At the Austrian Embassy, Cage Triumphs

By Stephen Brookes

The Washington Post September 29, 2007

A half-century after his death, Arnold Schoenberg's ghost still haunts most modern composers. But his legacy is complex -- and in a brilliant concert at the Austrian Embassy on Wednesday night, violinist Alexander Gheorghiu and pianist Florian Mueller showed how the father of 12-tone music has been affirmed, repudiated and finally transcended by the composers who came in his wake.

John CageThe program got off to an explosive start with Schoenberg's "Fantasie," Op. 47. Angular and angry, it's eight minutes of everything that's most hated about modern music. But it was followed by gentler works from his disciples. Anton Webern's spare, delicate Four Pieces, Op.7, were played with impeccable musicianship and grace, and the "Deux eclats" by Friedrich Cerha were beautifully played, full of quirky pizzicato effects and the occasional elbow-to-the-keyboard crash.

Then the repudiation. John Adams famously parodied Schoenberg in his Chamber Symphony and "Harmonielehre" -- pieces far more interesting, unfortunately, than his three-part "Road Movies" on this program. Made up of a minimalist hoedown, some existential brooding and a dense perpetuum mobile, they thumbed their nose at Schoenberg without actually saying all that much.

And finally, there was transcendence. Schoenberg once dismissed John Cage as "not a composer," but as Muller showed in a spectacular performance of the 1958 "Concert" for Piano and Orchestra -- with its extraordinary sonic beauty and intricate nuances -- Cage could echo the older composer while leaving him in the dust. And Cage's "two6" for violin and piano, which closed the program, was so profoundly delicate and ethereal that it seemed to radiate from another world.

In Conversation: Jefferson Friedman

By Stephen Brookes

The Washington Post September 30, 2007

(Note: this is a longer version of an interview with Jefferson Friedman that ran in The Washington Post on Sunday. For that version, please click here.)

Jefferson Friedman

When an aging janitor and onetime mental patient named Henry Darger moved out of his Chicago boardinghouse in 1971, his landlord discovered a bizarre legacy -- a 15,000-page novel and hundreds of paintings, all depicting a war on a distant planet between children and a regime that enslaves, tortures and kills them.

The novel -- titled The story of the Vivian Girls, in what is Known as the Realms of the Unreal – is a sprawling, often violent work. But it’s Darger’s paintings that have attracted the most attention, both for their bizarre subject matter and naïve, unschooled beauty, and he’s widely recognized as an important American artist. Thursday through Saturday at the Kennedy Center, the National Symphony Orchestra will be performing an orchestral work based on one of Darger’s most intense paintings, a diptych entitled “Sacred Heart: Explosion.”

We talked with composer Jefferson Friedman, 32, about his new work (which is part of a trilogy based on “outsider” artists titled "In the Realms of the Unreal") and his thoughts on one of the 20th Century’s most controversial painters.

Darger spent his life alone, in poverty, dealing with some pretty frightening personal demons. What drew you to him?

I think that most people who create, whether they're "outsider" or not, are trying to grapple with their inner demons. When I'm composing, I'm trying to get something from the inside to the outside. With Darger, it's just a more extreme case.

Sure -- but a lot of his art is seriously disturbing: a group of little girls who get tortured and abused, usually without any clothes on. And most of them are drawn with penises. Weren't you a little ... creeped out?

Of course! It's definitely disturbing stuff. These scenes are definitely graphic and weird, but -- at least in his mind -- he was the savior to these children. He was trying to protect them from evil forces. Who knows what it was in his background that caused him to want to be that -- it's all speculation.

Sacred Heart: Explosion (part one of the diptychDo you think he was insane?

I think maybe "eccentric" is a better word. I doubt he ever molested children or anything like that; it's entirely possible that he used this as an obsessive outlet to control those impulses. But was he insane? On the continuum of insanity, he was probably skewed toward one end of the scale.

Darger always seems to be pitting his spiritual side against his dark, "glandular" side. Is there something universal in this?

Well, I think there's something redeeming to what he did, or I wouldn't have decided to write a piece about it. It definitely has social value. And the intention of the artist is something that's always up for debate. But when I first saw his work, I was completely blown away.

Sacred Heart: Explosion (part two of the diptych)

Why did you pick this particular painting?

This is rather a unique painting for Darger; it has a certain amount of formalism to it that the others don’t.

And what attracted me to it is the abstraction -- the others are more narrative and straightforward. This one abstracts his ideas, and encompasses what he’s trying to do with his whole work.

If I were going to write a book on Darger I’d use this painting as the cover.

In your earlier piece on James Hampton, you took some compositional cues from the artist's own techniques. Did you do this with Darger, too?

Yes, to a certain extent; there's a huge amount of detail, obsessive detail, applied to every note in this piece, and I felt like I was channeling Darger's process in that way.

Darger also copied pop images into his paintings -- things like Coppertone ads.

Sure; Darger traced in images, so I traced a hymn into Sacred Heart: Explosion in the same way he traced a heart from some medical text. And the formal aspect of the piece I wrote mimics the formal aspect of the painting. My piece is in two parts, like the painting; the hymn that's presented in the first half is exploded in the second half.

Other serious composers -- people like Wolfgang Rihm and Terry Riley -- have also been building on the work of outsider artists. Do you see a trend?

I don't know -- but it's interesting, the connection that musicians feel for outsider art.

Henry Darger Why is that?

With most outsider artists, there's a certain amount of purity to what they did. Since outsider artists aren't trying to make any sort of commentary, their work functions more as a blank canvas for musicians. And then, writing a piece of orchestral music is an extremely obsessive process -- there's a connection with the kind of focus and dedication you see in Darger's works.

There's also the fascination with visionaries; in a lot of cultures, people thought the insane had a direct pipeline to God.

Sure -- there’s certainly a long tradition of outsider artists who incorporate religious iconography into their work, and in fact that’s one of the requirements for artists for me, that I’m working on; they have to be American-born, they have to be outsider or visionary artists, and they have to have incorporated Christian iconography into their work. Speaking in tongues, particularly intense religious devotion, is not that far off from what these artists have done. They've just done it in a more unique and special way. For me, music is the closest thing I've come to in terms of spirituality. It comes back to the idea of artistic purity. I think all these concepts are linked to one another.

So, do you see yourself as a sort of interlocutor between people like Darger and the rest of us?

I suppose. I’m definitely trying to spread the gospel of these guys – they deserve to be much better known than they are. These pieces are not tongue-in-cheek in any way; they’re done with the utmost respect for these artists. They're meant to be an homage to what they've accomplished. It’s a beautiful thing to me.

Would you ever do a piece based on the work of an outsider musician? Someone like Moondog, say, or … Tiny Tim?

The distance that I have, as a musician, to the visual artist is why it works; for musical outsider artists, it’s almost too close. So I don’t think I would, no. Translating these visual images into the language of music is the process that makes this work.

You still have one more part of the trilogy to write; how’s it coming?

The current timeline is for 2010 -- hopefully. It’ll be nice when it’s done.

The New Face of Afrobeat

By Stephen Brookes

The Washington Post, September 23, 2007

It's a gritty afternoon in a gritty parking lot in a gritty South Baltimore neighborhood, and the crowd is starting to fade. For the past five hours at this human rights rally, poets and rappers have been taking the stage to one-up one another's outrage, and now even the most anguished cries -- "the beast of the United States is eating wherever it wants!" -- are met with little more than polite nods. The sky's getting dark, the slogans are getting tired, and you can see people thinking that the struggle for justice should maybe just take the night off.

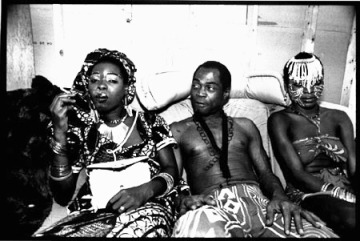

Fela Anikulapo Kuti, originator of Afrobeat

But then a new band takes the stage -- and suddenly a driving pulse erupts, powerful and irresistible. It's unlike anything else at the rally that day. This is no clumsy rapping or earnest revolutionary poetry -- this music has the drive of 1970s funk, the subtle rhythms of Yoruba tribal music, the fire of Ghanaian highlife. And when the five-piece horn section kicks in, driving the energy higher, everybody -- everybody -- starts dancing.

"We're here tonight to see people get active!" shouts the band's leader, pumping a fist in the air. "Otherwise, it's all over!"

The music is Afrobeat -- a fiery brand of political dance music pioneered in the 1970s by the Nigerian activist Fela Kuti -- and the group is Chopteeth, a 14-piece big band that's part of an Afrobeat revival across the United States. Thirty years ago, Afrobeat was the most important new music in Africa, fusing James Brown-style funk, African rhythms and urgent messages of political confrontation. But it never became an international phenomenon like reggae, and nearly vanished a decade ago when Kuti died.

Over the past few years, though, this profoundly African music has found a new home -- in America.

"There's a surge of interest now in Fela's music," says guitarist Michael Shereikis, 38, who leads the D.C.-based Chopteeth. "Virtually every song he wrote is a protest song, and they have a lot of resonance today. We do one song of his called 'Alagbon Close,' which is about torture in prisons -- a very timely thing to be singing about."

But building on Kuti's legacy is no easy task. A larger-than-life figure who famously married 27 women and battled a succession of military governments, Kuti was a maverick whose music was inseparable from his political life. Born in 1938 to a middle-class Nigerian family, he'd started as a fairly average, mainstream bandleader in Lagos in the 1960s. But after meeting the Black Panthers during a 1969 trip to Los Angeles, he quickly became radicalized -- and set out to change history.

Returning to Nigeria, Kuti reinvented himself. He adopted the name Anikulapo ("he who carries death in his pouch"), set up a radical commune called the Kalakuta Republic and began taking on Nigeria's military rulers with a new style of music he called Afrobeat. It was ferocious, satirical music, combining raw lyrics with a big horn section and lots of percussion. Kuti would spin songs out for half an hour or more, drawing people in with the seductive rhythms -- before delivering a sharp, devastating attack on the government.

Afrobeat made him famous, but it also set off riots and brought vicious retribution. Kuti suffered -- his commune was burned, his mother was thrown from a window, and he was arrested repeatedly on what most agreed were trumped-up charges. When he died in 1997, after years of harassment, more than a million people turned out in the streets to mourn him. And the music, tied so closely to the man, seemed to die with him.

An ocean away in Brooklyn, meanwhile, a young musician named Martin Perna was wondering why no one was picking up the torch. "It was tricky in the beginning to find anybody who even knew what this music was," says Perna, who went on to form the 12-member Afrobeat band Antibalas in 1998. "But Afrobeat was a way for me to merge my political convictions with my convictions as a musician. It's inherently a music of resistance and a music of struggle, and if you're going to reach people with any sort of message, you've got to put it to a beat."

Shereikis (l) and Mwalagho of ChopteethAntibalas (Spanish for "bulletproof") quickly won converts -- the band now puts on more than 100 shows a year in the United States, Canada, Europe and even Africa, and is widely considered the best Afrobeat band in the world.

Dozens more bands have been formed across the United States, raising the level of playing (many are conservatory-trained), writing new music and developing the style in surprising, inventive ways.

For Shereikis, the path to Afrobeat was a surprise even to himself. A self-taught guitarist, he'd been exposed to African music as a Peace Corps volunteer in the Central African Republic in the early 1990s. But he was working on a PhD in cultural anthropology from Tulane -- and contemplating a career in academia -- when bassist Robert Fox approached him in 2004 and suggested they start an Afrobeat band.

"I thought he was insane," says Shereikis. (In fact, the band takes its name from a Kuti song meaning "crazy person.") "But my one stipulation was that we mix it up with rumba, highlife, jazz and other kinds of music. We play a lot of Fela's music, but we're going in a new direction."

As the band has grown to include members such as Kenyan singer Anna Mwalagho, the superb trumpeter Justine Miller and reedman Mark Gilbert (who's played with everybody from the Temptations to Root Boy Slim), the influences have expanded even further. The band's first CD -- planned for release by the end of the year -- will be "a strange new crop of songs," says Shereikis.

Reinventing Afrobeat may be the key to its survival, its proponents say. The music is unlikely ever to enter the mainstream -- "there's too much stuff in Afrobeat for the market to dumb down," says Perna -- but if it's going to take root in American soil, it needs to adapt. The new players are hardly African firebrands. They tend to be American, white and mostly suburban. The music even seems to be turning into new, hybridized genre -- call it American Afrobeat -- with an agenda of its own.

"Most of the groups doing Afrobeat are either multicultural or predominantly white," says Perna, whose own background is Latino.

"How they address the privileges they enjoy -- male privilege, class privilege, skin color privileges -- will give American Afrobeat its depth; looking within themselves, rather than just pointing. Anybody can point a finger at George Bush, or the Iraq war, or police brutality, and write a song about it," he says. "But the real depth comes from examining these other systems of privilege. And we try to do that in our music."

And as far as Shereikis is concerned, the Afrobeat revival makes perfect sense -- even if it is happening in America.

"There's a lot of anger and frustration in the United States right now. So we try to think big, to address the macro political issues," he says. "The groove is important -- it's what keeps people feeling good and dancing. But the point of setting that stage is to get your message across."

From the Levine, Unpolished Gems

By Stephen Brookes

The Washington Post September 22, 2007

Of the many great accomplishments of the 20th century -- penicillin, jazz, on-time pizza delivery -- the wealth of new music for wind quintet must surely rank close to the top. There's not much of interest from earlier centuries; Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms and the other gods pretty much ignored the genre. But as the Levine Woodwind Quintet demonstrated at the Mansion at Strathmore on Thursday night, there's a rich repertoire from the last century to be mined -- with a number of strikingly beautiful gems.

The pensive Sir MalcolmTake, for instance, the two works that opened the program: Vincent Persichetti's 1951 "Pastoral" and Irving Fine's "Partita," a set of free variations from 1949. There's no harsh, midcentury thorniness here; these -- like the rest of the works that were on the program -- are melodic, light-filled pieces that delight in the flavorful sonorities of the woodwinds. There was, as you'd expect, some inward-looking pensiveness in Malcolm Arnold's "Divertimento" (for flute, oboe and clarinet), and Shostakovich brought his trademark irony to his two "Preludes" (for flute, bassoon and clarinet). But the overall tone of the evening was best evoked by Darius Milhaud's "La Cheminee du Roi Rene": lighthearted, highly sophisticated and immensely pleased with itself.

While it was a fascinating program, though, the execution fell a bit short. The lightness and quick wit of this music demands a deft touch and razor-sharp precision, which wasn't always in evidence. And despite some fine individual performances, the Levine players didn't have their ensemble playing fully under control, and many of the pieces felt under-rehearsed and lacking in confidence -- a performance more dutiful than exuberant.

The National Philharmonic at Strathmore: Blocks Unbusted

By Stephen Brookes

The Washington Post • September 18, 2007

Saturday night's concert by the National Philharmonic was billed as a "Symphonic Blockbuster," but a good crowd turned up at the Music Center at Strathmore anyway, hoping for the best. To little avail, alas. The program -- titled "National Voices" -- was one of those unimaginative, play-it-safe affairs, with not one, not two, but three sagging old warhorses trotted out.

Sandy CameronFirst up was Sibelius's "Finlandia" from 1900, painted in broad strokes by conductor Piotr Gajewski with much heroic crashing, little subtlety and a pale sort of grandeur. Smetana's much-loved "The Moldau" got a similar treatment.

Then there was Aaron Copland's "A Lincoln Portrait" from 1942. It's a war-effort piece in which a speaker reads excerpts from Lincoln while the orchestra plays Copland's soaring Americana. Montgomery County Executive Isiah Leggett brought a low-key approach to the speaker's role, and the most interesting aspect was the irony of Lincoln's words: "Fellow citizens, we cannot escape history. We of this Congress and this administration will be remembered in spite of ourselves."

Maybe it's just that "nationalist music" has become an outdated idea; the most exciting music these days is written by composers (Tan Dun, for instance) who leap among musical cultures with imagination, wit and cheerful disregard for national borders. At any rate, it was the only non-nationalistic piece on the program, Sibelius's Violin Concerto, that saved the show. And much of the credit goes to the brilliant 22-year-old violinist Sandy Cameron, who played this rhapsodic work with passion and engaging, thoughtful intelligence.

The Puppini Sisters: Glamour at the Birchmere

By Stephen Brookes

The Washington Post • August 30, 2007

Strange and beautiful things happen when you stumble into a time warp. Take Tuesday night at the Birchmere, for example, where the Puppini Sisters -- a new glam-girl trio from Britain -- channeled the 1940s stylings of the Andrews Sisters and mixed it up with late-20th-century pop. Bizarre? Sure. But until you've heard Blondie's "Heart of Glass" or the Bangles' "Walk Like an Egyptian" sung in swing-era harmony -- complete with synchronized hip-rocking -- you don't know what you're missing. Formed just a few years ago, the Puppinis (not actual sisters, but they sing like it) owe an obvious debt to the Andrews Sisters -- they even opened the set with "Bei Mir Bist Du Schon," the Andrewses' first hit. But this is no mere homage band, unless it's homage to glamour in general. Strutting around the stage in silky 1940s gowns, the Puppinis sang blazing, tightly knit three-part harmony with absolute nonchalance, shifting effortlessly from standards like "Mr. Sandman" to the mambo-flavored "Sway" to a sexy, sultry "Java Jive."

Formed just a few years ago, the Puppinis (not actual sisters, but they sing like it) owe an obvious debt to the Andrews Sisters -- they even opened the set with "Bei Mir Bist Du Schon," the Andrewses' first hit. But this is no mere homage band, unless it's homage to glamour in general. Strutting around the stage in silky 1940s gowns, the Puppinis sang blazing, tightly knit three-part harmony with absolute nonchalance, shifting effortlessly from standards like "Mr. Sandman" to the mambo-flavored "Sway" to a sexy, sultry "Java Jive."

While their takes on the standards were stylish and imaginative -- they even made "Jeepers Creepers" sound good -- it was their reworking of newer material that lifted the Puppinis into a realm of their own. Not everything glittered (the old Classics IV tune "Spooky" could have been left on the ash heap of history), but Kate Bush's "Wuthering Heights" got a much-needed revival, and an upbeat version of Gloria Gaynor's "I Will Survive" brought down the house. The best songs of the night, though, were the Puppini originals -- a hilarious, mock-bluesy lament called "I Can't Believe I'm Not a Millionaire" and the rueful "Jilted Again."

The Sisters -- Marcella Puppini, Stephanie O'Brien and Kate Mullins -- sang flawlessly all night. And, while they accompanied themselves on (respectively) accordion, violin and melodica, the band's superb rhythm section (Martin Kolarides on guitar, Henry Tyler on drums and Nick Pini on bass) kept things moving with subtle, understated power and precision.

From Sierra Leone, Songs of Survival

By Stephen Brookes

The Washington Post • August 21, 2007

Does any band have a more gut-wrenching back story than Sierra Leone's Refugee All Stars? Forced to flee the country's nightmarish civil war in the late 1990s -- when rebels routinely chopped off civilians' limbs -- group members met in a refugee camp across the border in Guinea. Pushed from camp to camp, coping with disease, poverty and the slow erosion of hope, they formed a band and began performing -- and suddenly shot to fame after being discovered by a team of documentary filmmakers. "This is the soundtrack for the life we've been living," the group's leader, Reuben Koroma, told the crowd Sunday night at the State Theatre in Falls Church. The band has become the voice of displaced people everywhere, and their songs take on everything from the horrors of war to the dull grind of refugee life. But it's not a catalogue of complaints -- the All Stars' music is relentlessly upbeat and even joyful, full of lilting Caribbean rhythms and African folk influences. "We're living!" shouted Koroma triumphantly at one point. "We survived!"

"This is the soundtrack for the life we've been living," the group's leader, Reuben Koroma, told the crowd Sunday night at the State Theatre in Falls Church. The band has become the voice of displaced people everywhere, and their songs take on everything from the horrors of war to the dull grind of refugee life. But it's not a catalogue of complaints -- the All Stars' music is relentlessly upbeat and even joyful, full of lilting Caribbean rhythms and African folk influences. "We're living!" shouted Koroma triumphantly at one point. "We survived!"

But as the band worked through the songs from its CD "Living Like a Refugee," it slowly became clear that, for all their amazing resilience, the All Stars are a fairly average band -- lively and fun, but a lot like something that you'd hear at a jump-up on a Caribbean beach. Guitarist Ashade Pearce got in a few nice licks, and the young singer Alhaji Jeffrey "Black Nature" Kamara had an amazing growling, fast-paced delivery, but the rest of the nine-piece band just cranked out the rhythm, and the songs all blended into each other in a feel-good blur.

Far more impressive was the opening act, D.C.-based Afrobeat band Chopteeth. Fronted by guitarist and singer Michael Shereikis, the 13-piece group is a storming powerhouse of big-band African funk rooted in the music of the Nigerian bandleader Fela Kuti. Playing a mix of music by Kuti as well as originals, Chopteeth was smart, tight and relentlessly driving -- and with a horn section led by the searing-hot trumpeter Justine Miller, a definite don't-miss.