Body Brokers: The Global Trade in Human Organs

By Stephen Brookes in New Delhi, Madras and Cairo

for Insight Magazine

Squatting in a dirt alley in the Indian slum of Villivakkam, the young man pulls up his shirt and runs his finger along the rough, 8-inch scar that erupts below his rib cage and runs down his abdomen into the folds of his skirt-like longyi.

In India, the kidney business is thriving"This is where they cut me open to get the kidney out," he murmurs, describing the operation he underwent in a Madras hospital three years ago. "They paid me 20,000 rupees (about $800) for it, half before and half after. It's all gone now," he says, laughing self-consciously. "I had a lot of debts, and I drank the rest. I was stupid, and now I'm sick. I can't even work anymore. I'm 27 years old, and if I carry a bucket of water down the street I have to sit down and rest."

It's a story that's becoming increasingly familiar across India, Latin America and other parts of the developing world: poor people recruited from slums and shantytowns to sell parts of their bodies for quick cash. The buyers: wealthy Japanese, Middle Easterners and Europeans who, frustrated with laws against buying organs in their home countries, go abroad to countries where they can check into a hospital, find a middleman to procure a donor, pay for the transplant and return home -- all in a matter of weeks.

"The practice is apparently widespread, from what we've been hearing," says an official with the World Health Organization in Geneva. "And we're very concerned."

The concern is warranted. With kidneys selling for anywhere from a few hundred to tens of thousands of dollars, the trade has become so lucrative that there have been reports -- some substantiated, some questionable -- of children in Argentina being stolen and killed for their organs, of Chinese prisoners executed and their kidneys sold, of prisoners in the Philippines being released after donating a kidney, of bodies washing up on Brazilian beaches with their organs surgically removed.

At one psychiatric clinic outside of Buenos Aires, Argentina, doctors have been accused of murdering lunatics for their body parts. Large, well-organized trafficking rings have even been uncovered: In December, Juan Andres Ramirez, Interior Minister of Uruguay, announced the arrest of 20 persons who were allegedly flying slum dwellers to other countries to "donate" their organs.

While some of the stories are patently untrue -- widespread reports in the early 1980s that Latin American children were being stolen and their organs sold to rich Westerners, for example, were later shown to be part of a bizarre Soviet disinformation campaign -- there are thriving, well-documented and quite legal markets in Bombay, Madras, Calcutta, Manila, Cairo and Hong Kong.

Many of the buyers are nationals, but much of the trade is fueled with oil money from outside. “Most or the buyers are coming from the Emirates, Qatar and Kuwait," says the World Health Organization official, describing the kidney business in Cairo and Bombay. "Apparently there's a big shortage of kidneys in the Gulf states right now."

The growth of this grisly trade has resulted from two related trends over the past two decades. On the one hand, medical and technological developments have raised the success rate of transplants and increased the demand for organs; but as demand has gone up, laws have been implemented in most of the world forbidding people to pay organ donors, thus cutting the potential supply. That imbalance has spawned a complex network of desperate buyers, shady middlemen, opportunistic doctors, and poor and uneducated donors.

While corneas, lungs and other organs can be transplanted from live donors, most of the trade is in kidneys, since a healthy, well-nourished donor can live reasonably well with only one. Since the first renal transplant was done in 1954 between twin brothers, the survival rate has gone up dramatically, thanks to advances in surgical techniques, the training of large numbers of transplant surgeons and the development of drugs such as cyclosporine that suppress immune system attacks on transplanted organs. For patients who suffer from chronic kidney failure, there is now greater hope that they can be released from the expensive, endless and intrusive mechanical process of dialysis (which cleanses impurities from the blood) and live a normal life with a transplant.

PHOTOS BY BRIG CABEBut finding a donor is not easy. Successful transplants rely on a good blood and tissue match between donor and recipient, and the best donors are often members of one's family But patients who lack a willing family member have only two choices: wait until a properly matched kidney from a cadaver becomes available, or go to one of the world's kidney marketplaces.

Until a few years ago it was possible in the United States and Europe to bring donors in from outside. As early as 1985, the World Medical Association noted that "in the recent past a trade of considerable financial gain has developed with live kidneys from underdeveloped countries for transplantation in Europe and the United States."

But as more and more such cases came to light, governments began to respond. Washington outlawed trade in body parts with the National Organ Transplant Act of 1984 -- sparked by the revelation that a doctor in Virginia had circulated brochures in the Caribbean, offering people a free two-week vacation in the United States if they agreed to leave a kidney behind when they went home.

Other Western governments soon followed suit. During the summer of 1988, Englishman Colin Benton died in a private hospital in London after a kidney transplant. The case attracted no attention until his widow revealed a few months later that her husband had paid about $3,000 for the kidney to a Turkish donor who had flown to Britain for the operation.

The case provoked an uproar, and the next year Parliament quickly passed the Human Organ Transplants Act of 1989, outlawing the sale of organs from both live and dead donors.

But in other parts of Europe -- including the former East Bloc countries and the former Soviet Union -- commerce in organs continued to thrive. In Germany, where roughly 7,000 people are on dialysis and only 2,000 to 3,000 a year are getting transplants, the market is big.

In one notorious 1988 case, a German company called the Association of Organ Donations and Mutual Human Substitution sifted through public bankruptcy notices to find prospective clients, then sent them a letter that read: "You're broke. You're a social leper, tainted with the legal and social equivalent of AIDS. The most horrid vultures will pursue you .... In case you don't have the guts for a life of crime, if your courage isn't up to a big break-in, a bank heist or a new life abroad, I offer you a solution founded on logic. Donate your kidney."

The founder of the company, Count Rainer Rene Adelmann von Adelmannsfelden, offered to pay up to $45,000 for kidneys and to arrange operations -- including doctor, donor and hospital fees for $85,000, taking a 10 percent cut for himself. Germany has no legislation on organ transplants, although the Cartel of German Transplantation Centers has adopted a code binding on all doctors performing transplants that says, "Any trade in organs ... is, in principle, excluded."

That has not stopped the nation's entrepreneurs from digging up new possibilities. Early last year, a German firm based in Berlin, Ona Trading Gmbh, started offering short trips to Moscow, where for roughIy $72,000 (or three times the price of a legal transplant in Germany) its clients could obtain a kidney. Ona Trading, in a letter to patients and their doctors, said it could arrange approximately 120 operations a year.

With the Commonwealth of Independent States in such disarray, the trade is continuing. Russian morgue officials and forensic medicine experts held a conference in Khabarovsk in September on ways to sell organs from dead bodies, including corneas and kidneys, for hard currency.

According to the German weekly newsmagazine Der Spiegel, doctors at the Charite Hospital in the East German section of Berlin used to remove organs from patients who had not been declared legally dead, giving them to party officials or selling them to the West for hard currency.

Citing records and testimony from staff members at the hospital, Der Spiegel said critically-ill patients were sometimes brought hundreds of miles to the hospital so they would be available for the transplants -- a practice that killed four such patients in 1988. And according to the German newspaper Bild Zeitung, the communist regime had arranged to have organs transplanted from political prisoners to faithful supporters of the Stasi, the East German security force.

Nor is Asia spared. Japanese suffering from kidney disorders are said to flock to Manila for transplants, while wealthy residents of Hong Kong and Singapore reportedly cross the Hong Kong border into Guangzhou in southern China.

According to Hong Kong doctors and human rights groups, an organization calling itself the Kidney Transplant Service Center has offered package tours to China for kidney transplants, and a prominent Hong Kong doctor told the British medical journal Lancet recently that customers pay about $20,000 for a kidney transplant.

But there have also been more sinister reports of transplants done at Nanfang Hospital in Guangzhou, in which prisoners were executed and their organs removed for sale to foreigners (at a going rate of $10,000 to $13,000) or high Chinese officials. The details were confirmed by a Chinese police official, who told the International League for Human Rights that "those who were executed would have their organs removed for transplant without prior consent or that of their families. For example, a colleague of mine who was going blind took the eyes of a prisoner who was executed. In order to preserve the eyes, the prisoner was shot in the heart rather than in the head. This is what happens. If they need the heart, the prisoner would be shot in the head instead."

When asked who would actually remove the organs, the police official said a doctor and a nurse would arrive in an ambulance. "Immediately after the execution, the coroner would examine the corpse and certify the death. The corpse would then be taken immediately inside the ambulance, where the necessary organs are removed. The corpse is then taken out of the ambulance and returned to the family. No one has seen the doctor or nurse, and no one is aware of the reason why they were there."

While the trade thrives in China, Hong Kong and the Philippines, it is also strong in the Middle East. The buyers come from oil-rich countries like Kuwait, where a 1987 decree made it illegal to buy or sell organs, and Saudi Arabia, where, according to the World Health Organization, it is "absolutely prohibited to buy or sell human organs." Those laws have sent a stream of buyers to Egypt, where kidneys are said to fetch up to $15,000. Cairo's six kidney transplant centers perform some 350 operations a year, with many of the donors coming from Sudan, Somalia or Ethiopia.

Egyptians themselves are technically not allowed to sell their kidneys to foreigners, but the trade goes on. In one recent incident, Cairo police arrested a textile worker, Ezzat Sawi, in January, charging him with robbing a jewelry store when his neighbors reported that he was suddenly spending huge amounts of money. According to the newspaper Al-Akhbar, police released the man after he produced documents proving he sold one of his kidneys for $6,000.

While a poor man can make a few thousand dollars, it's the middlemen -- the people who bring foreign buyers and sellers together -- who really profit. One such middleman, who agreed to talk anonymously about his business, met with Insight late one night on a side street on the outskirts of Cairo. A smooth-talking operator, fluent in English, French and Italian as well as his native Arabic, he wore expensive European clothes, chain-smoked Gauloise cigarettes and sat in the backseat of a gold Mercedes as he described some of the kidney transplants he had arranged.

"It's very simple, and it happens all the time," he says. "The first one was in 1987. 1 was working at the Sheraton el-Gezira, and there was a guest staying there, a Kuwaiti. He'd been asking around about finding someone who would sell their kidney, and I went up to see him. He was about 30. He said he'd made arrangements for the operation, but had to find a donor. And he said he'd pay $9,000.

"So I got in touch with my brother, who's a soldier in the Seqoa Oasis. He had a houseboy there, a bedouin. He was about 20, 1 think. He agreed to come up to Cairo, they did the blood tests, and they did the operation a few days later."

In all, he says, there were six persons involved: the seller, the donor, himself, the doctor and a couple of nurses. "The Kuwaiti paid $29,000 for everything. I got $7,000. The bedouin got $2,000, and the rest went to the doctor and the nurses. The Kuwaiti went back home, and about six months later I got a call from a friend of his, another guy who needed a kidney. It's a good business," he says, sitting back in the Mercedes and smiling.

If business is good in Egypt, it's even better in India. With its proximity to the Gulf states, widespread poverty, supply of trained transplant surgeons and no rules against live donor transplants, India is emerging as the largest and fastest-growing international kidney bazaar in the world. It's not known how many transplants are done in the major centers of Bombay, Calcutta and Madras, since a huge number of them are done in small, private clinics for cash, and no central registry is kept. But doctors in Delhi and Madras estimate that some 50,000 to 80,000 kidneys are needed by Indians alone, and many more operations are conducted on foreigners.

Only a few hours by plane from the Middle East, Bombay has become the undisputed capital of the trade. "In Bombay, foreigners make up a major part 54 percent of the recipients," says a government doctor in New Delhi. "The money is with the Arabs."

City hospitals such as Jaslok and Bombay Hospital were among the first to have dialysis machines and doctors trained to perform transplants, and the trade was strong but rather secretive during the 1970s. But as it became clear that doctors were taking home profits of 100,000 rupees (about $4,000) a month -- a fortune by Indian standards, and several times the average doctor's earnings -- more and more surgeons began to go into business for themselves. Throughout the 1980s, the trade flourished.

The business goes on quite openly, with patients coming in from other parts of India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Malaysia and, in some cases, Europe, as well as the Middle East. Doctors freely interact with kidney brokers, and there have been cases of surgeons paying finder's fees to other doctors for referring patients to them, according to the ethics team of the International Transplant Society.

According to Indian doctors and human rights activists, the process works like this: The person needing the kidney transplant will fly to Bombay and check into either a hospital or a private clinic with dialysis facilities, at a cost of roughly 1,800 rupees (about $72) a week. "Most of the operations are done in private clinics," says the government doctor. "In north Bombay there are about 40 'nursing homes,' which are basically private houses where transplants are done." The patient will then be tested for blood and tissue matching, which is key to the success of any transplant.

Once the patient has been tested, he is approached directly by a kidney broker, who generally has an informal partnership with the doctor doing the operation. Brokers find donors in the ranks of the poor, many of whom sell their blood to survive and are often eager to sell a kidney; blood donors get only about 30 rupees, or a little more than a dollar, for every bottle they give, while they can make 20,000 30,000 rupees ($800 to $1,200) for a kidney. Once the broker has found several potential donors with matching blood types, he'll take them to a laboratory to have the tissue matching done. When a match is found, the broker brings buyer and seller together and collects his fee, usually about 20,000 rupees.

While it sounds crass, Indian doctors merely shrug at the process. "Indian life depends on brokers," says one. "They get a commission and use it to bribe the right people. It's impossible to exist here without bribing." While there are many in the medical profession who decry the trade, others defend it and say that India should not be judged by standards in other countries.

"There are great inequalities in India," says an Indian transplant specialist in New Delhi. "One tends to treat the rich in a certain way, and the poor in another. The poor person who is dying of renal failure cannot be kept on in this country, because the cost of long-term treatment is beyond his means. So we concentrate on trying to save the lives of the rich."

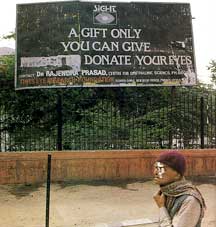

But a movement to outlaw the use of live donors is growing, led by a few doctors and the Kidney Foundation of India. Legislation has been under discussion in Parliament since last fall, but it looks unlikely to pass anytime soon, if ever. Still, a number of doctors insist that the trade is destructive to India, and the debate is heated; one doctor recently made the wild prediction that, if the current laws are not changed, half of India's population will be missing a kidney by the end of the century.

Others are more levelheaded. "I am opposed to the use of unrelated live donors,” wrote Dr. M. K. Mani, a nephrologist at the Apollo Hospital in Madras, in the February edition of the National Medical Journal of India. "Only the poor will make such a sacrifice for the sake of money, and only the rich can afford to buy The poor are less educated and cannot comprehend the risks involved." Contacted at the hospital, Mani refused to comment further, saying only, "This is an Indian problem, and we will solve it ourselves."

But there are other doctors who defend people's right to sell their kidneys, saying it gives the poor an opportunity to get the money to build a home, raise a dowry, start a business or get out of debt money that they would otherwise be unable to obtain. Moreover, they say, paying donors allows more people to live who otherwise would die. They've even developed a euphemism for the business. "We don't like to call it 'selling,' " says Dr. Salim J. Thomas, one of four kidney transplant surgeons at the private Pandalai Clinic in Madras. "We call it 'rewarded gifting.' "

After Meenakshi sold a kidney, her life just got worseLike several hundred of the 5,000 residents of Villivakkam, a slum on the outskirts of Madras, 32-year-old Meenakshi (the villagers go by only one name) knows the Pandalai Clinic well. Outside the cramped, airless mud hut that she lives in with her husband and four children, she tells how a middleman approached them three years ago and offered to pay her husband 20,000 rupees for one of his kidneys.

"I didn't want him to do it,' she says. "I knew it was dangerous, and that he wouldn't be able to work, no matter what they said. But we were in debt, and he wasn't working."

Unwilling to let her husband be operated on, she let the middleman take her to the Pandalai Clinic for testing, and a month later she was operated on at the Guest Hospital on Poonamallee High Road in Madras. Eleven days after the operation, she was allowed to go home.

Since then, she says, her life has been ruined. She can't work without suffering abdominal pains, and like other Villivakkam donors, says she tires easily. The money she earned went quickly to pay debts.

"The problems didn't end, they just got worse," she says. The crowning blow came last year, when her husband, again out of work, sold one of his kidneys as well, without telling his wife.

Meenakshi's story is only one of hundreds in Villivakkam, which has become known in Madras as “the kidney colony” for the number of people there who bear the scars of their “rewarded gifting.” Its residents say there are 300 documented donors in the village and probably another 200 or 300 who have kept their operations secret. In fact, says one villager, Villivakkam has been "farmed out” and the trade has moved to other slums around Madras -- Ayanavaram, Korattui and Ambatur.

But in the Pandalai Clinic, Dr. Thomas defends his work vigorously. They've stopped using middlemen, he says, so all the money goes to the donor. "Donors come here on their own, by word of mouth,” he says. "And it's not just the destitute who come, because the really destitute are not suitable -- they're usually not healthy. Our donors mostly come from the lower middle class, small shopkeepers who need money to meet a family obligation and have no way to get it. They may need to get money for a daughter's dowry, or to pay for a sickness in the family. Some get their businesses out of trouble."

Surgeon Thomas (r) with a kidney recipient. In fact, says Thomas, potential donors are screened not just medically, but by social workers and psychologists as well. “We test for hepatitis, and 5 to 10 percent are weeded out on those grounds. Another 5 percent are weeded out on social grounds," he says. The ones who are found fit are then tested for tissue matching at another hospital, and ultimately matched with a recipient. "We have about 60 donors waiting at any given time,” he says. "And a waiting list of about 50 recipients."

Thomas, Dr. K. C. Reddy and the other two surgeons on the team perform 16 renal transplants a month at the nearby Guest Hospital. They work simultaneously in adjoining operating theaters, two on the donor and two on the recipient. The kidney is removed, cleaned, cooled and transferred within 25 minutes. They limit the number of foreign recipients to two per month.

"We have a number of patients from the littoral countries around the Indian Ocean: Bangladesh, Nepal, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Singapore, the Maldives. But foreigners come here sometimes and find they have to wait for months and months,” Thomas says, shrugging. "So they go to Bombay; it's not difficult to find out where it can be done quickly there."

While the donors of Villivakkam are not paid much for their organs, they make out better than some others – who have literally been robbed of them. In one notorious case that sparked debate as high as the Indian Parliament this year, there was apparently a theft of a kidney at Nanavati Hospital in Bombay several years ago. Although accounts differ and the facts have yet to be sorted out, a resident of Bombay, Sanaullah Khan, claims that when he went to a hospital complaining of stomach pains he was approached by a man who told him he could have his problems cured for free if he went for a blood test at a particular clinic in the city.

The man, who went by the name of Govind, registered the 19-year-old Khan under a false name and a few weeks later took the youth to Nanavati Hospital, where he was given an anesthetic. Later, Khan told police, he woke up in a recovery room, with a nurse telling him that his stomach problems had been fixed. Ten days later he was discharged, with reports from the hospital showing that he had been suffering from blood clotting problems.

Suspicious, Khan's family took him to another hospital, where it was discovered that his left kidney had been removed. Khan went to the police.

Debate is still going on between some members of Parliament, who want racketeering charges brought against the doctors involved, and India's health minister, who says Khan willingly sold his kidney for 30,000 rupees.

Other reports of organ thefts have surfaced. In an astonishing case earlier this year, the Indian Supreme Court moved to restrain the Central Jalma Institute for Leprosy in Agra from removing organs from patients after allegations that institute officials had lured lepers from different parts of India with promises of free health care, then removed their eyes and kidneys for resale.

According to the allegations (which have yet to be proved but are thought to be true by a government official close to the case), doctors at the institute's hospital told the patients they needed to have some of their organs removed to prevent the spread of the disease. The government says 21 patients were operated on and their organs sold to wealthy buyers; the lepers were then given a little money and sent home.

Even when buyers get healthy kidneys, complications often set in. There have been reports of cases where doctors botched operations, the patients died, and the clinics issued reports saying that the patients had been discharged against medical advice.

"Anything can happen in India," says a physician in Bombay. "Unlike in America, there is no way to get legal redress -- it's very difficult to sue a doctor."

A team of doctors who studied 130 West Asian patients who had kidney transplants in Bombay reported "unusually high" rates of mortality; at least 25 died after returning home and four contracted the virus that causes AIDS. Bacterial and viral infections were common, said the doctors, because patients had been overdosed with the immunosuppressant drug cyclosporine in order to match incompatible tissues.

Moreover, middlemen get many of their donors from the ranks of blood donors, who tend to be malnourished, alcoholic and diseased. And while the middlemen can't alter the essential blood typing, they can and do pay off blood testers to ignore evidence of malaria, jaundice or other diseases. And less than 20 percent of the blood in India is tested for HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, according to a surgeon in Delhi.

"They say they test for HIV, but they don't,” he says. “They don't even test for hepatitis B. It just shows you that you can enact any law, but the enforcement is very different."

A study by Kuwait City's Hamed al-Essa Organ Transplant Center of 59 Kuwaitis who had gone to Bombay or Madras for the operation found that the operations were often done in badly equipped private clinics, with poorly trained staff. Six of the patients they studied died shortly after the operation, either in India or after returning to Kuwait; one even died on the plane home. Many arrived home with bleeding wounds, serious surgical complications and diseases such as AIDS, malaria, hepatitis B or tuberculosis.

One patient received a diseased kidney that had to be taken out; another, complaining of abdominal pains, was found to have a set of surgical scissors still inside him.

Despite the horrors of the trade, it has become so entrenched and so lucrative that new laws in India, even if enacted, probably will not have much impact. There have been international efforts to wipe out the trade since 1970, but without a global agreement and tough enforcement it's likely to continue.

"You're not going to be able to solve the problem if there are weak links," says Richard Lillich, a law professor at the University of Virginia who has studied the problem extensively. "You've got to have some uniform obligation on the international plane, implemented by every country. The trend is in that direction, but there's still no overarching international convention.”

(Insight Magazine, June 8, 1992)

***

(For more information on this topic, see the website "Organ Selling." )

References (7)

-

Response: colon cleanserThe colon is a very important part of the body in that it is in part, responsible for the elimination of waste in the form of feces. It functions in the capacity of re- absorption of food nutrients and water. However, it is possible for the colon to be unable to ...

Response: colon cleanserThe colon is a very important part of the body in that it is in part, responsible for the elimination of waste in the form of feces. It functions in the capacity of re- absorption of food nutrients and water. However, it is possible for the colon to be unable to ... -

Response: 12 BEST HOME REMEDIES FOR KIDNEY STONES12 BEST HOME REMEDIES FOR KIDNEY STONES

Response: 12 BEST HOME REMEDIES FOR KIDNEY STONES12 BEST HOME REMEDIES FOR KIDNEY STONES -

Response: women sarees online

Response: women sarees online -

-

Response: kidney dialysis

Response: kidney dialysis -

Are you looking for a general physician for treatment? You have come to the right place. At Medrec hospital, you will find the best general physician near you.

Are you looking for a general physician for treatment? You have come to the right place. At Medrec hospital, you will find the best general physician near you. -

Response: Export Import Data

Response: Export Import Data

Reader Comments