Momenta Quartet at the Freer Gallery

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • November 9, 2012

Title a concert of new music “Inspired by Buddhism,” and John Cage — the pathbreaking composer influenced in the 1950s by Zen philosopher Daisetz Suzuki — leaps quickly to mind. But Buddhist thought is shaping a fresh new generation of composers, as well, as the young Momenta String Quartet showed at the Freer Gallery on Thursday night. Cage was on the program, of course — his “String Quartet in Four Parts” is as transcendentally gorgeous now as it was in 1950 — but the spotlight was on works by four intriguing, if relatively unknown, Asian American composers. Kee Yong ChongFirst up was Kee Yong Chong’s “Clouds Surging” — an atmospheric work in every sense. Arranging themselves around the room like the four winds, the Momenta players unleashed an utterly abstract, utterly beautiful sonic skyscape that seemed to reveal the inner life of clouds. Built almost entirely from airy, weightless textures, its scratches and whispers and delicate wisps of sound seemed to form, evaporate and appear again in constantly changing shapes with all the relentless inventiveness of nature. An extraordinary musical experience — you felt you were floating the entire time — and a fine new work.

Kee Yong ChongFirst up was Kee Yong Chong’s “Clouds Surging” — an atmospheric work in every sense. Arranging themselves around the room like the four winds, the Momenta players unleashed an utterly abstract, utterly beautiful sonic skyscape that seemed to reveal the inner life of clouds. Built almost entirely from airy, weightless textures, its scratches and whispers and delicate wisps of sound seemed to form, evaporate and appear again in constantly changing shapes with all the relentless inventiveness of nature. An extraordinary musical experience — you felt you were floating the entire time — and a fine new work.

Ushio Torikai’s “Four Teen,” which followed, opened with such determined gravity that the Freer felt as if it were crashing suddenly to Earth. But Torikai is among the most gifted female Japanese composers on the planet, and the work (based on her visit to a Zen garden in Kyoto) proved to be strikingly original, satisfyingly complex and altogether absorbing. Huang Ruo’s “The Flag Project” — inspired by Himalayan prayer flags — didn’t impress as much. It may have been the tinkly-winkly Tibetan finger cymbals, or the po-faced, more-Buddhist-than-thou feel of the thing; either one was enough to undermine its impact.

Things picked up again with the cheerfully postmodern “If We Live in Forgetfulness, We Die in a Dream,” a recent work by Jason Hwang. Its connection with Buddhism was maybe more theoretical than musical, but it was a warm, human, richly melodic work with all the finely tuned eclecticism we’ve come to expect from Hwang (who brought his extraordinary “Burning Bridge” suite to the Freer two years ago). It was Cage, though — the old master — who stole the show. His “Quartet” is a work of such profound tranquillity that it sounds like it came from another plane of existence entirely, and the Momenta players gave it a reading Cage would have loved: dry, spare, uninflected and free of anything but its own sound.

PostClassical Ensemble at the National Gallery of Art

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • November 5, 2012

There was a sizable Russian contingent in both the audience and the orchestra at the National Gallery of Art on Sunday night; not surprising, perhaps, given that it was the closing concert of the PostClassical Ensemble’s three-week festival devoted to Dmitri Shostakovich, the brilliant and controversial composer who was either a closet opponent or a passive supporter of the oppressive Soviet regime under which he worked. And it was, in every respect, a fascinating and compelling evening. The PostClassical Ensemble is famous for its innovative performances — which mix different media with unusual repertoire — and Sunday night’s concert took a fresh look at contrasting sides of Shostakovich’s character, featuring rarely heard transcriptions for string chamber orchestra of two of the composer’s most personal string quartets.

And it was, in every respect, a fascinating and compelling evening. The PostClassical Ensemble is famous for its innovative performances — which mix different media with unusual repertoire — and Sunday night’s concert took a fresh look at contrasting sides of Shostakovich’s character, featuring rarely heard transcriptions for string chamber orchestra of two of the composer’s most personal string quartets.

The concert opened with the Chamber Symphony for Strings in C Minor, Op. 110a, the transcription by Rudolf Barshai of Shostakovich’s autobiographical eighth quartet. Beefing up a quartet to an ensemble five times as large is risky; delicate details get lost, and edge and agility are often sacrificed for power. But under the nuanced and utterly fluid direction of Angel Gil-Ordonez, the work lost none of its roiling, acrid bite nor its unearthly luminosity. The wild-eyed allegretto was as menacing as ever, the three largo movements even more sweeping and ethereal than in the quartet version, and concertmaster Oleg Rylatko brought off the lead violin lines with genuine ferocity and power. The quartet may be a whirlwind, but in these hands, the chamber version became a tornado.

A typically PostClassical touch followed, as a recording of Shostakovich himself playing his Prelude in C Major drifted, ghost-like, from speakers high in the hall. Pianist George Vatchnadze then took the stage to play the same work (with its accompanying Fugue) as well as the Prelude and Fugue in G minor, providing an island of calm and transcendent clarity before the closing work, the Chamber Symphony for Strings in A-flat Major, Op. 118a (from the 1964 string quartet No. 10). Beautifully played, with a wonderfully scherzo-like allegro furioso and a profound, deeply moving adagio passacaglia, it proved to be a work of stunning power and grace — perhaps even more beautiful than the original version for quartet.

Midori at the Terrace Theater

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • November 2, 2012

The violin superstar Midori — who burst onto the world stage at 14 and still, decades later, seems saddled with the “prodigy” label — maintains the driving concert schedule of a celebrity, playing major concertos in one huge hall after another. So it was a rare opportunity to hear her in the more intimate setting of the Kennedy Center’s Terrace Theater on Thursday night, when she offered up a mostly Beethoven recital (with pianist Ozgur Aydin) that promised to be a more personal — and maybe even revelatory — glimpse into the heart of this notoriously private musician. Or . . . possibly not. Midori played three of Beethoven’s violin sonatas, interwoven with 20th-century works by Anton Webern and George Crumb, and played with consummate musicianship but a kind of keep-your-distance professionalism almost the entire time. She opened with Beethoven’s Violin Sonata No. 2 in A, Op. 12 No. 2 — a work so mincingly agreeable you almost felt embarrassed for the composer — and Midori and Aydin gave it a reading full of sunshine, curtsies and pasted smiles. The Violin Sonata No. 6 in A, Op. 30 No. 1 had more blood in its veins, but it was played with a kind of calculated, impenetrable polish that left you impressed but oddly unmoved.

Or . . . possibly not. Midori played three of Beethoven’s violin sonatas, interwoven with 20th-century works by Anton Webern and George Crumb, and played with consummate musicianship but a kind of keep-your-distance professionalism almost the entire time. She opened with Beethoven’s Violin Sonata No. 2 in A, Op. 12 No. 2 — a work so mincingly agreeable you almost felt embarrassed for the composer — and Midori and Aydin gave it a reading full of sunshine, curtsies and pasted smiles. The Violin Sonata No. 6 in A, Op. 30 No. 1 had more blood in its veins, but it was played with a kind of calculated, impenetrable polish that left you impressed but oddly unmoved.

Midori’s cool professionalism worked to better advantage, though, in the modern works on the program. She made Webern’s laconic, miniature Four Pieces for Violin and Piano, Op. 7 as perfect and infinitely mysterious as one of Joseph Cornell’s famous boxes, and the Four Nocturnes by Crumb was also beautifully done, full of exotic timbral effects from violin and piano that evoked fraught whispers, disturbing dreams and the menacing things that seem to prowl Crumb’s unquiet nights.

All of this, though, was just prelude to the climax of the evening, Beethoven’s great “Kreutzer” Sonata, Op. 47. Midori turned in a bravura performance of this exhilarating work, head lowered as if charging into a hurricane, and captured the rough, sweeping drama of the thing. Maybe it didn’t have the savage intensity of Patricia Kopatchinskaja’s game-changing 2008 recording of the work, but it drew more out of Midori than mere virtuosity — and gave us a brief, intriguing glimpse into the woman behind the gloss.

Michael Brown at the Phillips Collection

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • October 29, 2012

With Hurricane Sandy hard on his heels, the up-and-coming young pianist Michael Brown blew into town on Sunday afternoon for a recital at the Phillips Collection, standing in at the last minute for pianist Leon McCawley, who had canceled because of illness. Brown made the most of the opportunity, presenting an eclectic and often revealing program that ranged from Schubert to the sophisticated modernism of George Perle — with a work by Brown himself at center stage.

Much of the first half of the program had a distinctly Spanish flavor. Brown opened with Isaac Albéniz’s “El Puerto” from the well-known “Suite: Iberia”, and it was immediately clear that Brown favors a direct, robust approach to the piano, full of vivid colors and and gestures chiseled in stone. That approach worked beautifully in works like Perle’s clever, extroverted “Toccata” from 1969 (which Brown played with verve and obvious affection) but wasn’t quite as convincing in Debussy’s luminous “La Soirée dans Grenade” (from Estampes) and Ravel’s “Alborada del gracioso” from “Miroirs.’ Both works live and breathe on their delicate nuances and fine shadings of color; too much power and their light just seems to blink out.

Much of the first half of the program had a distinctly Spanish flavor. Brown opened with Isaac Albéniz’s “El Puerto” from the well-known “Suite: Iberia”, and it was immediately clear that Brown favors a direct, robust approach to the piano, full of vivid colors and and gestures chiseled in stone. That approach worked beautifully in works like Perle’s clever, extroverted “Toccata” from 1969 (which Brown played with verve and obvious affection) but wasn’t quite as convincing in Debussy’s luminous “La Soirée dans Grenade” (from Estampes) and Ravel’s “Alborada del gracioso” from “Miroirs.’ Both works live and breathe on their delicate nuances and fine shadings of color; too much power and their light just seems to blink out.

Brown’s technique is impressive, though, and he showed it off to fine advantage in Schubert’s fast-paced Sonata in D Major, D. 850, turning in a reading that was long on muscle if a bit short on tenderness. But it was the pianist’s own “Constellations and Toccata” that revealed the most about him. The work had received a stunning performance by Orion Weiss at the Terrace Theater back in January, but Brown’s own performance (from a score he read off an iPad on the piano) was exceptionally beautiful, from the spare, nocturne-like opening to the explosive toccata that closes it.

Musicians from Marlboro at the Freer Gallery

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • October 26, 2012

What is it about Haydn’s string quartets that we love so much? Is it the headlong rush of endorphins to the brain they provoke? Or the sense that the universe — despite all evidence — is a warm, well-ordered and fundamentally happy place? Who knows; suffice it to say that Thursday night’s concert by Musicians from Marlboro at the Freer Gallery opened with a performance of Haydn’s String Quartet in A, Op. 55, No. 1 that was so fresh and full-blooded, so full of earthy vitality and sheer sensual pleasure, that it made you happy to be alive — even in election season. Soovin KimMusicians from Marlboro is the touring ensemble of young professionals brought together at the venerable Marlboro Music Festival in southern Vermont every summer, and its members are among the best of the best young players in the country. This year’s crop includes the gifted violinist Soovin Kim, who — with the equally fine Benjamin Jaber on horn and Matan Porat at the piano — turned in an extraordinarily powerful reading of the Trio for Violin, Horn and Piano by Gyorgi Ligeti. It’s an homage of sorts to Brahms, and there is something Brahmsian in the golden, murmuring warmth of the opening “Andante con tenerezza.” But Ligeti soon turns toward his own dark and unsettling depths, from the slightly unhinged jauntiness of the “Vivacissimo molto ritmico” to the rough, herky-jerky “Alla marcia,” which sounds like nothing so much as marionettes being jerked around by some demented god. And all that is mere prelude to the wrenching “Lamento,” which closes the work — a searing, unblinking stare into anguish that tears the heart to shreds. An absolutely riveting piece and an unforgettable performance.

Soovin KimMusicians from Marlboro is the touring ensemble of young professionals brought together at the venerable Marlboro Music Festival in southern Vermont every summer, and its members are among the best of the best young players in the country. This year’s crop includes the gifted violinist Soovin Kim, who — with the equally fine Benjamin Jaber on horn and Matan Porat at the piano — turned in an extraordinarily powerful reading of the Trio for Violin, Horn and Piano by Gyorgi Ligeti. It’s an homage of sorts to Brahms, and there is something Brahmsian in the golden, murmuring warmth of the opening “Andante con tenerezza.” But Ligeti soon turns toward his own dark and unsettling depths, from the slightly unhinged jauntiness of the “Vivacissimo molto ritmico” to the rough, herky-jerky “Alla marcia,” which sounds like nothing so much as marionettes being jerked around by some demented god. And all that is mere prelude to the wrenching “Lamento,” which closes the work — a searing, unblinking stare into anguish that tears the heart to shreds. An absolutely riveting piece and an unforgettable performance.

The players regrouped for Mendelssohn’s String Quintet No. 1 in A, Op. 18, a rapturous work written a year after the famous Octet — when the composer was still in his teens — and nearly as miraculous. The Marlboro players, led by Itamar Zorman on violin, turned in a performance so light and graceful it was nearly weightless, with detailed and utterly transparent playing.

Academy of St Martin in the Fields Chamber Ensemble at George Mason

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • October 22, 2012

The Academy of St. Martin in the Fields is one of those orchestras so well-known that it’s become a modern musical icon, its name synonymous with impeccable musicianship, irreproachable British taste and performances so polished that they fairly gleam. There are several permutations of the group, and eight of its string players — who make up the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields Chamber Ensemble — arrived at George Mason University’s Center for the Arts on Sunday for an afternoon of mostly Romantic-era music that lived up to, and maybe even surpassed, the hype.

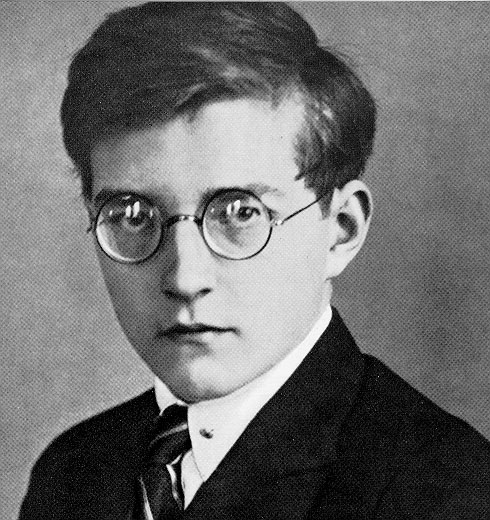

Led by violinist Thomas Bowes, the players opened with Johannes Brahms’s String Sextet No. 2 in G major, Op. 36. It’s a lush and deeply felt work — Brahms wrote it, the story goes, as a sort of farewell to his great love Agathe von Siebold — and the group approached it with tenderness and restraint, letting the music’s deep dramatic lines unfold in a deliberately paced, utterly natural way. Their sound is sweet and pure, their ensemble work airtight, and the playing purred along effortlessly. Even if you find Brahms a little long-winded at times — as some among us do — when his music is played this elegantly, you really don’t mind. The young ShostakovichThe next two pieces on the program formed an intriguing pair: octets written exactly 100 years apart, both by composers still in their teens, and each the diametric opposite of the other. Dmitri Shostakovich was only 18 when he wrote his 1925 Prelude and Scherzo for String Octet, Op. 11, and it’s a shockingly accomplished piece, brash and spiky and modernist and already full of the composer’s trademark bite. The ensemble gave it a brilliant performance, with edges so sharp that you could almost cut yourself on them.

The young ShostakovichThe next two pieces on the program formed an intriguing pair: octets written exactly 100 years apart, both by composers still in their teens, and each the diametric opposite of the other. Dmitri Shostakovich was only 18 when he wrote his 1925 Prelude and Scherzo for String Octet, Op. 11, and it’s a shockingly accomplished piece, brash and spiky and modernist and already full of the composer’s trademark bite. The ensemble gave it a brilliant performance, with edges so sharp that you could almost cut yourself on them.

The contrast could not have been greater with Felix Mendelssohn’s warm and embracing Octet for Strings in E-flat major, Op. 20, written in 1825, when the composer was 16. It’s often referred to as a musical miracle, and the description is apt: Not only is the thing absolutely captivating from beginning to end, but in its sweeping, symphonic scope, it feels like the work of a completely mature composer. The ensemble played it with obvious pleasure, turning in a luminous and often-breathtaking performance that won the musicians a standing ovation.

Great Noise Ensemble at the Atlas

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • October 21, 2012

Is the Atlas Performing Arts Center — at the heart of D.C.’s designated hipster zone on H Street Northeast — fast becoming the city’s center for cutting-edge music? That seems to be the goal of Atlas Music Director Armando Bayolo. He’s bringing some of the biggest guns in new music to town this season — including So Percussion, Maya Beiser and the International Contemporary Ensemble — and on Friday night he showcased his own Great Noise Ensemble in a wild and sometimes woolly program titled “Irreverence,” featuring music inspired by insectivorous plants, a hyperkinetic chamber symphony from John Adams and a kind of profane pop oratorio by Bayolo himself — in which God, at a climactic moment, yells at Adam: “You could have lived in Paradise! Why couldn’t you keep your [expletive] mouth shut?”

An appealing new quartet by Jonathan Newman kicked off the concert. It’s titled, unforgettably, “These Inflected Tentacles.” It’s a dicey-sounding title, but the work is actually built on Charles Darwin’s 19th-century accounts of dropping glass, hair and other bits of stuff into Venus’ flytraps (back when science was fun!) to see how they would react.

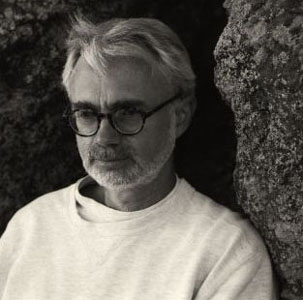

Newman’s piece turned out to be very engaging, if more gentle and dance-like than carnivorous. It was hard to escape the “under-rehearsed” feeling, though: The players were shunted to auditory Siberia on the distant left edge of the stage, the title of the wrong piece was projected over them in big letters and the music’s rhythmic difficulties — the meter seemed to shift every bar or so — required a conductor just to hold the four musicians together. The performance never really felt sure of itself, and the electricity never quite flowed. John AdamsBut John Adams’s “Son of Chamber Symphony” from 2007 brought things into focus. It’s a playful title for a playful work and shares the same musical DNA as Adams’s now-classic “Chamber Symphony” of 1992, with sly references here and there to “Harmonielehre,” “Nixon in China” and other early Adams works. Brilliantly orchestrated for 15 players, “Son” is full of color and wit and an almost slapstick, cartoonish sense of movement. Conductor David Vickerman gave it a fine if rather straightforward performance, played more or less mezzo-forte from top to bottom and not as clearly delineated as you might hope, but still hugely enjoyable.

John AdamsBut John Adams’s “Son of Chamber Symphony” from 2007 brought things into focus. It’s a playful title for a playful work and shares the same musical DNA as Adams’s now-classic “Chamber Symphony” of 1992, with sly references here and there to “Harmonielehre,” “Nixon in China” and other early Adams works. Brilliantly orchestrated for 15 players, “Son” is full of color and wit and an almost slapstick, cartoonish sense of movement. Conductor David Vickerman gave it a fine if rather straightforward performance, played more or less mezzo-forte from top to bottom and not as clearly delineated as you might hope, but still hugely enjoyable.

Bayolo’s “Sacred Cows” is built on the intriguing idea of using a sort of oratorio to explore the loss of religious belief. Bayolo’s own faith, he told the audience, had “evaporated in a cloud of logic” once he began to seriously study Christianity a decade ago, and “Cows” reflects a range of complex emotions from bitterness and anger to questioning regret, couched in an often jazzy, secular musical language. Not always an easy listen, and some of the text (“sacred cows make the best hamburger”) could induce cringing, but it was an unusual and provocative work nevertheless, from one of this city’s most hardworking composers.