Kaija Saariajo at the Phillips Collection

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • February 22, 2013

As a little girl, Kaija Saariaho often heard music as she was falling asleep — so she asked her mother if she could have a quieter pillow. The sounds, of course, were in her imagination, and in the intervening decades the Finnish composer went on to write music that seems to drift in gently from the unconscious, with the strange and otherworldly beauty of a dream. But it’s not just atmospherics; Saariaho herself was at the Phillips Collection on Thursday night for a performance of her music by members of the Canadian Opera Company Ensemble Studio, and it was clear by the end that there are few living composers with such subtle insight into the human psyche. The evening turned out to be largely about love. In “Lonh,” a work for soprano and electronics from 1996, Saariaho combined a medieval love poem (beautifully sung by Jacqueline Woodley in the ancient Occitan language) with an electronic score that manipulated bells and bird song to evoke a distant and almost luminous landscape. “Quatre Instants” for soprano and piano was more urgent and compelling — an “emotional journey,” as the composer put it, through the bliss and terrors of love, from the poignant “Longing” to the anguished cri de coeur of “Torment.”

The evening turned out to be largely about love. In “Lonh,” a work for soprano and electronics from 1996, Saariaho combined a medieval love poem (beautifully sung by Jacqueline Woodley in the ancient Occitan language) with an electronic score that manipulated bells and bird song to evoke a distant and almost luminous landscape. “Quatre Instants” for soprano and piano was more urgent and compelling — an “emotional journey,” as the composer put it, through the bliss and terrors of love, from the poignant “Longing” to the anguished cri de coeur of “Torment.”

The pianist Emanuel Ax commissioned Saariaho in 2005 to write a piece for him that would have, as she put it, “not a tune, exactly, but a strong sense of melody.” The result is the engaging “Ballade,” a sort of hyper-sophisticated Nordic blues full of sweeping gestures and moody near-melodies, which received a rich, flavorful reading from pianist Elizabeth Upchurch. But the most gripping music of the evening may have been the duet from “Grammaire des Reves” — based on texts by Sylvia Plath — that explored the sometimes-warring, sometimes-integrated sides of the unconscious. Soprano Mireille Asselin and the mezzo-soprano Rihab Chaieb turned in a spectacular performance as two halves of the same whole, balancing tension and synergy as they clutched at each other and drifted apart throughout the work.

João Paulo Figueirôa at Westmoreland Church

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • February 18, 2013

Where would contemporary guitar music be without Brazil? Over the past hundred years, composers from Heitor Villa-Lobos to Sergio Assad have pushed the guitar into colorful, wildly imaginative new sound-worlds, and on Saturday night the Brazilian guitarist João Paulo Figueirôa explored some of that intriguing repertoire at Westmoreland Congregational Church, as part of the always-interesting Marlow Guitar Series. The evening got off to a shallow start — an instantly forgettable bit of fluff by the 19th-century guitarist J. Kaspar Mertz — but quickly entered deeper waters. Bach’s spare-but-majestic Lute Suite in G Minor, BWV 995, is one of the great works of the repertoire, and Figueirôa approached it with respect — perhaps even to a fault. He seemed most at home in the slow movements and found much subtle beauty there, but overall it was a rather polite, distant performance, never generating the power that builds throughout the work and gives it its profound, unstoppable momentum. Figueirôa seemed to be a gentle poet of the guitar — quietly introspective, musically soft-spoken, and not out to ruffle any ears.

The evening got off to a shallow start — an instantly forgettable bit of fluff by the 19th-century guitarist J. Kaspar Mertz — but quickly entered deeper waters. Bach’s spare-but-majestic Lute Suite in G Minor, BWV 995, is one of the great works of the repertoire, and Figueirôa approached it with respect — perhaps even to a fault. He seemed most at home in the slow movements and found much subtle beauty there, but overall it was a rather polite, distant performance, never generating the power that builds throughout the work and gives it its profound, unstoppable momentum. Figueirôa seemed to be a gentle poet of the guitar — quietly introspective, musically soft-spoken, and not out to ruffle any ears.

But in the second half of the program — which was dedicated to the music of Brazilian composers — he began to come alive. Two works by Egberto Gismonti (the wistful ballad “Água e Vinho” and the mile-a-minute “Loro”) let Figueirôa visibly relax, and he tossed off Gismonti’s jazz-inflected melodies with obvious pleasure. Villa-Lobos’s “Mazurka-Choro” got a sharp-edged reading, and things turned even more interesting in the dark, unsettling “Etude No. 12.” Figueirôa dug into it with a kind of tough-minded intensity he hadn’t shown in the earlier works, as if he’d suddenly caught on fire.

It was Assad’s “Aquarelle,” though, that really stole the show. It’s a tour-de-force for guitar with an improvisational, almost whimsical feel, full of quicksilver twists and turns and delicate shades of color. Figueirôa gave it a lively and imaginative reading, and it was clear he was in his element. As an ambassador of Brazilian music, this is a guitarist worth hearing.

Marouan Benabdallah at the Phillips Collection

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • February 11, 2013

It’s probably a good idea to get out of Marouan Benabdallah’s way when he sits down to play Bartok. The young Moroccan pianist has a powerful, even ferocious technique, and — as he proved at the Phillips Collection on Sunday afternoon — takes an almost palpable joy in the driving rhythms and biting, aggressive harmonies of Bartok’s music. The whole first half of the program, in fact, was devoted to the Hungarian composer, from five of the edgy-but-beguiling “Mikrokosmos” etudes (played with incisiveness and color to spare) and the early Elegy, Op.8b, No. 2 (lush to an almost Lisztian degree), to the jaunty, anything-goes Scherzo from the youthful “Four Piano Pieces” — all brought off with a kind of exuberant wildness and virtually perfect control. Benabdallah’s mother is Hungarian, which perhaps accounts for some of his his natural way with Bartok. But he proved equally adept at the far different music of Debussy, retracting his claws to bring a lighter (if distinctly dry-eyed) touch to three of the “Images” from 1907. These works — particularly the shimmering “Poissons d’or” — are often played for their impressionistic, atmospheric effects, but Benabdallah managed to bring out their delicate poetry while keeping everything in sharp focus.

Benabdallah’s mother is Hungarian, which perhaps accounts for some of his his natural way with Bartok. But he proved equally adept at the far different music of Debussy, retracting his claws to bring a lighter (if distinctly dry-eyed) touch to three of the “Images” from 1907. These works — particularly the shimmering “Poissons d’or” — are often played for their impressionistic, atmospheric effects, but Benabdallah managed to bring out their delicate poetry while keeping everything in sharp focus.

Two short sonatas rounded out the afternoon: the robust and engagingly lyrical “Sonata Breve” by the contemporary Argentinian composer Maximo Flugelman and Scriabin’s two-movement Sonata in F-sharp Major, Op.30, No.4, from 1903. Depending on the bent of your ears, Scriabin was either a mystical genius or a tedious blowhard (the jury may be forever out), but Benabdallah’s incisive, finely drawn approach made the work bearable even to skeptics.

Part of what made the afternoon so enjoyable, it should briefly be noted, was a new configuration of the Phillips’s venerable Music Room. It has never been an ideal place for chamber music, with the “stage” area divided from the audience by columns that form a sort of psychological barrier. But Benabdallah played in the main part of the room, with the audience in a semicircle around him, creating a more intimate, relaxed and pleasantly communal experience. Audience reaction seemed very positive; this vote, for one, goes for making the new setup permanent.

Harlem Quartet & Misha Dichter at the Terrace Theater

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • February 7, 2013

When you think of string quartet composers, Chick Corea probably isn’t the first name that pops into mind. But the pathbreaking jazz pianist — better known for his fusion music of the 1970s, when he headed the supergroup Return to Forever — has been venturing onto traditionally classical turf in recent years, and his jazzy, sophisticated “Adventures of Hippocrates” was the centerpiece of the Harlem String Quartet’s imaginative concert Wednesday night at the Terrace Theater, part of the Kennedy Center’s Fortas Chamber Music series. The young Harlem players were joined by the pianist Misha Dichter for most of the program, and it proved a good match: Balanced, robust, flavorful playing was the hallmark of the evening. Shostakovich’s Piano Quintet in G Minor, Op. 57, opened the concert, and though it took the ensemble a few minutes to settle in (the Bach-inspired prelude and fugue that opens the work seemed a bit ungainly, and a little more bite would have sharpened the scherzo’s sardonic edge), it turned into a fine, full-blooded performance by the end.

The young Harlem players were joined by the pianist Misha Dichter for most of the program, and it proved a good match: Balanced, robust, flavorful playing was the hallmark of the evening. Shostakovich’s Piano Quintet in G Minor, Op. 57, opened the concert, and though it took the ensemble a few minutes to settle in (the Bach-inspired prelude and fugue that opens the work seemed a bit ungainly, and a little more bite would have sharpened the scherzo’s sardonic edge), it turned into a fine, full-blooded performance by the end.

Corea’s “Adventures of Hippocrates” (the title comes from one of L. Ron Hubbard’s science-fiction novels) moved things in a lighter direction. It’s a five-movement suite full of Corea’s darting, restless rhythms, dancing from a tango to a waltz to a ballad to a fast-moving finale, and the Harlem players brought it off with spirit and almost casual virtuosity. No wonder Corea invited the group to tour with him last year.

But it may have been Schumann’s passionate, lushly melodic Piano Quintet in E-flat, Op. 44, that stole the show. This is a work that’s often polished to a high gloss, but Dichter and the Harlem players adopted a down-to-earth, whole-grain approach, sacrificing delicacy for strength and resonance — a bravura performance that won them a standing ovation.

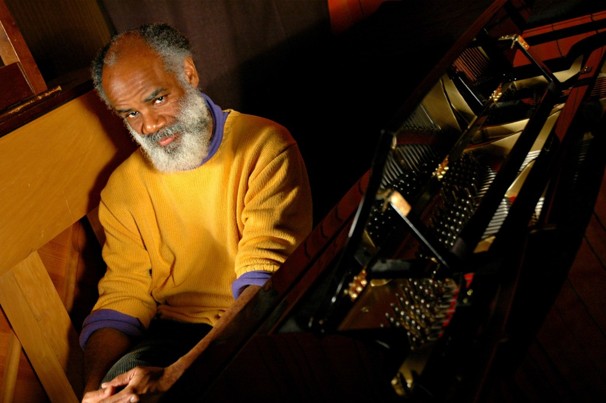

Jeffrey Mumford at the National Gallery of Art

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • February 4, 2013

Jeffrey Mumford is the composer-in-residence at the National Gallery of Art this year, and it’s a fitting distinction, given that Mumford is a native of the District and has long been a central figure in the small-but-feisty contemporary music scene here. The gallery is mounting three concerts this month to celebrate Mumford’s music, and the first — performed in the East Building on Sunday night by the museum’s New Music Ensemble — offered an illuminating glimpse into the composer’s complex and richly imaginative music, in which an almost romantic sensibility seems to radiate through a thoroughly contemporary surface. The first two pieces on the program (which was titled “Multiple Voices” — a nod both to Mumford’s multilayered style and to other composers who influenced or were influenced by him) underscored that combination. Brahms’s Intermezzo No. 2 in A is a profoundly emotional work, which Mumford says has drawn him to it from a young age, and it was given a warm, nuanced reading by pianist Lura Johnson. It was immediately contrasted with Elliott Carter’s “String Trio” from 2011, a short but challenging work to which violist Jonathan Richards — in the lead role — brought real drama.

The first two pieces on the program (which was titled “Multiple Voices” — a nod both to Mumford’s multilayered style and to other composers who influenced or were influenced by him) underscored that combination. Brahms’s Intermezzo No. 2 in A is a profoundly emotional work, which Mumford says has drawn him to it from a young age, and it was given a warm, nuanced reading by pianist Lura Johnson. It was immediately contrasted with Elliott Carter’s “String Trio” from 2011, a short but challenging work to which violist Jonathan Richards — in the lead role — brought real drama.

Carter was a teacher of Mumford’s, and his influence was abundantly clear in the works that followed. Mumford’s engaging “Tango-Variations” was performed in two versions, the 1984 original (for solo piano) and a more recent revision for chamber orchestra, which opened up the work and revealed its shifting planes of sound. A string trio from 2008 titled “in soft echoes . . . a world awaits” followed, and its 15 miniature movements — some only a few seconds long — were built on Mumford’s long-standing fascination with light — in this case, the light within clouds.

A feisty little piano etude by the composer Courtney Bryan, a former pupil of Mumford’s, followed, but the most stunning work of the evening was Mumford’s own deeply personal work for solo violin titled “an expanding distance of multiple voices,” played by violinist Lina Bahn. It’s a remarkable work, and Bahn (for whom it was written) played it with insight and obvious commitment. More of Mumford’s music will be presented at 6:30 p.m. Feb. 10 and 17 at the National Gallery. For anyone interested in new music, it’s well worth hearing.

Laurie Anderson premieres "Landfall" at the Clarice Smith Center

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • February 4, 2013

Laurie Anderson — musician, storyteller, venerable pixie of the New York downtown art scene — has long been in love with language.

She doesn’t just tell stories; she draws out every word with a kind of physical pleasure, tasting its flavor as she probes the everyday mysteries of life. Those mysteries — and the nature of language itself — were at the heart of Anderson’s “Landfall: Scenes from My New Novel,” a riveting, gorgeous new multimedia work that she premiered this weekend at the University of Maryland’s Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center, in collaboration with the equally venerable (if not as pixie-ish) Kronos Quartet. “Don’t you hate it when people tell you their dreams?” asked Anderson early in the work, and she was off, telling us her dreams in an unstoppable flood. There were meditations on sonic illusions, on our unrequited yearning for the stars, on the silence of the letter “aleph,” on the tireless extinction of species — all deftly interwoven over a hypnotic drone of repeated gestures from the quartet. Dreamlike, to be sure, and almost ritualistic as well, with spotlights playing through smoke across the dark stage and strings of glyphs scrolling impassively across a gigantic screen.

“Don’t you hate it when people tell you their dreams?” asked Anderson early in the work, and she was off, telling us her dreams in an unstoppable flood. There were meditations on sonic illusions, on our unrequited yearning for the stars, on the silence of the letter “aleph,” on the tireless extinction of species — all deftly interwoven over a hypnotic drone of repeated gestures from the quartet. Dreamlike, to be sure, and almost ritualistic as well, with spotlights playing through smoke across the dark stage and strings of glyphs scrolling impassively across a gigantic screen.

But a kind of quiet, poignant and very human quality ran through “Landfall” as well. Anderson — a mischievous presence in her electro-shocked hair and red elf boots — plumbs her own life for sly, sideways observations, then weaves them into almost cosmic-scaled ruminations laced with a sense of humor that sets her apart from the more po-faced avant-garde.

“I was in a Dutch karaoke bar, trying to sing a song in Korean,” she offered, and soon was pushing out the edges of language itself, tying together her own vocoder-distorted voice, the quartet’s playing (connected to the text via software) and the strange, urgent hybrid of letters and symbols that flashed on the screen behind her in a still-unknown meta-language of the future.

The effect was stunning — and proof, if any were needed, that Anderson continues to be one of the most engaging and forward-looking artists around.

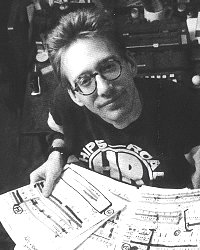

Brooklyn Rider at the Sixth & I Historic Synagogue

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • January 27, 2013

A wildly eclectic audience packed the Sixth & I Historic Synagogue on Saturday night, as the classical-music cognoscenti sat cheek-by-aging-jowl with high school students and hipsters of every stripe. But that’s what you expect in a concert by Brooklyn Rider, an adventurous young string quartet devoted to keeping the traditional quartet repertoire alive while dragging the form — kicking and screaming, if necessary — into the anything-goes postmodern world of the 21st Century.  What makes the Riders particularly interesting is how they draw out the almost neural connections between composers and artists of different eras. Mendelssohn’s String Quartet No. 1 in E-flat, Op. 12 (an unabashedly Romantic work), opened the evening, and the Riders gave it an extremely warm, glowing reading — maybe a bit smudgy in the details and lacking in bite, but deeply involving nonetheless. Their real point, however, was to underscore the ties between Mendelssohn and Beethoven — and then between Beethoven and such modern composers as John Zorn, whose quietly searing “Kol Nidre” and a stunning quartet from 2011 drew overtly from Beethoven’s quartets.

What makes the Riders particularly interesting is how they draw out the almost neural connections between composers and artists of different eras. Mendelssohn’s String Quartet No. 1 in E-flat, Op. 12 (an unabashedly Romantic work), opened the evening, and the Riders gave it an extremely warm, glowing reading — maybe a bit smudgy in the details and lacking in bite, but deeply involving nonetheless. Their real point, however, was to underscore the ties between Mendelssohn and Beethoven — and then between Beethoven and such modern composers as John Zorn, whose quietly searing “Kol Nidre” and a stunning quartet from 2011 drew overtly from Beethoven’s quartets. John ZornThat kind of interconnectivity was the hallmark of the evening. Composer Christina Courtin drew on Stravinsky’s neoclassical period for her charming, dancelike “tralala,” and Dana Lyn was inspired by the visual artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles for her “Maintenance Music,” which used sliding microtones and jagged, repeated motifs to atmospheric (if slightly queasy) effect. The snapping fingers, stomping feet and final leap into the air of Vijay Iyer’s jazzy “Dig the Say” echoed the great James Brown, and Colin Jacobsen’s “Three Miniatures for String Quartet” created lush, Persian-flavored sound-gardens of extraordinary beauty.

John ZornThat kind of interconnectivity was the hallmark of the evening. Composer Christina Courtin drew on Stravinsky’s neoclassical period for her charming, dancelike “tralala,” and Dana Lyn was inspired by the visual artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles for her “Maintenance Music,” which used sliding microtones and jagged, repeated motifs to atmospheric (if slightly queasy) effect. The snapping fingers, stomping feet and final leap into the air of Vijay Iyer’s jazzy “Dig the Say” echoed the great James Brown, and Colin Jacobsen’s “Three Miniatures for String Quartet” created lush, Persian-flavored sound-gardens of extraordinary beauty.

But it was the two works by Zorn that — to these ears, anyway — really made the night. Zorn is one of the most imaginative and prodigiously gifted composers of this or any other era, and his quartet “The Alchemist” is, simply put, a masterpiece — an absolute tour de force. Explosively inventive, deeply human, utterly fascinating from first note to last, the work is built around the theme of Beethoven’s famous Grosse Fuge, Op. 133, but takes it into freewheeling new realms.

The Riders — clearly committed to the work — gave it a breathtaking performance.