The Ives Project: Beyond an innovator’s sound, to his spirit

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • October 30, 2011

It was January 10, 1931, and the mood at New York’s Town Hall was turning ugly. Conductor Nicolas Slonimsky had just led the orchestra through “Three Places in New England” by the little-known composer Charles Ives, and had been met with jeers. Things got even rowdier when Slonimsky launched into Carl Ruggles’s dissonant “Men and Mountains,” and when a listener stood up and loudly began to boo, Ives — who had quietly endured the catcalls for his own work — jumped to his feet.

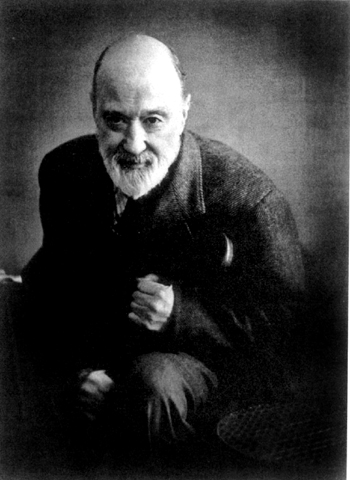

“Stop being such a God-damned sissy!” he shouted at the heckler. “Why can’t you stand up before fine strong music like this and use your ears like a man!” It was one of the more red-blooded moments in American music, and a classic gesture from Ives — a fiercely independent Connecticut Yankee who, though largely ignored in his lifetime, has come to be recognized as one of America’s most remarkable composers. In fact, he may be one of the most visionary — and strangely paradoxical — figures of the 20th century. A modernist who disliked the modern world, a self-made millionaire who championed the common man, Ives isolated himself from the musical world yet came up with virtually all of the innovations of 20th-century music — from wildly intricate rhythms to spacing musicians in different places in the concert hall— long before anyone else. And in the process, he wrote some of the most profound and quintessentially “American” music the world has ever heard.

It was one of the more red-blooded moments in American music, and a classic gesture from Ives — a fiercely independent Connecticut Yankee who, though largely ignored in his lifetime, has come to be recognized as one of America’s most remarkable composers. In fact, he may be one of the most visionary — and strangely paradoxical — figures of the 20th century. A modernist who disliked the modern world, a self-made millionaire who championed the common man, Ives isolated himself from the musical world yet came up with virtually all of the innovations of 20th-century music — from wildly intricate rhythms to spacing musicians in different places in the concert hall— long before anyone else. And in the process, he wrote some of the most profound and quintessentially “American” music the world has ever heard.

“Ives is a larger-than-life personality — a legendary figure, something out of a storybook,” says Joseph Horowitz, a founder of the PostClassical Ensemble. “And he’s indisputably a great spirit.”

Horowitz is the driving force behind the Ives Project, a three-day festival of concerts and discussions this week at the Music Center at Strathmore, that kicks off Thursday with a multimedia “theatrical concert” tracing the composer’s life through his own words and music. Horowitz’s PostClassical Ensemble will be joined by some of the top Ives interpreters in the country — including baritone William Sharp, the Jack Quartet and the rising piano superstar Jeremy Denk — to probe the roots of Ives’s still-controversial music.

“Ives is, in a sense, a very autobiographical composer,” says Denk. “He delves into the magic of things that come from his youth.”

Ives’s iconoclastic path through music began, in fact, almost as soon as he could reach the keyboard. Ives, born in 1874 in Danbury, Conn., was encouraged by his father — the town’s bandmaster — to develop an eclectic, open-minded approach to music. He learned to sing in one key while his father played the piano in another, and was was exposed to a wide range of vernacular music, from hymns and patriotic marches to the ballads of Stephen Foster.

But his father’s key lesson was to ignore the surface appeal of music and look into its deeper meaning. Listening to a stonemason croaking his way through a hymn, he told the boy: “Don’t pay too much attention to the sounds, for if you do, you may miss the music. You won’t get a wild, heroic ride to heaven on pretty little sounds.” Angel Gil-Ordonez will lead the PostClassical EnsembleThe advice stuck. Ives went on to study composition at Yale University but chafed at the convention-bound world of professional music and, after graduating, went into the insurance business instead. It was a crucial decision. Ives turned his back on the musical mainstream and — while building his own hugely successful insurance company — composed feverishly and in isolation for the next several decades, turning out four symphonies, more than a hundred songs, two piano sonatas and a host of other strikingly original works, few of which he ever heard performed.

Angel Gil-Ordonez will lead the PostClassical EnsembleThe advice stuck. Ives went on to study composition at Yale University but chafed at the convention-bound world of professional music and, after graduating, went into the insurance business instead. It was a crucial decision. Ives turned his back on the musical mainstream and — while building his own hugely successful insurance company — composed feverishly and in isolation for the next several decades, turning out four symphonies, more than a hundred songs, two piano sonatas and a host of other strikingly original works, few of which he ever heard performed.

“Ives didn’t have to care about making a living with his music,” says Angel Gil-Ordonez, the music director of the PostClassical Ensemble. “And that gave him the freedom and confidence to write what he felt.”

The result was music that married Ives’s American identity, populist philosophy and musical sophistication into music unlike anything else being written. He drew on the sounds of everyday New England life — popular songs and long-forgotten hymns crop up throughout his music — weaving them into exhilarating, wildly colorful tapestries of sound. Determined to free music from its hidebound conventions, he experimented constantly with polytonality, tone clusters, complex rhythms, collage effects, microtones and a raft of other new techniques long before they became part of the accepted language of modern music.

But Ives’s innovations, Horowitz says, pale beside the spiritual power of his music, which seems to embody the “heroic ride to heaven” his father had pointed him toward. A key work on Thursday’s program, for example, is strange and enigmatic “The Unanswered Question,” in which a trumpet repeatedly poses a five-note phrase described by Ives as “the eternal question of existence.”

“The thing that makes Ives’s music matter is its spiritual dimension — the notion that art is a noble enterprise,” Horowitz says. “It’s true that Ives was almost bewilderingly innovative, but if we use innovation as the most important criterion of his greatness, we diminish him. We’re making a different statement: that Ives was a great spirit and a great human being.”

•••••

The Ives Project

Ives Masterclass with Jeremy Denk

Thursday, November 3, 2011; 4 p.m.; Mansion at Strathmore

Admission: Free (tickets required)

Piano virtuoso Jeremy Denk will guide piano students in the intricacies of performing Ives’ music and mainstays of the American repertoire.

Ives Plays Ives

Thursday, November 3, 2011; 5:30 p.m.; Mansion at Strathmore

Admission: Free (tickets required)

Post-Classical Ensemble Artistic Director Joseph Horowitz and pianist Jeremy Denk present and discuss rare recordings of Ives performing his own music.

Charles Ives: A Life in Music

Jeremy Denk, piano; William Sharp, baritone; Carolyn Goelzer and Floyd King, actors;

Post-Classical Ensemble with Angel Gil-Ordóñez, conductor; written and directed by Joseph Horowitz

Thursday, November 3, 2011; 8 p.m.; Music Center at Strathmore

Tickets $15 - $25 (Stars Price $13.50–$22.50)

Charles Ives: The Unanswered Question

Charles Ives: In the Inn

Charles Ives: Largo Cantabile

Charles Ives: Over the Pavements

Charles Ives songs: ―The Circus Band, ―Memories, ―Feldeinsamkeit, ―Ich grolle nicht, ―Remembrance, ―The Housatonic at Stockbridge, ―General Booth Goes to Heaven, ―Thoreau, ―Down East, ―Cradle Song, ―At the River, ―Serenity, ―The Majority

This theatrical concert weaves music and readings from the composer’s essays and letters in a guided tour through this American original’s life and work—his passionate courtship, his fierce Transcendentalism and his cranky politics. An original script written by Joseph Horowitz helps to define the composer’s life through his relationships with close confidantes, peers and family. This event includes a post-concert discussion with artists and scholars. Performance features Jeremy Denk, piano; William Sharp, baritone; Floyd King and Carolyn Goelzer, actors; and Post-Classical Ensemble with conductor Angel Gil-Ordóñez.

Beethoven and Ives

Jeremy Denk, piano and William Sharp, baritone

Friday, November 4, 2011; 8 p.m.; Music Center at Strathmore

Tickets $15 - $45 (Stars Price $13.50-$40.50)

Charles Ives: Concord Sonata

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 29, ―Hammerklavier‖

The four movements of Ives’ landmark Concord Sonata are dedicated to iconic New England literary figures Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry David Thoreau and the Alcotts. This performance of the work incorporates readings by these great voices of American literature. In tribute to Ives’ lifelong admiration for Beethoven, the concert concludes with Beethoven’s ―Hammerklavier‖ Sonata. The performance features Jeremy Denk, piano and William Sharp, reader. Audience members can join a post-concert discussion with the artists.

Interpreting Ives

Saturday, November 5, 2011; 3:30 - 6:30 p.m.; Music Center at Strathmore, Room 402

Tickets $15 (Stars Price $13.50)

3:30-4:30 p.m.: Lecture/performance with Joseph Horowitz on Ives and the 21st Century; Jeremy Denk on Ives and Beethoven

4:30-5:15 p.m.: Reception and mingling with the artists

5:15-6:30 p.m.: Tom Owens on Ives’ letters; William Sharp performs and discusses the parlor sources of Ives’ songs

In this intimate immersion experience, definitive Ives authorities Joseph Horowitz, Jeremy Denk, Tom Owens and William Sharp build an understanding and image of the celebrated composer by exploring his relevance in the 21st century and relationship to revolutionary musical predecessors.

Ives and Other Innovators -- The Jack Quartet

Saturday, November 5, 2011; 7:30 p.m.; Mansion at Strathmore

Tickets $30 (Stars Price $27)

Philip Glass: String Quartet No. 5

Julia Wolfe: Dig Deep 7

Charles Ives: String Quartet No. 2

Caleb Burhans: Contritus

Tokyo String Quartet at the Kennedy Center

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • October 28, 2011

Over the past 40 years, the Tokyo String Quartet has built a well-deserved reputation for rock-solid ensemble playing and immaculate, razor-edged precision. Those enviable qualities were often in evidence on Wednesday night at the Kennedy Center’s Terrace Theater, where the Tokyos opened the 31st season of the Fortas Chamber Music Series. But the group, to its credit, seems to be loosening up in middle age, allowing the individual players freer rein and focusing on spontaneity rather than polish. That agreeable approach, at any rate, was immediately clear in Mozart’s “Quartet in G major, K. 387,” which the Tokyos played with such relaxed affection that even its darker moments were filled with sunshine and puppies. Roles were quickly defined: first violinist Martin Beaver provided the driving forward edge, anchored by Kikuei Ikeda’s unflappable second violin; cellist Clive Greensmith was the soulful poet of the group; and violist Kazuhide Isomura — the only founding member still left — played solidly if a shade more woodenly than in his younger years.

That agreeable approach, at any rate, was immediately clear in Mozart’s “Quartet in G major, K. 387,” which the Tokyos played with such relaxed affection that even its darker moments were filled with sunshine and puppies. Roles were quickly defined: first violinist Martin Beaver provided the driving forward edge, anchored by Kikuei Ikeda’s unflappable second violin; cellist Clive Greensmith was the soulful poet of the group; and violist Kazuhide Isomura — the only founding member still left — played solidly if a shade more woodenly than in his younger years.

Mozart’s warmth and optimism were balanced by an absolutely gripping account of Karol Szymanowski’s dark, brooding “Quartet No. 1 in C major, Op. 37.” An early modernist work from 1917, it paints a lush, inward-looking and wildly imaginative landscape rife with eerie harmonics and muted sonorities — especially in the scherzo-ish last movement. It's a phenomenal piece, performed far too rarely, and the Tokyos played it ravishingly — helped partly by their extraordinary “Paganini” collection of Stradivarius instruments, which produced a sound so golden and seductive it made your ears go all quivery with love.

The evening closed on a more upbeat note with a hugely entertaining romp through Antonin Dvorák’s Quartet in G major, Op. 106. Written in 1895 — shortly after the composer returned to Prague from his years in America — it has fewer of the ersatz “Americanisms” of his earlier works and more of the earthy, thump-a-dump rhythms of Czech folk music, and (unlike the Szymanowski) there’s nothing in it which might frighten the children. The Tokyo players had great fun with it, diving enthusiastically into its endlessly blossoming melodies and capturing the work’s character with loose, unbuttoned elan.

Eclipse Chamber Orchestra Opens 20th Season

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • October 24, 2011

The Eclipse Chamber Orchestra is known for bringing a sense of community to its musicmaking — interacting with its audiences in small venues, promoting young players, showcasing the work of local composers, even inviting listeners to get-togethers. That warmth was evident on Sunday at the George Washington Masonic Memorial in Alexandria, where the ensemble opened its 20th season with an audience-pleasing selection of pieces that ranged from a baroque obscurity to the very-much-alive music of Mark Adamo. Sylvia AlimenaIt was fitting, in fact, that the concert opened with Adamo’s “Overture to Lysistrata” since it was Music Director Sylvia Alimena who discovered this fast-rising composer while he was a music student at Catholic University and helped launch his career.

Sylvia AlimenaIt was fitting, in fact, that the concert opened with Adamo’s “Overture to Lysistrata” since it was Music Director Sylvia Alimena who discovered this fast-rising composer while he was a music student at Catholic University and helped launch his career.

“Overture” turned out to be a rambunctious work, full of life and noise and nonstop action — great fun, and a jolt of musical caffeine to the ears. It was followed by the Symphony in A by English baroque composer William Boyce, a slight, pleasant work saved from forgettability only by a strangely charming “hiccup” motif in the last movement.

But it was the young Australian violinist Alexandra Osborne — an ECO regular — who stole the show, soloing in Saint-Saens’s virtuosic show-off number, “Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso, Op. 28.” Osborne has an impressive technique and tossed off the pyrotechnics with ease, though she seemed content to turn in an accurate, rather than fiery, account of this white-hot work. It would be interesting to hear her when she’s ready to pull out the stops and show us what she’s really got.

The ECO players performed with their trademark precision all afternoon, but they shone particularly brightly in a beautifully colored reading of Felix Mendelssohn’s Symphony No. 4 in A (the “Italian”). Elegantly nuanced and crisply detailed, it made a fine close to the program.

Emerson String Quartet at the Museum of Natural History

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • October 16, 2011

The Emerson String Quartet is one of the world’s blue-chip chamber groups, so perhaps it wasn’t a surprise that it turned in a superb and often deeply involving performance on Saturday night at the National Museum of Natural History’s Baird Auditorium. What was a little surprising was the relative conservatism of the program — a well-worn path of late works by Mozart and Beethoven — but as it turned out, the conservatism was only skin deep. Playing in their trademark standing positions, the Emersons opened with Mozart’s Adagio and Fugue in C Minor K. 546. Stately and rather formal, it’s not a particularly “Mozartean” piece, and the ensemble didn’t reveal any unexpected beauties in it — though the Fugue, which started with worrying slackness, built to a brilliant and furious close. It was with the composer’s Quartet in D, K. 575, though, that the Emersons displayed the insightful and absolutely crystalline playing that is their hallmark. Everything that you come to Mozart for — the profound logic that integrates every note, the delicate and closely observed emotions, the sly glimpses of the sublime — was there; and though this was not exactly a risk-taking or passionate performance, it shone with intelligence and wit.

Playing in their trademark standing positions, the Emersons opened with Mozart’s Adagio and Fugue in C Minor K. 546. Stately and rather formal, it’s not a particularly “Mozartean” piece, and the ensemble didn’t reveal any unexpected beauties in it — though the Fugue, which started with worrying slackness, built to a brilliant and furious close. It was with the composer’s Quartet in D, K. 575, though, that the Emersons displayed the insightful and absolutely crystalline playing that is their hallmark. Everything that you come to Mozart for — the profound logic that integrates every note, the delicate and closely observed emotions, the sly glimpses of the sublime — was there; and though this was not exactly a risk-taking or passionate performance, it shone with intelligence and wit.

But the real reward came in the second half of the program, which was devoted to Beethoven’s monumental Quartet in B-flat, Op.130, and the Grosse Fuge, Op. 133. And devoted is the word. It’s rare to hear such committed playing from any ensemble, and the Emersons tore so deeply into this work that it rang with jaw-dropping power and authenticity; you could not tear your ears away. And if that were not enough, the concluding Grosse Fuge sounded as if it had been carved with sharp knives; played with the fury of a savage and slightly unhinged god, it was nothing less than astonishing.

Czech composer Miroslav Srnka at the Phillips Collection

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • October 14, 2011

If you want people to listen, don’t shout; whisper. That might be the thinking behind the music of Miroslav Srnka, a young Czech composer who appeared at the Phillips Collection with the Fama Quartet on Thursday night to open the gallery’s Leading European Composers series. Miroslav Srnka / photo Nico Serda Srnka presented three of his recent chamber works for strings, intriguing pieces that explored a sound world of spare, often rough textures and fragile sonorities — and rarely rose above a delicate pianissimo. The evening opened with “Tree of Heaven,” a single-movement string trio from 2010. Named after the tenacious Chinese plant, it opened with a sudden, brutal chord but quickly quieted into a landscape of scratches, insistent tremolos, microtonal slides and other evocative sounds, often at the edge of audibility.

Miroslav Srnka / photo Nico Serda Srnka presented three of his recent chamber works for strings, intriguing pieces that explored a sound world of spare, often rough textures and fragile sonorities — and rarely rose above a delicate pianissimo. The evening opened with “Tree of Heaven,” a single-movement string trio from 2010. Named after the tenacious Chinese plant, it opened with a sudden, brutal chord but quickly quieted into a landscape of scratches, insistent tremolos, microtonal slides and other evocative sounds, often at the edge of audibility.

Srnka’s music isn’t “atonal” so much as “post-tonal”; by making it so quiet, Srnka unveils subtle and wildly complex sonorities, taking the emphasis off the tone and placing it on the sound itself, to striking and beautiful effect. That approach seems to be his signature, for it continued into “That Long Town of White to Cross,” a soliloquy for violin that takes its title and mood from the Emily Dickenson poem “It Can’t Be Summer.”

The composer is fortunate to have exceptional interpreters in the Fama players — also Czech — and violinist David Danel was particularly adept at tying the delicate wisps of sound into a coherent whole. But the high point of the evening may have been the premiere of Srnka’s fourth quartet, “Engrams” — a term my dictionary defines as “a hypothetical permanent change in the brain accounting for the existence of memory.” Srnka juxtaposed his vocabulary of tremolos and dry scuttlings against simple rising and falling lines throughout the one-movement work, creating an elusive, soft-edged but tangible world — much like memory itself.

Alexandria Symphony Orchestra at Schlesinger

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • October 9, 2011

The Alexandria Symphony Orchestra might not be considered among the world’s top orchestras, but don’t tell its players that. Opening this year’s season Saturday night under the baton of Music Director Kim Allen Kluge, the ASO turned in a jaw-dropping performance, premiering a virtuosic cello concerto by David Balakrishnan and infusing Hector Berlioz’s venerable old war horse, the “Symphonie Fantastique,” with so much vitality, electricity and excitement that it sounded like it was written last week. David BalakrishnanThe concert — at the Rachel M. Schlesinger Concert Hall and Arts Center in Alexandria — opened with two works by Balakrishnan, a composer and violinist on the front lines of what’s loosely called “crossover music” — music that incorporates pop genres into classical settings. “Little Mouse Jumps” is a sort of concertino for violin, and Balakrishnan took the lead role on amplified violin. The title, taken from a Native American folk tale, set the mood; it was a playful, almost cartoonishly colorful piece, dipping easily into jazz and blues and skimming agreeably across the surface of any number of genres.

David BalakrishnanThe concert — at the Rachel M. Schlesinger Concert Hall and Arts Center in Alexandria — opened with two works by Balakrishnan, a composer and violinist on the front lines of what’s loosely called “crossover music” — music that incorporates pop genres into classical settings. “Little Mouse Jumps” is a sort of concertino for violin, and Balakrishnan took the lead role on amplified violin. The title, taken from a Native American folk tale, set the mood; it was a playful, almost cartoonishly colorful piece, dipping easily into jazz and blues and skimming agreeably across the surface of any number of genres. Kim Allen KlugeBalakrishnan’s new cello concerto, “Force of Nature,” was a weightier work, written for and performed by Mark Summer, a longtime friend of Balakrishnan’s and co-founder of the Turtle Island Quartet. It’s a tour de force of technique, careening through an eclectic pastiche of styles — big-band show tunes, 1930s Paris and . . . was that Eric Clapton? — that seemed to switch gears every few seconds. Summer kept the momentum barreling forward (his bluesy, improvised cadenza was a highlight), but it was hard to escape the feeling that the composer was weaving genres together not because it made musical sense, but rather to show how well he could do it. The result was a skillful collage, imaginatively done and great fun to listen to, but without a strong identity of its own.

Kim Allen KlugeBalakrishnan’s new cello concerto, “Force of Nature,” was a weightier work, written for and performed by Mark Summer, a longtime friend of Balakrishnan’s and co-founder of the Turtle Island Quartet. It’s a tour de force of technique, careening through an eclectic pastiche of styles — big-band show tunes, 1930s Paris and . . . was that Eric Clapton? — that seemed to switch gears every few seconds. Summer kept the momentum barreling forward (his bluesy, improvised cadenza was a highlight), but it was hard to escape the feeling that the composer was weaving genres together not because it made musical sense, but rather to show how well he could do it. The result was a skillful collage, imaginatively done and great fun to listen to, but without a strong identity of its own.

Kluge has named this year’s program “Season of Dreams,” so it was fitting that opening night included Berlioz’s allegedly opium-induced musical phantasmagoria, “Symphonie Fantastique.” But there was nothing soporific about this performance; Kluge drew a detailed, insightful and spectacularly vibrant interpretation from his players — a world-class performance that made it clear that the orchestra is a force to be reckoned with.

Philip Glass at the Phillips Collection

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Times • October 4, 2011

Philip Glass is one of the most famous names in modern music, a composer whose minimalist, hypnotically repetitive scores have attracted huge audiences over the past four decades - and divided them into warring camps.

On one side are the devotees (it’s not too strong a word) who find Mr. Glass‘ undulating patterns, simple triads and endlessly repeated arpeggios to be music of subtle but transcendent beauty. On the other side is an equally passionate crowd that scorns him as a tedious thumb-twiddler, churning out simplistic mush for slow thinkers. And as Mr. Glass approaches his 75th birthday - still astonishingly prolific - the debate over his importance as a composer continues to rage.

More fuel was thrown on the fire on Sunday, when Mr. Glass himself appeared in town for a rare recital at the Phillips Collection, performing his early works for piano in the museum’s Music Room. And it was, in every way, an extraordinary event. To hear any composer play his or her own works - especially in such an intimate setting - offers the prospect of a direct insight into their music, a chance to hear it as they intended it to sound, without the filter of an outside interpreter.

And it was, in every way, an extraordinary event. To hear any composer play his or her own works - especially in such an intimate setting - offers the prospect of a direct insight into their music, a chance to hear it as they intended it to sound, without the filter of an outside interpreter.

But the results can sometimes be shocking.

Mr. Glass opened with six of his Piano Etudes, a collection that he began writing in 1994 to develop, as he told the audience, his own skills at the piano. The choice was almost embarrassing in its irony, though, for it quickly became clear that Mr. Glass does not play the piano well. In fact, he plays it badly - very badly. The Etudes were a muddle of missed notes, incoherent phrasing and clumsy fingering, banged out with great enthusiasm but only the faintest attention to detail. Mr. Glass is not, of course, a concert pianist and shouldn’t be judged as one; nevertheless, the not-ready-for-prime-time playing didn’t do his music any favors.

But what was perhaps most surprising was his interpretive approach. Mr. Glass‘ music - from iconic, large scale works such as the opera “Einstein on the Beach” and the film score for “Koyaanisqatsi,” to his smaller pieces for solo instruments - all tend to get their power from the gradual, deliberate building of large patterns from small motives. They grow with a kind of organic inexorability (or, as critics would have it, predictable dullness), and have the most impact when performed with a kind of cool, precise detachment that allows the music to unfold as almost a natural phenomenon. It’s music that few would ever think to call Romantic; the idea seems absurd.

And yet, that was how Mr. Glass played it. From the opening Etudes he went on to the engaging “Mad Rush” from 1979 and four movements from his “Metamorphosis” series of 1988, and it was clear that the composer saw these as intensely personal works, bursting with passion and human drama. He sturmed-and-dranged his way through them as if channeling Schubert, painting with a broad brush and a damn-the-details exuberance. The result - to these ears, anyway - was a mess. But it was a happy, crazy, even joyful mess, full of heart if not a lot of sense, and Mr. Glass‘ affection for his own music was contagious. Certainly one of the more unusual recitals of the year, and an intriguing start to the Phillips Collection’s 71st season of Sunday concerts.