Alexis Descharmes at the Cage Centennial Festival

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • September 6, 2012

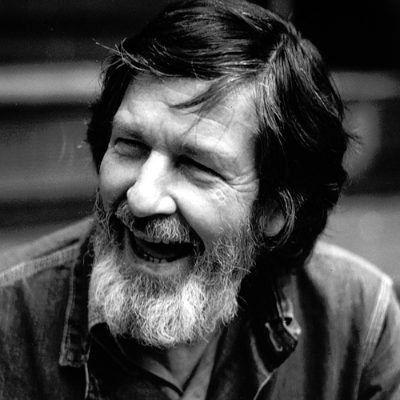

The volcanically innovative composer/writer/artist John Cage — whose legacy is being celebrated across Washington this week in a not-to-be-missed festival of concerts, lectures and exhibits — would have been 100 years old Wednesday night, and to mark the event the French cellist Alexis Descharmes and a stellar cast of friends put on a tribute to the composer at La Maison Francaise. It was, in fact, a very Cageian evening, integrating the composer’s music with visual art, the spoken word, a bit of theater, and the work of other musicians who influenced and were influenced by Cage himself. John CageDescharmes opened the evening by entering a pitch-black stage and, in a quiet tribute to Cage, lighting a flame and launching into the “Solo for Cello” from 1957-58. The piece is quintessential Cage; a succession of spare, beautiful sounds that emerge out of silence, float for a moment and vanish. It’s music pared away to sound itself, purified of narrative or emotion or contrived human drama. Cage’s music isn’t easy; it needs to be met on its own dauntingly simple terms. But to do that is to discover music that’s utterly authentic, transcendent and full of a strange and almost unfathomable beauty.

John CageDescharmes opened the evening by entering a pitch-black stage and, in a quiet tribute to Cage, lighting a flame and launching into the “Solo for Cello” from 1957-58. The piece is quintessential Cage; a succession of spare, beautiful sounds that emerge out of silence, float for a moment and vanish. It’s music pared away to sound itself, purified of narrative or emotion or contrived human drama. Cage’s music isn’t easy; it needs to be met on its own dauntingly simple terms. But to do that is to discover music that’s utterly authentic, transcendent and full of a strange and almost unfathomable beauty.

To these ears, though, the impact was diminished by Descharmes’s curious decision to accompany the work with a soundtrack of a crackling wood fire. Kudos for boldness and all that, but Cage’s sound-world is based in silence perhaps more than that of any other composer, and the noise proved distracting more than illuminating. Similarly, Cage’s “Music for Two” (played with violinist Irvine Arditti), was brilliantly performed, but an overhead slideshow of art by Gerhard Richter kept demanding attention, and Cage, alas, just doesn’t work as music for multitasking. Alexis DescharmesThose quibbles aside, the concert was often illuminating. Erik Satie was a key influence on Cage, and the short, beguiling “Gnossiennes” and “Gymnopedies” — whose melodies seem to float like mobiles in a breeze — were linked to Cage’s music throughout the evening. The Austrian composer Beat Furrer contributed a gorgeous, quiet, deep-moving tribute titled “ferner Gesang” (“distant song”) that had the weight of a sonic sculpture, and a worshipful letter from Pierre Boulez to John Cage was read aloud, the young Boulez urging Cage to remain “elusive” as long as possible. Another tribute, Klaus Huber’s “. . . ruhe sanft. . .” (“. . . rest gently . . .”), written shortly after Cage’s death in 1992, was a poignant if sometimes creepy work that used amplified breathing sounds and the name “John” repeated in a questioning voice.

Alexis DescharmesThose quibbles aside, the concert was often illuminating. Erik Satie was a key influence on Cage, and the short, beguiling “Gnossiennes” and “Gymnopedies” — whose melodies seem to float like mobiles in a breeze — were linked to Cage’s music throughout the evening. The Austrian composer Beat Furrer contributed a gorgeous, quiet, deep-moving tribute titled “ferner Gesang” (“distant song”) that had the weight of a sonic sculpture, and a worshipful letter from Pierre Boulez to John Cage was read aloud, the young Boulez urging Cage to remain “elusive” as long as possible. Another tribute, Klaus Huber’s “. . . ruhe sanft. . .” (“. . . rest gently . . .”), written shortly after Cage’s death in 1992, was a poignant if sometimes creepy work that used amplified breathing sounds and the name “John” repeated in a questioning voice.

Descharmes was accompanied brilliantly throughout the evening by pianist Jenny Lin, clarinetist Bill Kalinkos and violinist Lina Bahn. But the high point of the evening may have been when percussionist Steven Schick joined the cellist for Cage’s “Etudes Boreales” from 1978. Using the piano body and strings as percussion devices, Schick played with extraordinary precision and electricity, and the work burst spectacularly into life — as fine a performance of Cage as you could hope to hear.

Reader Comments