The Murder of Rio's Street Kids

By Stephen Brookes

In Rio de Janeiro for Insight Magazine

On a warm, humid morning in December, children playing in a waste dump near Rio de Janeiro stumbled onto two battered and abandoned bodies. Both were girls; one had been raped and mutilated before being shot in the head; the other had been beaten and then shot repeatedly. And the girls were still children -- kids who lived on Rio's tough and dangerous streets.

Photos by Brig CabeThere are, according to UNICEF, around 12 million children living by their wits on the streets of Brazil. Some have families they see from time to time, but a huge number are simply abandoned. Sleeping in doorways or on beaches at night, they swarm over the big cities in packs -- there are tens of thousands of them in Rio de Janeiro alone, and Sao Paulo and Recife have thousands more.

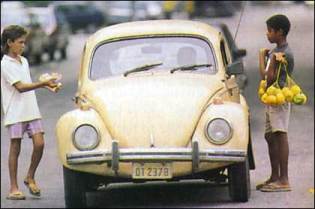

They seem to be everywhere: begging in front of restaurants, peddling cigarettes in sidewalk cafes, shining shoes outside the train station, washing clothes in public fountains. Take a morning stroll on the elegant, black-and-white mosaic sidewalk that curves along Rio's Copacabana Beach and you'll see dozens of them, sleeping under the palms. And as the country plummets ever more deeply into economic chaos, there are more kids on the street every day.

As their ranks have multiplied, so has petty crime, both in the cities and the sprawling shantytowns known as favelas that surround them. Much of the blame, ironically, can be put squarely on Brazil's juvenile justice code, which makes it next to impossible to lock up anyone under the age of 17. If a kid is arrested, whether for the first or the 40th time, he's usually back on the street in 48 hours or less with a slap on the wrist.

Armed with that virtual guarantee of impunity, kids as young as 5 and 6 years old have taken to crime in droves. Some work for drug dealers, some become prostitutes, some pick pockets and snatch purses, some form gangs and rob pedestrians with knives and broken bottles. As neighborhoods have become more dangerous, small groups of vigilantes or death squads, as they're known have implemented their own, bloody system of justice.

Last year, according to government statistics, 492 street kids were murdered in Brazil, many of them gruesomely mutilated. Other groups, like Rio's National Movement for Street Children, say the figures are even higher. "From January 1988 to December 1990, 4,611 kids were assassinated," says Volmer do Nascimento, the group's director (and a former math teacher with a penchant for quoting statistics from memory). "That's 4.2 kids a day," he adds. "Every day. And it's getting worse."

The kids get killed for almost any reason. Some are thieves who prey on shopkeepers; the shopkeepers, unable to get them jailed, hire gunmen to solve the problem. Others work for drug gangs or crooked cops and get in over their heads. Some are witnesses to other crimes and have to be eliminated, a practice known as "burning the files."

Some, according to social workers, are simply killed for being street kids. When the body of 9-year-old Patricio Hilario da Silva was found on a main street in Ipanema in 1989, there was a handwritten note tied around his neck. "I killed you because you didn't study and had no future," the note read. "The government must not allow the streets of the city to be invaded by kids."

The death squads, which often include ex- or off-duty cops, have proliferated through the favelas -- one study found 15 groups in the Baixada slum alone -- as de facto police. They are generally supported by the people there, who get little or no protection from official police.

Judge Darlan: Death squads target "anybody""The death squads don't just kill children," says Judge Siro Darlan of the juvenile courts. "They go after criminals, homosexuals, old people, anybody. They exist because the government can't guarantee security to the people. So it's a threatened population that takes things into its own hands."

"We're living in a society of generalized violence;' agrees Roberto dos Santos, a Rio social worker. "The public doesn't believe in justice, or in the leadership. So there's a widespread feeling that violence is a cure for the problems."

Three of every four homicides in Rio go unsolved, according to one of the city's public prosecutors. "The police are almost completely ineffective," says social worker Nascimento. "In Duque de Caxias [a Rio favela], 919 people were killed in 1989, according to official statistics. In 281 of those cases, the police could identify the killers. But only 25 of those have been brought before a judge, and only eight were convicted."

A low conviction rate is not, of course, directly the fault of the police. In the lawless favelas, witnesses are often understandably afraid to come forward to testify; in Rio alone, at least 13 prosecution witnesses to death squad killings have been murdered since 1983. And juries are often unwilling to convict, partly because of the danger of reprisals, but also because a large part of the population condones vigilantism. In Sao Paulo, the gangs are called justiceiros -- "justice bringers."

Disdain for the police has become so pervasive, in fact, that even spontaneous mob lynchings are becoming common. When three men tried earlier this year to steal a van in Rio's middle-class neighborhood of Jacarepagua, the van's driver smashed it into a tree and fled, screaming for help. A crowd started chasing the thieves, caught one of them, then tied him to a tree. As the crowd swelled to more than 50 people, someone doused him with gasoline and set him on fire. He burned to death.

Police say the death squads earn $40 to $50 for killing a street kid and as much as $500 for an adult. In January, Health Minister Alceni Guerra said the government had evidence that "businessmen are financing and even directing the killing of street children." The military police confirm this. "There are groups that are paid by businessmen to protect their shops," says Maj. Altanir Freitas. "But since the community protects these groups, it's hard to find out who they are."

Some of the death squads are hired by drug dealers. According to Freitas, the drug gangs extend a great deal of social control over the favelas. They'll give the kids food and protection in exchange for working for them, and for not causing trouble for their customers. "Dealers try to give the impression they're acting on behalf of the community," he says. "If a kid starts making trouble, committing crimes, they might kill him."

Or if he just knows too much. "The kids are used as avions -- runners for the dealers," says Judge Darlan. "They take the drugs from dealer to seller, and eventually they get to know who the dealers are, where the drugs are hidden, where the group's headquarters are. That's why they become dangerous and get killed."

The death squads have a pedigree, of sorts. They've been around since the 1950s, when the military regime allowed them to freely wipe out criminals and political opponents. They've been outlawed since the mid-1980s, but police involvement is said to be so strong in some areas that entire police forces have been disbanded. With salaries abysmally low -- a starting cop earns about $100 a month -- it's not surprising that they look for outside work. A report last year from the Rio police said that fully half of the members of the city's death squads are off-duty or ex-cops.

For Rio's street kids, life is nasty, brutish and usually short. Few bother to bathe, and most own only the clothes on their backs and the money they can hide in their sneakers. Parasites and lung infections are common. They spend the day hanging out at the beach or in the parks, begging, sniffing glue or stealing. Some "guard" parked cars for a few cruzados or make money delivering messages. They're often beaten by the police or older kids, and every day at least one turns up dead.

Many are thieves, but there are other ways to get by. Prostitution is common among the kids. "There are 12-year-old boys who have wives," says Darlan. "We've seen girls as young as 9 years old prostituting themselves for a few dollars, both to other kids and to adults." Some are controlled by pimps, who fix them up with foreign tourists. As a result, says a former child prostitute who now counsels kids, AIDS has become rampant.

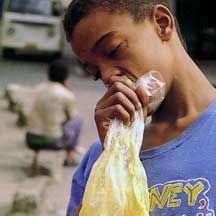

Drug use is rampant among the street kidsDrug abuse is almost universal -- especially glue, which is cheap and widely available. They put a little into a plastic bag, stick their faces in and breathe the fumes for the hallucinogenic effects. Most kids, says social worker dos Santos, go to sleep drugged. He says that glue sniffing is common among the youngest kids, but that they move on to marijuana and cocaine as teenagers. Even heroin, once rare, is more widely available.

"Ninety percent of the kids who come through here are addicted to marijuana, cocaine or glue, because they get involved with the drug gangs," says Darlan. "It's how they get paid by the dealers. They try to get them hooked."

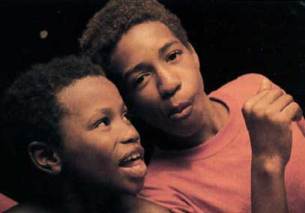

At night, life gets more dangerous; most kids band together for protection against other gangs, and against the police. They sleep in doorways, in huddles around the train station, in the parks along Guanabara Bay on the city's eastern edge.

There's a real threat from the cops. "I got arrested once -- they didn't tell me for what," says Paolo Costa, a street thief. "Two cops beat me up, then took me to the police station. Then they let me go." Other kids have told social workers that the police make them eat cockroaches and excrement, and burn them with cigarettes. To protect themselves, older kids will sometimes press-gang younger ones into standing watch through the night, and some of them have learned tricks to keep the police away. "They carry razors," says one social worker. "If a cop hassles them, they threaten to slice their own faces up and blame the police."

The military police headquarters is a sullen, prison-like compound that dominates the block of Evaristo da Veiga Street, a few steps from the Cinelandia district in downtown Rio. At the arched entry, guards in blue uniforms and submachine guns lounge watchfully. Upstairs, in a huge chamber dominated by portraits of former police chiefs dating back to the late 1800s, Col. Carlos Cerqueira denies that he runs what many critics call a profoundly corrupt and inefficient operation.

"They call themselves policemen and defenders of the community," he says of the off-duty cops arrested as members of death squads. "But of course they're not. They're criminals."

Police Chief Cerqueira: a tough jobCerqueira has a tough job. While considered personally honest, he presides over a poorly paid force with a tradition of taking the law into its own hands. Many members still act, as an Amnesty International report accused last year, "as if they are beyond the law, torturing with impunity and increasingly resorting to extrajudicial measures."

Examples are plentiful. Last March, for in stance, a young woman named Adriana Ceres Buenos was killed by a police officer while riding as a passenger on a motorcycle through downtown Rio. The officer signaled the driver to stop for an inspection; when he didn't, the cop pulled out a pistol and fired, hitting Buenos in the back. She was 17.

Corruption, too, is endemic. "When the cops catch kids committing crimes, they split up the kids' money," says Fabio, a 13-year-old shoeshine boy who has worked Copacabana's restaurants for five years. "Only the military police are corrupt the civil police are honest. But the military police threaten us. They ask us to steal for them. Sometimes they ask us to sell drugs to tourists."

Why? "Kids will go up to tourists and ask them if they want to rent an apartment or a cheap hotel room. Then they offer to sell them drugs -- marijuana, cocaine, you know. They take the tourists down to the beach and give them the drugs, but the police are watching. And they come down and arrest the tourist, and ask them for a bribe. They ask for $3,000. But they take what they can get."

Police also apparently still torture suspects to get evidence or information. While torture was strictly outlawed in the country's 1988 constitution, prisoners regularly charge that they have been beaten, given electric shocks, had their heads held underwater and been tied upside down hanging from an iron bar -- a position known as "the parrot's perch."

Take the case of 14-year-old Marcelo Moreira Pacheco. While playing with a friend, 13-year-old Andre Leota, one summer afternoon, they were assaulted by three men. Marcelo got away, but Andre vanished. When Marcelo went to his friend's house the next day, five military police arrived and took him to a hut in the favela, where they tortured him with electric shocks to his fingers, anus and other parts of his body. After a few hours, he was handcuffed, driven to a new location and tortured some more, this time joined by more military police. Altogether, Marcelo was tortured and detained for 12 hours before the police released him, he said in his official complaint. But he was lucky. Shortly after Marcelo was released, his friend Andre was found on a waste dump. He was dead.

As the dull roar of evening rush-hour traffic filters up from the street and through the thin curtains in his office, Police Chief Cerqueira nods his head slowly when asked about such reports and says they've been exaggerated. But he admits that he's been coming under growing popular pressure to solve, through whatever means necessary, a problem that is beyond his control. "The public isn't happy. They want us to be tougher with homeless kids and get them off the streets." He pauses, frowning. "In the developed world, people don't question whether a kid has the right to live if he's broken the law. In Brazil, we're still discussing it."

It's a hot June afternoon in Fatima, a beat-up Rio neighborhood of squat, drab buildings and crowded streets that reverberate with the blare of radios and car horns. Just overhead, along the lush green spine of hills that wind through the city, floats the upper-class neighborhood of Santa Teresa, an oasis of turreted houses and well-tended gardens. Fatima, down below, is gritty, rough, raucous. Paolo, a wiry kid with an aggressive swagger and a raw, phlegmy voice, is hanging out with friends near a bar in Riachuelo Street. He hasn't seen his family in five years, he says. He survives by attacking people and robbing them. He's 14.

"We make 15,000 cruzados [about $50] a day ripping people off," he brags, scratching a rash down the side of his neck. Like most kids who sleep on the streets, he has skin infections and bronchitis. His eyes dart around alertly as he talks, taking in everything and everybody that goes by, like a predatory animal. "Three or four of us will go out and get around some guy. Women are best, they get scared real fast. We stick a broken bottle in their face, and they start to fart." His friends crack up at this. "They're shakin' and sweatin', and we just take their money. Yeah. It's easy."

Paolo's turf stretches across the heart of downtown Rio, from the trendy restaurants and theaters of the Cinelandia district up to the train station, where he sleeps most nights with his girlfriend and his gang. He can usually eat for free at one of the church-run shelters scattered around the city, but after they close in the late afternoon he gets his gang together for the evening's hunt. When night comes, they'll need money -- for glue to sniff, for cigarettes, for the samba dance halls.

Solitary kids will snatch purses, but the smart ones form gangs, which also gives them protection from other, bigger street kids. There's a standard repertoire of techniques they use: Some will stretch out along a block, even a crowded one in the middle of the day, pick a target and close in on him slowly from different directions. Or they'll dart out together from a doorway or alley, surround the victim and go through his pockets, then take off in different directions. In the tourist areas, one member will approach a prospective victim and ask for the time; answering in English marks you as a target, since foreigners usually have money, rarely go to the police and are often getting ready to leave the country. Some of the kids rob people while pretending to sell them cigarettes or gum. And prostitutes who in Rio are often transvestites walk up to men on the street and stroke them, while an accomplice comes up from behind.

Solitary kids will snatch purses, but the smart ones form gangs, which also gives them protection from other, bigger street kids. There's a standard repertoire of techniques they use: Some will stretch out along a block, even a crowded one in the middle of the day, pick a target and close in on him slowly from different directions. Or they'll dart out together from a doorway or alley, surround the victim and go through his pockets, then take off in different directions. In the tourist areas, one member will approach a prospective victim and ask for the time; answering in English marks you as a target, since foreigners usually have money, rarely go to the police and are often getting ready to leave the country. Some of the kids rob people while pretending to sell them cigarettes or gum. And prostitutes who in Rio are often transvestites walk up to men on the street and stroke them, while an accomplice comes up from behind.

With such thefts increasingly common, savvy Rio residents go around prepared. "You always carry something in your wallet, so they get something if they rob you," says Ricardo Silva, a teacher. "Otherwise they get mad and cut you."

At 9.30 on a clear Wednesday morning, the hard wooden benches that line the halls of the Juizado de Menores in Rio are already crowded with kids and their mothers waiting to be processed through the juvenile justice system's revolving door. Social workers with armfuls of manila files trudge back and forth, locating parents, making arrangements for kids to meet with counselors, setting court dates. It's clear from the looks of boredom and amusement on the faces of the kids that most have been here before and that they're not impressed. But on the faces of the mothers there's a different expression: pain, humiliation and fear.

Siro Darlan is the chief judge of the system. A direct, no-nonsense guy in his early 40s, he's partly judge, partly counselor and partly father to kids who have few adults they can trust. Darlan's task is to get kids out of street crime and into productive lives. But the laws are so watery that it's a largely impossible job.

Under the country's juvenile code, once a child is arrested he's quickly brought before a prosecutor, who tries to locate the parents and then makes a recommendation to the judge. For a first offense, a kid usually will get a stern talking-to and be set free. Repeat offenders will meet with social workers, who try to get them placed in simple jobs, as office messengers for instance, or send them to a job-training program run by a church or private relief agency. Only if a child is guilty of a serious crime -- armed robbery, say, or murder -- is he sent to a juvenile detention center, for a maximum stay of three years. But the centers aren't jails, and there's no real security. The kids sneak out at night quite regularly, says Darlan. And there are so few beds available that many kids are simply released.

That kind of impunity makes them valuable to adult criminals, many of whom are former street kids. "They use the kids as shields," says Darlan. "And the kids go along with it. The kids know they won't be punished, so sometimes they assume guilt for things they haven't done, to protect the adults. And all this gives them a feeling of power -- they feel like they can get away with murder."

About 2,000 kids a year are arrested, the majority -- about 80 percent -- for stealing. For most, it's not their first encounter with the courts. "This is the file of a 16-year-old girl who's now in one of the shelters," says Darlan, plunking down a stack of arrest reports that's at least 6 inches thick. "Theft, robbery, gang formation. Twenty two arrests." He stops, leafing through the buff-colored forms. "The first time, she was 6 years old.

"It's a tragedy, really," he continues grimly "By the time these kids get here, they're already very worldly. There's not a lot we can do to keep them from getting in trouble again."

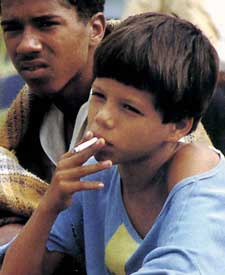

It's late on a weekday evening in Copacabana, the thin strip of glitzy hotels, expensive apartment buildings and hard-currency jewelry shops that stretches for miles along Rio's most famous beach. A tiny kid with the unlikely name of Anderson is wending his way through the tables at an outdoor cafe called Mab's, peddling cigarettes and gum to the customers. At this hour there aren't many, just a couple of prostitutes and some tourists. The breeze off the ocean has turned cold, but he's barefoot and doesn't have a shirt. "Dirty," he explains, with a shrug. Nine years old, he works from 4 p.m. to midnight and makes $3 to $6 a day. He buys Marlboros for 50 cents a pack downtown, then brings them to Mab's to sell for a dollar.

Anderson (l) sells cigarettes to surviveWith his 13-year-old brother Enrique, a shoeshine boy, he takes a bus to Copacabana every afternoon from the shantytown north of the city where he lives. The trip takes about an hour and a half, and they do it six times a week. Some of what they earn they give to their mother, who works as a maid. "We split the money half-and-half " says Enrique, a tall, likable kid who looks after his brother. "I always have a little saved."

Anderson and Enrique are typical of another breed of street kids, the ones who still live with their parents but have to help support their families. With the Brazilian economy in a shambles -- the gross national product has been growing at a sluggish 3 percent a year for the past decade, and the country is mired in a debt of $111 billion -- hundreds of thousands of people have been streaming from the country into the cities in search of jobs. But with housing in Rio at a premium, they settle in the sprawling shantytowns that spread up and down the steep hillsides of the city and into the northern suburbs.

With names like Cidade de Deus, Baixada Fluminense, Rocinha and Duque de Caxias, the favelas are warrens of narrow, unpaved alleys and sewers running between precarious shacks crammed up against each other. Most have electricity, but plumbing is primitive at best. Drug addiction, alcoholism, prostitution and child abuse are rampant, health care is nonexistent, and almost one in three kids is born to an unwed mother.

No one knows just how many people live in favelas, but it's in the millions. Rocinha alone is thought to have nearly 150,000 inhabitants. "These are people on the edge of society," says Marcos Maranhao, head of the mayor's office on street children. "The kids don't get affection, food, any kind of social structure. They don't even have basic sanitation -- though of course most have television!"

Marcia Bandeira de Mello Leite, a sociologist at the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, says more than half of Brazil's children between the ages of 10 and 17 live in families earning less than $30 a month per person. School conditions are atrocious, she says, and it's common for kids to drop out and go to work; in some parts of the country, only one child in 10 makes it to the eighth grade. "More than half the kids between the ages of 15 and 17 are working," she says, "and about 18 percent of kids aged 10 to 14. Kids under 14 aren't allowed to work, but employers turn a blind eye. They can get the kids cheaply."

Some kids have no choice: They've been abandoned and have to work if they want to eat. But even children with families figure out that they can often improve their condition by moving out. "A lot of these kids live in families where the mother is a prostitute or the father is an alcoholic, they get beaten regularly, and they don't get enough to eat," says dos Santos. "Then they find out that if they live in the street and start committing crimes, they can eat, they can buy clothes, they can even save money. So they leave."

For most of Rio's street kids in the struggle for survival, the street eventually wins. But a few manage to escape, with the help of a loose network of churches, juvenile shelters, street educators and private aid groups that try to turn their lives around. There are an astounding number of groups that claim to help street children -- 522 of them, according to the mayor's office -- but only a handful that make much of an impact. The two government-run institutions, the State Foundation for Minors and the National Foundation for the Welfare of Minors, house kids convicted of serious crimes, and both, according to Amnesty International, have reputations for mistreating them.

Social worker Nascimento brings help to the streetsSmaller, private centers, often funded by churches and staffed by volunteers, provide counseling, walk-in medical care and food. The Children's Crusade runs a half dozen centers where kids can learn trades -- pig breeding, for example -- and find relief from the streets. They send "educators" out at night to give the kids sandwiches and juice, clothes and medical help.

The most high-profile group is the National Movement for Street Children, which was started in 1985 by Nascimento. A small, very intense man with a rapid-fire way of talking, Nascimento has been skillfully using the national and international media to pressure the government to develop a national policy on street kids.

But national policy is of no interest to 10-year-old Jackson. He has been on the streets "for a long time" -- he can't remember when he got there, or much about the town he grew up in, or even his family. He sneaked onto the back of a truck headed for Rio because he "wanted to see the city." It's hard to understand a lot of what he says: At least six of his front teeth are gone, knocked out in fights. The left side of his face is smeared with a noxious-looking pink cream that a social worker gave him for an infection, and it gives him a diseased, slightly demented look. But Jackson doesn’t seem too concerned about his looks – he’s got bigger things to worry about. Like surviving another night on Rio’s mean streets.

(Insight Magazine, August 5, 1991)

References (27)

-

Response: ToxBox BlogRoger worked away at his books and at his theory, which he eventually had published in the SIAM Journal by the simple expedient of adding a Ph. D. to his name. He was found out, but he didn't care. Roger had applied for OCS at the age of twenty and had ...

Response: ToxBox BlogRoger worked away at his books and at his theory, which he eventually had published in the SIAM Journal by the simple expedient of adding a Ph. D. to his name. He was found out, but he didn't care. Roger had applied for OCS at the age of twenty and had ... -

Response: diwali

Response: diwali -

Response: Rehab Near Wyoming CitiesCedar Mountain Center 707 Sheridan Avenue Cody, Wyoming 82414 (307) 578-2421 Dewey Skansberg and Associates 3211 Energy Ln # 103 Casper, Wyoming 82604 (307) 265-2238 Alcoholics Anonymous PO Box 2266 Casper, Wyoming 82602 (307) 266-9578

Response: Rehab Near Wyoming CitiesCedar Mountain Center 707 Sheridan Avenue Cody, Wyoming 82414 (307) 578-2421 Dewey Skansberg and Associates 3211 Energy Ln # 103 Casper, Wyoming 82604 (307) 265-2238 Alcoholics Anonymous PO Box 2266 Casper, Wyoming 82602 (307) 266-9578 -

Response: Diwali Images 2016

Response: Diwali Images 2016 -

Response: Christmas

Response: Christmas -

Response: Thanksgiving Day Pictures

Response: Thanksgiving Day Pictures -

Response: veterans day images

Response: veterans day images -

Response: Sari

Response: Sari -

Response: eid mubarak images

Response: eid mubarak images -

Response: blades paintings knife

Response: blades paintings knife -

Response: https://www.dailysmscollection.com/

Response: https://www.dailysmscollection.com/ -

Response: happy Diwali Wishes 2017happy Diwali Wishes 2017

Response: happy Diwali Wishes 2017happy Diwali Wishes 2017 -

Response: Diwali Images

Response: Diwali Images -

Response: Happy New Year 2018 in Advance

Response: Happy New Year 2018 in Advance -

Response: Happy New Year Memes 2018

Response: Happy New Year Memes 2018 -

Response: Shooting Games

Response: Shooting Games -

Response: Killing Games

Response: Killing Games -

Response: Mother's Day wallapeper

Response: Mother's Day wallapeper -

Response: 4th of july 2018

Response: 4th of july 2018 -

Response: 4th of july in new york

Response: 4th of july in new york -

Response: merry christmas qoutes for cards

Response: merry christmas qoutes for cards -

Response: funny christmas meme

Response: funny christmas meme -

Response: Victoria Secret Bombshell bra Review

Response: Victoria Secret Bombshell bra Review -

Response: compostable nappies australia

Response: compostable nappies australia -

Response: Lifeguard certification

Response: Lifeguard certification -

Response: Best Lawyer Near MeBrown Stone Law

Response: Best Lawyer Near MeBrown Stone Law -

Response: LiveGuestPost.com

Response: LiveGuestPost.com

Reader Comments (9)

Excellent material.