Charlie Albright at the Phillips Collection

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • October 15, 2012

It’s hard not to like Charlie Albright, the gifted young pianist who’s been racking up coast-to-coast awards over the past few years. At 24, he emanates a kind of appealing nerd chic: that baby face and anime hair, those glasses sliding constantly down his nose, the coltish stage presence and the degree in economics from Harvard. Little wonder that when he stepped onstage at the Phillips Collection on Sunday, a wave of maternal cooing swept through the crowd. But as he launched into a program of Beethoven and Chopin, Albright’s raw power at the keyboard quickly became clear. He dispatched Beethoven’s Sonata No. 31 in A-Flat, Op. 110, with a kind of rough, even brutal directness, refreshing in its clarity but not always particularly nuanced. He seemed to be shooting for excitement rather than depth; a fast-paced, “the-hell-with-subtlety” approach that goosed up the drama in the second and final movements but left the love-drenched opening arid and pale.

But as he launched into a program of Beethoven and Chopin, Albright’s raw power at the keyboard quickly became clear. He dispatched Beethoven’s Sonata No. 31 in A-Flat, Op. 110, with a kind of rough, even brutal directness, refreshing in its clarity but not always particularly nuanced. He seemed to be shooting for excitement rather than depth; a fast-paced, “the-hell-with-subtlety” approach that goosed up the drama in the second and final movements but left the love-drenched opening arid and pale.

Albright’s keyboard skills are spectacular, and he takes obvious pleasure in unleashing them. But by the end, you felt as if you’d spent 20 minutes wading in turbulent shallows and had only gotten wet to the knees.

The 12 finger-snarling etudes of Chopin’s Op. 25 fared about the same: exhilarating keyboard work and a wonderful sense of vitality, structure and purpose, but painted in bright colors rather than complex hues, with every contrast underscored and underscored again. The effect was to turn many of these elusive, mysterious little pieces into entertainment — to shine so much daylight into their depths that their magic evaporated and was gone. And what is Chopin without magic?

Albright closed with an encore that might have been written for him: Arcadi Volodos’s wild transcription of the “Alla Turca” movement of Mozart’s Piano Sonata No. 11. It’s a supersonic, delirious ride around the keyboard, and Albright tossed it off with casual, near-perfect ease.

Sphinx Virtuosi at the Kennedy Center

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • October 11, 2012

The gifted young musicians known as the Sphinx Virtuosi are an intriguing group: They’re all laureates of the Sphinx Competition for young black and Latino string players, which is dedicated to developing diversity in classical music. They arrived at the Terrace Theater on Wednesday night as part of the Fortas Chamber Music series and presented a program of largely Latin American music that was beautifully played — and, frankly, a refreshing counterpoint to the pallid menu of Bruckner, Beethoven and other low-risk composers being wholesaled at the Kennedy Center this season.

In fact, some of the most fiery and flavorful music of the past century has come out of Latin America, and the Sphinx players (joined by the Catalyst Quartet) made a good case for bringing more of it into the mainstream. It might have been a mistake to open with Heitor Villa-Lobos’s drippy, Europe-aping “Suite for Strings,” but the ensemble dispatched it with reasonable haste and taste and quickly moved on to meatier fare.

Cellist Gabriel Cabezas got the adrenaline flowing with a furious, loose-limbed performance of “Moto Perpetuo,” from “Lamentations for Solo Cello” by African American composer Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson, and the Catalyst Quartet took the stage for Osvaldo Golijov’s “Tenebrae.” It’s a meditative work whose floating mists and cosmic ambiguities can, in the wrong hands, seem like music to do yoga by, but the Catalyst players turned in a serious, convincing account. Elena UriosteThe tone shifted from dark to light when the quartet launched into “Strum,” a hugely enjoyable new work by Sphinx violinist Jessie Montgomery. Turbulent, wildly colorful and exploding with life, “Strum” sounded like a handful of American folk melodies tossed into a strong wind, cascading and tumbling joyfully around one another. Montgomery also wrote the evening’s encore, “Star-burst”; at 30, she’s an inventive and appealing composer with interesting things ahead of her.

Elena UriosteThe tone shifted from dark to light when the quartet launched into “Strum,” a hugely enjoyable new work by Sphinx violinist Jessie Montgomery. Turbulent, wildly colorful and exploding with life, “Strum” sounded like a handful of American folk melodies tossed into a strong wind, cascading and tumbling joyfully around one another. Montgomery also wrote the evening’s encore, “Star-burst”; at 30, she’s an inventive and appealing composer with interesting things ahead of her.

An electrifying performance of Alberto Ginastera’s “Finale Furioso” from his Concerto for Strings closed the concert, but it was the “Four Seasons of Buenos Aires” by the Argentine composer Astor Piazzolla that really stole the show. Or rather, it was violin soloist Elena Urioste who stole it. A drop-dead beauty who plays with equal parts passion, sensuality, brains and humor, Urioste tossed off the work’s captivating tangos and sly quotes of Vivaldi almost flirtatiously, as the Sphinx players provided precise and electrical accompaniment. It was an exciting and virtually flawless performance that brought the audience to its feet.

Mak Grgic and Stephen Ackert at the National Gallery of Art

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • October 8, 2012

In a more enlightened, just and fair-minded world, the music of Sylvius Leopold Weiss would not be as shamefully neglected as it is. This baroque lutenist and sort-of pal to J.S. Bach wrote reams of extremely high-end music for the lute — some of it, to these ears, nearly as perfect as Bach’s — so it was a treat to hear the Slovenian guitarist Mak Grgic spotlight two rarely heard works by Weiss in a fine performance of Renaissance and Baroque music on Sunday night at the National Gallery of Art.

At 25, Grgic is at the beginning of his career, but he proved himself a lyrical, insightful player throughout the evening. The program — tied loosely to the gallery’s exhibit “Imperial Augsberg: Renaissance Prints and Drawings 1475-1540” — ranged from 15th-century songs by Heinrich Isaac to 18th-century works from Adam Falckenhagen, and showcased Grgic’s thoughtful and delicately nuanced approach. Grgic seems to favor beauty over electricity, and was at his best in quiet, introspective works such as Giovanni Girolamo Kapsberger’s “Toccata No. 6”, which opened the program, and three colorful Fantasias by Francesco da Milano.

At 25, Grgic is at the beginning of his career, but he proved himself a lyrical, insightful player throughout the evening. The program — tied loosely to the gallery’s exhibit “Imperial Augsberg: Renaissance Prints and Drawings 1475-1540” — ranged from 15th-century songs by Heinrich Isaac to 18th-century works from Adam Falckenhagen, and showcased Grgic’s thoughtful and delicately nuanced approach. Grgic seems to favor beauty over electricity, and was at his best in quiet, introspective works such as Giovanni Girolamo Kapsberger’s “Toccata No. 6”, which opened the program, and three colorful Fantasias by Francesco da Milano.

But there were more playful moments, as well. Grgic was joined by organist Stephen Ackert, who heads up the gallery’s music department, for an amiable little lute concerto in F Major by Karl Ignaz Augustin Kohaut. Ackert was playing a sort of miniature pipe organ known as a portative, and its pint-size sound worked surprisingly well with the guitar; a smile-inducing work all around.

But it was in the music of Weiss that the guitarist seemed most assured, and his skills most evident. He turned in a beautiful account of Weiss’s six-movement “L’Infidel” suite, exploring its contrasts and fascinating twists and turns — from the deeply personal Sarabande to the slow-gathering power of the Paisanne — with real intelligence. And Weiss’s Passacaglia in D Major (a masterwork if there ever was one) may have been the high point of the evening; a superb, finely detailed reading that showed Grgic is a guitarist to keep an eye on.

Verge Ensemble at the Corcoran Gallery

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • September 24, 2012

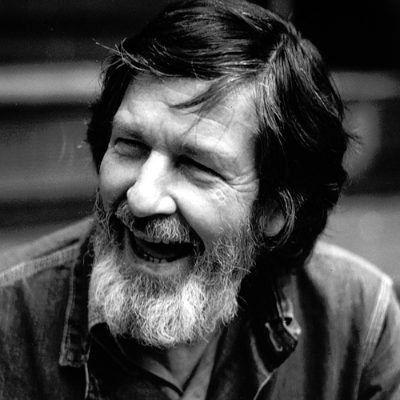

The small but determined Verge Ensemble — the Washington-based new music group for whom the term “plucky” might have been invented — opened its 2012/2013 season on Sunday afternoon at the Corcoran Gallery. It was a fascinating program, contrasting different approaches to notating music — from the highly specific to the dauntingly vague — and underscoring the role that performers themselves play in the realization of a composer’s ideas. Earle BrownThe program opened with two barely notated works from the early 1950s, Morton Feldman’s “Intersection IV” for solo cello and Earle Brown’s “December, 1952.” No pitch or rhythm or even style is given in either piece; they’re sketches, frameworks for performers to fill in with their own ideas, and that seemed to suit the Verge players just fine. Cellist Steven Honigberg turned in a wonderfully colorful and lively account of the Feldman — a composer not particularly renowned for liveliness — and was joined by violinist Jonathan Richards and violist James Stern for an interpretation of the Brown that was so lush and rhapsodic it almost seemed to mock the spare graph of dots and dashes that make up the score.

Earle BrownThe program opened with two barely notated works from the early 1950s, Morton Feldman’s “Intersection IV” for solo cello and Earle Brown’s “December, 1952.” No pitch or rhythm or even style is given in either piece; they’re sketches, frameworks for performers to fill in with their own ideas, and that seemed to suit the Verge players just fine. Cellist Steven Honigberg turned in a wonderfully colorful and lively account of the Feldman — a composer not particularly renowned for liveliness — and was joined by violinist Jonathan Richards and violist James Stern for an interpretation of the Brown that was so lush and rhapsodic it almost seemed to mock the spare graph of dots and dashes that make up the score.

Andrew NormanTraditionally notated works by two of America’s most engaging composers followed. Jeffrey Mumford can always be counted on for probing, intensely moving music, and Stern brought out all the dark beauty of “wending,” a 2001 piece for solo viola. The music of Augusta Read Thomas rarely fails to delight the ears, and “Bells Ring Summer” for solo cello was no exception — a gorgeous work with all the open-air exuberance of a carillon.

Andrew NormanTraditionally notated works by two of America’s most engaging composers followed. Jeffrey Mumford can always be counted on for probing, intensely moving music, and Stern brought out all the dark beauty of “wending,” a 2001 piece for solo viola. The music of Augusta Read Thomas rarely fails to delight the ears, and “Bells Ring Summer” for solo cello was no exception — a gorgeous work with all the open-air exuberance of a carillon.

But perhaps the most spectacular music of the afternoon came in “The Companion Guide to Rome,” a beautifully drawn suite for string trio by the young and wildly gifted composer Andrew Norman. It’s a series of nine “portraits” of various churches across Rome, and it ranges from the explosive ecstasy of the opening “Teresa” to the ethereal weightlessness of “Ivo,” the ghostly fragility of “Clemente” and the exalting, jaw-dropping brilliance of the closing “Sabina.” Norman brings it all off with exceptional imagination and a very deft touch, and the Verge players played it with a sense of communion that was utterly convincing.

John Cage Centennial Festival at the National Gallery of Art

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • September 11, 2012

The John Cage Centennial Festival, which has brought some of the 20th century’s most provocative music to Washington over the past week, had its final concert on Sunday night in the Atrium of the National Gallery of Art’s East Building. Margaret Leng Tan and John CageIt was a fittingly cathedral-like place for the event; Cage changed how we think about music in fundamental ways, and the concert brought together some of his most iconic and pathbreaking work, embodying innovations from the use of chance to the invention of the “prepared piano.”

Margaret Leng Tan and John CageIt was a fittingly cathedral-like place for the event; Cage changed how we think about music in fundamental ways, and the concert brought together some of his most iconic and pathbreaking work, embodying innovations from the use of chance to the invention of the “prepared piano.”

“Imaginary Landscape No. 4” — a piece as enigmatic as it sounds — opened the evening. It’s one of Cage’s early forays into indeterminacy, where the structure of the work is precisely determined but the content left to chance. It’s a dicey way to make music, but as members of the National Gallery of Art New Music Ensemble tweaked the dials of a dozen different radios, wave after wave of random words, static and snatches of song — the ocean of sound we swim in every day, but barely notice — rose and fell and rose again in a rapturous flow. The piece was played too quietly, alas; the cavernous Atrium eats little radios for lunch, and you almost had to strain to hear.

But Cage’s “Cartridge Music,” another iconic work from 1960, kicked things into high gear. Using a computer-generated score realized by the estimable young composer Jaime Oliver, three players manipulated electronics and amplified tiny objects to unleash a colorful, even joyful universe of sound. Plastic toys skittered, Slinkies boinged happily up and down, combs were plucked and pencils scratched; a virtuosically playful performance in every sense. Roger ReynoldsThe rest of the evening stayed at that exhilarating level, though Cage’s “Ryoanji,” which closed the program, was a bit of a trial. It’s one of the composer’s most austere, pared-down works — you need to be a Zen monk to really appreciate it properly — and minds were visibly wandering by the end.

Roger ReynoldsThe rest of the evening stayed at that exhilarating level, though Cage’s “Ryoanji,” which closed the program, was a bit of a trial. It’s one of the composer’s most austere, pared-down works — you need to be a Zen monk to really appreciate it properly — and minds were visibly wandering by the end.

But five pieces by other composers were uniformly stunning, from Roger Reynolds’ stark, urgent “OPPOrTuniTy” (played and sung-shouted by pianist Margaret Leng Tan), to George Lewis’s cheerfully postmodern “Merce and Baby.” Jenny Lin — surely one of the most interesting pianists in America right now — stormed through Steve Antosca’s ritualistic “evocation,” stirring up a nest of spirits who, in a spine-tingling coda, she then drew from the depths of the piano with lengths of string between the wires.

The high point of the concert, though, may have been Stephen Drury’s reading of music Cage wrote for a 1950 film about the sculptor Alexander Calder. It’s luminous, unabashedly beautiful stuff (yes, much of Cage is very beautiful) written for a piano “prepared” to evoke the sound of muffled gongs. Drury played with eloquent simplicity, allowing the music to unfold with a kind of weightless grace, rising upward toward the immense Calder mobile that, impassive and inscrutable as the universe, turned slowly above our heads.

Alexis Descharmes at the Cage Centennial Festival

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • September 6, 2012

The volcanically innovative composer/writer/artist John Cage — whose legacy is being celebrated across Washington this week in a not-to-be-missed festival of concerts, lectures and exhibits — would have been 100 years old Wednesday night, and to mark the event the French cellist Alexis Descharmes and a stellar cast of friends put on a tribute to the composer at La Maison Francaise. It was, in fact, a very Cageian evening, integrating the composer’s music with visual art, the spoken word, a bit of theater, and the work of other musicians who influenced and were influenced by Cage himself. John CageDescharmes opened the evening by entering a pitch-black stage and, in a quiet tribute to Cage, lighting a flame and launching into the “Solo for Cello” from 1957-58. The piece is quintessential Cage; a succession of spare, beautiful sounds that emerge out of silence, float for a moment and vanish. It’s music pared away to sound itself, purified of narrative or emotion or contrived human drama. Cage’s music isn’t easy; it needs to be met on its own dauntingly simple terms. But to do that is to discover music that’s utterly authentic, transcendent and full of a strange and almost unfathomable beauty.

John CageDescharmes opened the evening by entering a pitch-black stage and, in a quiet tribute to Cage, lighting a flame and launching into the “Solo for Cello” from 1957-58. The piece is quintessential Cage; a succession of spare, beautiful sounds that emerge out of silence, float for a moment and vanish. It’s music pared away to sound itself, purified of narrative or emotion or contrived human drama. Cage’s music isn’t easy; it needs to be met on its own dauntingly simple terms. But to do that is to discover music that’s utterly authentic, transcendent and full of a strange and almost unfathomable beauty.

To these ears, though, the impact was diminished by Descharmes’s curious decision to accompany the work with a soundtrack of a crackling wood fire. Kudos for boldness and all that, but Cage’s sound-world is based in silence perhaps more than that of any other composer, and the noise proved distracting more than illuminating. Similarly, Cage’s “Music for Two” (played with violinist Irvine Arditti), was brilliantly performed, but an overhead slideshow of art by Gerhard Richter kept demanding attention, and Cage, alas, just doesn’t work as music for multitasking. Alexis DescharmesThose quibbles aside, the concert was often illuminating. Erik Satie was a key influence on Cage, and the short, beguiling “Gnossiennes” and “Gymnopedies” — whose melodies seem to float like mobiles in a breeze — were linked to Cage’s music throughout the evening. The Austrian composer Beat Furrer contributed a gorgeous, quiet, deep-moving tribute titled “ferner Gesang” (“distant song”) that had the weight of a sonic sculpture, and a worshipful letter from Pierre Boulez to John Cage was read aloud, the young Boulez urging Cage to remain “elusive” as long as possible. Another tribute, Klaus Huber’s “. . . ruhe sanft. . .” (“. . . rest gently . . .”), written shortly after Cage’s death in 1992, was a poignant if sometimes creepy work that used amplified breathing sounds and the name “John” repeated in a questioning voice.

Alexis DescharmesThose quibbles aside, the concert was often illuminating. Erik Satie was a key influence on Cage, and the short, beguiling “Gnossiennes” and “Gymnopedies” — whose melodies seem to float like mobiles in a breeze — were linked to Cage’s music throughout the evening. The Austrian composer Beat Furrer contributed a gorgeous, quiet, deep-moving tribute titled “ferner Gesang” (“distant song”) that had the weight of a sonic sculpture, and a worshipful letter from Pierre Boulez to John Cage was read aloud, the young Boulez urging Cage to remain “elusive” as long as possible. Another tribute, Klaus Huber’s “. . . ruhe sanft. . .” (“. . . rest gently . . .”), written shortly after Cage’s death in 1992, was a poignant if sometimes creepy work that used amplified breathing sounds and the name “John” repeated in a questioning voice.

Descharmes was accompanied brilliantly throughout the evening by pianist Jenny Lin, clarinetist Bill Kalinkos and violinist Lina Bahn. But the high point of the evening may have been when percussionist Steven Schick joined the cellist for Cage’s “Etudes Boreales” from 1978. Using the piano body and strings as percussion devices, Schick played with extraordinary precision and electricity, and the work burst spectacularly into life — as fine a performance of Cage as you could hope to hear.

Old Instruments Suffer in the Breakneck Modern World

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • August 19, 2012

It was a warm evening in early June, and an early-music ensemble called The Vivaldi Project had just begun a concert of Baroque music at St. George’s Episcopal Church in Arlington. Enthusiastic applause broke out as the group finished a sonata by Arcangelo Corelli, and much of it seemed aimed at William Simms, who was performing that night on the theorbo — an odd-looking instrument something like a lute, but with a long, delicate neck extending some five feet beyond its body.

As the applause faded, Simms began to retune his instrument for the next piece, when suddenly a loud crack — as harsh and unsettling as a gunshot — rang through the room. Simms slowly lifted his theorbo into the air. Under the tension of its fifteen strings, the instrument’s graceful neck had snapped in two, and now hung there limply, like a broken limb. Simms could only stare at it in shock.

As the applause faded, Simms began to retune his instrument for the next piece, when suddenly a loud crack — as harsh and unsettling as a gunshot — rang through the room. Simms slowly lifted his theorbo into the air. Under the tension of its fifteen strings, the instrument’s graceful neck had snapped in two, and now hung there limply, like a broken limb. Simms could only stare at it in shock.

“It’s just a horrifying thing when an instrument breaks — this terrible feeling of despair goes through you,” says Constance Whiteside, one of the organizers of the concert. “We ran back to see if we could fix it, but there was nothing we could do.”

Simms was sidelined for the rest of the concert, but was able to get his theorbo to a specialist the next day and was back on stage with it within a week. But as it turns out, classical instruments — particularly the oldest and most valuable — fall apart or are damaged with surprising frequency. Or perhaps it’s not all that surprising. Most classical instruments, particularly the stringed ones, are rather delicate, and were designed well over a hundred years ago. Many were never intended to last a long time, let alone survive the international travel, crowded stages, sudden changes in humidity and other indignities of the modern concert world. Talk to any musician and you’re sure to hear stories of flutes being knocked over, basses dropped into orchestra pits, guitars crushed by airlines and harps disintegrating under the pull of their own strings.

And when it happens, it can be devastating.

“I was playing a concert a few years ago,” says Stephanie Vial, a cellist with the Atlanta Baroque Orchestra, “and during the break they put a small podium on stage. I had taken my cello out of its case, and was holding it in such a way that I couldn’t see the podium. I had no idea it was there, and I just tripped on it and started to fall. I couldn’t stop myself — and I ended up on top of the instrument.”

Vial’s cello — a rare, $60,000 instrument built in 1770 by William Forster — seemed ruined, with a ragged hole running up its right side and the bridge smashed in. “I thought I had destroyed it,” she says. “I just sat there holding it, sobbing, until one of my colleagues took it out of my hands. I kept telling myself, ‘It’s not one of my kids’ — but it was close. That cello is my voice.” Stephanie VialVial isn’t the only musician to fall on his or her instrument. Violin prodigy David Garrett tumbled down a flight of stairs in 2008, smashing his priceless Guadagnini, and countless other instruments have been dropped, sat on and left in taxis. Many can be restored, though the process is time-consuming and expensive; like Simms, Vial was eventually able to get her instrument rebuilt, though it took four months and many thousands of dollars. (It now sounds, she says, better than ever.)

Stephanie VialVial isn’t the only musician to fall on his or her instrument. Violin prodigy David Garrett tumbled down a flight of stairs in 2008, smashing his priceless Guadagnini, and countless other instruments have been dropped, sat on and left in taxis. Many can be restored, though the process is time-consuming and expensive; like Simms, Vial was eventually able to get her instrument rebuilt, though it took four months and many thousands of dollars. (It now sounds, she says, better than ever.)

But even without a dramatic accident, stringed instruments — whose delicate bodies must support the tremendous tension of their strings — are inherently fragile and susceptible to injury.

“There’s a fine edge between creating an instrument that has the best possible sound, and an instrument that is going to stay sturdy over the stresses of being played,” says Constance Whiteside. “The soundboard is where all the beauty of the sound of the instrument is. The thinner it is, the more beautiful — but also the more likely to just implode.”

Whiteside, one of the world’s most eminent early-music harp specialists, speaks from experience. At the Amherst Early Music Festival a few years ago, she was getting ready to perform a baroque opera with fellow harpist Andrew Lawrence King when she noticed something was amiss with her 52-string harp, an instrument so rare there was only one other like it in the world.

“I started hearing this weird sound, so I checked my harp,” she says, “and the seams were starting to separate! I turned to Andrew, and he just said, ‘duct tape.’ It sounds unbelievable, but we ran out and found some duct tape, and wrapped it around the instrument. Amazingly, the sound was still good.”

But of all the threats instruments face, nothing provokes as much dread — and anger — from musicians as air travel. Stories about crushed and mutilated instruments abound, including the time Polish pianist Krystian Zimerman had his Steinway destroyed by US Customs agents at JFK Airport in New York because they thought the piano “smelled funny.”

“We all live in fear of airlines,” says Constance Whiteside. “It doesn’t matter how good the case is, or what labels you put on it.” Like many musicians, she won’t travel with her harp unless it can go in the seat beside her.

Simms, in fact, suspects the crack in his theorbo may have resulted from rough handling just a few days earlier by a Transportation Security Administration inspector in San Francisco, as he was checking the instrument for a flight.

“She grabbed the instrument by its strings and yanked it out of its case,” says Simms, who watched helplessly from the sidelines. “And when she was done, she just pushed it off the table onto the conveyer belt, and it came crashing down — like dishes off a dining room table.”

“I’m never,” he says, “going to check an instrument again.”