"The Universe Resounds": Mahler's Final Triumph

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • June 8, 2006

_______________________________________________________________________________

If you've been taking your time getting tickets to performances of Gustav Mahler's colossal Eighth Symphony -- more famously known as the "Symphony of a Thousand" -- you may be out of luck: Seats for all three of the National Symphony Orchestra's performances this week have been sold out for nearly a month.

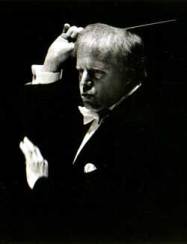

Gustav Mahler"It's a spectacle -- it's larger than life," says NSO Music Director Leonard Slatkin, explaining how the famously neurotic Mahler has become the hottest ticket in town. "Because of its sheer size, it just isn't done very often -- and for a lot of people, this will be a once-in-a-lifetime experience."

But even Slatkin and company have been caught off guard by the interest in the work, which opens tonight at the Kennedy Center. For the past few weeks, they've been furiously pulling the massive piece together, and while there won't be literally a thousand performers onstage (the nickname was a gimmick cooked up by an early impresario), the assembled forces are still staggering: eight soloists, an adult chorus of 314 singers, a children's chorus of 60 and a beefed-up orchestra of about 120 (including multiple harps, a pianist and at least one mandolin), for a grand total of roughly 500 musicians -- one for every five members of the audience.

All those performers, meanwhile, are being arrayed throughout the Concert Hall, from the onstage risers to the chorister boxes and up into the first tier, and the stage itself has been extended a full 20 feet into the audience -- the better to unleash a sonic tsunami that hasn't been heard here since 1988.

"There's no wilder ride than the Mahler Eighth!" says Robert Shafer, sounding partly elated and partly terrified. The Washington Chorus music director has been in rehearsals since March, going over a complex score in which as many as 24 different parts are sung simultaneously. "And in this performance the big parts are going to be incredible," he adds, "because the audience will be surrounded with the music."

But make no mistake -- the music, not the sheer numbers, is the real draw. Passionate, transcendental and unabashedly joyous, the Eighth is a full-throttle affirmation of life -- on a par, many believe, with Beethoven's Ninth. Mahler himself certainly thought so. "It is something the world has never heard the likes of before," he wrote to a friend in 1906, shortly after finishing the work. "Imagine the universe beginning to ring and resound. There are no longer human voices, but planets and suns revolving in their orbits."

Megalomaniacal? Not really, says Mahler biographer Henry-Louis de La Grange, who has spent more years studying Mahler's life than Mahler spent living it. The splendor of the Eighth, La Grange says, embodies an optimistic side of the composer that was almost never seen -- but is just as real as his more notorious dark side. "He was in a state of real ecstasy when he wrote that symphony," says La Grange in a telephone interview from his home in Switzerland. "And it's a great spiritual statement -- a message of hope for humanity as a whole. Some people find it hard to understand, because they feel that Mahler has to be morbid or he isn't Mahler -- but that is just simply wrong!"

The work itself is oddly structured; Mahler himself called it "peculiar." It unfolds over two movements, which at first glance couldn't be more different. The first is a jubilant, tightly woven symphonic movement based on the hymn "Veni, Creator Spiritus" by a 9th-century archbishop named Hrabanus Maurus. The movement's choral text is in Latin, and the contrapuntal style harks back to Bach or even further.

But the second movement is fully of the 19th century, and on a dark night it could almost be mistaken for an opera. Based on the final scene of Goethe's "Faust" -- with its quasi-mystical meditations on forgiveness, love and heavenly bliss -- it's much more modern in style and harmony than the first part. Moreover, it's twice as long. And it's in German.

Yet Mahler unites this unlikely pairing seamlessly; musical elements from the first part reemerge in the second in subtle but unmistakable ways, and the surging energy of the hymn leads ineluctably into the more complex material of the "Faust" section, which in turn builds to an overwhelming, triumphal climax -- what La Grange calls "one of the most glorious moments in music."

"Musically, it works," says Slatkin, who sees the themes of love and redemption as unifying the symphony. "Mahler simply saw a parallel in the subject of redemption and the celebratory nature of the human spirit after death."

For all its joy, though, the Eighth's own history has been bittersweet. After writing it in a burst of inspiration in the summer of 1906, Mahler conducted the premiere himself four years later in Munich. And by all accounts, it was one of the major cultural events of the decade. The leading intellectuals of the day (including composers Richard Strauss, Anton Webern and Camille Saint-Saëns, and writers Thomas Mann and Stefan Zweig) were there, and the ovation at the end was thunderous -- a "collective frenzy," says La Grange, with the audience shouting "Long live Mahler!" for more than 20 minutes.

The triumph was long overdue; while revered as a conductor, Mahler the composer was widely ignored. But the Eighth came too late for him. "It was the greatest success he ever had, and one of the great successes in the history of music," La Grange says. "If he hadn't died so soon after, it would have changed his life."

Slatkin: a larger than life spectacleThat life, though, was already in a tailspin. His 5-year-old daughter Maria had died in 1907, his directorship of the Vienna Court Opera had come to an end, and his beautiful but difficult young wife, Alma, had taken a lover. Perhaps worst of all, he'd been diagnosed with the heart ailment that would soon kill him.

To one observer at the Munich premiere, a specter was hanging over Mahler, even as the cheers resounded through the hall. "Look at those eyes!" he said. "That's not the expression of a triumphant general marching towards new victories. It's the expression of a man who already feels the weight of death on his shoulders." Eight months later, at the age of 50, Mahler was gone.

And for the next few decades, he stayed gone. But conductor Leonard Bernstein began championing him in the 1960s, launching Mahler's posthumous rise to superstar status. And now his music seems everywhere, from sold-out concert halls to film and television scores. And in the ultimate accolade of our time, he was immortalized in "Peanuts" -- when Peppermint Patty, looking battered at the end of a concert, explained that she'd just been "Mahlered."

Not everyone is smitten, of course -- Stravinsky hated his music, and Vaughan Williams snarkily dismissed him as "a very tolerable imitation of a composer."

And among prominent skeptics once was none other than Slatkin himself.

"I used to hate Mahler!" he says, laughing about being dragged in his forties to a Mahler concert, before the music began to take hold. "You have to indulge yourself in the extrovert nature of what Mahler does. And the Eighth is one of the first pieces where I began to understand where his genius lies."