based trafficker arrested last summer on charges of smuggling more than 70 tons of pot into the United States, reportedly used the hundi network to pay off his Thai suppliers for years.

Traffickers bringing drugs in from the Middle East and central Asia favor European banks. And with its august reputation as a secrecy haven and international currency center, Switzerland has drawn dirty money for decades. Somewhere between 48 billion and 62 billion foreign bank notes are exchanged there every year, most of them legitimately. Launderers love having a crowd like that to blend into. But since 1972 Bern has been happy to unlock and even seize accounts if Washington can produce solid evidence that they contain drug or bribery money, and law enforcement officials express amazement that launderers still seem to flock there.

“You would think those idiots would have caught on in 1972, when we did the treaty and the Swiss started seizing money,” says Saphos. “Switzerland's the worst place in the world to put your money.”

Switzerland's bank secrecy veils are likely to rise even higher this year, in the aftermath of a laundering scandal that toppled the country's justice minister in March. It seems that two Lebanese brothers, Barkev and Jean Magharian, had come under suspicion of laundering $1.3 billion in drug proceeds through Swiss banks and currency trading houses, and that Justice Minister Elisabeth Kopp took the unwise move of alerting her husband -- who, as it happened, was the vice chairman of one of the trading houses that was about to be investigated. Her resignation followed shortly afterward.

Elisabeth KoppThe Kopp scandal focused new attention on the flow of drug money through Switzerland and set off a chorus of demands for more anti-laundering legislation. Bern is now debating tighter controls on the international bank note business, as well as making negligence on the part of bank employees a crime.

The discussion seems to be serious: For cases involving organized crime or “considerable profit,” a five-year prison sentence and fines of up to I million Swiss francs ($585,000) are being proposed. Switzerland's banks may someday be as clean as its streets.

But cleaning up the world's secrecy havens may be an Augean task. The love of money being what it is, new havens spring up with depressing regularity. Many are in the Caribbean, which traffickers like because they can use them as drug transit points to the north as well, and the right officials have already been found and bribed. (Some like the Caribbean so much they stay: The Colombian mega-dealer Carlos Enrique Lehder Rivas made Norman's Cay, one of the islands in the Bahamian chain, his home and headquarters for years.) And there is rarely any local opposition: The amount of money flowing in is “absolutely staggering," according to Morley, and that money creates jobs, raises wages and does other pleasant and welcome things.

Offshore banks are used to hide a thousand unsavory practices, from tax evasion and commodities fraud to drugs, embezzlement and corporate kickback scams. And business is booming. Setting up an effective and impenetrable laundering system using offshore banks is not only affordable (it can be done for as little as $10,000), it’s also absurdly easy. The first step is simply to set up a business in the United States to serve as a cover. It might be a restaurant, an insurance company, a car dealership -- it doesn’t really matter, as long as it has a bank account. And the trafficker can appoint himself anything from owner to employee to stockholder.

Once the front organization is in place, the trafficker then flies down to his preferred secrecy haven: say, Panama. He finds a Panamanian attorney (not difficult: they advertise widely in the international business press), who sets up an offshore finance company for him. The company (and its bank account) will be outfitted with all the proper papers, each with the attorney’s name as the president and nominee owner. The trafficker's name never appears in any of the company's public records.

“A typical lawyer will own literally hundreds of these things," says Morley. "I went into an attorney's office in the Turks and Caicos; in one of the rooms in the office suite there was a chair, a desk and several hundred corporate seals in packages, each on a piece of paper on the floor. There were literally hundreds of these things, lined up in rows on the floor so you could walk between them. And each one was a corporation."

Once equipped with a company and bank account in the haven, all the trafficker then needs to do is load up a small plane with his cash and have it flown to Panama City, where an obliging armored car will meet it at Omar Torrijos International Airport and take it directly to the company's bank. Once deposited, the cash vanishes behind the secrecy veil.

The money is now safe from North American authorities, who in most cases can only stamp their feet in frustration. The only step left is to get it back into the United States, fresh and clean. That’s easy too. The finance company makes out a loan (fully documented by the attorney) to the cover operation in the United States and wires the money northward. All the cover company has to do is make occasional interest payments - tax deductible, of course - on the loan. The deal, as far as anyone can tell, looks completely legitimate. And the trafficker has a bank account full of clean money.

This is only the simplest kind of offshore operation: Nervous traffickers can add more layers simply by shifting funds from one secret account to another. And havens are falling over one another to bring them in. A finance company can be set up in the Turks and Caicos Islands, for example, over the telephone. (The Turks and Caicos has been a friendly sort of place, trafficker-wise: Norman Saunders, the former chief minister of the small Caribbean island chain, was convicted in 1985 of drug-related bribery charges.)

The United States has been pressuring a number of the havens to open up accounts of suspected launderers and drug dealers. "It's a bit more difficult to set up a laundering operation than it used to be, because many of the havens have entered into agreements with the United States: either multilateral treaties or memoranda of understanding," says Morley. But accommodating countries will always be found. “As some havens fall, others rise," he says. "Panama is going the way of all flesh, as it were, but other places like the Cook Islands, Vanuatu, Nauru -- places in the Pacific you've never heard of -- are getting into this. They're trying to replicate what the Cayman Islands have done: build a new financial haven on a speck of land in the ocean."

Official enthusiasm in some of the havens has led, in some cases, to official corruption. In an extensive study of offshore havens conducted in 1985, the Senate's Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations found that criminal exploitation of offshore havens was flourishing, due to “government intransigence in the face of overwhelming evidence of dirty money in their banking systems."

And not just intransigence: There is, in some cases, outright collusion. In March, a federal grand jury in Boston indicted Kendal W. Nottage, a member of the Bahamian Parliament, and six others on charges that they conspired with organized crime drug dealer Salvatore Caruana to hide $5 million in drug profits and defraud the IRS. Nottage was a former Cabinet member of Prime Minister Lynden Pindling, who came under suspicion in 1983 when two of his high-level officials were arrested in a bribery sting operation connected with drug trafficking. There were charges at the time that Pindling himself was associated with fugitive financier Robert L. Vesco; the charges were dropped, although Pindling's bank accounts showed deposits of $3.5 million more than his salary between 1977 and 1983.

But compared with the kind of official corruption going on in Panama, the Bahamian officials look like choirboys. Blessed with a strategic location, tight bank secrecy laws and all the other legal rigmarole for hiding dirty money, Panama has been a magnet for money launderers for decades. Hundreds of international banks have branches there, and uncounted thousands of registered companies flourish. Panamanians like it that way; a 1985 congressional study found that the country's financial institutions employed 8,000 people, all of them prospering from the country's secrecy laws. Like Hong Kong, it is a place where money talks and everybody speaks the language.

Manuel NoriegaUnlike Hong Kong, Panama is also a place where cooperation among the government, banks and the drug underworld is, for all intents and purposes, institutionalized. “Panama is just a prostitute when it comes to its banking system,” says von Raab in disgust. The biggest of them all is the country's leader, Noriega, who was indicted in the United States in February last year for using his official position to protect hundreds of traffickers and launderers, including members of the Medellin cartel.

The indictment claimed Noriega had taken more than $4.6 million in payoffs to provide airport facilities and protection; one launderer, Steven Kalish, told a congressional committee that he had bribed Noriega and his associates for help in laundering some $100 million. Noriega has rejected the indictments, claiming repeatedly that Washington was stirring up false charges in order to have an excuse for hanging on to the Panama Canal, which is scheduled to revert to ownership by Panama in 2000.

The indictment of Noriega frightened launderers, who began to shift their money elsewhere. But “now that Noriega is better settled, I think that a little more confidence is returning to the Panamanian system,” says von Raab. That, he implies, is due to Washington's overly delicate handling of the Panamanian. “There was one point when they were really scared that there was a lot of money in the U.S. that wasn't moving to Panama. But Noriega gave the finger to the U.S. a couple more times, we flinched and the money came back.”

The presence of people like Noriega makes federal investigations difficult and sometimes impossible. The big laundering busts of this decade have been immensely complicated, time-consuming and expensive. Two or three years can be spent infiltrating a laundering operation and gaining the target's trust. That has meant that the feds have had to focus on only the biggest groups, letting the smaller fish get away.

“In these kind of investigations you're talking about six or seven subpoenas and trying to get something from the Marshall Islands, and so on,” says the DEA’s Omdorff. “It's eight or 10 months of work to find out what happened.”

But law enforcement techniques have been advancing, and growing emphasis is being put on electronic surveillance rather than infiltration. And while each of the various federal agencies conducts its own independent investigation, more are being conducted on a joint basis without any one agency necessarily taking the lead.

“A lot of these guys will be involved in money laundering, fraud, arms, illegal aliens and cocaine smuggling,” explains Omdorff. “So DEA does the drugs, IRS does the money, INS looks at the aliens, and so on. We pool funds and work as a group.”

The more expertise that can be brought to bear, the better. The laundering operations of the next decade will be extraordinarily intricate and imaginative, and the drug agencies have been scrambling to keep one step ahead. That has meant changes in the way some of them approach the drug problem and train their agents.

“While the traffickers learn, so do we,” Omdorff says. "We're constantly evaluating our approach. And modem-day narcotics agents aren't what they used to be; now you're not just worried about going undercover and buying a gram of coke. You understand treaties, banking laws, financial information.”

The big busts of the past few years have made the traffickers more wary of whom they hire. “They're getting leery,” says Omdorff. “When you go undercover as a money launderer they ask you 10 zillion questions, and when they try you out they do it with $10,000 rather than $50,000.” Some are even fighting back with extensive background checks on prospective launderers. “They've started contracting with private investigation firms,” says another federal official. “We had a case in San Francisco where a dealer's investigator reported back that he thought he was dealing with drug enforcement people. It caused a lot of problems.”

But the growing complexity of the laundering operations and the entry of new people into the field has, in some ways, made it easier to bust them.

“The good thing about money laundering is that it's not a one-person operation,” says the IRS's Bruh. “And the more people they need to help them, the more vulnerable they are to us. Frequently we'll grab people for other reasons and turn them, and as part of their cooperation with us they'll tell us about things we didn't even know were going on.” The huge La Mina operation, in fact, came to light only after agents posing as launderers were told by a cartel operative that they were too slow in processing the funds. “You should learn from La Mina,” they were told. “They can launder the money in 48 hours.”

And with the prospect of becoming a millionaire overnight, new blood is streaming into the drug business all the time, while established traffickers work on expanding their operations.

“They're developing new networks, and they need new people all the time to help them move their money,” says Bruh. “They're greedy.”

For all the recent successes, U.S. agencies say they can do only so much without international cooperation. "The most important development of the past year has been the involvement of other countries in money laundering investigations," says von Raab. “This isn't a local problem; it's global.” The United States has been drawing up mutual legal assistance treaties with a number of other key countries, and most now will cooperate in drug cases. Many, however, refuse to hand over information in tax investigations.

“It's more difficult for us than for other agencies, because some other countries like the idea of being havens,” says Bruh. “Sometimes they'll give information to U.S. federal agencies with the proviso that we don't get it.”

Cooperation is gradually becoming institutionalized. Declaring that the world drug problem has reached "devastating proportions," a summit meeting of the so-called Group of Seven industrialized nations in mid-July called for an international task force on money laundering to be set up. The Financial Action Task Force, as it has been christened, will meet later this year in France and will produce a report on the problem by April. In Washington, officials seem pleased, if slightly impatient, with the progress. “At the last summit in Toronto, there was just a line on money laundering,” says Treasury's Martoche. “This time, there was a couple of pages.”

Perhaps more significantly, a December U.N. conference in Vienna adopted a Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs. Once adopted by a majority of U.N. members, it will require them to make drug-related money laundering illegal, allow authorities to confiscate drug proceeds, seize bank and commercial records and foster mutual legal assistance. The convention also would allow nations to share confiscated property and put the proceeds back into fighting drugs.

More than 70 people were indicted in the wake of the C-Chase stingThe importance of international cooperation was proved last October, when a two-year sting operation called C-Chase ended in the indictment of more than 70 people and, for the first time, an international financial institution: the Luxembourg-based Bank of Credit and Commerce International.

The ring (whose leader, Roberto Baez Alcaino, pleaded guilty July 6) was a major operation supplying clean money to the Medellin cartel and dozens of other traffickers. The sting's success was due to “the direct and significant involvement of French and British officials,” says von Raab. “To my knowledge, it was the first really identifiable case of international co-operation.”

Outside the United States, legislation governing money laundering is still skimpy. But that may be changing under pressure from Washington. In the so-called Kerry amendment to the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988, the Treasury Department was directed to reach agreements with foreign banks to ensure that cash transactions of $10,000 or more are recorded wherever in the world they take place and that the records be made available to U.S. investigators. If, by November 1990, a country is found to have negotiated "in bad faith," the president can terminate all banking relationships with that country's financial institutions. That's a powerful threat; it would effectively put a choke hold on a country's trading relationship with the United States.

Predictably, several countries, including Canada, have protested. But the Kerry negotiations are going well, says Treasury's Martoche. “More and more people are seeing money laundering not as an American problem but as a global problem.”

That is especially true in Europe. Only France and Britain have legislation against money laundering, but as Latin American dealers move into the European market, interest and cooperation there have been spreading. Most observers say that the full force of the cocaine trade has yet to be felt across the Atlantic but that market conditions make it inevitable that Europe will be hit, and hit hard. “Six months ago, we had a guy negotiating for $47,000 a kilo in Toronto, while it was going for between $18,000 and $20,000 in New York,” says Omdorff. “In Europe, it's about $60,000 it kilo.”

The prospect of a burgeoning cocaine market in Europe has money launderers there salivating in anticipation, and American officials fear that plans to remove all controls on currency movements within the 12-nation European Community by the end of 1992 will only make matters worse.

“I'm worried about it because the Colombian cartels are excited,” says von Raab. “When those barriers drop, it's going to be the weakest-link problem. All the good money laundering laws in the world in Great Britain and France aren't going to help; they can park all their money in Germany, which is particularly obsessed with not touching the banks."

It is not just the Latin traffickers who are looking forward to 1992. Carlo Azeglio Ciampi, governor of the Bank of Italy, told the Italian Parliament's Anti-Mafia Commission earlier this summer that the Mafia intended to launder and invest billions in the European Community. With an estimated $75 billion in annual income (much of it from heroin, and its interest in cocaine growing), the Mafia's penetration into the Italian financial sector is already said to be enormous; one investigator has warned of a "tight alliance between money of illegal provenance and financial sectors."

Barring extreme measures, it seems unlikely that the Mafia's grip on some of the country's financial institutions can be pried off by 1992. The Italian Banking Association has asked its members to check the identities of anyone depositing or withdrawing more than 10 million lire (about $7,300), but without any strong legislation to back up the new requirements, they are unlikely to have much real effect. The U.S. Justice Department has developed a cooperative effort with the Guardia di Finanza, the investigative wing of the Italian treasury, to exchange data. But the plan, called Primo Passo, is just as its name suggests: only a first step.

With the predictions of a drug explosion in Europe, and a potential explosion of heroin use in the United States, no one involved in the war on drugs thinks it will ever be possible to wipe out money laundering. Whenever one operation is busted, another will come up to take its place. But the fight against the drug lords continues. “Five ‘Polar Caps’ are not going to end this problem,” says Bruh. “But at least it keeps it to a certain level of control. And if there's nothing else we're doing, at least we're seeing to it that these particular people are out of business.”