Kalichstein-Laredo-Robinson Trio at the Terrace Theater

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • May 1, 2013

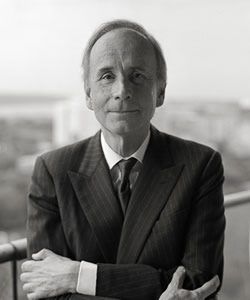

It’s tough being a composer in the 21st century. How do you satisfy those omnivorous modern ears out there, those audiences at home with everything from Monteverdi to Willie Nelson to Tuvan throat-singing? Ask Stanley Silverman. He’s nothing if not wide-ranging — the guy once brought Pierre Boulez to a party thrown by Paul Simon -- and his wildly eclectic Piano Trio No. 2 was the centerpiece of a concert at the Kennedy Center’s Terrace Theater on Monday night by the illustrious Kalichstein-Laredo-Robinson Trio. Stanley SilvermanThe KLR players are superstars of the chamber music world, and from the first notes of the evening it was clear why. Opening with Beethoven’s not-too-serious Piano Trio in B-Flat Major, Op. 11 — an entertaining work whose main claim to fame is its variations on a popular song of the time — the trio gave it a rich and comfortably unbuttoned reading, a little ragged around the edges here and there (pianist Joseph Kalichstein seemed to have just taken his fingers out of the fridge) but full of vitality and playful humor.

Stanley SilvermanThe KLR players are superstars of the chamber music world, and from the first notes of the evening it was clear why. Opening with Beethoven’s not-too-serious Piano Trio in B-Flat Major, Op. 11 — an entertaining work whose main claim to fame is its variations on a popular song of the time — the trio gave it a rich and comfortably unbuttoned reading, a little ragged around the edges here and there (pianist Joseph Kalichstein seemed to have just taken his fingers out of the fridge) but full of vitality and playful humor.

But the Beethoven was merely a prelude to Silverman’s work, which received its Washington premiere. The Piano Trio No. 2, “Reveille,” caroms freely among styles: A spiky modernist opening softens into an ethereal melody, which warps into a sensuous Cuban Guajira, which transforms into a classical fugue while Renaissance dances drift hither and yon, until the whole thing bursts into an anything-goes riff on Paul Simon’s “You Can Call Me Al.” It’s sort of a hot mess — Silverman himself says the piece “is not intended to ‘hang together’ any more than life itself,” and, fair enough, it doesn’t. But imaginative writing, a complete lack of stuffiness and a hugely enthusiastic reading by the KLR players (for whom it was written) made up for the kitchen-sink feeling, and it proved to be an engaging — if sometimes head-scratching — listen.

As for Brahms’s Piano Trio No. 1 in B major, Op. 8, which closed the program, there is only one thing to say: If you missed this performance, you should regret it bitterly for the rest of your life. It’s a ravishing work, an epic masterpiece by the young and unfathomably mature Brahms (he was 20 when he wrote it), and it would be hard to imagine a more passionate, perfectly controlled and absolutely radiant reading than it received from the KLR players.

Keller Quartet at the Library of Congress

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • April 19, 2013

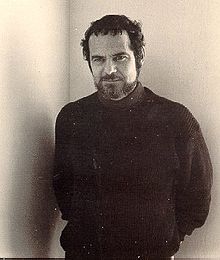

The Library of Congress is known for its provocative concert series, but Thursday night’s performance by the Keller String Quartet — a world-class outfit from Hungary with a gorgeous, hall-filling sound — may have been one of the most intriguing of the season. Focusing on three monumental but intensely personal Russian quartets, the Keller showed just how intimately entwined the pieces were with one another, and with the vast cultural consciousness they share. But this wasn’t some academic exercise in music history — it seemed to throw open a window into the composing mind itself. Alfred SchnittkeThe evening opened boldly with the strange and almost hallucinatory String Quartet No. 3 by Alfred Schnittke. German-born but Russian to his bones, Schnittke delighted in laying bare his musical roots, drawing freely on other composers in his own protean and fiercely original work. And true to form, the quartet’s opening eight bars contain no less than a quote from a Stabat Mater by Lassus, the theme from Beethoven’s monumental Grosse Fuge Op. 133 and the four notes that Shostakovich used as a musical “signature” in his own works — all of which crash and slide and transform into each other with passionate imagination over the next 20 minutes. That may sound gimmicky, but there’s nothing superficial in Schnittke’s quartet, no hint of cheap pastiche: It’s an exploration of musical identity and a work of exhilarating depth and power.

Alfred SchnittkeThe evening opened boldly with the strange and almost hallucinatory String Quartet No. 3 by Alfred Schnittke. German-born but Russian to his bones, Schnittke delighted in laying bare his musical roots, drawing freely on other composers in his own protean and fiercely original work. And true to form, the quartet’s opening eight bars contain no less than a quote from a Stabat Mater by Lassus, the theme from Beethoven’s monumental Grosse Fuge Op. 133 and the four notes that Shostakovich used as a musical “signature” in his own works — all of which crash and slide and transform into each other with passionate imagination over the next 20 minutes. That may sound gimmicky, but there’s nothing superficial in Schnittke’s quartet, no hint of cheap pastiche: It’s an exploration of musical identity and a work of exhilarating depth and power. Dimitri ShostakovichPart of that power came from the Keller players themselves, who brought such intensity to the work that it prompted a standing ovation. They followed with an equally weighty work, Shostakovich’s Quartet No. 8 in C minor, Op. 110. One of the most personal, pathos-filled and impossible-to-forget works of the 20th century, it’s a masterpiece of anguish, terror (a barely suppressed shriek seems to run through it) and, ultimately, hope. It needs a delicate balance of compassion and feral bite to make it work, and the Keller brought it off to snarling perfection.

Dimitri ShostakovichPart of that power came from the Keller players themselves, who brought such intensity to the work that it prompted a standing ovation. They followed with an equally weighty work, Shostakovich’s Quartet No. 8 in C minor, Op. 110. One of the most personal, pathos-filled and impossible-to-forget works of the 20th century, it’s a masterpiece of anguish, terror (a barely suppressed shriek seems to run through it) and, ultimately, hope. It needs a delicate balance of compassion and feral bite to make it work, and the Keller brought it off to snarling perfection.

As if to counterbalance all that 20th-century angst, the evening ended with Tchaikovsky’s sweeping Quartet No. 1 in D, Op. 11. It’s a heart-gladdening thing, full of soaring lyricism and ecstatic triumph, with barely a cloud as far as the eye can see. But far from just contrasting with the Schnittke and the Shostakovich, it seemed to deepen their meaning and complete some complex whole — and brought the evening to a satisfying close.

Finally, may we offer quick praise to the unsung author of the evening’s program notes? These are generally a chore to read, padded with Historic Facts About the Composer, venues the performers have previously played and dullish thumb-twiddling on sonata form. But David Plylar, a music specialist at the Library, writes with refreshing thoughtfulness and insight — a real contribution to the concert experience.

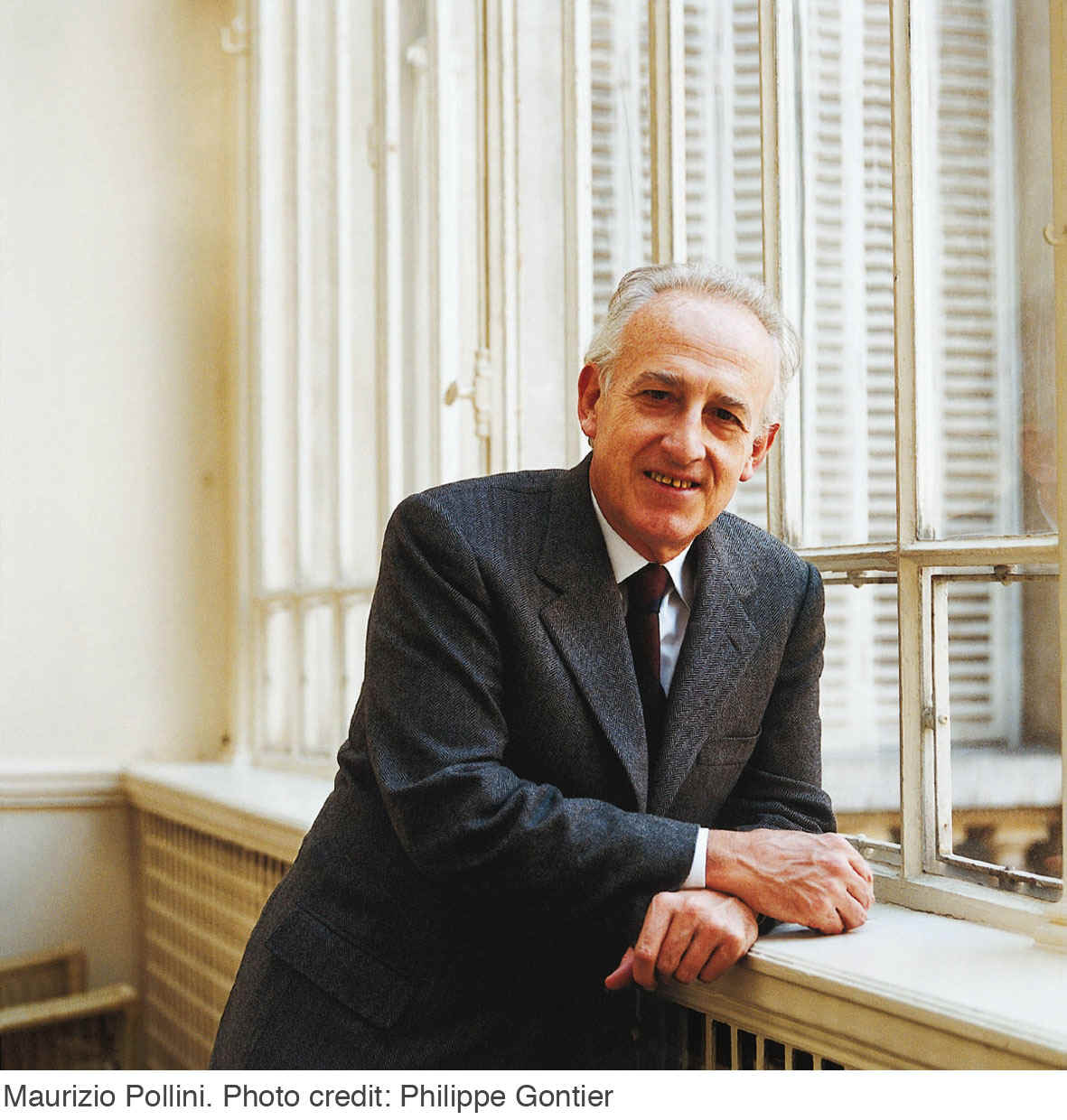

Maurizio Pollini at Strathmore

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • April 15, 2013

Love him or hate him, Maurizio Pollini has been one of the defining — and most polarizing — pianists of the last 50 years. His razor-sharp technique and modern, cooly intellectual approach to music have won legions of admirers, while his detractors hear austerity and a sort of bloodless, clinical detachment. But Pollini’s mastery of the keyboard is beyond reproach, and it was little wonder that the Music Center at Strathmore was packed Sunday afternoon for a program of Chopin and Debussy that — though it may not have converted agnostics — showed the 71-year-old Pollini is still provocative, still polarizing and still very much a force to be reckoned with. The first half of the afternoon was devoted to Chopin, a thoughtfully balanced mix that included the Prelude in C-sharp Minor, the second and third Ballades, the Four Mazurkas, Op. 33 and the Scherzo in C-sharp Minor, Op. 33. And, as expected, Pollini approached them with clear-eyed intelligence and an almost tangible sense of purpose, paring the music to its essentials with clarity and precise, microscopically calibrated detail.

The first half of the afternoon was devoted to Chopin, a thoughtfully balanced mix that included the Prelude in C-sharp Minor, the second and third Ballades, the Four Mazurkas, Op. 33 and the Scherzo in C-sharp Minor, Op. 33. And, as expected, Pollini approached them with clear-eyed intelligence and an almost tangible sense of purpose, paring the music to its essentials with clarity and precise, microscopically calibrated detail.

Some of the works responded to this treatment better than others (the concluding scherzo, in particular, was a fiery delight) and it was impossible not to be impressed. But it seemed equally difficult, in all frankness, to be genuinely moved. Despite the pearly tone and impeccable technique, there was little sense of spontaneity or warmth, no mystery and only the faintest impression of personal involvement. It felt as if Pollini were skillfully revealing each subtle layer of Chopin’s music — and then missing the beating heart at its core.

But any sense of disappointment was dramatically dispelled in the second half of the program. The first book of Debussy’s “Preludes” are among the most chimerical, delicately shaded works in the piano literature, and it was an open question whether they would wilt in Pollini’s steely grip. In fact, they blossomed. His phrasing, unforgiving in the Chopin, loosened and became far more supple and spontaneous, and he brought such vivid detail and imagination to the “Preludes” — from the subtle play of light and shadow in “Voiles” to the gentle lyricism of “La fille aux cheveux de lin” — that they seemed to burst uncannily into life. Even the most die-hard Pollini skeptic would have left impressed.

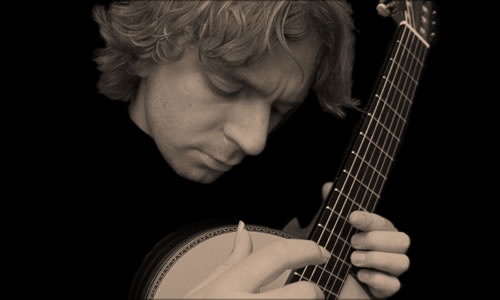

Marcin Dylla at The Marlow Guitar Series

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • April 14, 2013

Romanticism is alive and well, you may be glad to hear. At least, it was at Westmoreland Congregational United Church of Christ in Bethesda on Saturday night, when the Polish guitarist Marcin Dylla took the pulpit for an evening of unabashedly expressive music that ranged from Franz Schubert to the modern-day Magnus Lindberg. Dylla’s a world-class virtuoso — you don’t win first prize at 19 international competitions for nothing — and the evening was a riveting display of guitar technique. But it wasn’t his pinpoint accuracy that dazzled, so much as his deeply felt, almost sensual poeticism. This was playing of almost Romantic-era passion — and it was impossible not to be moved by it. Dylla opened the concert (the last of the season for the fine Marlow Guitar Series) with the “Sonata Romantica” by Mexican composer Manuel Maria Ponce. Written in 1928, it’s an overt homage to Schubert, full of songlike passages and quiet passions: Romanticism interpreted through cooler, 20th-century ears. Dylla (whose artful stubble and just-fell-out-of-bed hair gave him a suitably Romantic look) played it with extraordinary delicacy of touch, profound concentration and, you felt, almost starry-eyed affection.

Dylla opened the concert (the last of the season for the fine Marlow Guitar Series) with the “Sonata Romantica” by Mexican composer Manuel Maria Ponce. Written in 1928, it’s an overt homage to Schubert, full of songlike passages and quiet passions: Romanticism interpreted through cooler, 20th-century ears. Dylla (whose artful stubble and just-fell-out-of-bed hair gave him a suitably Romantic look) played it with extraordinary delicacy of touch, profound concentration and, you felt, almost starry-eyed affection.

But it was “Mano a Mano” — a thoroughly modern but, in its own way, equally Romantic work from the contemporary Finnish composer Lindberg — that proved the real heart of the evening. It’s a surging, wildly colored tour de force for the guitar, and Dylla unleashed it with a rare balance of control, passion and explosive power. If there were any doubt that music of the 21st century can be as personal and deeply expressive as that of the Romantics, it ended here.

The rest of the evening was milder by comparison: a pleasant sonata by Anton Diabelli that breezed in and out of the ears without much fuss, three songs by Schubert that were as lovely as you’d expect, and, to close the evening, the “Valses Poeticos” by Enrique Granados — a work of such captivating beauty that Dylla gracefully declined to play an encore when brought back by a standing ovation. “I want these beautiful melodies of Granados,” he told the audience, “to remain for a while in your ears.”

International Contemporary Ensemble at the Atlas Performing Arts Center

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • April 12, 2013

The world of contemporary classical music has not exactly been a barrel of laughs for the past half-century. Awash in academic theorizing and po-faced, who-cares-if-you-listen complexity, composers almost seemed to turn their backs on audiences — and audiences, not surprisingly, returned the favor. But that seems to be changing. A number of younger composers, rigorously trained but wary of the ivory tower’s isolation, are bringing a welcome sense of playfulness into music, embracing an anything-goes range of styles. Phyllis ChenThat, at any rate, was the impression Thursday night at the Atlas Performing Arts Center when the International Contemporary Ensemble showcased the music of Phyllis Chen and Carla Kihlstedt, two very different composer-performers whose music ran from delicate wisps of breath to foot-stomping bedlam.

Phyllis ChenThat, at any rate, was the impression Thursday night at the Atlas Performing Arts Center when the International Contemporary Ensemble showcased the music of Phyllis Chen and Carla Kihlstedt, two very different composer-performers whose music ran from delicate wisps of breath to foot-stomping bedlam.

Of the two, Chen is the more playful, the more quietly charming. A virtuoso of the toy piano, she delights in the delicate sonorities of music boxes and everyday objects, weaving them into strikingly original works of engaging lightness and transparency. Her soliloquy for the flute, for instance — “Beneath a Trace of Vapor,” played by Eric Lamb — is a complex sound scape built from breath, in which harmonics, overblown notes and a range of feathery sounds from the flute are deployed with precision and wild imagination. Likewise, “Hush” opened with a revolving-in-circles, Eric Satie-like simplicity but built in drive and power to become absolutely riveting.

Perhaps the most entertaining piece of the evening was “Mobius,” in which Chen randomly punched holes into a loop of paper as it was being cranked between a pair of music boxes. The paper “programmed” the music boxes to produce tones, the cranks generated mechanical ratcheting sounds, and the whole was processed through a MacBook nearby — until Chen brought the fun to a close by snipping the Mobius strip in half. Chen’s combination of playfulness, discipline and an unerring ear in mixing strange sonorities made it a captivating work. And her last piece of the evening, “Chimers” — which pits a clarinet and violin against a shimmering chorus of tuning forks — proved that Chen is a master of the art of play — serious, serious play. Carla KihlstedtKihlstedt took center stage for the second half of the evening, leading the ensemble through her new song cycle, “At Night We Walk in Circles and Are Consumed by Fire.” Commissioned by the ICE, it’s a theatrical, freewheeling work that leaps around the stylistic map, dipping fluently into everything from free jazz to Kurt Weil as it explores the mysteries of the unconscious mind. But it’s an easy, natural eclecticism; Kihlstedt is a seasoned musician with roots in both classical and pop, and “Night” was, to some degree, a showcase for her skills not just as a composer but as a performer as well.

Carla KihlstedtKihlstedt took center stage for the second half of the evening, leading the ensemble through her new song cycle, “At Night We Walk in Circles and Are Consumed by Fire.” Commissioned by the ICE, it’s a theatrical, freewheeling work that leaps around the stylistic map, dipping fluently into everything from free jazz to Kurt Weil as it explores the mysteries of the unconscious mind. But it’s an easy, natural eclecticism; Kihlstedt is a seasoned musician with roots in both classical and pop, and “Night” was, to some degree, a showcase for her skills not just as a composer but as a performer as well.

Simultaneously singing and playing the violin, often launching onto one foot to get the music airborne, Kihlstedt deployed her considerable stage presence. While her voice isn’t particularly big, it has a natural charm — flavored with a hint of Bjork — and she knows how to use it. Opening with the dreamy, improvised-feeling “Factual Boy,” she led the group through nine interwoven songs built on dreams that friends had told her about. That can be a risky approach — is anything more tedious than listening to other people’s dreams? — and there were moments of spoken text that slowed the momentum to a crawl.

But Kihlstedt has a rich musical imagination, and the music had a life of its own, moving with dreamlike clarity through tender fragments of song, stomping martial tunes, hymnlike reveries and the other strange, mysterious stuff that serves as a soundtrack to our unconscious.

Music of Hi Kyung Kim at the Freer Gallery

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • April 8, 2013

Composers have been smashing the boundaries between traditional Asian and contemporary Western music for years now, blending those apparently opposite worlds and producing a wealth of fascinating new music. The Korean-born composer Hi Kyung Kim is a master of the genre, and at the Freer Gallery on Sunday afternoon — joined by the Borromeo String Quartet and an unusual ensemble that uses both Korean and Western instruments — she showcased two new works that pushed both East and West into provocative new realms.

Hi Kyung KimThe premiere of Kim’s string quartet “Han San” opened the program. Inspired by an aerial photograph of a seaweed farm, it’s a richly colored work that leaps and tumbles along with irrepressible vitality, flavored with bent notes, frenetic tremolos and slithering glissandi, all to wonderfully expressive effect. A complex rhythmic structure — built, Kim noted, “around the breath rather than a beat” — underpinned the four-section work and gave it a sense of natural spontaneity, as if it were unfolding like some natural phenomenon. A masterful work, and the Borromeo players (reading their scores off MacBooks) navigated its complexities with easy virtuosity.

Hi Kyung KimThe premiere of Kim’s string quartet “Han San” opened the program. Inspired by an aerial photograph of a seaweed farm, it’s a richly colored work that leaps and tumbles along with irrepressible vitality, flavored with bent notes, frenetic tremolos and slithering glissandi, all to wonderfully expressive effect. A complex rhythmic structure — built, Kim noted, “around the breath rather than a beat” — underpinned the four-section work and gave it a sense of natural spontaneity, as if it were unfolding like some natural phenomenon. A masterful work, and the Borromeo players (reading their scores off MacBooks) navigated its complexities with easy virtuosity.

When the gifted composer Andrew Imbrie died in 2007, he left behind a detailed sketch for a clarinet quintet. Kim — a former student of Imbrie’s — decided to complete the work, and while it’s just a fragment of a single movement, it proved to have the sophisticated, approachable charm of much of Imbrie’s music. In the hands of clarinet superstar Richard Stoltzman (who joined the Borromeo for this performance), the work took on a kind of affectionate glow, full of songlike passages and delicately calibrated interplay between clarinet and strings.

But it was Kim’s “Thousand Gates” that really stole the show. Part of a planned multimedia epic, the 45-minute piece (whose title refers to the gates of heaven) mixed an anything-goes range of styles, instruments and cultural references into a joyful meditation on death and eternal life. Theatrical and often quite moving, it was also wildly uninhibited: A mournful soliloquy on a wooden Korean flute turned into a playful rendering of “You Are My Sunshine,” a Renaissance dance blossomed out of nowhere, a duet on a wood block became a titanic battle of sound. The whole thing built to an ecstatic climax that brought the audience to its feet. Spirited playing from the Ensemble Rituel (and the dancing percussionist Eun-Ha Park, in particular) made for a memorable afternoon.

The Great Noise Ensemble at the Atlas

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • April 7, 2013

The Great Noise Ensemble — as you’ve no doubt picked up from the name — is one of the more playful and uninhibited classical groups in town. Specializing in music from cutting-edge young composers, the group has been putting on concerts at the Atlas Performing Arts Center this year on themes such as “irreverence” and “revolution,” and on Friday night, the performance was titled — simply but with tantalizing promise — “Revelation.” Aleksandra VrebalovThere are plenty of ways to interpret that word, and the young Serbian composer Aleksandra Vrebalov — who was on hand for the event — approached it by magnifying tiny, “micro” musical structures and compressing “macro” ones to make them comprehensible and reveal their deeper connections. Her “Transparent Walls” opened with a simple, hypnotic pulse in the electric piano, then grew in color and complexity as the ensemble joined in, floating through a dreamlike landscape before gathering in power and erupting into a powerful, almost warlike explosion of sound (complete with wailing siren), and fading back again into simplicity.

Aleksandra VrebalovThere are plenty of ways to interpret that word, and the young Serbian composer Aleksandra Vrebalov — who was on hand for the event — approached it by magnifying tiny, “micro” musical structures and compressing “macro” ones to make them comprehensible and reveal their deeper connections. Her “Transparent Walls” opened with a simple, hypnotic pulse in the electric piano, then grew in color and complexity as the ensemble joined in, floating through a dreamlike landscape before gathering in power and erupting into a powerful, almost warlike explosion of sound (complete with wailing siren), and fading back again into simplicity.

The engaging Washington-born composer Daniel Felsenfeld was also there, and he described his three-movement piano concerto, “The Curse of Sophistication,” as being about reinventing himself as an artist — working through what he called his “weird combination of haughtiness and self-recrimination.” As an exercise in personal self-revelation, it was fascinating. A searching, edgy piano (played with great style by Molly Orlando Palmiero) sometimes battled, sometimes embraced a seductive and often lush orchestral background, as if trying to break through to some urgent and elemental musical core. The lavishly gifted composer Stephen Albert died some 20 years ago at the age of 51, and his “Treestone” — a song cycle built on James Joyce’s “Finnegans Wake”— underscores what a tragedy that was.

The lavishly gifted composer Stephen Albert died some 20 years ago at the age of 51, and his “Treestone” — a song cycle built on James Joyce’s “Finnegans Wake”— underscores what a tragedy that was.

Written for soprano, tenor and small ensemble, it’s a gorgeous work, as chimerical and wildly colorful as Joyce’s own poetic meta-language, full of wit and stunning atmospherics and a riverine sense of flow. It’s a dauntingly complex work, but music director Armando Bayolo led the ensemble — as he did all evening — with precision, imagination and tangible electricity.