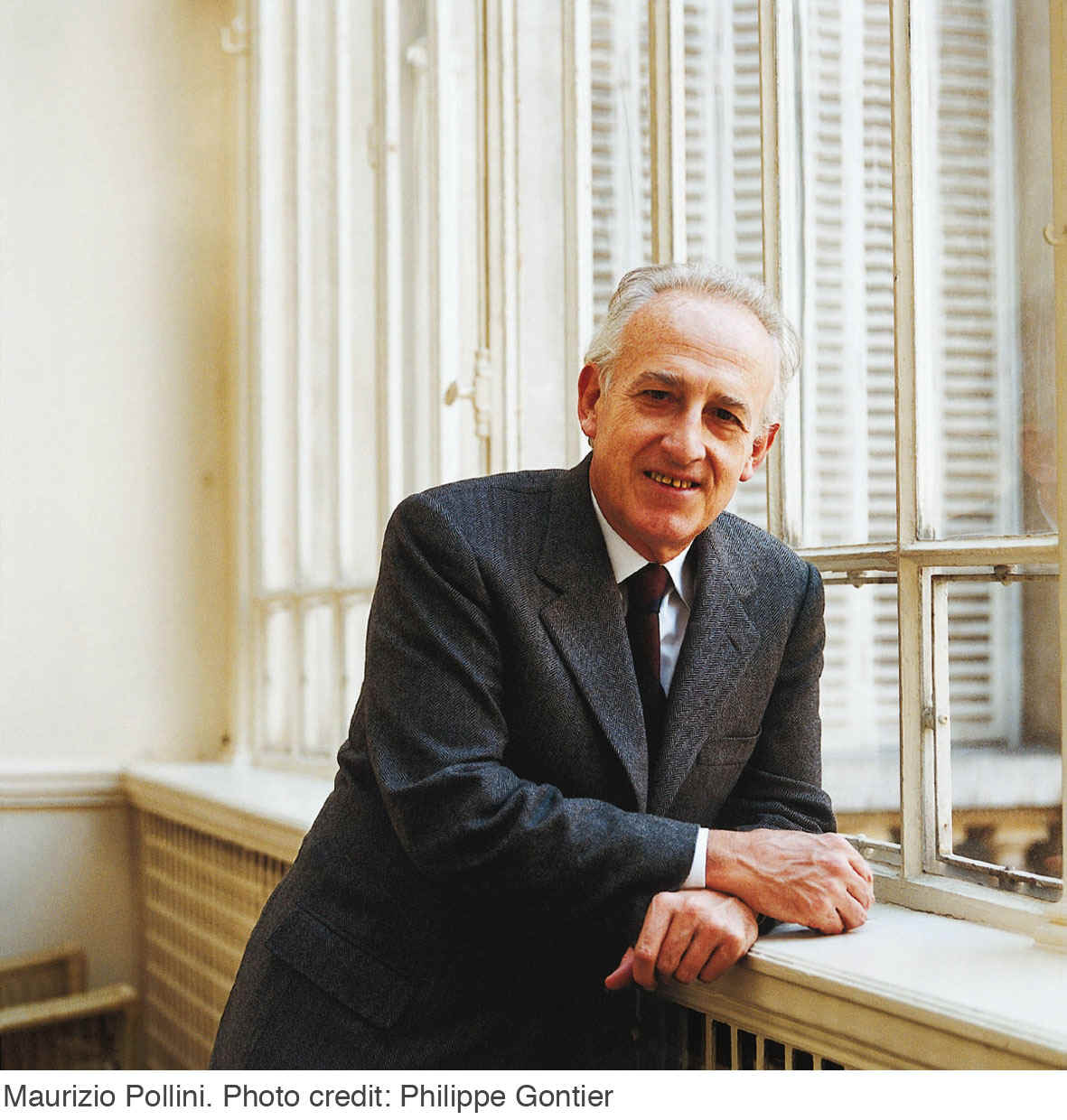

Maurizio Pollini at Strathmore

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • April 15, 2013

Love him or hate him, Maurizio Pollini has been one of the defining — and most polarizing — pianists of the last 50 years. His razor-sharp technique and modern, cooly intellectual approach to music have won legions of admirers, while his detractors hear austerity and a sort of bloodless, clinical detachment. But Pollini’s mastery of the keyboard is beyond reproach, and it was little wonder that the Music Center at Strathmore was packed Sunday afternoon for a program of Chopin and Debussy that — though it may not have converted agnostics — showed the 71-year-old Pollini is still provocative, still polarizing and still very much a force to be reckoned with. The first half of the afternoon was devoted to Chopin, a thoughtfully balanced mix that included the Prelude in C-sharp Minor, the second and third Ballades, the Four Mazurkas, Op. 33 and the Scherzo in C-sharp Minor, Op. 33. And, as expected, Pollini approached them with clear-eyed intelligence and an almost tangible sense of purpose, paring the music to its essentials with clarity and precise, microscopically calibrated detail.

The first half of the afternoon was devoted to Chopin, a thoughtfully balanced mix that included the Prelude in C-sharp Minor, the second and third Ballades, the Four Mazurkas, Op. 33 and the Scherzo in C-sharp Minor, Op. 33. And, as expected, Pollini approached them with clear-eyed intelligence and an almost tangible sense of purpose, paring the music to its essentials with clarity and precise, microscopically calibrated detail.

Some of the works responded to this treatment better than others (the concluding scherzo, in particular, was a fiery delight) and it was impossible not to be impressed. But it seemed equally difficult, in all frankness, to be genuinely moved. Despite the pearly tone and impeccable technique, there was little sense of spontaneity or warmth, no mystery and only the faintest impression of personal involvement. It felt as if Pollini were skillfully revealing each subtle layer of Chopin’s music — and then missing the beating heart at its core.

But any sense of disappointment was dramatically dispelled in the second half of the program. The first book of Debussy’s “Preludes” are among the most chimerical, delicately shaded works in the piano literature, and it was an open question whether they would wilt in Pollini’s steely grip. In fact, they blossomed. His phrasing, unforgiving in the Chopin, loosened and became far more supple and spontaneous, and he brought such vivid detail and imagination to the “Preludes” — from the subtle play of light and shadow in “Voiles” to the gentle lyricism of “La fille aux cheveux de lin” — that they seemed to burst uncannily into life. Even the most die-hard Pollini skeptic would have left impressed.

Reader Comments