Pink Martini Shakes It Up

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • September 23, 2006

_______________________________________________________________________________

Does America need a Pink Martini?

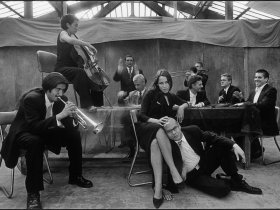

Yes, please -- and right away, to judge from the wildly enthusiastic crowd at George Washington University's Lisner Auditorium on Thursday night. This 12-piece band from Oregon has been a major hit in Europe with its genre-busting mix of styles ranging from Brazilian sambas and Japanese film music to torch songs from the 1930s. Its two self-produced albums have sold more than a million copies around the world.

And at the sold-out Lisner show, where the band ended a rare North American tour, Pink Martini showed why it may be turning into the next big thing here, too. Opening with a smoldering, lounge-music version of Maurice Ravel's "Bolero," the band launched into a wild, two-hour ride through several decades and a dozen languages and styles -- a sort of "urban musical travelogue," as pianist Thomas Lauderdale puts it -- that was pure electricity from beginning to end.

Opening with a smoldering, lounge-music version of Maurice Ravel's "Bolero," the band launched into a wild, two-hour ride through several decades and a dozen languages and styles -- a sort of "urban musical travelogue," as pianist Thomas Lauderdale puts it -- that was pure electricity from beginning to end.

Lauderdale and singer China Forbes call themselves "musical archaeologists," digging up neglected treasures and styles from the past and reinventing them for the 21st century. But there's nothing pedantic about the result: This is rich, hugely approachable music, utterly cosmopolitan yet utterly unpretentious. And it seems to speak to just about everybody: The Lisner audience included everyone from grade-schoolers to grandmothers to the young and hip and beautiful.

Forbes delivered elegant accounts of more than a dozen of the band's favorites, including "Let's Never Stop Falling in Love" (which, like much of Pink Martini's music, she co-wrote with Lauderdale) and the swooning, heartfelt "Amado Mio," as well as new pieces like the 1934 song "Tempo Perdido," from the band's upcoming album -- tentatively scheduled for release in February.

Forbes has a fine, velvety voice, and though she may not yet have the richness and dramatic power of a great cabaret singer, she made up for it Thursday with style, sliding from sultry ballads into whispery Japanese melodies without a trace of effort. Throughout, she radiated a kind of femme-fatale-in-training charm -- the girl next door who's not quite sure how she ended up onstage but is going to make like a vamp anyway.

For all the sophistication of the music, there was an agreeably homespun atmosphere to Pink Martini's stage show. Pianist Lauderdale (as chic as could be in a short-sleeve shirt, bow tie and platinum-dyed hair) played with his back to the audience and only rarely displayed his virtuosity, giving the spotlight to the other band members -- with spectacular results. Cellist Pansy Chang's solo in the dark Croatian song "U Plavu Zoru" was pure dark honey, moody and evocative, while Gavin Bondy on trumpet, Robert Taylor on trombone and Dan Faehnle on guitar kept things storming through hard-driving tunes like "¿Donde Estas, Yolanda?" and "Una Notte a Napoli."

By James Wilderhancock

Lauderdale and Forbes believe the diversity of the band's members is at the heart of Pink Martini's musical eclecticism.

"It's really a result of the number of people in the band, who all come from different backgrounds, from classical to jazz to Brazilian to Cuban," Forbes said in a phone conversation from Cleveland last week, where the band was performing at the Museum of Art.

Both she and Lauderdale grew up in multicultural families -- she's partly African American, while Lauderdale (who calls himself a "mystery Asian") is one of four racially diverse adopted children.

"I grew up playing classical, and China's more folk-rock-pop," Lauderdale said. "And because everybody in the band has a voice and everybody writes music, it translates to quite a diverse repertoire."

Pink Martini got its start in 1994, when Lauderdale put a band together in Portland, Ore., to play at fundraisers for progressive causes. He invited Forbes to join him (the two had become friends while undergraduates at Harvard), and they began writing songs and released their first album, "Sympathique," in 1997. They weren't expecting much to happen ("we released it in a sort of 'Portland' way," said Forbes, laughing), but the lilting title song was picked up by Citroen for a commercial and became a huge hit in France -- launching the band's European career.

The extensive travel put them in the role of cultural diplomats, Lauderdale said.

2004's "Hang On Little Tomato""American pop culture sends a very particular image of what American culture is," he said. "I think the band represents a larger, more diverse America, so it's more authentic in that way."

Pink Martini's real mission, he said, is to deepen American pop music by exploring the past.

"One of the sad things about modern American culture is that there's not much awareness of history on the part of the younger generation," he said. "There's sort of a cultural and social and historical amnesia."

Lauderdale thinks that, in music, he's found an essential ingredient for surviving the 21st century.

"There's such optimism in the music from the past!" he said. "And if we're writing music in that style, the challenge is to find that true optimism -- despite everything that we've learned and everything that we know."

Composer Mark Adamo, Wild at Harp

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • June 3, 2007

_____________________________________________________________________________

Mark Adamo is the fastest-rising new opera composer in the country, with back-to-back hits, a national PBS broadcast and major companies lining up to perform his work. So why is he back in Washington this week, not to wow the opera world but to premiere a decidedly non-operatic concerto for . . . the harp? "Most writing for the harp is so trite!" says the composer, echoing a sentiment widely (if quietly) shared among music lovers. "We always hear this perfumed, elegant persona for the harp. It's Sunday morning brunch -- eggs Benedict with the harp strumming in the background. And the only thing more trite than that is all those insipid Christmas-card angels with which the harp is constantly associated.

"Most writing for the harp is so trite!" says the composer, echoing a sentiment widely (if quietly) shared among music lovers. "We always hear this perfumed, elegant persona for the harp. It's Sunday morning brunch -- eggs Benedict with the harp strumming in the background. And the only thing more trite than that is all those insipid Christmas-card angels with which the harp is constantly associated.

"So I decided," he says with a laugh from his studio in Upstate New York, "to kill two cliches with one stone."

And when it premieres on Thursday, "Four Angels" may set the harp world on its delicate ear. Five years in the making, it's an unbridled ride through the empyrean, portraying angels from Christianity, Islam, Judaism and Zoroastrianism not as simpering cherubim but as wild, passionate creatures. Released from its genteel prettiness -- and armed with unusual techniques such as pedal crashes and key glissandos -- the harp soars across a heaven-scape both terrifying and sublime, wreaking havoc and transcendence as it goes.

"It's like nothing that's ever been heard on the harp before; it's going to change the way people think," says Dotian Levalier, the National Symphony's principal harpist, who commissioned the work. "When we first talked about this, I told Mark that I didn't want another delicate, tinkly piece -- I wanted something with some meat behind it. And I think I got it."

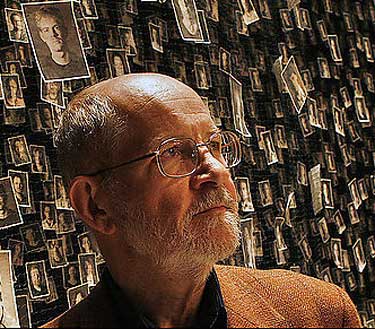

Photo by Martin GramFor Adamo, 45, the Kennedy Center premiere is a sort of debut -- it's his first concerto and his first major purely orchestral work. But it's also a homecoming. Adamo's career began in Washington when, as a composition student at Catholic University in the late 1980s, he struggled to make the rent and get his music heard.

Fortunately, he found a few angels of his own -- National Symphony Orchestra players Levalier, bassoonist Linda Harwell and Sylvia Alimena, a horn player who was then launching her now-acclaimed Eclipse Chamber Orchestra.

"I first met him when he was a waiter at the West End Cafe," says Alimena, referring to a restaurant just a few blocks from the Kennedy Center. "A bunch of us used to go there after National Symphony concerts, and we got to know him. At some point he asked us if we wouldn't mind playing one of his pieces, and I noticed how beautifully the wind parts and string parts were written. And I thought, this kid's kind of talented!"

Alimena was so impressed that she urged Adamo in the early 1990s to write a piece for her new orchestra. It was an offer that any young composer would have jumped at, but Adamo did not take it seriously at first. His real interest was musical theater, and despite being active in the local music scene -- singing in the Congressional Chorus, directing productions of light opera, and even writing music criticism for The Washington Post -- the idea of being a composer seemed almost absurd.

"I really only wanted to become overqualified as a theater songwriter -- that's why I was studying composition," he says. "Like a lot of people, I thought that unless you're Benjamin Britten and you've written five piano sonatas by the time you're 10, you're not going to be a composer."

But Alimena persisted, a deadline was set, and Adamo went to work. "I was having that year that people have, when all your friends start dying," he recalls. "I had an idea for an AIDS piece -- but to do a piece on that subject, of course, was heavy going. So I told Sylvia, 'I understand if it's not right for you.' And, God love her, she said, 'Just write what's in your heart.' "

The advice worked. "Late Victorians" -- an AIDS memorial for singer, speaker and orchestra -- premiered in 1995 to immediate critical and popular acclaim, and led to a commission from the Houston Grand Opera for a full-blown opera. Fully over his reluctance to consider himself a composer, Adamo wrote the lyrical, two-act "Little Women" (based on Louisa May Alcott's classic coming-of-age novel) and when it premiered in 1998, he joined the front ranks of American opera composers almost overnight.

The New York Times declared the opera a "masterpiece" and audiences responded to its humor, warm lyricism and fast, engaging flow. (Adamo, originally trained in theater, wrote the libretto himself.) In less than a decade, "Little Women" has been produced more than 40 times around the world, and in a rare coup for a maiden opera, was broadcast nationally in 2001 as part of the PBS "Great Performances" series.

With his career now officially meteoric, Adamo followed up with more successes -- notably the wildly funny 2005 opera "Lysistrata, or the Nude Goddess" (also written for the Houston Grand Opera). He became composer-in-residence for the New York City Opera (a post he held from 2001 to 2006), further refining a sophisticated, wide-ranging musical style that embraces everything from 12-tone modernism to Broadway show tunes, and even -- in the case of "Four Angels" -- the exotic sonorities of Chinese gongs.

That kind of eclecticism hasn't always impressed critics; Alex Ross, the classical music critic for the New Yorker, once praised his "dexterous synthesis of 20th-century techniques" while wondering if that's what the world really needs. But Adamo says that being flexible and using the vast global musical palette is the right -- maybe even the obligation -- of every contemporary composer.

"Why shouldn't I use the sound of Chinese gongs in a harp concerto?" he asks, railing against "the purity police" who demand that music fit into rigid categories.

"The history of concert music is one of almost unremitting ethnic war -- the French against the Italians, against the Germans, against . . ." He heaves a weary sigh in the direction of Europe. "But now, every nation is represented everywhere. We live in the world, rather than in one particular culture. For good or ill, it's a global village. And our challenge, artistically, is to make sense of all this incredible variety."

Adamo's now preparing a new opera for the San Francisco Opera; he won't disclose its subject yet, but says it will be "bigger and less fleet" than his previous works. He's also working on a collaboration with his partner of 12 years, composer John Corigliano, and is revising and recording many of his early works, several of which will be released on a Naxos recording next year by the Eclipse Chamber Orchestra.

As far as his angels are concerned, Adamo's rise has only just begun.

"My colleagues and I feel very strongly about Mark's music," says Alimena. "He's extremely brilliant, hysterically funny and rarely earthbound. But the important thing is that he's not afraid to sing. So many composers rely on percussion and loud noises. But Mark's not afraid to be lyrical, to show a tenderness in his writing. And I think that's why his music touches people so deeply -- and on so many levels."

The National Symphony Orchestra under Leonard Slatkin will perform Mark Adamo's Four Angels on June 7-9 at the Kennedy Center. The program also includes symphonies by Haydn and Mahler.

Mason Bates: Bringing Electronica to the Concert Hall

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • February 21, 2007

_______________________________________________________________________

Tomorrow night at the Kennedy Center, Al Gore's worst nightmare will come to pass. Massive glaciers will calve from the ice caps and crash into the sea. Temperatures will rise, boiling the oceans into a fury as the planet gets hotter and hotter -- until finally a massive flood inundates the continents.

Tomorrow night at the Kennedy Center, Al Gore's worst nightmare will come to pass. Massive glaciers will calve from the ice caps and crash into the sea. Temperatures will rise, boiling the oceans into a fury as the planet gets hotter and hotter -- until finally a massive flood inundates the continents.

That's the apocalyptic plan, anyway, for the premiere of "Liquid Interface," a new work by the young California composer Mason Bates. Commissioned by the National Symphony Orchestra, the piece may be the first attempt to deal musically with the drama of global warming. But that's not the only new thing about this work. Throughout the performance the composer himself will be sitting at the heart of the orchestra, working a laptop and generating huge waves of electronica -- pulsing trip-hop rhythms straight from the dance clubs of the Left Coast.

Wait -- the NSO playing . . . techno?

"There's plenty of rhythmic activity in the piece, and a lot of trip-hop beats," confirms Bates. "But I don't think you'll see people doing head-spins in the aisles."

At age 30, Bates is already rocking the classical world. One of the fastest-rising young composers in the country, he's written a string of serious works for serious orchestras -- including the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Winston-Salem Symphony and now the NSO -- and won an array of prestigious awards, from the Rome Prize to a fellowship from Tanglewood. Born and reared in Richmond, he trained at Juilliard and is now finishing up a doctorate at the University of California at Berkeley.

By night, Bates heads for the clubs of San Francisco, where as DJ Masonic he churns out driving, sophisticated dance music at places like Skylark and Cloud 9. Armed with a computer and electronic drum pad, he plays into the small hours of the morning, weaving complex, highly rhythmic sonic landscapes.

It would seem to be as far from the concert hall as you could get. But over the last few years, Bates has been bridging the two worlds with a natural ease, writing music that marries the intellectual seriousness of classical with the visceral kick of techno. "He's one of the few people who can mix electronica and pop with abstract music, and do it well," says Pulitzer Prize-winning composer John Corigliano. Other composers have tried, he says, usually just dishing up a porridge of "bad classical music and bad pop music at the same time." But Bates's pieces, he says, "are like little jewels -- he inhabits this fantastic sound world."

"He's one of the few people who can mix electronica and pop with abstract music, and do it well," says Pulitzer Prize-winning composer John Corigliano. Other composers have tried, he says, usually just dishing up a porridge of "bad classical music and bad pop music at the same time." But Bates's pieces, he says, "are like little jewels -- he inhabits this fantastic sound world."

Orchestral music and techno are more alike than they seem: They're both instrumental, both are designed for open, cavernous spaces and both have a near-infinite potential for texture and color. Put them together, Bates says, and a world of "very pregnant possibilities" opens up:

"There's a lot of cross-pollination. Orchestral writing changes what you do in electronica, and when you spend any time in an electronic studio, you definitely think about E-flat on the oboe in a new way. And the long spans of time in electronica -- where textures shift very slowly -- change your perspective. My approach to musical architecture has become far more stretched out."

But electronica's most important contribution, says Bates, may be a propulsive, physical energy that's been conspicuously absent from much of the rigidly codified "serious" music of the past 50 years.

"I need to be moved viscerally by a piece of music," he says. "Music's not like any other art form -- you can't escape the physical quality of it. It inhabits your imagination and your bloodstream at the same time. Ultimately I want a piece to pay intellectual dividends -- but I have to be captivated by it first."

In a sense, Bates's mash-up of techno with the orchestra is bringing things full circle. Electronica's roots go back to composers such as Edgard Varese (whose 1958 "Poeme Electronique" may have launched the genre) and Pierre Schaeffer, who used sound samples in the 1950s in a style called "musique concrete." And a few composers of the late 20th century -- the pathbreaking Iannis Xenakis, in particular -- are routinely cited by electronica artists as major influences.

But electronic sounds never caught on in classical music the way they did in pop, where they've blossomed in everything from Top 40 to favela funk. And, since emerging in the 1990s as a style in its own right, electronica has spawned an array of genres and subgenres: acid house, drum 'n' bass, electroclash, booty bass, etc. Bates seems uniquely positioned to bring all of this into classical music. "What Mason does is, in a way, a throwback to the 1960s, when composers were first starting to use electronics with the orchestra," says NSO Music Director Leonard Slatkin. "But very rarely were the electronics integrated into the music; they always stuck out as just an added thought. With Mason, they're an integral part of the work."

Bates seems uniquely positioned to bring all of this into classical music. "What Mason does is, in a way, a throwback to the 1960s, when composers were first starting to use electronics with the orchestra," says NSO Music Director Leonard Slatkin. "But very rarely were the electronics integrated into the music; they always stuck out as just an added thought. With Mason, they're an integral part of the work."

Bates first bridged the classical-electronica gulf in a 2004 commission for the Los Angeles Philharmonic, "Omnivorous Furniture." Written for sinfonietta and electronica, the work's success quickly led to more commissions, including a piece for Juilliard's 100th anniversary called "Digital Loom" (for organ and electronica). Word of Bates's talent reached Slatkin, who contacted the composer two years ago to write a 20-minute work.

It was propitious timing; Bates already had an idea for a major piece. "I was living in Berlin, near a huge lake there called the Wannsee," he recalls. "I had been watching it go through extremes, from totally frozen to hot and humid in a matter of weeks. So I thought it would be fascinating to do a new kind of water piece -- not just Debussy's play of the waves, but a piece on water in all its forms, moving from ice to evaporation.

"And I wanted to look at it through the prism of the 21st century. So the whole piece is structured around things gradually heating up."

When the work premieres tomorrow (in a program that includes the more traditional fare of Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto in E Minor and Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 6), it will open with a roar -- actual recordings of glaciers calving in the Antarctic -- while the orchestra picks up the imagery, building huge blocks of sound that shift, drift and start to break apart as the temperature rises. As that's happening, says Bates, "the electronics enter with these very fat beats and slow-motion trip-hop beats," based on samples of actual water sounds. Propelled by the beat, the orchestra creates a swirling world of sound, bringing the work to an apocalyptic (or even biblical) flood. But then the waters recede, calm returns, and a simple melody floats over peaceful sounds recorded at the side of the Wannsee, until the final notes simply evaporate away.

"You end up," says Bates, "in a sort of greenhouse paradise, where it's very balmy."

Hold on -- global warming has a happy ending?

"Well, I'm leery of preaching," he says, noting that it was the dramatic aspects of global warming, rather than the politics, that intrigued him. "Absolutely, composers should address the big issues of the day, but I'm not sure a composer is going to have the answers. What's important is to pose the questions."

© 2007 The Washington Post Company

Photos: Max Lautenschlager; Christina Schroth

In Trinidad, Beating the Steel Drums of War

By Stephen Brookes

in Port-of-Spain for Insight Magazine

It was shaping up to be a very tough fight. The Witco Desperadoes' version of Tchaikovsky's "Marche Slave" was powerful, and they’d won Trinidad and Tobago's last national steel band competition.

But their rivals, the Solo Harmonites, were weighing in with a smooth, elegant reading of Wagner's "Rienzi" overture. And a feisty dark horse called the Tropical Angel Harps had wowed the judges in the semifinals with a shimmering performance of Rimsky-Korsakov's "Scheherazade.” At the battle that night in the national stadium, the bands would be coming out with all drums blazing.

Stephen BrookesIn the end, though, after a grueling 10-hour competition that ended in the small hours of the morning, the 60-man Desperadoes won the fifth Pan Is Beautiful Festival in Port-of-Spain -- winning glory, a North American tour and a chance to perform at Carnegie Hall.

But they also became the representatives of what this Caribbean island nation increasingly sees as its most important contribution to world culture: music.

Steel band music -- or “pan” music, as it’s properly known -- is not taken lightly in Trinidad. Every Trinidadian has his favorite band, whose ups and downs are followed passionately by everyone from Cabinet ministers to the peanut sellers in the side streets of Port-of-Spain.

The instruments themselves, which are made from old oil drums and are capable of an astounding range of pitches and sonorities, have become increasingly sophisticated, and playing them has developed into a fine art. Popular pannists enjoy the status of rock stars, the tabloid headlines scream rumors about their romances, and at Carnival time the excitement turns into fever as thousands of fans take to the streets to dance all night to the pan.

But the pan is also starting, slowly, to gain recognition in the rest of the world as a serious instrument, one that can hold its own in almost any musical setting and can legitimately be used to interpret even the Western classical repertoire.

"The stereotype of pan music is happy black man with nice white teeth, straw hat and banana shirt playing 'Yellow Bird' and 'Island in the Sun,'” says Richard Murphy, one of the festival's judges. "That's 30 years out of date."

Easley Blackwood. a music professor at the University of Chicago who has been a judge at the festival since 1984, agrees, complaining that his colleagues in the U.S. music world do not take pan seriously enough.

"They do not realize that it really is high-class music making, very accurately and beautifully played, and getting more sophisticated all the time,” he says.

Pannists trace the steel band's roots to the late 19th century, when informal bands would make music by banging different lengths of bamboo -- known as tambo-bambos -- on the ground to produce percussive tones. Despite suppression by the British colonial government, which worried about the music's political overtones, tambo-bambo bands flourished well into the 1930s.

But it wasn’t until U.S. naval forces pulled out of Trinidad in 1945, leaving behind thousands of empty oil drums, that the pan itself was invented.

Despite a great surge of popularity throughout the country, the instrument continued to enjoy official disfavor as being noisy and disreputable. associated with troublemakers and anti-colonial rabble-rousers. An anti-pan law was passed in 1949, giving the police the freedom to smash the drums and arrest anyone caught playing them. But the easy availability of the drums made it impossible to wipe them out.

www.seetobago.com"The pan was created by the society's rejects," says Arnim Smith, president of Pan Trinbago, the group that represents the country's steel bands. "And it was a struggle against the police, against the judges, against everybody. But the determination was there. We created something, and we just could not let it go."

Smith believes that the official suppression bred further violence among the bands through most of the 1950s. Fist fights would break out when gangs of pannists, wearing the drums around their necks, met each other in the streets. To contain and channel the violence, the first steel band competition was set up in 1962, and the festivals are now held every two years. The players welcome them.

"If it weren't for these competitions, a lot of the bands would hardly be heard," says Fitzroy Innes, leader of the Tropical Angel Harps.

The festivals have also pushed pan music well into the mainstream. There are more than 130 pan orchestras in Trinidad and Tobago, with as many as 50,000 players around the country. Steel bands play everywhere from churches to clubs to the Port-of-Spain Hilton, and the players come from all walks of life.

"The band is a wide cross section of the society,” says Innes. "We have professional people, government employees, teachers, students. trades people.”

Steel bands come in various configurations, but a full-size orchestra will involve 30 to 100 pannists, each playing up to nine different drums. The highest-pitched pans (known as the front-line pans) are the tenors and double tenors, which carry the melody. They’re backed up by increasingly larger and deeper pans - the double seconds, the treble guitars and the cellos - which fill out the harmonies.

A relatively new pan called the quadraphonic provides a deeper voice, while the lowest pans, known as the tenor bass and the six bass, are full-size drums that carry the bass line. The band is finished off with a standard percussionist, sometimes reinforced with gongs, tambourines and other instruments.

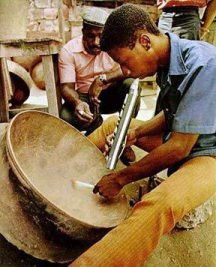

Despite improvements and refinements over the years, most pans are still made as they were in the 1940s, by cutting down standard 42-gallon oil drums and hammering small, resonant domes into the surface, creating up to two dozen separate pitches.

But pan makers are no mere bangers. Every oil drum is considered distinct: Different alloys result in different sonorities, and a maker will carefully test a particular drum before it is earmarked as a high- or low-pitched pan.

Jaime OstercampTesting the sound of the drum surface with a small hammer, the pan maker will fit the placement of the notes to each particular drum. The surface of the drum is then "sunk" with a sledgehammer, and the individual notes "hammered up" from below into shallow domes - a process known as "ponging up" the pan. After tempering in an open fire and a final tuning, the pan is ready for play.

The result is a handmade instrument with an individual sound; an orchestra will have a well-blended sound only if the pans are made and tuned by the same tuner. That, plus the different tuning systems used, has created problems: Two orchestras that had planned to come to this year's festival from Sweden and Britain, for example, had to pull out due to the high cost of transporting their instruments. Standardizing the instruments and their tuning remains a controversial matter.

Playing classical music on the pan has been necessary to secure its stature as a modem musical instrument, pannists say, but it also has shown just how broad and colorful the steel band's musical palette really is. From delicate, shimmering passages that suggest the ethereal sound of a glass harmonica, to detailed counterpoint, intricate passagework and thundering, unstoppable percussive crescendos, the sound of a full-size steel orchestra is, in a word, extraordinary. It has an uncanny ability to evoke the sound of trumpets, woodwinds, even strings. Ringing with complex harmonics, the sound is almost hypnotic.

Says Jerry Jemmott, who has led the Solo Harmonites on tours around the world, “Audiences who hear pan orchestras in Europe can't believe we're getting all these different tones from it. They come up and look around for wires: They think we're using a synthesizer."

Given the unique sound of the steel pan, however, the choice of music is critical. Although works as complex as Stravinsky's "The Rite of Spring" have been played in the past, most choices come from the classical and romantic eras. "Atonal, dissonant music is not successful on pan," says Blackwood. "It just degenerates into confusion. What they are best at - aside, of course, from the calypso - is the big, splashy 19th-century pieces that modulate all over the map "

And the bands have been ambitious. Among this year's pieces were selections from "The Planets" by Gustav Holst, "La Forza del Destino" by Guiseppe Verdi, selections from Richard Wagner's "Me Flying Dutchman" and works by Mozart, Rossini and Aaron Copland.

The music is played entirely from memory. Often only one or two members of the steel band will be able to read music; they’ll play the notes directly off a miniature score, assigning parts on the basis of range, and each player will memorize his part. The whole process takes about six months to bring a piece to readiness.

"We have a core of about 20 really sharp guys," says Clarrie Benn, an official with Trinidad's Central Bank who also manages the Tropical Angel Harps.

"They'll work the tune over and then teach it to the slower ones. That way we can move much faster, instead of starting from scratch with the full orchestra."

While the classical repertoire lends the bands legitimacy, the groups really seem to come alive when they play the traditional Caribbean calypso. New tunes are generated every year for Carnival, and the most popular are soon arranged for pan orchestra. With their lilting melodies, their mix of African, Indian and Spanish cultures and their irresistible rhythms, calypsos are uniquely West Indian.

"The calypso gives you freedom," says one player. "There’s a driving force in it," agrees the Harmonites' Jemmott. "You couldn't stand at attention and play this music. You just got to bounce!"

Acceptance is still an uphill battle. But as more bands tour and record, and audiences become familiar with the music, promoters expect that the steel band's appeal will grow. Such well-known pop and jazz stars as Paul Simon, Aretha Franklin and Monty Alexander have used pans in recent recordings, and steel band promoters confidently predict that this is just the beginning.

"We're going to diversify the music," says Simeon Sandiford, who has recorded most of Trinidad and Tobago's steel bands. "The culture is so rich. We're working with jazz musicians, with Indian musicians, everything." Sandiford recently released the first steel band compact disc earlier this year on the Delos label and thinks the future is bright.

"We're ready to take on the world," he says. "No doubt about it."

(Insight Magazine, December 8, 1988)

Taking a Chance on Sophie's Choice

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • September 20, 2006

___________________________________________________________________________________

Sophie's Choice, William Styron's searing 1979 novel, is nothing if not operatic. The tale of Auschwitz survivor Sophie Zawistowska's attempt to build a new life in America is almost unbearably tragic, careening through a nightmare of passion, madness, cruelty and death, until it reveals the devastating act of brutality at its core.

Operatic, definitely. But is it opera? Or, more precisely, is the sprawling, troubled opera that British composer Nicholas Maw unleashed on the world four years ago finally ready for prime time?

Nicholas Maw By Nikki Kahn - The Washington PostThe Washington National Opera, which is giving Maw's "Sophie's Choice" its American premiere tomorrow, is betting it is.

But it's a big bet. The opera received a lavish -- and lavishly hyped -- premiere in London's Covent Garden in 2002, when it had five sold-out performances and was praised by conductor Sir Simon Rattle as "an instant classic." But it was widely and savagely beaten by critics who (though they praised the music and swooned over the singing) found the opera itself a sodden mess.

"Too long, too wordy and . . . too discursive to establish a dramatic pulse," sniffed the Financial Times. "It rambles on at a leisurely pace and gets nowhere," echoed the Daily Telegraph, complaining that "it has no edges, no ambiguities, no crackle of tension." The London Times voiced a note of hope when it said that "cocooned inside . . . [this] four-hour opera is a two-hour masterpiece struggling to get out." But the Guardian hammered in a final nail. "As it stands," the paper wrote, "the opera is unworthy of revival."

It might have expired then and there, but the work's charms proved irresistible. After all, the music was gorgeous -- virtually everyone agreed on that -- and Styron's tale of the beautiful, broken Sophie, her volatile lover Nathan Landau and the naive young writer they befriend already had an impressive track record. The novel shot to the top of the bestseller lists, won the 1980 National Book Award, became an Oscar-winning film starring Meryl Streep and is routinely ranked as one of the top 50 American novels of the 20th century.

How could the opera fail?

So after a respectful pause of several moments, the Washington National Opera jumped in. Partnering with Vienna's Volksoper Wien and Deutsche Oper Berlin, they put together an all-star resuscitation team. The four original leads -- super-mezzo Angelika Kirchschlager as Sophie, Rod Gilfry as Nathan, Gordon Gietz as Stingo and Dale Duesing as the Narrator -- were retained for the U.S. premiere. The Baltimore Symphony's Marin Alsop, who has a reputation as a tough, brainy conductor, was hired to conduct. And wunderkind director Markus Bothe was brought on board to carve the original disaster into shape. They test-drove a new version in Europe late last year, and now, after even more surgery, the production is slim, trim and ready for American audiences.

Maybe.

"It's a completely different production," says Bothe during a rehearsal break at the Kennedy Center last week.

"In Covent Garden, the performance was 4 1/2 hours. With us it will be just over three hours." He's also junked director Trevor Nunn's original staging (which called for 17 head-spinning set changes) and replaced it with a single set and an almost minimalist approach. The streamlining has moved the focus back on the music, where it belongs, he says. But the process hasn't been easy.

"It's very hard to make cuts -- it's like chopping off limbs," says conductor Alsop, who is making her debut with the Washington company. "But I think it works well. The music's beautiful; it's very romantic, in a dissonant kind of way, and I think it suits the text and the story line beautifully."

The opera's odyssey began in the early 1990s, when Maw (who now lives in Takoma Park and teaches at Baltimore's Peabody Conservatory) stumbled across the 1982 film of the story, renting it one night on the advice of a friend.

"I was stunned by it," he recalls. "I thought it was a remarkable subject matter, and one which was still so important to us as one of the great horrors and tragedies of the 20th century. It immediately filled me with passion with the idea of writing an opera."

The inspiration came as something of a shock. Maw has been one of Britain's most respected and thoughtful composers for decades, writing in an expressive, accessible style ("my music is very much within the romantic code," he says), and he'd already written two well-received operas. Unpleasant experiences getting them produced in Europe, though, had soured him on the whole genre.

"Often, when opera companies are doing an opera by a living composer, they immediately regard it as theirs -- it's not the composer's anymore," he explains with a slight grimace. "I didn't want to be involved with writing operas again."

But "Sophie's Choice" hit him so hard that he began sketching out a dramatic treatment, eventually sending it to Styron himself and inviting him do the libretto. The novelist declined. "He said, 'I'll leave it to you,' " says Maw. "So I decided to write the libretto myself."

Angelika Kirchschlager O. WatkinsIt was a bold but risky decision. While "Sophie's Choice" is a gripping novel, it's also subtly structured and breathtakingly complex. Things are rarely what they seem, and the ground shifts constantly underfoot. In fact, it's those shifts that propel the drama forward. The line between Brooklyn and Auschwitz shimmers and dissolves, ribald comedy alternates with vicious cruelty, and as Sophie's lies and delusions crumble around her, it's never clear whether she's a hapless victim -- or deeply complicit in the most profound evil of the century.

That ambiguity makes the book (and Sophie herself) fascinating, but it also means that reworking "Sophie's Choice" for the musical stage would be a challenge for even the most experienced dramaturge. As a neophyte, Maw took a cautious, almost reverential approach to the text.

He clung tightly to the book's structure, chopping most of the humor ("I just took those parts which are very much related to the subject matter," he says) and using almost nothing but Styron's original words.

The result, some critics have suggested, is less an opera than a "sung novel." While that may have been true for the original production, Bothe insists that the new, streamlined version has punched up the stage drama, while giving the music more room to express the crucial psychological drama.

And that may be its saving grace. The opera's score (as heard in rehearsal last week) is complex. It is romantic and at times almost expressionist in style. At turns playful, brutal, mysterious and explosive, the music has elegant torrents of passage work in the winds, and vocal writing that attempts to recapture the love, rage and agony that are the lifeblood of Styron's novel.

"It's very dark, restless music," Alsop says. "Paradoxical, enigmatic, ambiguous -- one is slightly uncomfortable the whole time. The dramatic moments are very dramatic, and they're very lush -- almost cinematic, in a way. But it's not a sentimental piece at all, and that's important -- it doesn't treat any dimension of this story in a trite or simplistic way."

With "Sophie's" American premiere a day away, Maw is confident. It's a "very American" story, he says, and the subject of the Holocaust is compelling and still relevant. And perhaps most important, the story, for all its tragedy, is a story about the redemptive power of a great and passionate love.

And for Maw, that's the key. "If you're going to write an opera, it has to include passion," says Maw. "Otherwise," he adds softly, "it's not opera."

Sophie's Choice by the Washington National Opera is at the Kennedy Center Sept. 21, 24, 27, 30 and Oct. 5 and 9. For more information call 202-295-2400.or visit http://www.dc-opera.org .

© 2006 The Washington Post Company