Haiti: Nearing the Point of No Return?

By Stephen Brookes in Port-au-Prince

for Insight Magazine

When paramilitary thugs gunned down Justice Minister Guy Malary outside his office Oct. 14, to many Haitians it was a body blow to the country's fragile return to democracy. Coming only hours after President Clinton had warned the U.S. was prepared to act "unilaterally" to enforce a U.N.-brokered accord to bring ousted President Jean-Bertrand Aristide back to power, the assassination was a blunt statement by the military and police leaders who rule the country that they have no intention of stepping aside.

Photos by Rick KozakThe assassination threw the country into turmoil, prompting the United Nations to withdraw most of its remaining personnel and to impose an embargo on the country, backed up by warships.

Clinton is pondering further diplomatic responses, but there appears to be little the international community. And while Washington is still officially optimistic that democracy can be restored to Haiti, few observers inside or outside the country believe Aristide can resume office, as planned, on Oct. 30 -- or possibly ever.

Has Haiti passed the point of no return? The carefully constructed agreement signed this past July 3 -- under which Aristide would be reinstated, the coup leaders removed and the military restructured -- is in tatters; the interim government under Prime Minister Robert Malval is on the verge of collapse; and the military, the police and their loose army of civilian thugs known as "attaches" are in unquestioned control of the country. The military seems prepared to weather the U.N. embargo, and outside intervention seems increasingly unlikely. Joseph Michel Francois, the powerful police chief in Port-au-Prince who is thought to hold the real reins of power in Haiti, seems ready to take the country down with him if he has to, and his followers have vowed to create "another Somalia" if U.S. troops return. "I'm Haitian," Francois told a local radio station on Oct. 14, "and I've chosen to die in my Country."

Hopes that the country could return peacefully to democracy were running high this past summer, when Aristide and Raoul Cedras, the general who deposed him in September 1991 coup, signed a set of accords on Governors Island in New York. Under the agreement, Cedras and other high military figures would leave their posts and allow Aristide to assemble a government and assume the presidency by Oct. 30; in return, the U.N. would lift the oil embargo it had imposed in June, which was crippling the country's economy. There would be a general amnesty for participants in the coup, and U.N. forces would be brought in to help separate the military from the police and "retrain" them in the fine art of responding to civilian rule.

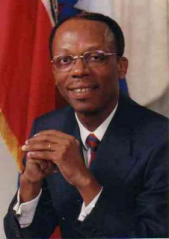

Jean-Bertrand AristideBut even before the ink was dry, there were signs of trouble. The antagonism between Cedras and Aristide was so intense that the two never even met during the talks; they signed the agreement 12 hours apart. Aristide was able to set up a new government in late August with Malval, a publisher, as his prime minister, but tensions were so high by then in Haiti that Malval's swearing-in was held in Washington. And while the Parliament approved the new government, it did so for one reason only: "We didn't vote for Malval," says Antoine Joseph, leader of the Chamber of Deputies, the lower legislative house, and an opponent of Aristide. "We voted to end the embargo."

Political tension fed a rising climate of violence. Gunfire, not heard since the coup, was becoming a nightly phenomenon. "The trend started in July, about the time the Governors Island agreement was signed," says Ian Martin, director of human rights for the U.N. International Civilian Mission in Port-au-Prince. "There have been more than a 100 killings since then -- about 60 in September alone. And the violence is carried on with no attempt by the police to interfere." When Izmery, a key financial supporter of Aristide, was dragged out of a crowded church in mid-September and murdered execution-style by paramilitary thugs, it appeared that the agreement might rapidly unravel.

If it wasn't already clear, the murder of Izmery made it plain that violence was tolerated, if not directly controlled, by the military and the police -- and that it was designed to undermine Aristide's return. "By keeping people in a state of fear, the military could claim that Malval wasn't capable of running the country and maintaining peace," says one Western diplomat. "That would open the door for them to say, 'Haiti needs the military to restore order."

Rule by the gun, of course, is nothing new in Haiti, and installing a democratic regime there may be impossible, even with the most skillful diplomacy. Almost three decades of rule under the Duvalier family destroyed nearly all the institutions that might have been used to build an open democracy, and the country has a long history of despotism and violence. Both Francois "Papa Doc" Duvalier, the self-proclaimed "president of life," who came to power in 1957, and his son and successor Jean-Claude, known as "Baby Doc," who ruled until 1986, used a private militia of thugs known as Tontons Macoutes to keep Haitians terrorized; many are still around, reincarnated as police or attaches.

Moreover, the few democratic elements that exist are fragile. The party system is in its infancy; while there are almost two dozen political groups, the four main parties vie for power in a squabbling and ineffectual Parliament. The courts are virtually powerless, and the religious community is divided. The only institution of any real power is the military.

"We're trying to inaugurate democracy here," says Dante Caputo, the former Argentine foreign minister who now leads the U.N.'s mission to Haiti. "But it's a difficult situation -- we have to start bringing together institutions that are weak and have never known life under democracy." "Difficult" may be putting it mildly. Fully 75 percent of the country's 6.5 million people are illiterate, and the poverty is overwhelming -- Haiti is the poorest country in the Western hemisphere, and much of the educated middle class has fled abroad.

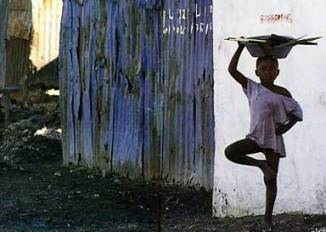

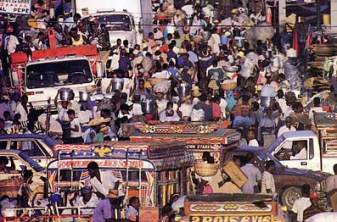

In the slum of Cite SoleilWhat's left behind is largely in ruins. The roads that wind through Port-au-Prince are riddled with potholes and run with sewage, and piles of rotting garbage overflow the narrow sidewalks. The streets of the capital are crowded with vendors hawking fruits, plastic jugs, wood carvings - anything cheap that sells. Prostitution and drugs are ubiquitous, and poverty is so rife that even the tombs in the city's central graveyard have been broken into and looted for jewelry buried with the dead -- or for the brass handles on the coffins. The T-shirt factories that line the road out to the airport are idle; there are no customers since the embargo, and electricity is spotty anyway. Even the windows are the foreign affairs and commerce ministries are boarded up; weeds grown on the grounds outside. At night, the streets are dark and empty. The city gives the impression of having been abandoned and left to die.

But of course, it hasn't; it's constantly patrolled by thousands of police and military attaches. There are thought to be as many as 5,000 of the attaches, armed by the police and given a few dollars a week as pay -- as well as license, quite literally, to steal. They're everywhere in Port-au-Prince, muttering into walkie-talkies and cruising the streets in their signature blue Toyota pickups -- some sporting bumper stickers that read: "Haiti -- Love It or Leave It."

But perhaps the most fundamental obstacle to peace in Haiti is the gulf between rich and poor. While most of the country swelters in the slums, working -- when there is work -- for wages of about 14 cents an hour, Haiti's elite inhibits the lavish suburbs on the hillsides around Port-au-Prince; most back the military government, and many are the beneficiaries of lucrative government contracts. Bridging the gap takes political skill -- skill that was beyond Aristide during his seven months in office.

While Aristide has been embraced as a symbol of democracy in the West, to much of Haiti's powerful elite he represents exactly the opposite. A physically slight but charismatic priest who rose to prominence in the 1980s through his populist sermons, Aristide enjoys near-cult status in the slums of the Port-au-Prince and in the rural countryside. But his Marxist rhetoric and die-hard opposition to the rich, while winning him the presidency in 1990 with an astonishing 67 percent of the popular vote, soon undermined his own effectiveness.

Raised as a Salesian Roman Catholic, Aristide was kicked out of the order for allegedly fomenting class violence, and his sermons inspired two assassination attempts against him in 1987 and 1988. After he was elected, he quickly alienated potential supporters; admitting that he was neither a politician nor an economist, Aristide failed to win over the business class or build a political coalition in the Parliament, relying instead on the mass support he got from the popular movement called Lavalas.

But that wasn't enough to sustain him in power, and a series of missteps soon followed that were to lead to his downfall. While effectively fighting to end corruption in the government, he made at least two demagogic speeches in which he praised Pere Lebrun -- a slang term for the flaming tires that his supporters hung around the necks of his opponents to kill them -- raising fears that Aristide was encouraging violence and retribution. He was soon accused of violating constitutional rights, and his support began to crumble.

"For the military, Aristide was a dictator," says one Haitian observer. "As far as the army is concerned, they didn't mount a coup d'etat -- they restored democracy."

The Haitian elite agreed. "Aristide is a priest, the head of a parish," says a professional in Port-au-Prince. "If you're not part of his parish, you don't get his sacrament. He has the support of three-quarters of the Haitian people, but he needs the support of that other quarter, because they're strong enough to create unrest -- and they'll always hate him."

Moreover, Aristide's relations with the West have been uneven at best. His rhetoric from the pulpit was anti-capitalist, nationalistic and often anti-American, and he was known to have "nervous attacks"; a CIA report submitted to the Bush administration characterized Aristide as "unstable."

Some observers say, however, that his two years in exile have sobered him up to political realities. "Aristide has learned a lot in two years," says Stanley Schrager, spokesman for the U.S. Embassy in Haiti. "He's been exposed to American views, and he realizes he's got to change."

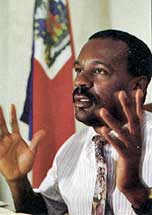

Prime Minister Robert MalvalHe may not have the chance. If Aristide can return to power, he'll be working with the fledgling and tenuous government of Malval, who is well-liked by the international community but not nearly as popular in the slums of Port-au-Prince. One of the few members of the elite class who supports Aristide, the prime minister has a reputation for intelligence and honesty. "Malval is a rock of steadiness," says Schrager. "He's differed publicly from Aristide on a number of occasions, and deplored extremism."

But Malval has been unable to get his government up and running, to stop political assassinations or to disarm the attaches; in fact, he's virtually powerless. Malval and most of his 11 remaining Cabinet members have to work out of his suburban home -- partly because military-backed officials have not yielded him the presidential palace, and partly because most government offices have been looted of telephones, fax machines, even chairs. The bureaucracies are bankrupt, bled dry by endemic graft and other corruption, and the payrolls of every office are bloated with "zombies" -- unnecessary workers who are friends or family members of the military -- and "phantoms," who exist only on paper. Corruption is thought to take as much as 90 percent of what the government spends.

Moreover, Malval has had to contend with direct physical attacks on his government, culminating with the murder of the justice minister. More than 100 protesters broke into the foreign ministry as Malval was trying to install Claudette Werleigh as the new minister of foreign affairs, and the finance ministry and burgled twice in September. And on Sept. 8, when Evans Paul, the mayor of Port-au-Prince, reclaimed City Hall from the attaches who have been occupying the building, five people were killed and 31 injured in the melee that erupted. "Malval has no control of the political situation," says Joseph, the leader of the Chamber of Deputies.

Indeed, Malval faces substantial opposition in the Parliament, where he's generally supported in the 17-member Senate and opposed in the 79-member Chamber of Deputies. Aristide needs the support of both houses to return; he can't proceed with the all-important reform of the military without Parliament's consent. But opposition to the plan is so intense that the body has been unable even to vote on it.

Aristide and Malval also alienated potential political supporters by forming a narrow government. "There are four main groups in the Parliament: the Social Democrats, the Liberals, the Nationalists and the Christian Democrats," says Joseph. "Of those, only the Nationalists are represented in Malval's government -- and the Lavalas people. So he can't expect to have wide support."

But Aristide's supporters angrily insist that calls for a broadly representative government are mostly hot air. "It's a myth to talk about an idealistic kind of government that will include everyone in the country," fumes Firmin Jean-Louis, the president of the Senate. "In Haiti, terms like 'conciliation' are used as blackmail; they say, 'If you don't include us, we'll make trouble."

And in a country where the Roman Catholic Church wields important influence, the Haitian National Bishops Conference has distanced itself from Aristide. "The Bishop's Conference has done everything possible to obstruct Aristide from becoming president," says Pere Hugo, a Belgian priest who has been in Haiti for 30 years. "The bishops never condemned the coup and called the Organization of American States 'criminals' for imposing the embargo."

Senate president Jean-Louis

Moreover, some of Aristide's most notorious opponents have been returning to Haiti from exile. Former post-Duvalier dictator Prosper Avril is back, as is Franck Roumain, the former mayor of Port-au-Prince who is thought to have masterminded a 1988 attack on Aristide's church, in which 12 people were killed. And Jean-Claude Duvalier's supporters say even Baby Doc himself may return from France, where he's been since 1986.

"I'm extremely pessimistic," says a Haitian political analyst, a member of the foreign-educated elite. "The international community stood by Aristide, but his opponents won't play the game. They can create a state of unrest that will make it impossible to rule. The U.N. gave Aristide an embargo from the outside, but his opponents can give him one from the inside. And so much hate has built up in this country over the past two years that reconciliation may be impossible -- they'd rather destroy the country than surrender."

Recent months have seen the birth of nationalistic and right-wing political groups, including the Resistance Committee to Defend National Sovereignty and the Front for the Advancement and Progress of Haiti, or FRAPH, which claims to represent several dozen organizations and is thought to express the political views of the military. It's also an unofficial base for the attaches, according to knowledgeable Haitian sources.

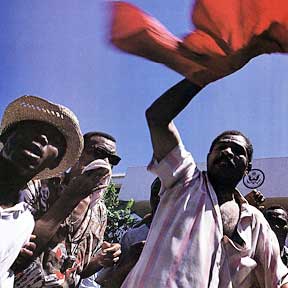

At now-weekly rallies, FRAPH manages to organize hundreds or even thousands of supporters to protest Aristide and what they see as the interference of the international community in Haitian affairs. In one recent protest, the crowd waved red scarves, the trademark of the old Tontons Macoutes, and shouted anti-Aristide and anti-U.N. slogans, while marching past the U.S. Embassy, as a white Nissan pickup truck loaded with blue-shirted, gun-toting police watched passively. "Aristide's a communist pig," shouted one marcher. "He killed people, set them on fire, broke into houses, destroyed factories! The seven months Aristide was president destroyed the country! And if he comes back here, we'll eat him! We'll eat him with bananas!"

While one U.N. analyst in Haiti dismissed the group only a few weeks ago as "a little neo-Duvalierist grouplet," it's become a force to be reckoned with. FRAPH leader Jean-Julot Chamblain told the local Radio Metropole in early October: "We want Malval to go. If he does not, we will force him to go."

And they may be able to. Haitian sources say it was FRAPH members who beat up journalists and threatened U.S. Charge d'Affaires Vicki Huddleston on Oct. 12, when the USS Harlan County was not allowed to dock in Port-au-Prince. The group has successfully called for general strikes in Port-au-Prince in recent weeks (gaining cooperation by spraying downtown markets with machine-gun fire).

"There will be civil war if Aristide comes back," warns a man in a black hat and sunglasses outside FRAPH's headquarters by the Champ de Mars park, a few blocks from the National Palace. "Since he left, there haven't been tires burning in the streets. But if he comes back, there will be tires burning -- lots of tires burning. If Aristide comes back, he better carry a gun."

While FRAPH's funding and organization remain shadowy, Haitian analysts say the group is tied to the military and responds to the orders of Gen. Cedras, the commander of the 7,000-man Haitian army and the effective leader of the country. A soft-spoken man who's seen as politically moderate (he is thought to have participated only reluctantly in the coup), Cedars runs an army that is untrained, poorly equipped and corrupt. High-level officers are reputedly involved in gun-running, petty racketeering, and drugs; one officer, Col. Jean-Claude Paul, was indicted in the U.S. on cocaine-smuggling charges before dying under suspicious circumstances in 1988.

Antoine JosephAlmost to a man, the military is dead-set against Aristide's return and resents the U.N. presence -- in part because members of the military don't want to lose the money they get from smuggling and other activities, and in part because of ideology.

"The army's a problem in this country," says Joseph. "It was set up like others in Latin America -- to fight communism. And the situation is the same in the minds of many in the army. They see that communism is dead abroad -- but here they see Aristide."

The ties between the attaches and the military are clear. The U.N.'s Martin says, "People putting up Aristide posters are liable to arrest, and there have been beatings and torture against those arrested for political and even ordinary crimes. Who's doing this? It's the armed forces, attaches linked to the armed forces and in rural areas it's the chefs de section and their assistants.

"After the Izmery killing, pressure was brought on the military, and the killings went down for a while. That suggests that if the armed forces choose to, they can control the level of violence. And there is credible testimony that the activity of some of the attaches is directly linked to Michel Francois."

While international attention has been focused largely on Cedras, the shadowy figure of Police Chief Francois may wield even more influence. A taciturn man who rarely gives interviews and refuses to be photographed, the 36-year-old Francois is widely thought to be the leading force behind the 1991 coup. As head of a 1,000-man force, Francois is thought to control the state-run media and to be profiting from the national cement industry. And many Haitians see him as the last, and most stalwart, bulwark against Aristide.

"I'm not alone -- there are many people who identify with Michel Francois," he said in an interview with the Haitian paper Le Nouvelliste on Sept. 23. "When my life is in danger, I'm capable of doing anything." And when asked if his men would allow him to leave, he responded in English, "That is the question."

"The key to Haiti's crisis is Michel Francois," says Joseph of the Chamber of Deputies. "But even if you remove him from the police force, you'll have to find jobs for all the other police--because they'll be dangerous."

Both Aristide and U.N. envoy Caputo have linked Francois directly with the attaches, going so far as to label him a killer. Francois denies the links, saying that with more than 17,000 registered guns in the city, Port-au-Prince is swarming with armed groups over which he has no control. Nevertheless, it was widely reported that, before and after the slaying of Izmery at Sacre Coeur Church in September, police drove by and did nothing to intervene.

While the military and police maintain their monopoly on force, support remains high for Aristide in the sprawling, fetid slums in and around Port-au-Prince. "We're waiting for him to come back. There's no one else for us," says a young man crouched outside a tin-walled hut in Cite Soleil, a tangle of alleys and open sewers in northern Port-au-Prince.

But few are willing to risk their necks against the attaches. Aristide has called for the establishment of neighborhood vigilante committees, and many already exist; most of the shantytowns have established "brigades" to guard against the shootings and robbery that go on every night.

In the narrow, twisting paths that run through the shantytown of Carrefour Feuilles, on the hillside that runs up the southeastern edge of the city, young men gather every night to watch for the approach of the attaches. It's a warren of unpaved alleys and dark culs-de-sac patrolled by Aristide supporters with rocks and machetes. There's not a lot the brigades can do against machine guns. Nevertheless, says one member, they have certain advantages.

"This is dangerous territory for the attaches," says Jean, a wiry man in his early 20s who leads a 50-man brigade. "We don't walk in the streets; the attaches have guns, and we don't. But we know the area. At night, we'll get together; a few people on one corner, 10 on another, 10 on another, and we keep our eyes open. The attaches send spies up -- guys who know the area. But we know who they are."

But little chance remains of a full-scale civil war or a popular uprising. Most of the poor cling to the unlikely hope that the international community will intervene militarily.

"The U.N. is no good if it's an intervention for nothing, if there's no fighting," says Jean. "But if it's to fight the attaches, then it's okay. And reforming the police won't happen unless the U.S. comes in, because the Duvalierists want to keep the country the way it is. But Michel Francois can act brave because he knows the Americans are just joking with him."

Under such circumstances, can Aristide ever return? Clinton has said that the Haitian military would be "sadly misguided" to think that the U.S. would abandon its effort to restore democracy, but the success of the embargo, the freeze on Haitian assets abroad and the naval blockade imposed by the U.N. remains to be seen. The last embargo was leaky, with at least a dozen countries in Europe, South America and Africa routinely ignoring it, and the elite seem to be able to get what they need. The military is thought to have stockpiled a year's supply of oil and appears ready to resist to the end, and it is playing up its role as defender of national sovereignty; as the USS Harlan Country lay helpless at anchor on Oct. 12, unable to dock because of protesters, Cedras made a show of laying flowers at a statue of Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who saved the country from an invading French force in 1804 and won the country's independence.

Under such circumstances, can Aristide ever return? Clinton has said that the Haitian military would be "sadly misguided" to think that the U.S. would abandon its effort to restore democracy, but the success of the embargo, the freeze on Haitian assets abroad and the naval blockade imposed by the U.N. remains to be seen. The last embargo was leaky, with at least a dozen countries in Europe, South America and Africa routinely ignoring it, and the elite seem to be able to get what they need. The military is thought to have stockpiled a year's supply of oil and appears ready to resist to the end, and it is playing up its role as defender of national sovereignty; as the USS Harlan Country lay helpless at anchor on Oct. 12, unable to dock because of protesters, Cedras made a show of laying flowers at a statue of Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who saved the country from an invading French force in 1804 and won the country's independence.

Aristide's supporters generally welcome the embargo. "The support of the U.N. and the U.S. is indispensable to us to get control over the country's says Senate leader Jean-Louis. But even if it works, there may be a backlash. According to the Haitian political analysts, "Most people see the U.N. as an intervention force. No one in Haiti forgets that we were occupied by the United States for 19 years -- and if Aristide comes back, he will have been imposed on us by the blockade." And even among his supporters, Aristide could be seen as a puppet of the American power that he used to decry in his sermons as "imperialistic."

Joseph says, "When Aristide was in power, he had problems dealing with Parliament, with the police, with the Catholic Church and with the private sector -- and when you have problems like that, you lose your power to govern. So there was a coup d'etat. Now, I'm not in favor of a coup -- it's not constitutional. But there are still a lot of sector opposed to Aristide. And there are even more problems than before."

But to most observers, discussion of Aristide's political skills is moot -- they expect the situation to be resolved as it has been so often in Haiti's violent past. "It won't happen at the airport; we're a polite and well-mannered people," says a member of Haiti's professional class, with an ironic smile. "But he'll be slaughtered eventually. It's almost guaranteed. He'll be a sitting duck."

(Insight Magazine, November 8, 1993)

References (10)

-

Response: Новые окнаДом Окна

Response: Новые окнаДом Окна -

Response: lights for living room

Response: lights for living room -

Response: happy new year 2017

Response: happy new year 2017 -

Response: https://goo.gl/xizLEU

Response: https://goo.gl/xizLEU -

Response: 4 X Anti Corona Door Handle Tools

Response: 4 X Anti Corona Door Handle Tools -

Response: Veterans Day Images freeVeterans Day Images. Sharing Happy Veterans Day Pics & Wallpapers are the Best way to celebrate and download Images with Quotes through veterans day photos.

Response: Veterans Day Images freeVeterans Day Images. Sharing Happy Veterans Day Pics & Wallpapers are the Best way to celebrate and download Images with Quotes through veterans day photos. -

Response: Thanksgiving Good Morning ImagesHappyThanksgivingQuotes offers Good Morning Happy Thanksgiving pictures 2022. quotes, photos, wishes & images, to be used on Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, Whatsapp, Twitter, Tumblr etc!

Response: Thanksgiving Good Morning ImagesHappyThanksgivingQuotes offers Good Morning Happy Thanksgiving pictures 2022. quotes, photos, wishes & images, to be used on Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, Whatsapp, Twitter, Tumblr etc! -

Response: Kft eladás hogyan

Response: Kft eladás hogyan -

Response: cégeladás és cégátadás

Response: cégeladás és cégátadás -

Response: why is my outlook stuckstephen brookes - international - Haiti: Nearing the Point of No Return?

Response: why is my outlook stuckstephen brookes - international - Haiti: Nearing the Point of No Return?

Reader Comments