miXt Trio at the Terrace Theater

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • December 5, 2012

Technical perfection is almost a given among young classical musicians these days; even the most newly minted graduates can toss off virtuosic works with ease. But it’s not as easy to find players who embody the sheer joy of making music, which made Tuesday’s debut performance by miXt — a trio of award-winning soloists from the Young Concert Artists organization — such a remarkable evening. In their freewheeling program at the Kennedy Center’s Terrace Theater, the players caromed happily from klezmer to Schubert to ragtime to 20th-century modernism, bringing sophistication, imagination and down-to-earth exuberance to everything they played. Much of that was due to the extroverted Spanish clarinetist Jose Franch-Ballester, whose wit and virtuosity were quickly apparent in Bela Bartok’s “Contrasts.” It’s a work from 1938 that bristles with prewar edginess and bite, but Franch-Ballester brought an agreeable warmth to the work, giving the slow “Piheno” movement a kind of serene luminosity, and deepening the sly, ironic jauntiness in the closing “Sebes.”

Much of that was due to the extroverted Spanish clarinetist Jose Franch-Ballester, whose wit and virtuosity were quickly apparent in Bela Bartok’s “Contrasts.” It’s a work from 1938 that bristles with prewar edginess and bite, but Franch-Ballester brought an agreeable warmth to the work, giving the slow “Piheno” movement a kind of serene luminosity, and deepening the sly, ironic jauntiness in the closing “Sebes.”

The lyrical “Three Nocturnes” by Kevin Puts (a former YCA composer-in-residence) that followed received an even more impressive performance, from the quietly exalting clarinet lines of the Con Moto section to the otherworldly grandeur of the Molto Adagio, played with great subtlety and insight by pianist Ran Dank.

Violinist Bella Hristova put her ferocious virtuosity on display in Schubert’s spirited Rondo in B Minor, D. 895, but the real excitement came in the closing works. As Dank churned out the strutting ragtime rhythms of John Novacek’s “Four Rags for Two Jons,” Franch-Ballester unleashed soaring, exuberant lines on the clarinet, tossing in foot-stomping, finger-snapping and the occasional shout as needed. He’s a born showman with a big, rich sound, and Paul Schoenfield’s “Trio” — inspired by Hasidic music — let the three cut loose with a wild, uninhibited performance that brought the audience to its feet.

Hermitage Piano Trio at the Phillips Collection

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • December 3, 2012

They were squeezing chairs into every last inch of the Music Room at the Phillips Collection on Sunday, and little wonder: Three of Russia’s most spectacular young soloists had teamed up for an afternoon of mostly-Russian music, and it promised to be an extraordinary afternoon, steeped in the kind of magnificent tragedy that Russians do best. In fact, it was: From the first hushed notes of Rachmaninoff’s “Trio élégiaque,” No. 1, to the almost ecstatic despair of Tchaikovsky’s Trio in A Minor, Op. 50, the Hermitage Piano Trio turned in a performance of such power and sweeping passion it left you nearly out of breath. Rachmaninoff wrote his “Trio élégiaque” in 1892 when he was only 19, but there’s little in this work that feels callow or thin. The Hermitage players — Misha Keylin on violin, cellist Sergey Antonov, and Maxim Mogilevsky at the piano — opened the work with great tenderness, building it with utter naturalness into a searing outpouring of grief. The piano takes a leading role and Mogilevsky shone appropriately, and it’s almost impossible to say too many good things about violinist Keylin (whose phrasing and tone are impeccable) and, in particular, Antonov (who to these ears seems destined for cello superstardom). But more striking even than the individual virtuosity was the profound level of integration among the players, who showed a rare degree of ensemble from beginning to end.

Rachmaninoff wrote his “Trio élégiaque” in 1892 when he was only 19, but there’s little in this work that feels callow or thin. The Hermitage players — Misha Keylin on violin, cellist Sergey Antonov, and Maxim Mogilevsky at the piano — opened the work with great tenderness, building it with utter naturalness into a searing outpouring of grief. The piano takes a leading role and Mogilevsky shone appropriately, and it’s almost impossible to say too many good things about violinist Keylin (whose phrasing and tone are impeccable) and, in particular, Antonov (who to these ears seems destined for cello superstardom). But more striking even than the individual virtuosity was the profound level of integration among the players, who showed a rare degree of ensemble from beginning to end.

The Rachmaninoff and the Tchaikovsky are a natural pair, linked both in structure and elegaic tone, and bookended the performance. Beethoven’s Variations in G for Piano Trio, Op. 121a (known as the “Kakadu Variations”) provided a lightweight buffer between the two, and the Hermitage turned in an agreeable reading. But it was clear they were reserving their real powers for the Tchaikovsky, a work huge in both size — it’s a good 40 minutes long — and emotion. And it received a huge performance as well, brilliantly calibrated and perfectly understood, with a a final “Allegro risoluto e con fuoco” that swept like a tornado through the room — a bravura performance that brought the audience to its feet.

Anna Han at the Phillips Collection

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • November 26, 2012

One of the perks of winning the New York International Piano Competition is a recital at the Phillips Collection, and on Sunday afternoon, the prodigiously gifted Anna Han — who walked off with this year’s prize at the tender age of 16— put on a display of imagination, taste and pianistic firepower that was far beyond her years. It may have been Han’s naturalism and grace at the piano, though, that impressed the most. In a little-of-everything program that ranged from baroque to contemporary, she showed herself equally at home with Haydn (whose lively Sonata in E, Hob. XVI:31 came off with precision and playful charm), Rachmaninoff (a diaphanous, delicate “Lilacs,” Op. 21, No. 5) and the brilliant young Israeli composer Avner Dorman, whose colorful and accomplished Three Etudes were written for the New York competition. Technically daunting and stylistically complex, the Dorman studies came alive in Han’s hands, from the intricate, twisting lines of “Snakes and Ladders,” to the dark anger of “Funeral March” and the shimmering luminosity of the Ravel-like “Sundrops Over Windy Water.”

It may have been Han’s naturalism and grace at the piano, though, that impressed the most. In a little-of-everything program that ranged from baroque to contemporary, she showed herself equally at home with Haydn (whose lively Sonata in E, Hob. XVI:31 came off with precision and playful charm), Rachmaninoff (a diaphanous, delicate “Lilacs,” Op. 21, No. 5) and the brilliant young Israeli composer Avner Dorman, whose colorful and accomplished Three Etudes were written for the New York competition. Technically daunting and stylistically complex, the Dorman studies came alive in Han’s hands, from the intricate, twisting lines of “Snakes and Ladders,” to the dark anger of “Funeral March” and the shimmering luminosity of the Ravel-like “Sundrops Over Windy Water.”

Han fully hit her stride in an assured and absolutely engrossing account of Chopin’s “Nocturne” in C Minor, Op. 48, No. 1, building its complex tensions to a searing climax. And any doubts about the depth and musicality of Han’s playing were swept away in a bravura performance of Sergei Prokofiev’s Sonata in A Minor, Op. 28, No. 3. Played with such incisive power and assurance that you felt you could follow her into battle, Han showed herself completely worthy of the prizes she’s been racking up — a pianist barely at the beginning of her career, but already with a great deal to say.

Apollon Musagète at the Library of Congress

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • November 18, 2012

It’s hard not to like the Apollon Musagète String Quartet. They're young, they’re hip, they have that ultra-cool name and they play with people like Tori Amos. So when this newly minted (and already much-admired) Polish ensemble appeared at the Library of Congress on Friday, it looked like the evening was going to be a blast. And, it was — though maybe not always in the best sense. From the first brash, bright notes of Haydn’s Quartet in C Major, Op. 76, No. 3, the Apollons made it clear they were there to power their way through the evening. Haydn can take that kind of treatment; there’s nothing fragile about his music, and the quartet’s punchy, turn-up-the-amps approach packed a lot of weight into the work. But much of what you look for in Haydn’s quartets — the subtle humor, the crisp interplay among the instruments, the perfectly calibrated dance of ideas — was often lost in the scrum, and you couldn’t help but feel a little battered by the end.

And, it was — though maybe not always in the best sense. From the first brash, bright notes of Haydn’s Quartet in C Major, Op. 76, No. 3, the Apollons made it clear they were there to power their way through the evening. Haydn can take that kind of treatment; there’s nothing fragile about his music, and the quartet’s punchy, turn-up-the-amps approach packed a lot of weight into the work. But much of what you look for in Haydn’s quartets — the subtle humor, the crisp interplay among the instruments, the perfectly calibrated dance of ideas — was often lost in the scrum, and you couldn’t help but feel a little battered by the end.

That was the tone throughout the evening: enthusiastic playing undermined by roughness, a tendency toward obvious phrasing and a kind of every-man-for-himself sense of ensemble. Exhilarating at times, it could also be maddening. The dark, complex lyricism of the Quartet No. 1 in C Major, Op. 37 by the Polish composer Karol Szymanowski, for instance, is rooted in the composer’s harrowing experiences during World War I, but it never really felt convincing — its tenderness milked for effect, its luminous pathos lost to forceful declamation.

But there was much in the evening to admire, as well. The “Meditation on the Old Czech Chorale ‘Saint Wenceslas,’ ” Op. 35a, by Czech composer Josef Suk came off beautifully, and Felix Mendelssohn’s Quartet No. 2 in A Minor, Op. 13, was full of life and color. The Apollon may not be the most subtle quartet on the planet, but it plays with real vitality and excitement, which not every group can match. A few more years of seasoning, and it could be spectacular.

Dido and Aeneas, El Amor Brujo at Source Theater

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • November 18, 2012

There’s a lot to be said for downsizing opera. Pare away the usual excesses — the cavernous halls, the lavish sets, the high-priced superstars and the general over-the-topness — and you can take more risks, showcase emerging performers and present music on a more intimate, up-close-and-personal scale. And the approach works, to judge by Saturday night’s sold-out performance of “Pocket Opera x 2: Love and Witchcraft,” two entertaining “mini-operas” presented by the In Series at the tiny Source theater on 14th Street NW. The two works couldn’t be more different. Henry Purcell’s “Dido and Aeneas” is a charming baroque masterpiece with an almost comically tragic end, while Manuel de Falla’s “El Amor Brujo” (“Love by Sorcery”) is not even an opera at all, but a searing dance suite written in a 20th-century Andalusian gypsy style.

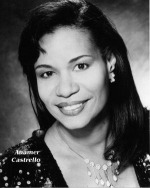

And the approach works, to judge by Saturday night’s sold-out performance of “Pocket Opera x 2: Love and Witchcraft,” two entertaining “mini-operas” presented by the In Series at the tiny Source theater on 14th Street NW. The two works couldn’t be more different. Henry Purcell’s “Dido and Aeneas” is a charming baroque masterpiece with an almost comically tragic end, while Manuel de Falla’s “El Amor Brujo” (“Love by Sorcery”) is not even an opera at all, but a searing dance suite written in a 20th-century Andalusian gypsy style. But it was an inspired combination. Mezzo-soprano Anamer Castrello took the lead in both works, bringing a dark, moving passion to the role of Dido, the queen of Carthage, who is torn from her lover Aeneas (a solid Robert Yacoviello) by witches and the will of the gods. Despite a dauntingly minimal set — a chaise longue, a few sticks and a galvanized steel bucket — a fine young cast largely made up of local singers and dancers brought the “Dido and Aeneas” alive with charm and lighthearted wit. A string quartet under the direction of harpsichordist Paul Leavitt delivered a spirited reading of the score, Adrienne Starr made a deliciously evil and feline Sorceress, and soprano Tia Wortham’s hysterical turn as Mercury was worth the price of admission on its own.

But it was an inspired combination. Mezzo-soprano Anamer Castrello took the lead in both works, bringing a dark, moving passion to the role of Dido, the queen of Carthage, who is torn from her lover Aeneas (a solid Robert Yacoviello) by witches and the will of the gods. Despite a dauntingly minimal set — a chaise longue, a few sticks and a galvanized steel bucket — a fine young cast largely made up of local singers and dancers brought the “Dido and Aeneas” alive with charm and lighthearted wit. A string quartet under the direction of harpsichordist Paul Leavitt delivered a spirited reading of the score, Adrienne Starr made a deliciously evil and feline Sorceress, and soprano Tia Wortham’s hysterical turn as Mercury was worth the price of admission on its own.

It was Castrello’s evening, though, as she proved in the Falla piece. With music director Carlos Rodriguez at the piano, she sang the role of Candelas — a woman trying to rid herself of the ghost of her dead lover — with elemental, smoldering heat, as dancers Heidi Kershaw and Kyle Lang swirled around the blood-red set in a passionate pas de deux. A fine and often moving evening all around, “Love and Witchcraft” continues through Nov. 26.

Ariel Quartet and Orion Weiss at the Terrace Theater

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • November 12, 2012

Cataclysmic times, it’s often said, produce great art. Take the early 20th century, when a Europe ripped apart by war and social upheaval suddenly found 19th century Romanticism irrelevant — and began giving birth to the revolutionary, exhilarating and world-changing movement known as Modernism.

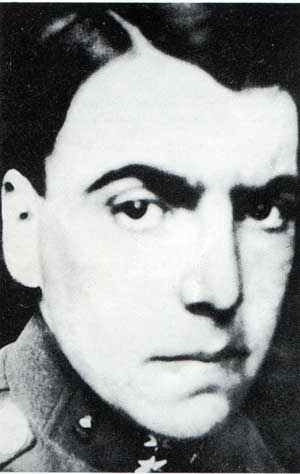

That transition was the focus of an intriguing concert titled “Between Two Worlds: Jewish Voices in Modern European Music” on Sunday night at the Terrace Theater, where the Ariel String Quartet teamed up with pianist Orion Weiss for the music of composers from Arnold Schoenberg to the brilliant but little-known Erwin Schulhoff — all profoundly shaped by the trauma of their times. Erwin SchulhoffOne of the most unusual figures of the period, Schulhoff was a wildly inventive Czech composer (one movement of his 1919 “Five Picturesques” is entirely silent, predating John Cage by decades) who died in a concentration camp in 1942. His String Quartet No. 1, written in 1924, is a virtual snapshot of the era: taut, explosive modernist gestures burst through the music as if impatient to be born. A fascinating work — and necessary listening for anyone interested in the period — it was brought off with style and wit by the young Ariel players.

Erwin SchulhoffOne of the most unusual figures of the period, Schulhoff was a wildly inventive Czech composer (one movement of his 1919 “Five Picturesques” is entirely silent, predating John Cage by decades) who died in a concentration camp in 1942. His String Quartet No. 1, written in 1924, is a virtual snapshot of the era: taut, explosive modernist gestures burst through the music as if impatient to be born. A fascinating work — and necessary listening for anyone interested in the period — it was brought off with style and wit by the young Ariel players.

Orion Weiss, last heard at the Terrace in a brilliant recital back in January, took the stage for the second of Schoenberg’s Three Piano Pieces, Op. 11 from 1909. Weiss has both powerful technique and exceptional insight, and brought an almost sculptural presence and weight to the music. Erich Korngold’s melodic String Quartet No. 3 in D Major, Op. 34 followed, bringing an elegant if not exactly revolutionary close to the first half of the evening. Written in 1945, as the composer abandoned a successful career in Hollywood, it recasts some of his best-known melodies — including the theme from the film “Between Two Worlds” — in a more “serious” classical vein.

But the indisputable climax of the program (which marked the opening of Pro Musica Hebraica’s sixth season) was Ernest Bloch’s magnificent 1923 Quintet for Piano and Strings No. 1. It’s an absolute juggernaut of a work, a pull-out-the-stops gallop into the modern world, full of huge and hungry gestures and ferocious intensity. With Weiss at the piano, the Ariel players seemed to come completely into their own for the first time all evening, playing with exceptional boldness and confidence — a blazing, larger-than-life performance that seemed to celebrate the triumph of the human spirit, even from the depths of chaos.

Morton Subotnick at the Library of Congress

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • November 11, 2012

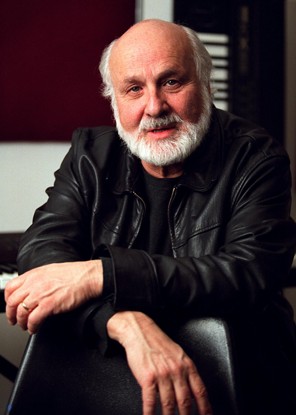

Since his path-breaking “Silver Apples of the Moon” brought electronic music into the mainstream in 1967, the composer Morton Subotnick, who turns 80 in April, has grown from a pioneer of electronic music to one of its elder statesmen. But he’s still very much on the ramparts, and on Friday night Subotnick — joined by the new-music vocalist Joan La Barbara and two other stalwarts of New York’s new-music scene — took the stage at the Library of Congress for three of Subotnick’s works that probed the complex intersections between music, technology, visual arts and the composer’s remarkable imagination. The evening opened with the seductive quiet of “Many” and “Rocking” from Subotnick’s 2007 work, “The Other Piano.” As Kathleen Supové played a repetitive, almost murmuring figure at the piano, the composer — manning an array of computers at the edge of the stage — processed the sound and added layer upon layer of complexity and depth and sheer volume to it. The result was gorgeous: a shimmering, hypnotic field of sound that swept over and around the audience, building slowly and with great subtlety into an almost physical embrace.

The evening opened with the seductive quiet of “Many” and “Rocking” from Subotnick’s 2007 work, “The Other Piano.” As Kathleen Supové played a repetitive, almost murmuring figure at the piano, the composer — manning an array of computers at the edge of the stage — processed the sound and added layer upon layer of complexity and depth and sheer volume to it. The result was gorgeous: a shimmering, hypnotic field of sound that swept over and around the audience, building slowly and with great subtlety into an almost physical embrace.

The tone changed when the redoubtable violinist Todd Reynolds joined them for “Trembling,” a far more aggressive, even brutal work from 1983. It’s a powerful piece, but rough pizzicati and harsh scraping on the amplified violin, made even rougher and harsher via Subotnick’s electronic processing, raised the edginess to ear-bleed levels.

The focus of the evening, though, was on the world premiere of “Lucy: Song and Dance” for female voice, live electronics and live video animation. Subotnick describes it as “an opera without words,” but it’s more of an opera before words, built from the sounds primitive humans might have made before coherent language emerged.

It’s an intriguing idea, and the always impressive La Barbara summoned a range of gentle cries, whispers, elemental squeaks and whatnot — what Subotnick blandly describes as “pitch-gestures” — while waves of video by the German artist Lillevan washed over her. It was often quite beautiful but in the end felt oddly tame and eager to please. We didn’t evolve into little bunnies, after all — there was more elemental screaming than mewing “pitch-gestures” in the evolution of human thought, and the soothing prettiness of “Lucy” left this listener, at least, grunting in disappointment.