Dar Williams and IBIS at the Spectrum

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • February 1, 2011

Dar Williams is a guitar-strumming pop-folk singer, known for her coffeehouse style and intensely personal songs. The IBIS Chamber Music Society is a sophisticated, highly polished classical ensemble. Doomed to live on separate planets -- or can the two find musical happiness together? Dar WilliamsThat was the question Sunday night at the Rosslyn Spectrum Theatre, when Williams and IBIS teamed up for an experiment in crossover. They met through family connections (Williams is the sister-in-law of IBIS founder Susan Robinson) and soon began to explore the idea of collaborating. Joseph Scheer, the group's violinist, arranged a number of Williams's songs for the six-member ensemble, and the family project was launched.

Dar WilliamsThat was the question Sunday night at the Rosslyn Spectrum Theatre, when Williams and IBIS teamed up for an experiment in crossover. They met through family connections (Williams is the sister-in-law of IBIS founder Susan Robinson) and soon began to explore the idea of collaborating. Joseph Scheer, the group's violinist, arranged a number of Williams's songs for the six-member ensemble, and the family project was launched.

Did it work? It was clear at Sunday's performance that this was a labor of love, with affection and mutual respect on all sides. IBIS opened with "Summerland," a luminous piece by the African American composer William Grant Still, before Williams came out with her guitar for "Calling the Moon." Williams is an engaging performer with one of those running-through-the-meadow voices, and she sang about a dozen of her more poignant songs - including "Blue Light of the Flame," "You're Aging Well" and her dark cover of Pink Floyd's "Comfortably Numb" - backed by the note-perfect IBIS ensemble playing Scheer's elegant, sophisticated arrangements.

And there's the rub. The power of Williams's songs comes from their intimacy; this is a confessional songwriter, above all else, who draws you in with her natural voice and open, warts-and-all honesty. Wryly funny and completely unaffected, Williams's strength is her directness. So, while Scheer's transcriptions were thoughtful and genuinely beautiful, the fit never seemed completely right - as if Williams were draped in jewels and a ball gown, trying desperately to keep it real.

Ariel Quartet at the Corcoran

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • January 31, 2011

The Ariel Quartet's members are no slouches; they work hard, and they crank out virtuosity by the bucketful and passion by the yard. Why, then, did their recital on Friday night at the Corcoran Gallery feel so curiously flat? The Ariel QuartetMaybe it was the wobbly start to the evening, when the Corcoran's technicians forgot to turn on the stage lights, leaving the hapless Ariel to play Beethoven's Quartet in D, Op. 18, No. 3 in the dim gloom. The opening Allegro of that engaging work should have brightened the place up a bit, but instead came off as lifeless and lacking in momentum, and the group didn't start generating electricity until the closing Presto. Better late than never, but still.

The Ariel QuartetMaybe it was the wobbly start to the evening, when the Corcoran's technicians forgot to turn on the stage lights, leaving the hapless Ariel to play Beethoven's Quartet in D, Op. 18, No. 3 in the dim gloom. The opening Allegro of that engaging work should have brightened the place up a bit, but instead came off as lifeless and lacking in momentum, and the group didn't start generating electricity until the closing Presto. Better late than never, but still.

In their defense, the Ariel is still a very, very young quartet. Its members are all in their early 20s, and their strengths, at this stage, are remarkable technical ability and ample supplies of youthful passion. But as the evening wore on, it was clear they burned like straw rather than coal, producing brilliant flashes of light but little lasting heat. Their reading of Alban Berg's String Quartet, Op. 3, for instance, was fiery, intelligent and exceptionally detailed - a treat to hear. Yet for all its interest, the performance felt thin and choreographed, like a staged fight where the punches look real but don't actually connect.

Things warmed up a bit when the much-admired violist Roger Tapping joined the Ariel for Mozart's Viola Quintet in D, K. 593, though it was hard to ignore the contrast between Tapping's seasoned, deliberate power - when he punches, he connects - and the earnest fiddling around him. But these are still early days for the Ariel, and as their passion deepens into insight, the group looks set to accomplish impressive things.

Trio Bolero at Westmoreland

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • January 31, 2011

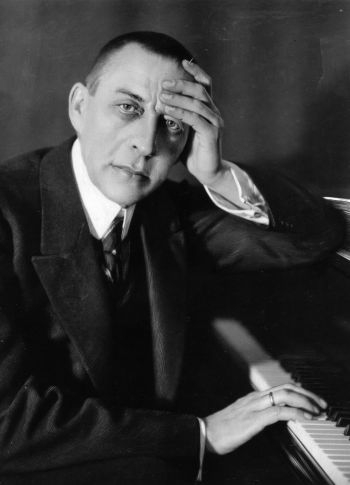

The classical repertoire isn't exactly overflowing with music for two guitars and cello, which presented a problem for guitarist Miroslav Loncar back in the early 1990s. Wanting to play chamber music with his guitarist wife, Natasa Klasinc, and their friend Rebekah Stark Johnson, a cellist, Loncar began transcribing music far from the beaten guitar path. The result was both new music and a unique ensemble - known as Trio Bolero - and on Saturday night at Westmoreland Congregational Church, the group pushed the guitar repertoire into intriguing new realms. Sergei RachmaninoffTranscriptions can be controversial; some say they distort a composer's vision, others say they open windows into familiar works. Loncar's transcriptions should persuade the doubters. They were skillfully done and most successful when he combined long, sweeping lines in the cello with delicate accompaniment from the guitars. Johnson has a fine romantic imagination and a rich, singing tone on the cello, and she used both to great effect in Rachmaninoff's soaring "Vocalise" and the elegant "Pavane" by Gabriel Faure.

Sergei RachmaninoffTranscriptions can be controversial; some say they distort a composer's vision, others say they open windows into familiar works. Loncar's transcriptions should persuade the doubters. They were skillfully done and most successful when he combined long, sweeping lines in the cello with delicate accompaniment from the guitars. Johnson has a fine romantic imagination and a rich, singing tone on the cello, and she used both to great effect in Rachmaninoff's soaring "Vocalise" and the elegant "Pavane" by Gabriel Faure.

Not everything came off quite as well, alas. The Bolero played cautiously for much of the evening, and works that should have been electrifying - such as Luigi Boccherini's Spanish-flavored "Introduction and Fandango" - came off as merely pleasant. A little more brio would have brought Bela Bartok's "Romanian Folk Dances" to life, and the group's polite reading of a suite drawn from "Carmen" did little justice to Bizet's passion. But there was much to love - a two-guitar account of George Gershwin's Three Piano Preludes was just gorgeous - and the concert (part of the John E. Marlow Guitar Series) brought some refreshing new material to the familiar guitar fare.

Aleksandr Haskin at the Terrace Theater

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • January 26, 2011

The classical flute world tends to be a bit . . . well, willowy, for lack of a better word. So it was a refreshing change of pace to head down to the Kennedy Center's Terrace Theater on Monday night to hear the Belarussian flutist Aleksandr Haskin, a young virtuoso who looks like he could also move that piano down the stairs for you, no problem. Aleksandr HaskinThe 26-year-old Haskin is the latest discovery of Young Concert Artists, and he turned out to be a musician of exceptional power and dramatic skill, completely in charge of his instrument. If he lacked the occasional refinement here and there, who cares - it only added to the impact.

Aleksandr HaskinThe 26-year-old Haskin is the latest discovery of Young Concert Artists, and he turned out to be a musician of exceptional power and dramatic skill, completely in charge of his instrument. If he lacked the occasional refinement here and there, who cares - it only added to the impact.

The program got off to a furious start with Ian Clarke's "The Great Train Race," a wild little tone painting for solo flute that draws on just about every extended technique in the book, from key taps to the almost impossible circular breathing. Playing from a half-crouch, Haskin brought high drama and an offhand charm to the thing, tossing off gasp-inspiring riffs and winning over the audience immediately.

A rather deliberate account of Bach's Flute Sonata in E Major followed, alas, but Haskin (accompanied by pianist Steven Beck) then worked a small miracle with Mozart's Andante in C Major, K. 315, turning in a reading that was both playful and completely natural.

Haskin displayed a lyrical side in Albert Franz Doppler's "Fantaisie Pastorale Hongroise" and the tender "Aria" from Otar Taktakishvili's Sonata for Flute and Piano. But the real depth of his playing came out in the second half of the program, particularly the personal and sharply imaginative accounts of Henri Dutilleux's "Sonatine," Bela Bartok's "Suite Paysanne Hongroise," and an engaging sonata by the little-known Russian composer Yuri Kornakov.

Haskin may have a little work to do before he joins the top ranks of the world's flutists - you got the feeling that he has yet to really unleash himself - but it was clear Monday that this is a musician of distinctive insight, well worth keeping an eye on.

Alessandrini's "Messiah" at the Kennedy Center

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • December 17, 2010

You have to hand it to "Messiah." George Frideric Handel's mighty oratorio has long been saddled with "holiday music" status, trundled out every year with the turkey, the mistletoe and (at our house, anyway) "Alvin and the Chipmunks Sing Christmas Hits." It's performed with such ear-numbing regularity - there are no fewer than 18 performances around town this month - that even die-hard Handel lovers could be excused for getting a little tired of the thing. Rinaldo AlessandriniBut despite all that, "Messiah" can still triumph magnificently, as the Italian conductor Rinaldo Alessandrini demonstrated in a trimmed-down, high-octane performance at the Kennedy Center Concert Hall on Thursday night. Alessandrini has made a name for himself over the past decade by rethinking and reinvigorating the early music repertoire, and he pared "Messiah" down to its essentials, using a mere 30 players from the National Symphony Orchestra, a similarly modest choir from the University of Maryland and the four soloists. The lean ensemble let Alessandrini fly through the work, sometimes at a devil-may-care tempo, with precise, beautifully articulated counterpoint and extraordinary detail. The usual large-forces "Messiah" can sometime bulldoze listeners into rapture, but Alessandrini's take was an exhilarating revelation.

Rinaldo AlessandriniBut despite all that, "Messiah" can still triumph magnificently, as the Italian conductor Rinaldo Alessandrini demonstrated in a trimmed-down, high-octane performance at the Kennedy Center Concert Hall on Thursday night. Alessandrini has made a name for himself over the past decade by rethinking and reinvigorating the early music repertoire, and he pared "Messiah" down to its essentials, using a mere 30 players from the National Symphony Orchestra, a similarly modest choir from the University of Maryland and the four soloists. The lean ensemble let Alessandrini fly through the work, sometimes at a devil-may-care tempo, with precise, beautifully articulated counterpoint and extraordinary detail. The usual large-forces "Messiah" can sometime bulldoze listeners into rapture, but Alessandrini's take was an exhilarating revelation.

Fine performances by the soloists added to the excitement, though the women outsung the men by a distinct margin. The Swedish soprano Klara Ek was particularly memorable (her voice is angelic, if you'll pardon the cliche), while mezzo Alisa Kolosova brought real dramatic power to her arias. The University of Maryland Concert Choir was impressive for such a young group, handling Alessandrini's exuberant direction with aplomb. In short, this is a must-hear performance, even if you think you're "Messiah"-ed out.

21st Century Consort at American Art Museum

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • December 6, 2010

M

aybe it’s not too surprising that we’re fascinated by water -- we’re mostly made up of the stuff, after all -- and composers in particular have always been drawn to it. Perhaps that’s because water is so much like music itself: constantly in motion, with profound depths and astounding power under a surface of infinite variety. Whatever the reason, water is still inspiring some of the most interesting music of our time, as the 21st Century Consort demonstrated in a remarkable concert at the American Art Museum on Saturday titled, “Unruly Landscapes.”

David FroomLoosely linked to “The Pond,” an ongoing exhibit of photographs by John Gossage, the program opened with “The Stream Flows” for solo violin, by the Chinese-American composer Bright Sheng. It was likeable enough, if traditional Chinese melodies tarted up in a modern idiom float your boat. Much more satisfying was David Froom’s Piano Trio No. 2 “Grenzen” -- a piece so full of life it almost bursts out of its skin – which received a spectacularly energetic and focused performance from Elisabeth Adkins on violin, Rachel Young on cello, and Lisa Emenheiser at the piano.

David FroomLoosely linked to “The Pond,” an ongoing exhibit of photographs by John Gossage, the program opened with “The Stream Flows” for solo violin, by the Chinese-American composer Bright Sheng. It was likeable enough, if traditional Chinese melodies tarted up in a modern idiom float your boat. Much more satisfying was David Froom’s Piano Trio No. 2 “Grenzen” -- a piece so full of life it almost bursts out of its skin – which received a spectacularly energetic and focused performance from Elisabeth Adkins on violin, Rachel Young on cello, and Lisa Emenheiser at the piano.

Donald CrockettEmenheiser is so diminutive that you half expect her to be blown away by the first strong breeze, but in fact she brought volcanic power to Alan Mandel’s “Steps to Mt Olympus,” whose title sums up its outsized gestures and almost Romantic thundering. Far more involving was Emenheiser’s reading of “Thoreau,” the last movement of Charles Ives’s “Concord” sonata. Not every pianist can make genuine sense of this confounding work, but Emenheiser infused it with delicate, ephemeral poetry; even Ives would have been impressed.

Donald CrockettEmenheiser is so diminutive that you half expect her to be blown away by the first strong breeze, but in fact she brought volcanic power to Alan Mandel’s “Steps to Mt Olympus,” whose title sums up its outsized gestures and almost Romantic thundering. Far more involving was Emenheiser’s reading of “Thoreau,” the last movement of Charles Ives’s “Concord” sonata. Not every pianist can make genuine sense of this confounding work, but Emenheiser infused it with delicate, ephemeral poetry; even Ives would have been impressed.

The real high points of the evening, though, were two gorgeous works by the West Coast composer Donald Crockett. There’s a great naturalness and effortlessness in Crockett’s writing, and “to be sung on the water” – a hymn-like duet performed by violinist Adkins, with Abigail Evans on viola – had a kind of distant, otherworldly glow, like nymphs singing from some underwater realm. His horn quintet “La Barca” (with Laurel Ohlson on horn) was far closer to the surface, but no less beautiful – a work of relentless inventiveness from a composer we really should hear more of.

Burning Bridge at the Freer Gallery

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • November 22, 2010

It’s not that often that you get to hear a tuba in a love duet with a two-stringed Chinese fiddle. Or a percussionist singing into his drums as if they were wind instruments. Or honky-tonk blues cranked out on the delicate Chinese lute known as the pipa. But these are more or less ordinary events in the sound world of violinist-composer Jason Kao Hwang, who brought a vast array of sonic wonders to the Freer Gallery on Friday night in his latest genre-straddling work, “Burning Bridge.”

Jason Kao HwangHwang is a naturally postmodern composer, and it was clear from the opening bars that “Bridge” (a five-part jazz suite running about an hour and a half) had a planetary-wide range of roots, from Chinese traditional music to New York’s downtown free jazz scene.

Jason Kao HwangHwang is a naturally postmodern composer, and it was clear from the opening bars that “Bridge” (a five-part jazz suite running about an hour and a half) had a planetary-wide range of roots, from Chinese traditional music to New York’s downtown free jazz scene.

But this wasn’t just jazz with a little hoisin sauce. Hwang has his finger firmly on the racing pulse of the 21st century, where everything is interconnected and boundaries of time and geography seem hopelessly quaint. If there’s a war cry for music of the new millennium, it might well be: Burn the bridges – there’s no going back.

And that’s what “Bridge” seemed to be about. The suite set out a framework of constantly evolving ideas in a loose narrative structure, within which the eight players improvised extensively. And much of the brilliance of Friday night’s performance, it must be said, belongs to the incendiary playing of Taylor Ho Bynum on cornet, Andrew Drury on drums, and Ken Filiano on bass (all members of Hwang’s Edge Quartet), joined by Joe Daley on tuba, Sun Li on pipa, Wang Guowei on erhu and the always impressive trombonist Steve Swell.