Leon Fleisher at the Library of Congress

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • March 9, 2012

When the legendary pianist Leon Fleisher lost the use of his right hand in the early 1960s, putting an end to any ordinary performing career, the composer Dina Koston urged him to take up conducting instead. The advice led to a new direction for Fleisher and a close and lasting friendship with Koston — a friendship that was palpable on Thursday night at the Library of Congress, where Fleisher mounted a deeply-felt tribute to Koston that ranged from the profundities of Bach to some cheerfully unbuttoned vocal music by Gyorgi Ligeti. The evening opened with Fleisher (who regained the use of his right hand about 10 years ago) performing “Messages” for solo piano, a piece Koston wrote for him shortly before she died in 2009. It’s a pensive, richly-colored set of variations, deeply personal and among Koston’s more impressive works, and Fleisher played it with an almost unbearable sense of love and respect; you felt as if you were listening in on an intimate communion between the two.

The evening opened with Fleisher (who regained the use of his right hand about 10 years ago) performing “Messages” for solo piano, a piece Koston wrote for him shortly before she died in 2009. It’s a pensive, richly-colored set of variations, deeply personal and among Koston’s more impressive works, and Fleisher played it with an almost unbearable sense of love and respect; you felt as if you were listening in on an intimate communion between the two.

The affection continued with Brahms’s “Liebeslieder Waltzes for voices and piano, four hands, op. 52,” for which Fleisher was joined by his wife, Katherine Jacobson Fleisher, and four singers from the Peabody Institute. The performance never quite achieved that miraculous glow that you look for in Brahms, but there was much admirable singing; tenor Jayson Greenberg, who did most of the heavy lifting, was particularly impressive.

But the most indelible moments of the evening came when Fleisher performed the Chaconne from Bach’s Partita for unaccompanied violin in D minor, transcribed by Brahms as a piano work for the left hand. His right arm motionless at his side, Fleisher turned in an absolutely spellbinding performance that built steadily, with a kind of distilled, august power, to a breathtaking climax. At 83, Fleisher’s technique may not be as immaculate as it once was, but his musicianship — as the Bach proved — is nothing short of Olympian.

The evening closed on a comic note, with two freewheeling works by Ligeti from the early 1960s. “Aventures” and “Nouvelles Aventures” are a little cartoonish to 21st-century ears but great fun nonetheless, as three vocalists squeak, laugh, sob, hiss, growl and otherwise avoid anything like traditional singing, over an instrumental background of crashing glass, popping paper bags and newspapers being carefully torn to shreds. Kudos to soprano Bonnie Lander, mezzo-soprano Diane Schaming and baritone James Rogers, who turned in gleefully uninhibited performances while Fleisher led the ensemble through this wonderful stuff with deadpan aplomb.

Dina Koston Tribute at the Library of Congress

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • March 8, 2012

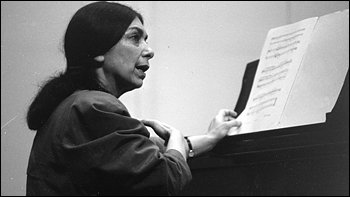

The composer and pianist Dina Koston was one of the driving forces behind new music in Washington for decades, launching the Theater Chamber Players — the Kennedy Center’s first resident chamber ensemble — in 1968, and performing and promoting young composers widely before her death in 2009. That legacy is continuing with a new endowment at the Library of Congress called the Dina Koston and Roger Shapiro Fund for New Music, and on Wednesday the library opened a two-day tribute to Koston with a performance by the Cygnus Ensemble that featured her final work — paired with a short play by Samuel Beckett that inspired it — and a premiere of the endowment’s first commission. Dina Koston“Ohio Impromptu” is quintessential Beckett: minimal and elementally powerful. A haunting meditation on loss, memory and regret, it received a finely shaded performance by Ted van Griethuysen and Steve Nixon. Koston’s “Distant Intervals” for chamber ensemble, which immediately followed, was inspired by the play, but you needed to scrunch your ears up a bit to hear the connection. In contrast with the monochromatic tone and spare, coiled drama of the Beckett play, Koston’s piece was colorful and discursive, a kaleidoscope of ideas posed and questioned, of wistful fragments that rose and subsided and rose again, always changing.

Dina Koston“Ohio Impromptu” is quintessential Beckett: minimal and elementally powerful. A haunting meditation on loss, memory and regret, it received a finely shaded performance by Ted van Griethuysen and Steve Nixon. Koston’s “Distant Intervals” for chamber ensemble, which immediately followed, was inspired by the play, but you needed to scrunch your ears up a bit to hear the connection. In contrast with the monochromatic tone and spare, coiled drama of the Beckett play, Koston’s piece was colorful and discursive, a kaleidoscope of ideas posed and questioned, of wistful fragments that rose and subsided and rose again, always changing. The Cygnus EnsembleChester Biscardi’s delicate and beautiful “Resisting Stillness” for two guitars opened the second half of the program, which also featured Koston’s borderline-cutesy “A Short Tale” for soprano and piano, the gentle “Berceuse elegiaque” by Ferruccio Busoni and Frank Brickle’s “Farai un vers.” But by far the freshest and most original work on the program was David Claman’s “Gone for Foreign.” Written during a stay in India, it’s a collection of vibrant, wildly evocative pieces — a little messy around the edges but told in a wonderfully warped and completely engaging musical language. An intriguing composer worth hearing more from.

The Cygnus EnsembleChester Biscardi’s delicate and beautiful “Resisting Stillness” for two guitars opened the second half of the program, which also featured Koston’s borderline-cutesy “A Short Tale” for soprano and piano, the gentle “Berceuse elegiaque” by Ferruccio Busoni and Frank Brickle’s “Farai un vers.” But by far the freshest and most original work on the program was David Claman’s “Gone for Foreign.” Written during a stay in India, it’s a collection of vibrant, wildly evocative pieces — a little messy around the edges but told in a wonderfully warped and completely engaging musical language. An intriguing composer worth hearing more from.

The choice of Mario Davidovsky as the first recipient of a commission from the Koston Fund, on the other hand, was a bit of a disappointment. Not that he’s a bad composer; his “Ladino Songs” were elegantly done and polished to a fine gleam, which is what you’d expect from a well-established composer in his late 70s with a Pulitzer and positions at Harvard and Yale under his belt. It’s all well and good to honor the elders — but why not aim that funding at young composers out there on the front lines?

Roger Wright at the National Gallery of Art

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • February 27, 2012

Anyone feeling a little trampled by the thundering herds of virtuosi around town these days would have done well to head down to the National Gallery of Art on Sunday night, where pianist Roger Wright put on a program of impressionistic works that was remarkable for its extraordinary freshness, subtlety and originality of thought. It’s hard to over-praise the relatively unknown Wright; his technique is powerful and honed to a razor-like edge, but even more impressive is the rare spontaneity and vitality in his playing — and the sense of a voraciously hungry mind. Wright (who, curiously, is also a Scrabble virtuoso who won the national championship in 2004) alternated lighter and darker pieces throughout the evening. Charles Tomlinson Griffes’s shimmering, chromatic 1915 work “The White Peacock” was balanced against the propulsive “Masks” (1980) by the American composer Robert Muczynski, while the simple melodies and drifting arpeggios of Scott McClain’s “Snow” played to great effect against the infinite complexities of Debussy’s “Masques” and “L’Isle joyeuse.”

Wright (who, curiously, is also a Scrabble virtuoso who won the national championship in 2004) alternated lighter and darker pieces throughout the evening. Charles Tomlinson Griffes’s shimmering, chromatic 1915 work “The White Peacock” was balanced against the propulsive “Masks” (1980) by the American composer Robert Muczynski, while the simple melodies and drifting arpeggios of Scott McClain’s “Snow” played to great effect against the infinite complexities of Debussy’s “Masques” and “L’Isle joyeuse.”

Wright played them all with riveting detail and insight, but the centerpiece of the evening was a reading of Maurice Ravel’s 1908 “Gaspard de la nuit” that was about as fine a performance of this pianistic tour de force as you could ever hope to hear. Wright seemed exceptionally attuned to its elusive, otherworldly beauties, from the delicately shaded “Ondine” movement to the wild and almost frightening “Scarbo” that closes the work.

Wright then cleared the air with Frederic Rzewski’s colorful reworking of “Down by the Riverside” and Mily Balakirev’s finger-breaking “Islamey Oriental Fantasy,” a showstopper played with both precision and explosive fire. That brought Wright a sustained standing ovation, but it may have been the encore — Rachmaninoff’s Prelude in D, Op. 23 No. 4 — that stole the show, with a quiet, understated lyricism that went straight to the heart.

The Emerson String Quartet at Strathmore

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • February 16, 2012

There was a tang of electricity in the air at the Music Center at Strathmore on Wednesday night — but there always is when the Emerson String Quartet is in town. Nearly four decades of playing together have made this one of the most insightful chamber music groups on the planet, and the near-telepathic unity of their interpretations can seem almost miraculous. But there was a note of poignancy in the air as well, for just the day before, cellist David Finckel had announced he would be leaving at the end of the 2012-2013 season — the first member to leave in 34 years. If the news had dampened the group’s spirits, though, it didn’t show. Haydn’s witty Quartet in F Major, Op. 77, No. 2 opened the program, and the Emersons turned in an absolutely engaging reading, full of Haydn’s magnificent, endlessly generous intelligence.

If the news had dampened the group’s spirits, though, it didn’t show. Haydn’s witty Quartet in F Major, Op. 77, No. 2 opened the program, and the Emersons turned in an absolutely engaging reading, full of Haydn’s magnificent, endlessly generous intelligence.

Pianist Wu Han (dressed in such a billowing, colorful outfit that it looked like a giant butterfly had taken the stage) joined Finckel, violinist Philip Setzer and violist Lawrence Dutton for a sweeping account of Brahms’s Piano Quartet in G minor, Op. 25. It’s always a revelation to hear the Emersons play Brahms; they’ve sometimes been accused of being a bit bloodless in their approach to the romantics. But for those who find Brahms a little — shall we say — overstuffed, the group’s expressive conciseness only enhances the impact. And this was, in every sense, a juggernaut of a performance, building relentlessly to the fierce, roiling “Rondo in Hungarian Style” that closes the work.

Eugene Drucker returned to the stage to take the lead violin role in Schumann’s Piano Quintet in E-flat Major, Op. 44. It was a fine choice to end the program: as deep and involving as the Brahms, but more open and full of light — and played with perfectly paced restraint that made it never less than gripping.

Kalichstein-Laredo-Robinson Trio at the Terrace Theater

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • February 15, 2012

Among the superstars of the chamber music world, few induce as much open-mouthed rapture as the Kalichstein-Laredo-Robinson Trio, which arrived in town Tuesday as part of the Fortas Chamber Music Series at the Kennedy Center’s Terrace Theater. On their own, these are don’t-miss performers, but thrown into the bargain were violist Michael Tree and bass player Harold Robinson for a fascinating program that paired Schubert’s much-loved “Trout” quintet with a new piece (inspired by the Schubert work) by Ellen Taaffe Zwilich. Things got off to a feisty start with Beethoven’s Piano Trio No. 4 in B-flat, Op. 11. It’s full of the easy charm you often find in his early music, but there’s a finely honed edge to it, too. Building on a popular tune of the day, Beethoven wallows mischievously in its empty-headedness before sticking his knife in, giving it a little twist and raising the whole thing to perfection. The Trio played it with terrific subtlety and wit, and — of course — spectacular virtuosity.

Things got off to a feisty start with Beethoven’s Piano Trio No. 4 in B-flat, Op. 11. It’s full of the easy charm you often find in his early music, but there’s a finely honed edge to it, too. Building on a popular tune of the day, Beethoven wallows mischievously in its empty-headedness before sticking his knife in, giving it a little twist and raising the whole thing to perfection. The Trio played it with terrific subtlety and wit, and — of course — spectacular virtuosity.

But the showpiece of the evening was Zwilich’s “Quintet for Violin, Viola, Cello, Contrabass, and Piano.” She wrote it for the same instruments as Schubert’s “Trout” Quintet and took her inspiration from the same source, but the piece turned out to be a different kettle of fish entirely. Where Schubert’s trout plays happily in calm and limpid waters, glinting in the summer sun, Zwilich’s is named “Die Launische Forelle” — “The Moody Trout” — and churns and thrashes its way darkly upstream.

It’s an interesting conceit, and Zwilich is no slouch as a composer. But she is a fairly mainstream thinker who’s never made much use of vernacular music, and her use of blues and jazz elements to evoke the moody trout sounded a bit contrived, with more than a whiff of academia about it. Far more convincing was the Schubert, which closed the program. Not his most accomplished music, perhaps, but this was a superb performance, full of warmth and light and an almost overpowering optimism that washed away the vestiges of Zwilich’s ersatz blues.

Joshua Bell at the Kennedy Center

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • January 24, 2012

Washington has had a slightly awkward relationship with Joshua Bell ever since that morning five years ago when — in a now-famous social experiment dreamed up by Post columnist Gene Weingarten — the violin superstar spent a morning busking for coins at the L’Enfant Plaza Metro station, only to be ignored by virtually everyone who passed. Bell, happy to say, took it all in stride, and on Monday night returned to Washington for a more venue-appropriate concert at the Kennedy Center Concert Hall, where he showed that — commuter indifference notwithstanding — he’s one of the most imaginative, technically gifted and altogether extraordinary violinists of our time. Bell is in his mid-40s now, but there’s still a sort of elfin quality to his playing. There’s the trademark untucked shirt, the dancing on the balls of the feet, the mop of flying hair. But in a program that ranged from Mendelssohn to Gershwin, it became clear that there’s also an almost effortless freshness in his playing: It sounds utterly spontaneous, while underpinned with a flawless sense of drama and narrative line. Brahms’s Sonata No. 3 in D Minor, Op. 108, for instance, can sound a bit gelatinous in more ordinary hands, but Bell made it as lucid and weightless as thought, playing (as he did all evening) with an impossibly light touch, evocative tone and pinpoint accuracy — particularly in the closing movement, the Presto agitato, which blew by at something beyond warp speed.

Bell is in his mid-40s now, but there’s still a sort of elfin quality to his playing. There’s the trademark untucked shirt, the dancing on the balls of the feet, the mop of flying hair. But in a program that ranged from Mendelssohn to Gershwin, it became clear that there’s also an almost effortless freshness in his playing: It sounds utterly spontaneous, while underpinned with a flawless sense of drama and narrative line. Brahms’s Sonata No. 3 in D Minor, Op. 108, for instance, can sound a bit gelatinous in more ordinary hands, but Bell made it as lucid and weightless as thought, playing (as he did all evening) with an impossibly light touch, evocative tone and pinpoint accuracy — particularly in the closing movement, the Presto agitato, which blew by at something beyond warp speed.

Mendelssohn’s Sonata in F, with which Bell opened the program, brought a warm dose of sweetness to the evening, and a Jascha Heifetz arrangement of Gershwin’s Three Preludes gave Bell room to display his considerable musical charm. More interesting, though, was the austere and technically daunting Sonata No. 3 in D Minor, Op. 27, “Ballade,” a work for solo violin by Eugene Ysaye. Bell negotiated its complex passage work and double- and triple-stops with aplomb, in a gripping, deeply felt performance.

To these ears, though, the most perfect moments of the evening came in Ravel’s Sonata in G for Violin and Piano. Accompanied by the very astute pianist Sam Haywood, Bell turned in a ravishing reading, a marvel of evanescent colors, shimmering light and the compelling, elusive beauty of a dream.

Steven Honigberg at Dumbarton

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • January 22, 2012

Does it take a village to raise a cellist? Steven Honigberg — a highly regarded member of the National Symphony Orchestra’s cello section — might well agree. In an intriguing and deeply personal recital Saturday at Georgetown’s Dumbarton Church, Honigberg presented an evening of music that reflected the varied influences other cellists have had on his path, from mentors Maurice Gendron and Mstislav Rostropovich to performer-composers such as Marin Marais and Gaspar Cassado. The result was an unabashedly affectionate homage to the cello itself — its deep-voiced intensity, its dark and brooding sonorities, its infinitely subtle beauties — that favored conviction and intimate expression over flashy virtuosity. Accompanied by the always-engaging Audrey Andrist on piano, Honigberg opened with Marais’s “La Folia,” playing with a lean, almost sinewy tone that fit the baroque style well while avoiding the astringency that period hard-liners often adopt. That was followed by an almost confessional reading of Debussy’s “Clair de Lune” and two songs by Dvorak, whose sweeping melodic lines soared with precise, dramatic control.

Accompanied by the always-engaging Audrey Andrist on piano, Honigberg opened with Marais’s “La Folia,” playing with a lean, almost sinewy tone that fit the baroque style well while avoiding the astringency that period hard-liners often adopt. That was followed by an almost confessional reading of Debussy’s “Clair de Lune” and two songs by Dvorak, whose sweeping melodic lines soared with precise, dramatic control.

Honigberg showed off his spectacular technique with Cassado’s mischievous, highly caffeinated “Dance of the Green Devil” before returning to the lush romanticism of Schumann’s Five Pieces in the Popular Style, Op. 102, when he seemed most happily in his element.

With each of the works linked in some way to another cellist, it almost seemed as if Honigberg were mining a kind of collective cello unconscious the rest of us barely knew existed. But in the closing work on the program — Brahms’s quietly epic Piano Trio No. 1, Op. 8 in B Major, with James Stern on violin — Honigberg seemed to weave the disparate roots together, balancing passion with reflection and virtuosity with eloquent simplicity; a taut, tightly focused performance that shimmered with intensity.