Passion at the Washington Early Music Festival

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • July 11, 2011

W

hat’s with the early-music crowd? Doesn’t it know that when you put on a gala, you’re supposed to have champagne, limousines, Balenciaga-dressed celebrities and herds of paparazzi? Alas, there wasn't a single outsized ego at the Washington Early Music Festival’s fundraising gala Saturday night. In fact, there was no pomp at all, just three hours of extraordinary, evocative and often riveting music from some of the area’s most interesting performers. What a drag. Carlo GesualdoMaybe it’s early music’s resolutely anti-glam quality that makes it so appealing; at any rate, the event at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, titled “Vices & Virtues: Music of Passion From Early Europe,” was an almost intimate affair in spite of its large size, with the audience seated closely around the performers. No fewer than nine vocal and chamber ensembles took part, performing secular music from the 13th century (the obscure Blanche de Castille) to the 18th (the less obscure Ludwig van Beethoven), on original instruments.

Carlo GesualdoMaybe it’s early music’s resolutely anti-glam quality that makes it so appealing; at any rate, the event at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, titled “Vices & Virtues: Music of Passion From Early Europe,” was an almost intimate affair in spite of its large size, with the audience seated closely around the performers. No fewer than nine vocal and chamber ensembles took part, performing secular music from the 13th century (the obscure Blanche de Castille) to the 18th (the less obscure Ludwig van Beethoven), on original instruments.

With its focus on historical accuracy, early music can sometimes come across as earnest rather than passionate, and a few performances — Modern Musick’s exacting account of Beethoven’s early Trio Op. 1, No. 3, for instance — felt more intriguing than moving. Allison MondelBut others went straight to the heart. The chamber choir Carmina turned in dark, ravishing accounts of two 16th-century madrigals by composer/wife murderer Carlo Gesualdo; mezzo-soprano Barbara Hollinshead lent drama and humor to a selection of Renaissance love songs; and the awesomely named Suspicious Cheese Lords brought passion and precision to early works from Jean Mouton and Orlando de Lassus.

Allison MondelBut others went straight to the heart. The chamber choir Carmina turned in dark, ravishing accounts of two 16th-century madrigals by composer/wife murderer Carlo Gesualdo; mezzo-soprano Barbara Hollinshead lent drama and humor to a selection of Renaissance love songs; and the awesomely named Suspicious Cheese Lords brought passion and precision to early works from Jean Mouton and Orlando de Lassus.

The most stunning moments came from two singers, one a stalwart of the Washington scene and the other a relative newcomer. Soprano Rosa Lamoreaux has a voice like honey with little silver bells in it (sorry -- there’s just no other way to describe it) and sang a 17th-century motet from Isabella Leonarda with such ear-melting beauty that you wanted to follow her around forever. But the most affecting performance may have come from young soprano Allison Mondel, who brought a kind of spare, otherworldly radiance to the medieval works she sang — a performance from across the centuries, full of distant and irresistible beauties.

Scarlatti and Stella at the Phillips Collection

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • July 2, 2011

Domenico Scarlatti’s dense, explosive little sonatas for harpsichord are some of the most arresting works to come out of the Baroque period. There are more than 500, and most last for only a few minutes; they blossom, deliver a punch to the gut or an enigmatic caress, and vanish. Yet their power is astounding; little music of any era packs such kinetic energy and emotional turbulence into so few notes, as Steven Silverman showed during a short but engaging all-Scarlatti recital at the Phillips Collection on Thursday evening. What made the concert particularly noteworthy, though, was that it took place in a gallery packed with new sculptures by Frank Stella — works that were directly inspired by Scarlatti’s music.

What made the concert particularly noteworthy, though, was that it took place in a gallery packed with new sculptures by Frank Stella — works that were directly inspired by Scarlatti’s music.

Exuberant and wildly colorful, Stella’s metal-and-resin constructions (part of his “Scarlatti K Series”) seem to hurtle through the gallery like exploding dune buggies, and at first the connection to 17th-century harpsichord music seems a little strained. But as the evening unfolded, the similarities emerged: the same hyper-focused energy, the same unsettling edginess, the same sense that a dangerous new beauty had entered the world.

Silverman played well, if cautiously; this was a cerebral rather than fiery performance, too polite and well-behaved for some tastes but thoughtful, nonetheless. Given that the works on display correspond to specific sonatas, it would have been fascinating to hear those particular pieces, but Silverman chose unrelated works. A missed opportunity, perhaps, to explore musically what was taking place in Stella’s head — which would have been a fascinating evening indeed.

Chantry sings Byrd at St Mary Mother of God

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • June 20, 2011

Is the most powerful art made in times of the most adversity? The early-music vocal group Chantry made a strong case for that idea Saturday night in an evening of liturgical music by Renaissance composer William Byrd (a staunch Catholic in militantly Protestant England) that was extraordinarily expressive and even exuberant — despite being written at a time when merely owning papist music was enough to land you in jail. Wolliam ByrdChantry music director David Taylor has been carving adventurous paths for the group for the past decade, and in this performance he combined music from Byrd’s “Gradualia Propers for the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul” and his “Mass for Five Voices.” Byrd wrote the works for clandestine Catholic services at the turn of the 17th Century, under rather tense circumstances: having left the court of Queen Elizabeth (where he was famed for his colorful, secular madrigals), he was isolated in the countryside, subject to fines for his religious beliefs and repeated searches of his house for incriminating materials.

Wolliam ByrdChantry music director David Taylor has been carving adventurous paths for the group for the past decade, and in this performance he combined music from Byrd’s “Gradualia Propers for the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul” and his “Mass for Five Voices.” Byrd wrote the works for clandestine Catholic services at the turn of the 17th Century, under rather tense circumstances: having left the court of Queen Elizabeth (where he was famed for his colorful, secular madrigals), he was isolated in the countryside, subject to fines for his religious beliefs and repeated searches of his house for incriminating materials.

But to judge by Chantry’s performance, the repressive atmosphere may have helped produce some of Byrd’s most intense and personal music. There is nothing distant or High Church about these performances; Taylor pulled robust, characterful readings out of his singers, and if the effect was sometimes more athletic than atmospheric, it also brought edge-of-seat vitality to the music. Chantry navigated Byrd’s intricate counterpoint with precision, and though the acoustics of the venue (St. Mary Mother of God Church on Fifth Street NW) sometimes muddied the details, this was an evening of exceptionally interesting and moving music.

If you missed it, there’s a second chance: Chantry will repeat the program at 7:30 p.m. Saturday June 25 at St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Alexandria.

Art forgeries snare unwary at online auction sites

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Times • June 7, 2011

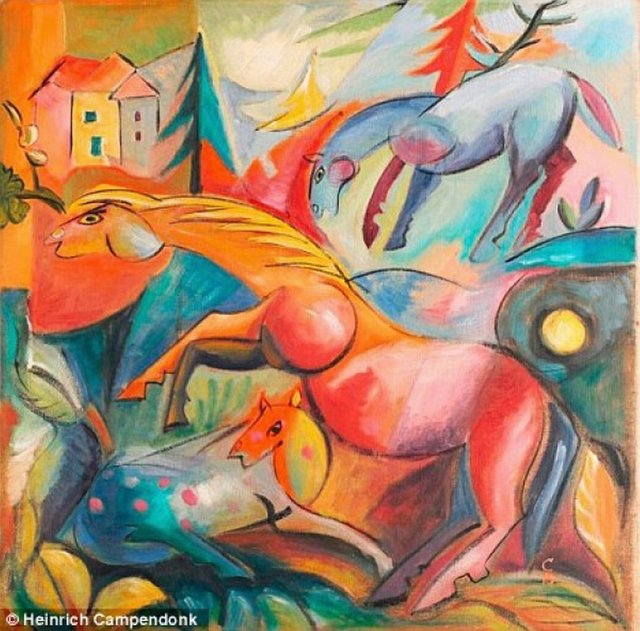

Steve Martin knows his art. The Hollywood star is an experienced, savvy collector and is so familiar with the art world that he even wrote a novel - “An Object of Beauty” - about it. So when Mr. Martin had the chance in 2004 to buy a painting by the early 20th-century expressionist painter Heinrich Campendonk for the bargain price of about $850,000, he jumped on it.

Heinrich Campendonk’s “Landscape With Horses” Bad move. The painting, it turns out, was a forgery - a counterfeit so flawless that even an expert hired to authenticate it had been fooled. Mr. Martin wasn’t the only victim; police say the gang may have sold at least 14 forgeries over the past decade, defrauding galleries and collectors of close to $50 million.

Heinrich Campendonk’s “Landscape With Horses” Bad move. The painting, it turns out, was a forgery - a counterfeit so flawless that even an expert hired to authenticate it had been fooled. Mr. Martin wasn’t the only victim; police say the gang may have sold at least 14 forgeries over the past decade, defrauding galleries and collectors of close to $50 million.

But forgery isn’t just a problem for those in the stratosphere of the art world. Almost anyone can be a victim now, as fakes priced from a few hundred to several thousand dollars regularly show up in auctions, websites and galleries. Over the past 15 years, specialists say, the explosion of new ways to buy art online - particularly through auction sites such as eBay - has brought flocks of inexperienced buyers into the market and made it easier for counterfeiters to find them, fool them, fleece them and forget them.

“It’s pervasive,” said Alan Bamberger, author of “The Art of Buying Art” and a specialist in online art crime. “Twenty years ago, forgers operated on local or regional levels through auction houses that didn’t have art specialists on hand. But these days you can go online and show your masterworks to the world with no problem.”

Fakes make up a small percentage of all available art, Mr. Bamberger said, but it’s still a concern at small auctions and retail shops and a “substantial” problem online. With about 1.5 million works of art at any time on eBay alone, the online auction world is a huge and largely unregulated place where artists, reputable dealers, private sellers and con artists rub shoulders without really meeting.

Most of the art sold is genuine, and bona fide bargains can be found. Authentic works often go for a fraction of their price in bricks-and-mortar galleries, but the fantasy of finding an overlooked treasure - the Degas drawing someone found in the attic and is selling for pennies - still draws in the unwary, and forgers are ready to exploit the demand.

“EBay is a great place to buy fake art,” says Mr. Bamberger, who keeps files of suspicious online sales on his website, ArtBusiness.com. Among the questionable pieces: an alleged Picasso that went for $15,000, a purported Willem de Kooning that reached $17,500 and a watercolor said to be by Pierre Bonnard for $1,237 - all priced well below market value, all lacking documentation, and all almost certainly fake.

“The people who buy this stuff are just as much at fault” as the forgers, Mr. Bamberger said. “If you’re going to go online and beat the bushes for bargains, and you don’t know what you’re looking at, then you’re leaving yourself open to becoming a victim.”

There’s no dearth of crude, easy-to-spot fakes, but others are surprisingly sophisticated. In 2008, Spanish police and the FBI broke up an international ring that sold - mostly on eBay - about $5 million in near-perfect fakes of popular artists including Andy Warhol and Marc Chagall. Other forgers work on a smaller scale by finding paintings in secondhand shops that resemble those by famous artists, then changing signatures, adding antique frames, putting stickers and inscriptions on the backs of canvases, and sometimes adding layers of dust for authenticity.

Although selling forgeries is illegal and auction sites have rules against it, it’s really up to buyers to protect themselves. Mr. Bamberger advises bidders to get as much information from the seller as they can about the origins and background of a piece, and never assume that a piece is genuine just because it is signed - or that they’re the only one who has spotted a bargain. Ask for detailed photos, be suspicious about “Certificates of Authenticity” (they rarely mean much), make sure you have a money-back guarantee, never pay with money orders or wire transfers, and - especially when bidding on high-ticket items - consult with an expert before you bid.

To avoid getting burned, Mr. Bamberger says, it’s best to stick to established galleries and auction houses, where you can get your money back if the piece turns out to be counterfeit. If you must buy art online, educate yourself first.

“If you don’t know what you’re looking at at auction, don’t buy it,” he says. “You have to know what you’re doing, you have to understand art language, you have to know how to pick through a description, you have to know what questions to ask.”

Most of all: Don’t be too trusting. “A skeptical approach,” Mr. Bamberger said drily, “is very healthy.”

Samuel Pisar's 'Kaddish': A warning to the world

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • May 27, 2011

As premieres go, it wasn’t the most promising. When Leonard Bernstein unleashed his sprawling Third Symphony — titled “Kaddish” — on the American public in January 1964, the critics practically trampled each other to get in the first jabs. “There is something enviable about the utter lack of inhibition with which Leonard Bernstein carries on,” sniffed Michael Steinberg in The Boston Globe. The symphony was a work “of such unashamed vulgarity,” he wrote, that listening to it put “a strain on one's credulity.”

But it wasn’t Bernstein’s music that drew the ridicule — it was the cringe-inducing narration he had written, around which the symphony revolves. A Kaddish is a Jewish prayer associated with mourning, and Bernstein had dedicated it to John F. Kennedy, who had been assassinated the previous November. Bernstein tried to grapple with huge spiritual issues in the work, angrily confronting God and demanding an answer to the problem of evil in the world. But the prissy, flowery prose just left listeners giggling into their fists. “A peevish rant,” judged one critic. “Treacly,” said another. “A lava-flow of cliches,” added a third.

But it wasn’t Bernstein’s music that drew the ridicule — it was the cringe-inducing narration he had written, around which the symphony revolves. A Kaddish is a Jewish prayer associated with mourning, and Bernstein had dedicated it to John F. Kennedy, who had been assassinated the previous November. Bernstein tried to grapple with huge spiritual issues in the work, angrily confronting God and demanding an answer to the problem of evil in the world. But the prissy, flowery prose just left listeners giggling into their fists. “A peevish rant,” judged one critic. “Treacly,” said another. “A lava-flow of cliches,” added a third.

“I’ve never seen criticisms such as Kaddish had,” Bernstein told an interviewer a few years later. “In my fervor to make it immediately communicative to the audience, I made it over-communicative,” he said, adding: “Even I am embarrassed when I hear the record.”

Kaddish is coming to the Kennedy Center this week, but don’t worry — conductor John Axelrod, who will be leading the National Symphony Orchestra, has set aside the composer’s original prose in favor of a narration written (and performed) by an extraordinary figure named Samuel Pisar. Pisar, a survivor of the Nazi concentration camps, has completely rewritten the text, turning “Kaddish” into a searing and intensely moving exploration of one of mankind’s greatest horrors.

“Bernstein knew better than anyone that his text was not suited to this symphony,” says Pisar, who wrote his narration after the composer, a close friend, had asked him to in the last weeks of his life. “Lenny told me, ‘I don’t have the credentials to do something serious with this. I’m just dancing around God. But you have lived it in body and soul.’”

Pisar’s life, in fact, has been an extraordinary story of suffering and rebirth. As a child growing up in Poland, he had seen his father tortured and killed by the Gestapo, and at 13 he was sent to the extermination camp of Majdanek, then on to Auschwitz and finally Dachau. He was lucky to survive at all; his mother and younger sister were taken away by the Nazis, never to be seen again.

“In front of the cattle car, at the moment of my separation from my mother, she decided I must put on a pair of long pants,” says Pisar, now 82 and living in Paris. “She said, ‘In the long pants, maybe they will take you for a man and send you to forced labor.’ She didn’t say what would happen to her. I had to work that out later.”

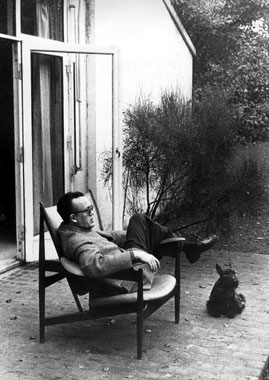

Samuel Pisar by Michelle BrackenOrphaned and alone in the death camps, Pisar survived through a kind of feral cunning. His life expectancy, he says, was only about two weeks; condemned to the gas chamber, he escaped by grabbing a bucket and convincing the guards he was just there to mop the floor.

Samuel Pisar by Michelle BrackenOrphaned and alone in the death camps, Pisar survived through a kind of feral cunning. His life expectancy, he says, was only about two weeks; condemned to the gas chamber, he escaped by grabbing a bucket and convincing the guards he was just there to mop the floor.

“Because I was so young and didn’t think as much as others, I was able to act as an instinctive animal,” he says. “To smell danger, and do something about it.”

He managed to escape from a Dachau death march at the end of the war and was rescued by American troops. Skeletal and barely alive, he was taken in by one of the regiments as a sort of “mascot,” he says, and survived in postwar Germany by scrounging coffee, cigarettes, and liquor and selling them on the black market. He was sixteen, living by his wits, and headed for serious trouble.

“There was anger in me,” he says. “I didn’t go to school. I didn’t even hold a book in my hand for six years. I could have become a terrorist, I suppose. I had good reason to: vengeance.”

Instead, he was given a chance at a new life. An aunt in Paris tracked him down and sent him to live with relatives in Australia, where he caught up on his missed education, eventually earning a law degree from the University of Melbourne.

That was just the beginning. Pisar went on to Harvard, where his doctoral thesis caught the eye of president-elect John F. Kennedy and led to a position on Kennedy’s Task Force on Foreign Economic Policy while he was still in his twenties. His work in Washington launched a career as one of the most influential analysts of East-West relations of the time. His 1970 book “Coexistence and Commerce” helped shape the Nixon Administration’s policies toward China and the Soviet Union, and Pisar himself became an advisor to many of the Fortune 100 companies — all while earning another doctorate from the Sorbonne, representing Hollywood celebrities from Elizabeth Taylor to Rita Hayworth, and being short-listed, in 1974, for the Nobel Peace Prize.

“Life,” says the Auschwitz survivor, “has been scandalously good to me.”

Through much of this period, Pisar was also forging a friendship with Bernstein that would last for decades. They met through Pisar’s wife, Judith, an accomplished musician who headed the American Center in Paris and had been director of music at the Brooklyn Academy. Judith turned the Pisar home in Paris (which once belonged to Claude Debussy) into a sort of salon; Arthur Rubinstein would drop by to play the piano, Seiji Ozawa stopped in when he was in town, and John Cage would come over for a game of chess.

But the dominant figure, says Pisar, was always Bernstein.

“It was a very special friendship,” Pisar says. “He asked me many questions about Auschwitz, and we would talk until 5 in the morning.”

The conversations affected Bernstein profoundly. “I don’t like to talk about the horrors,” says Pisar, “so I told him once, just to relax him, about the humor in the camps. There was even gambling; that piece of gray bread that your life depended on was the stake, and … well, can you imagine a farting competition? Some people, particularly the Russians, were virtuosos, and the guy who won took all the pieces of bread.

“When I told Lenny that story, he sobbed — sobbed,” remembers Pisar. “I thought I was telling him a mild story. But he, of course, understood the immense tragedy of it.”

As their friendship grew, the two worked together on a concert in Warsaw marking the 50th anniversary of the outbreak of WWII. But Bernstein had even bigger plans.

“He wanted to do a Holocaust opera,” says Pisar. “And I said, ‘Lenny, I don’t like the idea. I have strong nerves — but I don’t see Renata Tebaldi in front of a gas chamber, emoting with an aria.’”

Bernstein persisted, and in 1990, after reading Pisar’s memoir “Of Blood and Hope,” he asked him to write a text for Kaddish, instead. Bernstein had been trying to fix the narration for years and a shorter version emerged in 1977, but the composer remained unsatisfied. “It's still too much,” he told an interviewer, “and it's still too corny.”

Pisar turned Bernstein down, saying he wasn’t competent to undertake such a monumental task and unwilling, as he puts it, “to reopen my conflict with the Almighty.” The composer died a few months later, and Pisar put the request out of his mind. But after the attacks of September 11, 2001, he reconsidered.

“Suddenly I felt the world was becoming unstable again,” he says. “And I thought to myself, I have to do something.”

The result is an intimate, often harrowing journey into Pisar’s own childhood in the camps, leading to an angry confrontation with God and a hopeful reconciliation. He rails against the folly of man and the “deluge of hatred, violence and fear that is engulfing us again,” hoping, he says, to honor the memory of his fellow prisoners who died in the camps.

But most of all, he says, he wants to sound an alarm to a world that seems increasingly bent on its own destruction.

“What makes Kaddish relevant now is that the world has come to meet it,” says Pisar. “The world is inflamed again, by terrorism, by the mythology of death, by rampant economic disruptions.” Kaddish, he says, “is not only to cry about the past — but also to warn for the future.”

eighth blackbird at the Library of Congress

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • May 22, 2011

If you thought contemporary classical music was thorny, academic stuff — well, okay, a lot of it is. But there are plenty of serious composers writing exciting and accessible music as well, as the hip, young ensemble eighth blackbird proved on Friday night at the Library of Congress. The group had titled the program “Still Life,” but it was hard to find anything still or even slow-moving about it; this was some of the most kinetic, exuberant and purely pleasurable music to be found anywhere. The 30-year-old Missy Mazzoli is the current darling of the new-music world, and her mesmerizing “Still Life With Avalanche” showed why. Mazzoli writes pulse-driven music based on fairly simple materials but delights in pulling the rug out from under listeners with unexpected shifts of color and strange, elusive harmonies. “Still Life” was more delectable than powerful (think “Still Life With Snow Flurry”) but was still an involving and very moving work. Philippe Hurel’s 1996 piece “. . . a mesure,” though, was the genuine avalanche; a highly caffeinated virtuoso piece that may have contained more actual notes than the rest of the evening combined. Exhilarating, stunningly beautiful and brilliant in every sense, it’s a steamroller not to be missed.

The 30-year-old Missy Mazzoli is the current darling of the new-music world, and her mesmerizing “Still Life With Avalanche” showed why. Mazzoli writes pulse-driven music based on fairly simple materials but delights in pulling the rug out from under listeners with unexpected shifts of color and strange, elusive harmonies. “Still Life” was more delectable than powerful (think “Still Life With Snow Flurry”) but was still an involving and very moving work. Philippe Hurel’s 1996 piece “. . . a mesure,” though, was the genuine avalanche; a highly caffeinated virtuoso piece that may have contained more actual notes than the rest of the evening combined. Exhilarating, stunningly beautiful and brilliant in every sense, it’s a steamroller not to be missed.

Philip Glass wrote “Music in Similar Motion” in 1969, the heyday of minimalism, and the piece is pure Glass: repetitive and repetitive and repetitive. It was followed by the world premiere of Stephen Hartke’s “Netsuke,” six miniatures for violin and piano that, like the tiny carved Japanese figures that are their namesakes, were beautifully crafted, often grotesque, a bit arcane and not to every taste. But Hartke’s wit came out much more clearly in “Meanwhile: Incidental Music to Imaginary Puppet Plays,” a colorful work brought off with intelligence and style by the blackbirds, who played spectacularly throughout the evening.

In Copenhagen, A Renaissance for Finn Juhl

By Stephen Brookes • Modernism Magazine • Winter 2010

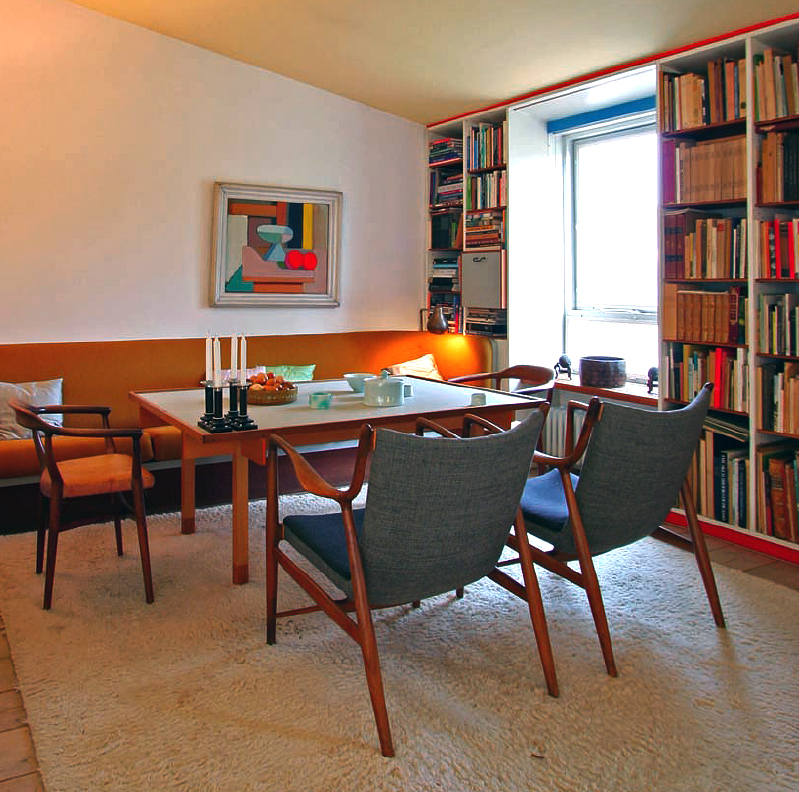

On the northern edge of Copenhagen, tucked away in a leafy, upscale neighborhood of old houses, old money and even older Lutheran values, sits a plain white house. At first glance, the place seems unremarkable, almost utilitarian; just two one-story buildings connected in an L-shape, opening onto a large garden. Simplicity, color and light reign in the main living area of Finn Juhl’s house. Photo by Anders Sune Berg

Simplicity, color and light reign in the main living area of Finn Juhl’s house. Photo by Anders Sune Berg

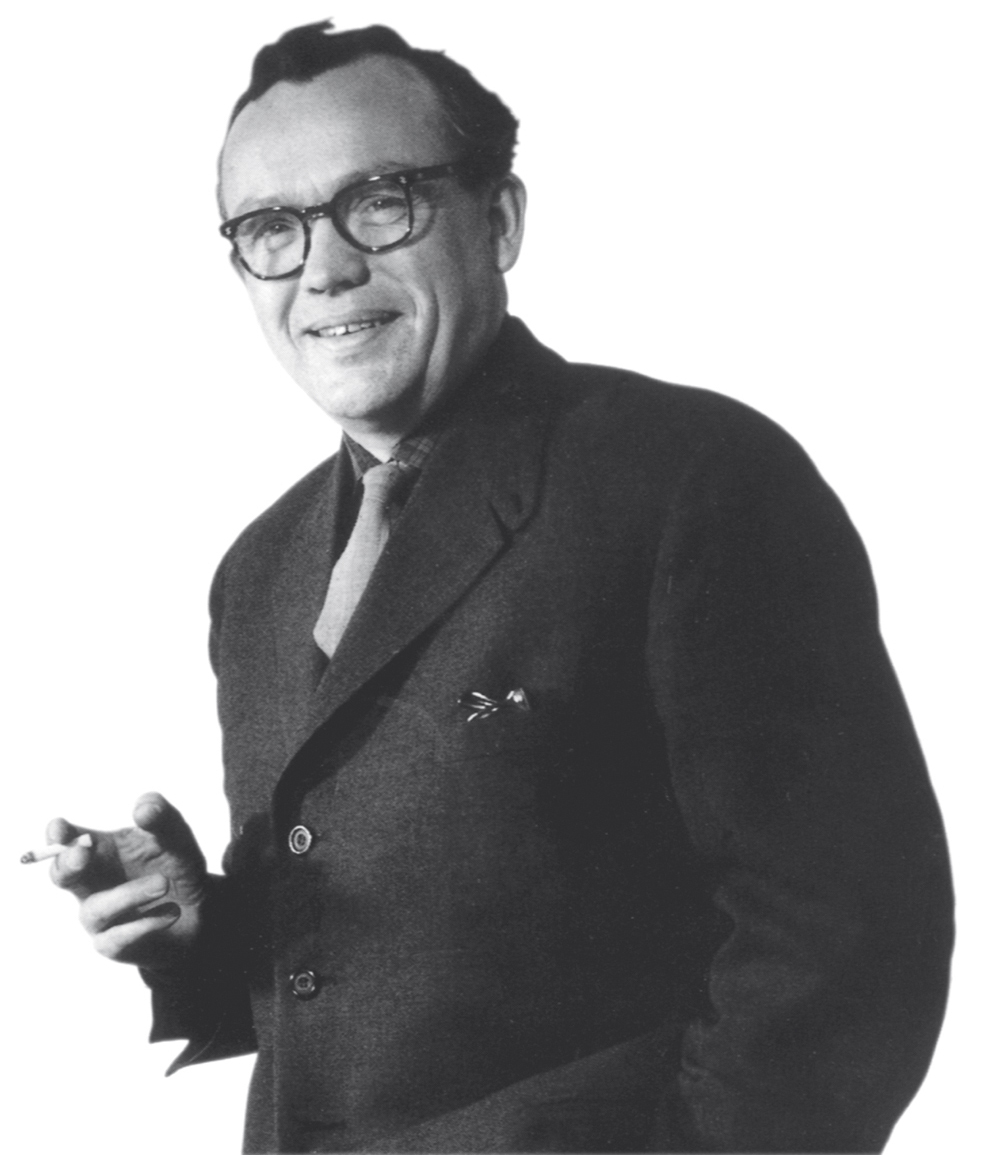

But step inside, and the house becomes anything but ordinary. The open, light-infused rooms are filled with some of the most provocative furniture of the 20th century, from a 1949 Chieftain chair with its imposing, shield-like back, to an iconic Poet couch that gently embraces you in its wings. Paintings from Danish midcentury artists float over chairs and tables formed with such organic lines that they seem almost alive. It’s a house where everything from the traditional Danish carpets to the canvas-colored ceiling comes together in a fresh and satisfying whole. For this is the house that Finn Juhl — the quiet and enigmatic architect who many regard as the father of Danish Modern — designed, built and lived in for more than 40 years. Finn Juhl“I’ve been here so many times, but I still find new details to discover,” says Birgit Lyngbye Pedersen, an art historian who bought and restored the house in 2007 and donated it to the Danish government as a museum, which opened in 2008. “Juhl thought about every detail. He had a vision of making everything for the house, even the cutlery. So the house is unique; it lets you see how Juhl thought about design in his own life, down to the smallest things.”

Finn Juhl“I’ve been here so many times, but I still find new details to discover,” says Birgit Lyngbye Pedersen, an art historian who bought and restored the house in 2007 and donated it to the Danish government as a museum, which opened in 2008. “Juhl thought about every detail. He had a vision of making everything for the house, even the cutlery. So the house is unique; it lets you see how Juhl thought about design in his own life, down to the smallest things.”

Finn Juhl was perhaps the most gifted of Denmark’s extraordinary crop of “Golden Age” designers, a group that came of age in the 1940s and ‘50s and included such luminaries as Arne Jacobsen, Hans Wegner and Børge Mogensen. But by the time he died in 1989, Juhl was virtually forgotten in his homeland — so neglected, in fact, that the Danish government showed little interest in preserving the house after Juhl’s longtime companion, Hanne Wilhelm Hansen, died in 2003. “They thought it was too simple,” says Lyngbye Pedersen. “They didn’t see the point. Most Danes didn’t know about Finn Juhl, and even the Design Museum didn’t collect his work!”

But all that is changing dramatically. With the opening of the house (now part of the Ordrupgaard Museum, which adjoins the property), interest in Juhl has been rising fast. On the international market, prices for the designer’s original pieces are reaching astronomical levels, interest among Asian collectors is almost fanatical and reissues of Juhl’s designs are selling out; the American retailer Design Within Reach began offering several pieces to the U.S. market this past summer. Meanwhile, the Danish Museum of Art and Design has assembled a fine Juhl collection, and one of the designer’s most important projects — the Trusteeship Council Chamber at the United Nations headquarters in New York — is being completely restored.

“Finn Juhl is having a renaissance around the world,” says Preben Pontoppidan, export director of the Danish furniture manufacturer Onecollection, which is licensed to produce Juhl’s designs. “And it’s long overdue.” Juhl’s life was, in fact, a roller coaster of fame and obscurity. Born in 1912, he trained as an architect but soon moved into interior design, where his gifts were quickly recognized. High-profile projects in the 1940’s and 50’s (including the Trusteeship Council Chamber, the Danish ambassador’s residence in Washington, DC and all of SAS Scandinavian Airlines’ air terminals in Europe and Asia) brought him international recognition, and he organized many of the exhibitions — including the “Good Design” exhibit in Chicago in 1951, and another at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1960 — that did much to popularize Danish mid-century design around the world.

Juhl’s life was, in fact, a roller coaster of fame and obscurity. Born in 1912, he trained as an architect but soon moved into interior design, where his gifts were quickly recognized. High-profile projects in the 1940’s and 50’s (including the Trusteeship Council Chamber, the Danish ambassador’s residence in Washington, DC and all of SAS Scandinavian Airlines’ air terminals in Europe and Asia) brought him international recognition, and he organized many of the exhibitions — including the “Good Design” exhibit in Chicago in 1951, and another at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1960 — that did much to popularize Danish mid-century design around the world.

His most important accomplishments, though, were to be in furniture — a field in which he had no training at all. Starting with pieces for his own apartment in the 1930’s, Juhl took a sculptural approach and quickly turned tradition on its head, playing with biomorphic shapes and drawing inspiration from surrealist painters such as Jean Arp and the art of primitive cultures. Teak fascinated him, and he quickly formed a partnership with the gifted cabinetmaker Niels Vodder; together they tested the limits of what the wood could be made to do.

His talent was immediately clear. One of his first designs was the now-iconic “Pelican” chair of 1939, whose swooping arms and exuberant curves anticipated the 1960’s by decades and still look fresh today. Other innovative pieces soon followed, including the delicately flowing NV-45 chair of 1945, the beguiling “Poet” couch from 1941, and perhaps the most imposing chair ever built, the throne-like “Chieftain” of 1949. Painstakingly hand-crafted and produced in miniscule quantities (no more than a dozen of the original Pelicans were made, and fewer than eighty of the Chieftains), they introduced structural innovations — such as “floating” seats and backs — that quickly became hallmarks of the Danish Modern vocabulary.

Juhl began winning awards at Copenhagen’s prestigious Cabinetmakers’ Guild exhibitions. But for all their brilliance, some critics found his designs too radical (one described the Pelican as a “tired walrus”), while many of his colleagues thought he was on the wrong esthetic — or perhaps political — path.

“Finn Juhl was different from the other designers of the time, and they didn’t like him,” says Lyngbye Pedersen, walking through the Juhl house on a sunny, cool morning last summer. “In postwar Denmark, there was a new form of living — the welfare state — and the designers made furniture they called ‘democratic.’ But Juhl was not part of that. His furniture was influenced by free art and prehistoric artifacts. It was not simple. It was hand made, it was expensive, and it was seen as elitist.”

The climate seemed more welcoming in America, and in the 1950’s Juhl shifted toward a more commercial, “common-man” approach, producing a line of mass-produced furniture for the Michigan-based Baker Furniture Inc, and even a refrigerator for General Electric. His fame spread when Edgar Kaufmann Jr., the design director of the Museum of Modern Art, took an interest in Juhl and enthusiastically promoted his work.

But by the 1970’s the Danish Modern wave had largely passed. Juhl fell into obscurity, financial difficulty and relative solitude. Work dried up; he had to lay off most of the employees in his design firm, and even sold pieces from his personal art collection to get by. A retrospective of his work at the Danish Museum of Art and Design in 1982 led to a brief revival of interest, but he never again attained the status he once enjoyed. Finn Juhl passed his last years quietly, dying in May 1989 at the age of seventy-seven.

The extraordinary legacy of Juhl’s life, though, lives on in his house. Built in 1942 with money from an inheritance and the simple materials available in wartime Denmark, it’s an early example of open plan layout. Gabled and deceptively plain from the outside, it was designed “from the inside out,” as Lyngbye Pedersen puts it, with clear sight lines from room to room and an airy, light-filled ambiance that makes the house seem much larger than it is. After buying the house, she restored it to the way it was when Juhl was alive, and the result is a fascinating mix of the designer’s most important furniture, numerous prototypes and blueprints, Asian artifacts, and his personal collection of paintings and sculpture by Scandinavian artists including Asger Jorn, Sonja Ferlov Mancoba and Erik Thommesen. Finn Juhl“Juhl was really about three things: furniture, color, and a piece of art,” Lyngbye Pedersen says. The main building, for instance, is arranged into several distinct but connected areas, with art and furniture defining each space. A Poet couch and a Chieftain chair form a sitting area around the traditional fireplace, presided over by a striking portrait of Hanne Wilhelm Hansen by the painter Vilhelm Lundstrom. Low tables display “still lifes” of pieces of sculpture and chinaware, and a pastel Scandinavian rug adds color and leads the eye deeper into the living space, past a 1951 table bench and a Chinese sculpture toward a table on a thick white rug.

Finn Juhl“Juhl was really about three things: furniture, color, and a piece of art,” Lyngbye Pedersen says. The main building, for instance, is arranged into several distinct but connected areas, with art and furniture defining each space. A Poet couch and a Chieftain chair form a sitting area around the traditional fireplace, presided over by a striking portrait of Hanne Wilhelm Hansen by the painter Vilhelm Lundstrom. Low tables display “still lifes” of pieces of sculpture and chinaware, and a pastel Scandinavian rug adds color and leads the eye deeper into the living space, past a 1951 table bench and a Chinese sculpture toward a table on a thick white rug.

This was Juhl’s preferred work space — a corner with an NV-46 chair, lit by a rear window, enclosed with bookcases full of art and architecture books in at least four different languages. But what’s most fascinating about the space is a corkboard covered with Juhl’s visual notes: blueprints for a country house, a poster of a chair exhibit, and an eclectic array of photos ranging from an Egyptian sarcophagus, to the ornate interior of a Renaissance room and the silhouette of an African fisherman.

Another sitting area includes two NV-45 chairs and a rare NV-44 around a table, offset by a 1938 still life by Lundstrom and a prototype lamp of Juhl’s own design. Overhead, tying all three areas together, is a pale yellow ceiling. “Juhl wanted the color to evoke light coming through the roof of a tent,” says Lyngbye Pedersen.

An entryway with a low-slung “Japan” chair (1958) connects the main house to the wing, up a short flight of stairs. The dining room contains a “Judas” table from 1949 (its teak surface is inlaid with 30 pieces of silver), surrounded by six of Juhl’s elegant “Egyptian” chairs from the same year. A short hallway leads to a bedroom simply furnished with a bed, an Ashanti stool and little else, while the master bedroom contains more Juhl gems, including a multicolored cabinet, an elegant shelf system filled with books, and an FJ-48 and bench sofa arranged around a table. The house is attracting growing numbers of visitors — and curiously, the majority are from Japan. “For some of the Japanese, it’s like going to church,” says Lyngebye Pedersen. “They become very quiet; some start crying.” The largest collection of Juhl in the world, in fact, belongs to a professor at Sapporo University named Noritsugu Oda, and other Japanese collectors regularly make pilgrimages to Copenhagen to shop for Juhl originals. And next year, even those who can’t make the trip won’t be left out: the Japanese company Kitani is even building a replica of Juhl’s house outside of Tokyo, exact to the tiniest detail.

The house is attracting growing numbers of visitors — and curiously, the majority are from Japan. “For some of the Japanese, it’s like going to church,” says Lyngebye Pedersen. “They become very quiet; some start crying.” The largest collection of Juhl in the world, in fact, belongs to a professor at Sapporo University named Noritsugu Oda, and other Japanese collectors regularly make pilgrimages to Copenhagen to shop for Juhl originals. And next year, even those who can’t make the trip won’t be left out: the Japanese company Kitani is even building a replica of Juhl’s house outside of Tokyo, exact to the tiniest detail.

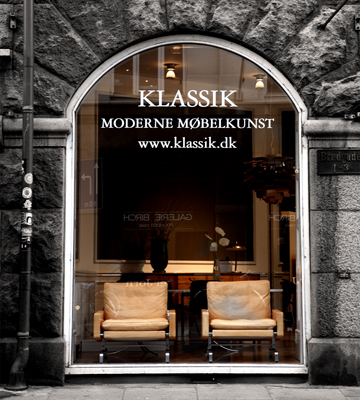

“Eighty percent of what we sell of Juhl goes to Japan, but South Korea and Taiwan are also becoming big markets,” says Per Poulsen, the manager of Klassik Moderne Mobelkunst, one of the premiere galleries in Copenhagen. And most of the buyers, he says, have little interest in Jacobsen, Wegner, or any of the other Danish Modern stars. “The people who buy Juhl,” he says, “are not interested in the other designers.”

The interest has pushed prices for Juhl’s work up by about ten percent a year over the past decade, says Poulsen, putting the rare, original pieces out of the range of many collectors. But many of the icons are being reissued, and it’s now possible to get many pieces — including the Pelican chair — for under $5,000.

With the 100th anniversary of Juhl’s birth approaching in 2012, many in Copenhagen are hoping that his work will finally get the recognition it deserves. That may or may not happen, they say, but at least Juhl is no longer fading from view in his own country.

“We honor Finn Juhl now,” says Lyngbye Pedersen, with a sigh. “It’s a pity we didn’t do it when he was alive.”

•••••••••••

VISITING THE JUHL HOUSE

Finn Juhl’s house is part of the Ordrupgaard art museum, and is open weekends and holidays, or by special arrangement; check the website for times. Admission is 90 Danish kroner (about $15). Ordrupgaard is located just over 8 km from the center of Copenhagen and is somewhat inconvenient to get to, but can be reached by train and bus; a car will give you flexibility to explore the surrounding area of Charlottenlund, where several Jacobsen houses are located.

WHERE TO STAY Copenhagen has any number of comfortable hotels, but lovers of Danish Modern may want to take a look at the historic, 260-room Radisson Blu Royal Hotel (Hammerichsgade 1) designed by Arne Jacobsen. The lobby features Jacobsen’s famous “Egg” and “Swan” chairs, but the hotel has been thoroughly updated — it’s very comfortable, but there’s not much mid-century flavor left. Ask if you can see room 606, though, which has been maintained exactly as Jacobsen designed it — except for the gigantic flat screen TV in the middle of the room. Aaarrrgh.

Copenhagen has any number of comfortable hotels, but lovers of Danish Modern may want to take a look at the historic, 260-room Radisson Blu Royal Hotel (Hammerichsgade 1) designed by Arne Jacobsen. The lobby features Jacobsen’s famous “Egg” and “Swan” chairs, but the hotel has been thoroughly updated — it’s very comfortable, but there’s not much mid-century flavor left. Ask if you can see room 606, though, which has been maintained exactly as Jacobsen designed it — except for the gigantic flat screen TV in the middle of the room. Aaarrrgh.

Just as central and infinitely more interesting is the wonderful Hotel Alexandra (H.C. Andersens Boulevard 8), each of whose rooms is decorated with the furniture of a different designer, including Hans Wegner, Borge Mogensen and of course Finn Juhl. The hotel’s owners are passionate about the period, and the Alexandra is a treasure trove of mid-century gems. Not to be missed — at the very least, stop in and admire the lobby.

WHERE TO BUY For upscale art and furniture galleries in Copenhagen, head to Bredgade Street, where you’ll also find the Danish Museum of Art and Design, which has a fine collection of (mostly) chairs from the great designers. When you’re ready to buy, stop in at the friendly, low-key Klassik Moderne Mobelkunst (Bredgade 3), one of the premiere galleries in town for vintage midcentury furniture. Or head over to the funky neighborhood of Nørrebro and explore its many antique shops, where bargains can sometimes be found. One of the best galleries there is Roxy Klassik (Fælledvej 4), which has a vast and fascinating collection of Danish Modern. Fine examples of contemporary design can also be found at Illums Bolighus (Amagertorv 10) and the gift shop of the Dansk Design Center (HC Andersens Boulevard 27).

For upscale art and furniture galleries in Copenhagen, head to Bredgade Street, where you’ll also find the Danish Museum of Art and Design, which has a fine collection of (mostly) chairs from the great designers. When you’re ready to buy, stop in at the friendly, low-key Klassik Moderne Mobelkunst (Bredgade 3), one of the premiere galleries in town for vintage midcentury furniture. Or head over to the funky neighborhood of Nørrebro and explore its many antique shops, where bargains can sometimes be found. One of the best galleries there is Roxy Klassik (Fælledvej 4), which has a vast and fascinating collection of Danish Modern. Fine examples of contemporary design can also be found at Illums Bolighus (Amagertorv 10) and the gift shop of the Dansk Design Center (HC Andersens Boulevard 27).