Orchestra Baobab at Lisner

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • June 21, 2008

_________________________________________________________________________

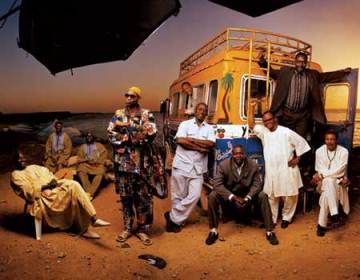

Photo by Jonas KarrssonThe Birchmere booked Orchestra Baobab into its spacious, no-seats dance hall on Thursday night, rather than the usual stage-and-tables performing space. Good thing -- it's impossible to sit still when this Senegalese band gets moving, and it gets moving fast. Churning out a set of Afro-Cuban dance pop (a style the group virtually invented back in the 1970s) it kept the crowd jumping all night, from the loose, sultry rhythms of "Nijaay" (off its newest album, "Made in Dakar") to the explosiveness of "Bul Ma Miin."

Lead singer Medoune Diallo was in fine form, leading the nine-piece band through its famously eclectic range of styles, which includes calypso, Congolese rumba and even American blues. Despite an ill-fated effort at a singalong (and really, how many people can sing in Wolof?), Diallo had the crowd with him from the opening notes of "Ndiaga Niaw" and held it to the end.

But he may have been upstaged by tenor saxophonist Issa Cissoko, who appears to be the happiest man on the planet. Smiling, dancing and firing off riffs in tunes like "Colette" and "Ndongo Dara," Cissoko looked like there was nowhere else he'd rather be, and the effect was infectious. Even guitarist Barthélemy Attisso -- whose low-key demeanor belies a ferocious musical brain -- couldn't help but crack a smile.

Attisso's playing, in fact, was almost reason enough to see the show. The Orchestra Baobab's strength comes from its feel-good, imaginative music rather than the virtuosity of its players; there isn't a lot of showing off onstage. But Attisso's a fascinating musical thinker, as he proved again and again -- particularly on the irresistible, Cuban-flavored "Jiin Ma Jiin Ma."

Salif Keita: From Outcast to Icon

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • June 15, 2008

___________________________________________________________________________________

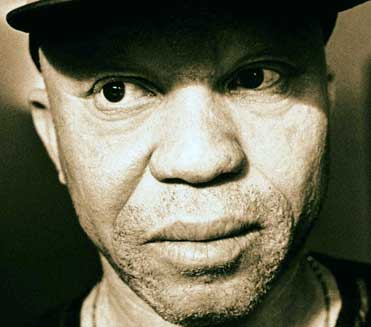

Salif KeitaThe horrific reports started streaming in from East Africa last year -- first in a trickle, then in a flood.

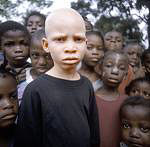

In Tanzania, a teacher was arrested for killing his own son, because the child had been born an albino. In an area around Lake Victoria, the corpse of another albino was found with all its limbs cut off; others turned up minus tongues or genitals, and earlier six albinos were killed for their skins, which were then displayed for sale. By some accounts, as many as 50 albinos in Tanzania alone have been killed in the past year -- their blood, hair and flesh destined for the magic potions of witch doctors.

“People kill albinos and chop their body parts, including fingers, believing they can get rich," Tanzania’s president Jakaya Kikwete said in a television address earlier this year. The fault, added Provincial Commissioner Luteni Kanali Issa, lay with witch doctors from all across Africa. “The influx of these traditional healers has contributed to mass deaths of albinos,” he said. “And soon they will be wiped out."

The reports are shocking, but they don’t surprise Salif Keita.

“This sort of thing has been happening for a long time, and it’s still going on,” says the Malian singer, speaking by phone from his home in Djoliba, near the capital of Bamako. “People do not understand about albinos – there are so many superstitions about them, because people are not educated.”

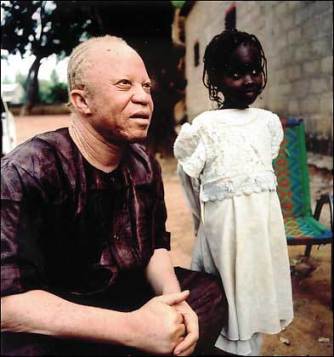

Keita should know – he’s an albino himself. At 58, the Afropop superstar (who appears at Lisner Auditorium this Friday) has become one of the most celebrated African musicians in the world, with a string of international hits. Now he’s using his considerable fame to change how albinos are treated in Africa, and to fight against the deep-rooted superstitions that can lead – as in the recent episodes in Tanzania – as far as murder.

Like most African albinos, Keita has been a social outcast virtually since the day he was born. The scion of a royal family (he’s a direct descendent of Sundiata Keita, the Mandinka warrior king who founded the Malian empire about 1240), Keita’s pink complexion and yellow hair shocked his father, who shunned him in his early years. His fragile skin meant he couldn’t work in the fields, and discrimination thwarted his ambition to become a teacher.

With few other options, he began to sing in the streets as a sort of modern-day griot, or wandering musician – a very low-caste occupation.

“In my family, it was not very easy to be a musician,” he says. “My family is the royal family, and the royal family makes war – they don’t sing.” But Keita’s albinism turned into a blessing. His songwriting talent and luminous, unmistakable tenor voice -- he’s widely known as “the Golden Voice of Africa -- began to attract notice, and he was recruited by a state-sponsored group called the Rail Band in 1970. Moving on a few years later to a band called Les Ambassadeurs, he began incorporating Malian influences into the Afro-Cuban music the band played.

But Keita’s albinism turned into a blessing. His songwriting talent and luminous, unmistakable tenor voice -- he’s widely known as “the Golden Voice of Africa -- began to attract notice, and he was recruited by a state-sponsored group called the Rail Band in 1970. Moving on a few years later to a band called Les Ambassadeurs, he began incorporating Malian influences into the Afro-Cuban music the band played.

The music caught on, and Keita’s fame began to spread. In 1977 he was awarded the National Order of Guinea by President Ahmed Sekou Toure, and in response he wrote the hugely successful song “Mandjou”, which tells the story of the Malian people. But political unrest was growing in Mali, and (as an outspoken critic of the government) he left the country, resettling in Paris in 1984.

And there things began to take off. Blending the traditional griot music of his childhood with influences from Guinea, the Ivory Coast and Senegal, as well as the music of Cuba and Portugal, Keita almost single-handedly launched the Afropop movement with the pioneering 1987 album “Soro.” Restless and inventive, he went on to release the jazz-influenced “Amen” (1991) and the more rock-oriented “Papa” in 1999, moving to a more acoustic and traditional sound with “Moffou” (2002) and the 2006 release, “M’Bemba” – winning six Grammy nominations along the way.

As his success grew, Keita was becoming increasingly concerned with the situation of Africa’s albinos. Albinism is an inherited genetic condition in which melanin – crucial to protecting the skin – is missing, causing pale complexion, light hair and vision problems. In the West, it’s not particularly common or noticeable (roughly 1 in 20,000 people have it in the US), but in some parts of Africa it affects as many as 1 in 1,100 people. And because it’s caused by a recessive gene (which can skip generations), an albino child can be born to black parents, causing confusion, suspicions of infidelity, and fears that the child is cursed.

“The biggest thing that people with albinism face is that they generally look different, particularly in cultures of color,” says Mike McGowan, director of the US-based National Organization for Albinism and Hypopigmentation. “And there’s an unfortunate part of human nature that shuns difference.”

With their pinkish skin and yellowish hair, Africa’s albinos stand out dramatically; they’re called derogatory names -- “ghosts” and “peeled potatoes” are some of the gentler ones -- and a range of bizarre myths have grown up around them. They’re often thought to have magical powers; some cultures, for instance, think albinos just vanish rather than actually die. Many of the superstitions are harmless, like the one that says drinking Fanta orange soda can lead to the conception of an albino baby. But others are more insidious: A recent rise in rapes of albino women is being attributed to a belief that sex with an albino can cure HIV-AIDS. While the social discrimination is often fierce, the main problem most African albinos face is simply staying alive. Since their skins lack protection against the brutal sun, skin cancer is a constant threat, with treatment expensive and often unavailable. Poor eyesight keeps many from finishing school, leading to perceptions that they are weak or mentally deficient.

While the social discrimination is often fierce, the main problem most African albinos face is simply staying alive. Since their skins lack protection against the brutal sun, skin cancer is a constant threat, with treatment expensive and often unavailable. Poor eyesight keeps many from finishing school, leading to perceptions that they are weak or mentally deficient.

So in 1991, Keita helped to found a foundation called SOS Albinos, in Bamako, and returned permanently to Mali in 2004 to devote more time to the cause. He’s distributed glasses and thousands of tubes of free sunscreen to Mali’s albinos (one of the most practical steps to improve their condition), established a hospital for victims of skin cancer, and worked to help integrate them into society though education.

“They need help,” says Keita. “Many of their problems come from the sun, because many of them are farmers, and they get skin cancer. First, we gave them sunscreen, and then we built a hospital, because no one wanted to help them. But now we have people who will take care of them.”

Keita plans to expand his campaign across Africa, and recently launched the Salif Keita Global Foundation [www.salifkeita.org] to raise money for free healthcare and educational services. There are a few other support groups across the continent, including Tanzania’s Albino Society, the Albino Association of Zimbabwe and the Albino Association of Malawi, but they are marginally funded at best; few outside observers see any dramatic improvement coming in the lives of most albinos.

"Beyond finding the albinism gene, there's precious little research being done" to understand the condition or prevent new cases, says NOAH's McGowan.

But Keita remains optimistic.

“One day, there will be no more albinos. We’ll find a solution for it, so that when you’re born, you’re normal,” he says. “We will find a solution – I’m sure.”

Kids and Modern Art: Think Outside the Frame

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • Wednesday June 11, 2008

_______________________________________________________________________

We try to be good parents. Really, we do! We’ve worn our brain cells to little nubs giving our two daughters a grounding in the arts. Piano lessons? Check. The National Gallery? Check. Dance classes, art camp, concerts at the Kennedy Center? Check, check, check again. Sure, threats may have been employed, and possibly a little light bribery from time to time. If that’s what it takes to nurture young aesthetes in a YouTube world, so be it.

But there was one important area we’d always neglected – the world of contemporary art.

Photo by Mario Tama/Getty ImagesSo with spring break upon us, we got a brilliant idea. Instead of the usual fun, relaxing week on a Florida beach, we’d head to New York for a cultural vacation. It would be great -- four days of intensive immersion in modern art, going to galleries and exploring the Guggenheim, the Whitney Museum of American Art and, of course, the mother ship: The Museum of Modern Art.

We probably wouldn’t get very tan. But we’d come home with our brains tingling, bonding as a family over lively discussions of the latest ideas in avant-garde art.

Ok, fellow parents – stop laughing.

No matter how admirable the intention, art vacations with kids can be fraught with peril, as we discovered a few weeks later on New York’s Upper East Side, pushing our way through the crowded lobby of the Whitney Museum.

The Whitney seemed like a perfect place to start, since it happened to be hosting the famous Whitney Biennial -- a major survey of new work by the country’s most cutting-edge artists. It promised to define “where American art stands today.” What better introduction could there be?

But it looked like a pretty advanced show, so I gave the girls a “Modern Art 101” pep talk over dinner the night before.

“A lot of what we’ll see may seem weird,” I told them. “But give it a chance, even if you don’t get it right away. It’s going to be fun! Artists are basically playful – they’re playing with ideas, turning things on their head, creating surprising, beautiful stuff designed to make you think in new ways. So let’s go with an open mind. It’s going to be an adventure.”

But now, standing in the Whitney and staring into Jason Rhoades’ “The Grand Machine / THEAREOLA,” I wasn’t so sure. The piece consists of a huge room filled with -- not to get overly technical about it – junk. Really: a shambles of old office chairs, candy wrappers and other trash strewn across the floor.

Charles Long's sculptures, modeled on bird droppingsChristina, the eldest, raised a teenaged eyebrow at me. “So -- is this ‘art’?” she said, making little quote marks with her fingers.

At a loss for words, I turned to the catalog for help. Rhoades’ work, it explained, tried to “obscure any clear artist intention by overloading the viewer with information and multivalent imagery.”

Righty-o. “Let’s go upstairs and see what else there is,” I said brightly.

But as we toured the exhibit over the next two hours, my little “art is fun” speech was looking increasingly out of touch. Room after room was filled with rough, in-your-face constructions of 2x4’s, broken glass and chunks of concrete. We picked our way around Jedediah Caesar’s blocks of resin-encased garbage, and skipped quickly past Charles Long’s spindly sculptures made of street trash and modeled – not kidding -- on bird droppings. We peered at Mitzy Pederson’s pile of cinder blocks and Ry Rocklen’s abandoned box spring, pondered a rough-hewn, Gatorade-powered “ecosystem” by Phoebe Washburn, and puzzled over Heather Rowe’s “Entrance (for some sites in dispute),” which looked like a demented delivery from Home Depot.

I looked at the girls. They were being good sports. But expressions of wonder and delight weren’t exactly dancing across their young faces.

“Not going well,” I whispered to my wife.

“No,” she whispered back. “Let’s go for cannolis.”

Now, the trip could have ended there in bitter defeat, with the girls scarred for life and unwilling to risk anything more edgy than a haystack or two by Monet. But after a day of regrouping – i.e. clothes shopping, a rock show at The Town Hall, and more than one cannoli -- we tried again.

And his time we did it right. Instead of isolating ourselves for hours in a museum grappling with Big Serious Issues, we explored the art scene lightly, as part of the city’s life. We strolled the streets of Soho and Chelsea, spending as much time eating ice cream and talking with people as going into galleries. We glided down the spiral ramp of the Guggenheim to take in the sculptures of Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang, then headed for a romp in Central Park. We stopped in at Walter de Maria’s serene “New York Earth Room” (an elegant Soho gallery that, for the past thirty years, has been filled to a depth of two feet with carefully groomed dirt) and, feeling oddly refreshed, ambled down Mercer Street to try on shoes.

And it turned out to be a great approach to exploring the city. There’s exciting new work in almost every corner of Manhattan – more than a hundred galleries in Soho and Chelsea alone, with exhibits opening every week -- and museums for every taste, from folk art to ultra-contemporary. In fact, you’ll run into art just strolling around, since the city is full of public sculpture like Isamu Noguchi’s “Cube” (at 140 Broadway) and Robert Indiana’s LOVE sculpture (corner of 6th Avenue and 55th Street) are usually a hit with kids.

There’s so much diversity, in fact, that you’re bound to stumble across something really extraordinary. For us, that happened on our last day, when we finally got around to the Museum of Modern Art. The MoMA’s an enormous place, where a serious art-lover could happily wander for days. But we skipped past the famous Cézannes and Matisses and elevatored directly to the top floor, where a new show called “Design and the Elastic Mind” had just opened.

Philip Worthington's "Shadow Monsters" at MoMAAnd suddenly, we were in the playground of the imagination we’d been looking for. On the walls, ghostly computer-generated “light weeds” swayed to virtual winds, while a huge Mylar manta ray swam in the air overhead. A meticulously crafted honeycomb vase, made entirely by bees to human instructions, glowed in a glass case. There were sculptures that responded to the life around them, outlandish chairs “grown” by mimicking human biology, maps of the world that constantly changed shape as data flowed in from around the planet.

On and on it went, each piece more wonderful and thought provoking than the last. The girls ran excitedly from room to room, and we finally caught up with them in Philip Worthington’s installation, “Shadow Monsters.” It’s an amazing piece that projects peoples’ silhouettes against a wall, transforming them in real time into hysterically funny new creatures, and the girls were dancing and laughing as they watched themselves sprout wings, horns and long, bouncing antennae.

I looked at my wife and grinned. Contemporary art, it seemed, had won a couple of new converts. We’d be back.

•••••

Survival Guide: Ten Tips for Introducing Your Kids to Art

Seeing modern art with kids can be daunting – but if done well, tremendously exciting. It’s always interesting to see what kids respond to, and while you don’t need to visit three museums in three days, as we did, a trip to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) can be a high point of any trip to New York. To make the most of the experience, follow these ten tips:

1. Know when to go. Try for a weekday when museums are less crowded. Many are closed Mondays or Tuesdays, but schedules vary. Check their websites for concerts, movies and special events, which can add interest to a visit. If the entry fees are daunting, take advantage of MoMA’s free admission on Fridays (when many of the museums stay open late) from 4-8 pm. The Whitney also offers pay-what-you-wish admission on Fridays from 6 to 9 pm, and the Guggenheim has a similar policy on Fridays from 5:45-7:45 pm. Free isn’t entirely free, though: you’ll be fighting big crowds.

2. Do your homework. It’s always good to know what you’re looking at, and while museum websites are helpful, Googling reviews of current exhibits will give you more insight. Talk with your kids about the exhibits and proper museum etiquette (no chewing on the art), and pick shows that they’re likely to respond to. For instance, we skipped “Tlatelolco and the localized negotiation of future imaginaries” at the New Museums of Contemporary Art. Just not cerebral enough.

3. Check out special programs for kids and families. MoMA has a number of events for kids 4 and up, and younger children may enjoy the interactive website “Destination: Modern Art”. The Whitney has “Family Fun Art Workshops” (ages 5-10), “Whitney Wees” (ages 4-5) and “Looking to Learn” tours for families most Saturday mornings; register by calling 212 671-5300.

4. Plan activities. Older kids will probably want to explore on their own, but smaller kids often like to be focused on specific tasks. Try “visual scavenger hunts,” remembering that questions like “point out paintings that are mostly blue,” will work better than “find a post-modernist commentary on anomie.” Sketching in a museum is a good way to focus on the art, but parents are asked to carry the pencils when not in use (pens and crayons are not allowed).

5. Skip the line. Nothing kills a museum buzz like standing in line, and there are often lines, especially in the morning. Buy tickets online at least a day ahead, and you can breeze right in. Feels great!

6. Feed the beast. A child marches on its stomach (as Napoleon would have said if he’d been a dad instead of Emperor), so keep the little treasures fed. Outside food is not allowed, but all the big museums have fun, comfortable restaurants. MoMA offers a kids menu at Café 2 on the second floor, and we had a light, delicious lunch at Terrace 5 upstairs. The Guggenheim has its Museum Café, and the Whitney hosts Sarabeth’s Restaurant -- both are pleasant places to break up your visit, but be prepared for lines.

7. Make gravity your friend. Try not to visit at the end of a long walking day: museums are tough on the feet. At the Guggenheim, take the elevator to the top and glide your way down the gently sloping spiral – otherwise you’re fighting gravity the whole way. And be sure to check as much of your gear as possible when you arrive.

8. Try gallery tours. These are often the best way to see a museum. The Whitney offers several free, docent-led tours of the museum every afternoon, and many others, including MoMA and the Guggenheim, have free audio self-guided tours; pick up a player at the entrance. MoMA has special audio tours for kids, teenagers and families, and you can download them in advance here. Or if you prefer the human touch, arrange to have a private family guided tour (call 212 708-9685).

9. Pace yourself. One museum a day is plenty for most kids, and it’s wise to limit your visit to about ninety minutes. Take breaks – many of the museums have sculpture gardens, which are perfect for this.

10. Plan a post-museum reward. It’s good to have something to look forward to, so promise kids ice cream, shopping, or a new puppy. Ok, maybe not the puppy. But MoMA has a world-famous gift shop with more than just the usual museum posters, and is well worth a visit. For ice cream, there’s the famous Serendipity on the Upper East Side (225 E. 60th, between 2nd and 3rd), which kids may recognize from the movie One Fine Day.

McFerrin Leads "World of Voices" at Kennedy Center

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • June 3, 2008

_____________________________________________________________________

Bobby McFerrinThe Kennedy Center's ongoing festival of a cappella music is virtually a summit of the world's top voice-only ensembles, performing everything from show tunes to Renaissance madrigals. The concerts this past week at the Millennium Stage have been both free and revelatory (and try arguing with that) but the best may have been reserved for Sunday night, when a global who's who of a cappella, hosted by the pioneering vocalist Bobby McFerrin, pulled out all the stops for a concert titled "A World of Voices."

McFerrin, of course, has done more to build interest in a cappella music than any other single performer, and it was quickly obvious why. An utterly natural musician with an irrepressible sense of play, he took a chair and began improvising an African-inflected tune in a high, gentle voice. Adding percussion by beating on his chest, he worked in deep bass notes, the sounds eerily imitating a thumb piano, then a lower vocal line, until he'd transformed himself into a virtual quartet -- a virtuosic and absolutely riveting performance that brought the house down.

McFerrin hosted the rest of the concert lightly, always singing rather than speaking, and drawing the audience into the performance with a deft comic touch. And the music flowed with astonishing diversity and depth, from the Czech girls choir Jitro -- whose fresh-faced singers (dressed in traditional costume and looking impossibly wholesome) sang a playful work called “Gorale” (Hillbillies) that ended in light fisticuffs -- to the Mexican ensemble La Capilla Virreinal de la Nueva España, who brought a gorgeous, rarely-heard selection of Mexican and Latin American music from the 16th and 17th centuries.

But it was the more famous names that stole the show. Chanticleer -- the reigning gods of the men's chorus world -- roam across the centuries with elegant nonchalance, and after opening with some early polyphony from Andrea Gabrieli, delivered a soaring, intense account of Mahler's "Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen," swanned though the Gershwin standard "Love Walked In" and topped things off with a stirring gospel number.

D.C.'s own Sweet Honey in the Rock delivered its self-described "intense social commentary" with several colorful songs, and the South African group Ladysmith Black Mambazo turned in gentle, enveloping harmonies drawn from traditional Zulu music, livened up with high kicks and much leaping around. The most amazing singing of the evening, though, came from Le Mystere des Voix Bulgares, whose strange, flavorful timbres and unearthly harmonies -- drawn from Bulgarian folk music -- sound both ancient and completely modern.

McFerrin closed the evening by bringing all the performers onstage for a collective improvisation, a statement, if one were needed, of the universality of music and the power of the human voice.

Lord of the Rings at Wolf Trap

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • May 23, 2008

______________________________________________________________________

There's probably never been as ambitious a film score as Howard Shore's 10-hour epic for the "Lord of the Rings" series. While it's not quite a Wagnerian-scale "Ring," the music is rich and complex, drawing on a vast range of styles and exotic instruments to evoke J.R.R. Tolkien's world of elves, hobbits and warlocks. But it's more than just background music: Shore uses an elaborate leitmotif technique (where musical themes are associated with specific characters or ideas, and are developed across the entire series) to hold the sprawling tale together. Lush, beautiful and full of intriguing surprises, it's no wonder that it's become one of the most popular film scores ever written.

There's probably never been as ambitious a film score as Howard Shore's 10-hour epic for the "Lord of the Rings" series. While it's not quite a Wagnerian-scale "Ring," the music is rich and complex, drawing on a vast range of styles and exotic instruments to evoke J.R.R. Tolkien's world of elves, hobbits and warlocks. But it's more than just background music: Shore uses an elaborate leitmotif technique (where musical themes are associated with specific characters or ideas, and are developed across the entire series) to hold the sprawling tale together. Lush, beautiful and full of intriguing surprises, it's no wonder that it's become one of the most popular film scores ever written.

So it was worth it to brave the teeth-chattering temperatures on Wednesday night and head out to Wolf Trap to see "The Fellowship of the Ring" (the first film in the series) projected on huge overhead screens while the Filene Center Orchestra, the City Choir of Washington and the World Children's Choir performed the score live.

Technically, it came off brilliantly; unlike the muddy presentation of "The Wizard of Oz" two years ago, "Fellowship" was clear and detailed, with well-balanced sound and an orchestra that sounded extremely natural despite being amplified.

And for this listener, anyway, it was like seeing the film for the first time. "Lord of the Rings" is a full-blown epic by anyone's standards, and needs to be experienced on as gigantic a scale as possible; one orchestra seems barely enough. And putting the music front and center gives the film a driving bolt of narrative power (which, frankly, it badly needs) and provides depth to the special effects that crash relentlessly across the screen.

Conductor Ludwig Wicki did a superb job of coordinating his enormous forces, and the choruses -- who had to sing in Tolkien-ish languages like Quenya and Sindarin -- performed with precision and style.

Great Noise Ensemble at the National Gallery

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post• May 20, 2008

____________________________________________________________________________

How can you not love a music group so cheerfully unstuffy that it calls itself Great Noise Ensemble? Composer/conductor Armando Bayolo put the band together a few years ago from young musicians gathered via Craigslist, and since then has been waging a crusade to "fight for the performance of new American music" in the D.C. area.

How can you not love a music group so cheerfully unstuffy that it calls itself Great Noise Ensemble? Composer/conductor Armando Bayolo put the band together a few years ago from young musicians gathered via Craigslist, and since then has been waging a crusade to "fight for the performance of new American music" in the D.C. area.

And to judge by Sunday's well-attended performance at the National Gallery of Art, the fight is going pretty well. The evening opened with Barbara White's "Learning to See," six spare and precisely calibrated miniatures inspired by artists. Often lovely and atmospheric, they were almost too ephemeral to make an impact and received a tepid audience response. But Evan Chambers's melancholy "Rothko-Tobey Continuum" for violin and tape was a dark, gripping gem, played with an elegant sense of restrained yearning by Heather Figi.

Blair Goins's "Quintet" abounded in lighthearted melodies and would have felt at home in the Paris of 50 years ago, though the odd instrumentation -- a tangled collision between a wind quintet and a string quintet -- led to some mushy sonorities and undercut its charm. More successful (and substantial) was Bayolo's own "Chamber Symphony." Full of lush ideas and a kind of fierce grandeur, it unfolded with subtle, driving power -- a work worth hearing again.

But the high point of the evening was the world premiere of Andrew Rudin's Concerto for Piano and Small Orchestra. Rudin has a gift for the kind of gesture that grabs you by the ears and won't let go, the music building in power as its inherent possibilities unfold. Extroverted, engaging and driven by an almost heroic sense of drama, it received a bravura performance from pianist Marcantonio Barone.

Antares play Bartók, Messiaen at Strathmore

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • May 17, 2008

____________________________________________________________________________

Olivier MessiaenRarely has a piece of music had a more dramatic birth than Olivier Messiaen's "Quartet for the End of Time." Written in 1941 while the composer was interned in a Nazi prison camp, it's a work of often confounding vision and spirituality -- an attempt (as Messiaen has described it) to enter musically into eternity. Not every ensemble is up to that daunting challenge, but Thursday night at the Mansion at Strathmore, the immensely talented quartet Antares made the work the centerpiece of its program -- and brought it off brilliantly.

The evening started with a reading of Ravel's "Mother Goose" suite, though, which to these ears felt disconcertingly down to earth. Written originally for the children of a friend, the suite is a playful, chimerical thing, drawn in delicate colors and populated with elves, fairies and other exotica. Its magic depends on its lightness, and the robust approach taken by the Antares players (Eric Huebner at the piano, Rebecca Patterson on cello, and clarinetist Garrick Zoeter and violinist Jesse Mills) didn't always show the music to its most gossamer advantage.

Bela Bartók

Bela Bartók's "Contrasts," by comparison, is about as gossamer as a punch in the face, and received a spectacular -- repeat, spectacular -- performance. Exploding out of the gate, it took off on a wild ride through Hungarian dance forms so exhilarating and propulsive that the players -- Mills and Zoeter, in particular -- looked as if they were about to spontaneously combust.

Flames averted, the ensemble returned for an account of the Messiaen quartet that was no less memorable. Antares has made a specialty of this work, and its absolute commitment was evident throughout; this was an utterly commanding performance, technically superb and radiant with otherworldly majesty. All played with exceptional insight; cellist Patterson gave a stunning account of the movement "Praise to the Eternity of Jesus," while Mills played the final movement as if he'd just received it from some distant, vast and magnificent reach of the cosmos.