Contemporary Vietnamese Music at the Freer Gallery

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • November 12, 2010

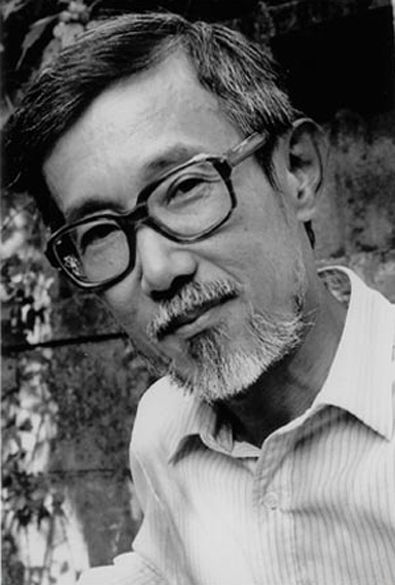

Ton-That TietSometimes it feels as if you only get to hear modernist Vietnamese music every, oh, thousand years or so. And in fact it took this year's millennium celebration of the founding of Hanoi to inspire a concert of mostly Vietnamese music at the Freer Gallery on Wednesday night. It was, as you might expect, a distinctive evening that reflected the region's ancient culture, its fateful interaction with the West, and the turmoil of recent decades. In short: music that blended East and West in ways that were meditative, sometimes violent, deeply moving and almost always thought-provoking.

Ton-That TietSometimes it feels as if you only get to hear modernist Vietnamese music every, oh, thousand years or so. And in fact it took this year's millennium celebration of the founding of Hanoi to inspire a concert of mostly Vietnamese music at the Freer Gallery on Wednesday night. It was, as you might expect, a distinctive evening that reflected the region's ancient culture, its fateful interaction with the West, and the turmoil of recent decades. In short: music that blended East and West in ways that were meditative, sometimes violent, deeply moving and almost always thought-provoking.

Among the highlights was Ton-That Tiet's "Chu Key I," which explored natural cycles using spare, diaphanous textures and extended techniques on the violin, viola and cello. Written in France in the late 1970s, it evoked a distinctly Asian sensibility in the vocabulary of European modernism, to great effect.

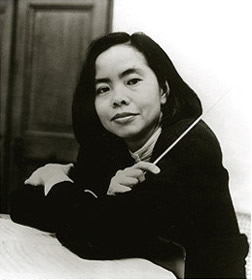

Two recent works by Vu Nhat Tan drew on traditional Vietnamese performance techniques and were played with great skill and sensitivity by Airi Yoshioka on violin and Madeleine Shapiro on cello. Particularly personal and vivid was P.Q. Phan's "Memoirs of a Lost Soul," built on his memories of growing up in the war years, the sounds of a children's musical game, and the death of a Vietnamese court singer during a performance. Bun-Ching LamThe gifted Vietnamese pianist Quynh Nguyen was the featured artist of the evening, and she turned in a fine performance of another work by Ton-That Tiet, "Three Pieces for Piano." Her account of Hoang Mi's more traditional "The Black Horse" was rousing, but the piece itself -- all rollicking rhythms and pentatonic scales -- sounded weirdly out of place in the program, like Twinkie Flambé in the middle of a sophisticated meal. The real gem of the evening, in fact, may have been Bun-Ching Lam's "Six Phenomena," a wonderfully engaging work built on the Buddhist Diamond Sutra, played with astounding sensitivity and insight by pianist Margaret Kampmeier.

Bun-Ching LamThe gifted Vietnamese pianist Quynh Nguyen was the featured artist of the evening, and she turned in a fine performance of another work by Ton-That Tiet, "Three Pieces for Piano." Her account of Hoang Mi's more traditional "The Black Horse" was rousing, but the piece itself -- all rollicking rhythms and pentatonic scales -- sounded weirdly out of place in the program, like Twinkie Flambé in the middle of a sophisticated meal. The real gem of the evening, in fact, may have been Bun-Ching Lam's "Six Phenomena," a wonderfully engaging work built on the Buddhist Diamond Sutra, played with astounding sensitivity and insight by pianist Margaret Kampmeier.

Charles Rosen & Christoph Genz at Clarice Smith

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • October 22, 2010

You almost have to go out of your way to avoid Robert Schumann these days; it's the 200th anniversary of the composer's birth, and his music is being celebrated as far as the ear can hear. Piano superstar András Schiff gave an all-Schumann recital on Wednesday night at Strathmore, but over at the Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center, an equally intriguing concert was underway -- one that stripped away centuries of convention to present original, rarely heard versions of two of Schumann's best-loved works.

The considerable brains behind the program (the highlight of the University of Maryland's four-day Schumann Festival, which ends Friday) belonged to none other than Charles Rosen, the eminent pianist, musicologist, author and all-around polymath who, having turned 83 in May, continues to probe more deeply and thoughtfully into music than just about any musician alive. Rosen teamed up with the terrific young German tenor Christoph Genz for the song cycle "Dichterliebe," restoring four songs that Schumann originally included but later took out (apparently for commercial reasons).

Charles RosenIt was a memorable performance. Genz has an extremely clear, light voice, effortless and natural throughout its range, and his take on the songs was expressive but never overcooked. Restoring the four songs, meanwhile, was simply brilliant; each was a small gem, and together they extended the dramatic arc and brought new depth and interest to the entire work.

Charles RosenIt was a memorable performance. Genz has an extremely clear, light voice, effortless and natural throughout its range, and his take on the songs was expressive but never overcooked. Restoring the four songs, meanwhile, was simply brilliant; each was a small gem, and together they extended the dramatic arc and brought new depth and interest to the entire work.

Rosen himself opened the evening with the original three-movement version of the Fantasia in C for Piano, Op. 17, which Schumann reworked and expanded after it was rejected by publishers. Rosen's technique -- just to get this out of the way -- isn't as powerful or precise as it was in his prime, but it was a fascinating reading nonetheless, deeply personal and shorn of all dross. When Charles Rosen plays, you can't help but listen; this is a musician who always has something important to say.

Arcanto Quartet at the Library of Congress

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • October 15, 2010

The Arcanto Quartet, put together less than a decade ago by four rising young European soloists, made an exacting and often ferocious American debut at the Library of Congress on Wednesday night, playing familiar works with an analytical edge so sharp it felt like it could draw blood. That's both good and bad, alas. In Mozart's Quartet in D Minor, K. 421, for instance, the Arcanto's focus on clarity and atomic-level

The Arcanto Quartetdetail was impressive, and while the piece was finely played and full of surprising insights, it also seemed to be missing much of its lyrical DNA. The result was a grab bag: The opening and closing movements had an elegant, lively bite, but the lovely Menuetto came off as so much canned charm.

The Arcanto Quartetdetail was impressive, and while the piece was finely played and full of surprising insights, it also seemed to be missing much of its lyrical DNA. The result was a grab bag: The opening and closing movements had an elegant, lively bite, but the lovely Menuetto came off as so much canned charm.

The Mozart was followed by Maurice Ravel's Quartet in F -- a great shimmering hallucination of a work, full of elusive colors and explosions of savagery, and the Arcanto gave it a clear-eyed reading that revealed details often missed by other quartets. But the hard-focus approach sacrificed much of the magic that makes the piece so seductive, and it was easier to respect the performance than to love it.

The Arcanto's formidable strengths shone to best advantage, though, in Bela Bartók's Quartet No. 5, which closed the program. It takes self-confidence to tackle this work here -- it was written for Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge herself, and premiered at the Library of Congress in 1935 -- but the players turned in a reading of absolutely stunning virtuosity and depth, so relentlessly powerful you didn't dare move for fear you might get hurt. This was extraordinary playing in every way, and a fine close to an intriguing, impressive debut.

Yuriy Mynenko at the Kennedy Center

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • October 9, 2010

The up-and-coming Ukrainian countertenor Yuriy Mynenko flew into town on Monday, jumped into rehearsals in Tuesday, and delivered a fine and sometimes extraordinary North American debut at the Terrace Theater on Thursday night. With superb control, a subtle sense of drama, excellent taste and stunning voice, Mynenko, 31, seems poised to join the ranks of the best of the world’s countertenors. That said, the recital (presented by Vocal Arts DC) stayed largely on the surface of the mostly-Baroque program, and only really caught fire here and there. That may have been due partly to normal debut jitters, but also to the rather dutiful and sometimes clumsy accompaniment by Gary Matthewman at the piano. The two had only met days before, and there didn’t seem to be much of the intuitive back-and-forth that lets a singer descend into the music and breathe it to life. While Mynenko’s delivery was always accomplished and exceptionally detailed — and the voice itself a thing of rare beauty — it rarely felt like the music was coming from any deep emotional core.

That said, the recital (presented by Vocal Arts DC) stayed largely on the surface of the mostly-Baroque program, and only really caught fire here and there. That may have been due partly to normal debut jitters, but also to the rather dutiful and sometimes clumsy accompaniment by Gary Matthewman at the piano. The two had only met days before, and there didn’t seem to be much of the intuitive back-and-forth that lets a singer descend into the music and breathe it to life. While Mynenko’s delivery was always accomplished and exceptionally detailed — and the voice itself a thing of rare beauty — it rarely felt like the music was coming from any deep emotional core.

Until, that is, the very end of the program. The evening had stayed within a fairly narrow stylistic range (from Purcell to Vivaldi, more or less, where the bulk of the countertenor repertoire lies), with fine if heavily accented accounts of Handel’s “Va tacito”, Gluck’s “J’ai perdu mon Euridice” and others. But when Mynenko shifted into a work from his own time and language — “Farewell, o world,” by the contemporary Ukrainian composer Valentin Silvestrov — any awkwardness vanished and the recital rose to an entirely new level. This was extraordinary singing in every way, and was followed by an equally moving a capella account of the Ukrainian national song — leaving little doubt that Mynenko is a talent to keep an eye on.

Defiant Requiem at the Kennedy Center

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • October 8, 2010

It's almost impossible to imagine, but in the dark, bleak years of 1943 and 1944, in the remote Nazi internment camp of Terezín, some of the most extraordinary musical performances of all time took place. Surviving brutal conditions and facing imminent death, a group of Jewish prisoners nevertheless formed a chorus and memorized (from a single score) Giuseppe Verdi's earthshaking "Messa da Requiem," performing it some 16 times in the camp. Murry Sidlin (r) with Rafael SchaechterThe Nazis considered it a wonderfully cruel joke -- the prisoners were "singing their own requiem," as one put it, and a Roman Catholic one at that. But the joke was on the Nazis, for the prisoners found in the work an epic gesture of defiance and hope that gave them a spiritual victory over their captors. As Rafael Schaechter, the group's director, put it: "We will sing to the Nazis what we cannot say to them."

Murry Sidlin (r) with Rafael SchaechterThe Nazis considered it a wonderfully cruel joke -- the prisoners were "singing their own requiem," as one put it, and a Roman Catholic one at that. But the joke was on the Nazis, for the prisoners found in the work an epic gesture of defiance and hope that gave them a spiritual victory over their captors. As Rafael Schaechter, the group's director, put it: "We will sing to the Nazis what we cannot say to them."

That story is at the heart of "Defiant Requiem: Verdi at Terezín," a multimedia concert-drama created by Murry Sidlin and given a spectacular, bare-knuckle performance Wednesday night at the Kennedy Center. The requiem itself is almost unbearably powerful on its own -- a searing tone poem about the end of the world, operatic in scope and run through with celestial melodies and cascades of fire and brimstone. But Sidlin's setting of the music, incorporating film of the camp, interviews with survivors, and actors describing the dramatic background, was handled with both dignity and power, and pushed the requiem to even more harrowing depths and exalting heights.

Major players were involved in the production, and Sidlin drew strong, committed performances from the Washington National Opera Orchestra, the City Choir of Washington, the Catholic University of America Chorus and four soloists, including the angel-voiced mezzo-soprano Janet Hopkins. Sidlin may have sacrificed precision for passion here and there (that eight-part fugue in the Sanctus is no picnic), but that hardly seems a fault. And when the singers filed out at the end, quietly intoning the "Oseh shalom" from the Jewish liturgy as a single violinist continued to play on the darkening stage, the effect was nothing less than electrifying.

Slowik and Ogg at the Museum of American History

By Stephen Brookes. • The Washington Post • September 28, 2010

One measure of a society's level of advancement, you might reasonably argue, is how much of the music of Johann Sebastian Bach it keeps within earshot. The Smithsonian Chamber Music Society, under the direction of the scholarly multi-instrumentalist Kenneth Slowik, is doing more than its share for civilization this season with a five-concert series exploring a range of Bach's sonatas, and the opening program on Sunday night showed just how many neglected wonders exist in this extraordinary legacy. The concert (in the Hall of Musical Instruments at the National Museum of American History) opened with Slowik joining with the eminent Dutch harpsichordist Jacques Ogg for Bach's Concerto in C for two harpsichords, BWV 1061. Some find the harpsichord a jangling, clattery menace to the ears -- and two of them a threat to sanity itself -- but this was a powerful, carefully detailed and deeply engaging performance. The instruments may share some of the credit: Ogg played a remarkably refined-sounding 1745 instrument made by Joannes Daniel Dulcken, while Slowik manned an exact copy crafted by Gaithersburg harpsichord-builder Mark Adler. The matching sonorities underpinned the fine and often dramatic interplay between the players.

The concert (in the Hall of Musical Instruments at the National Museum of American History) opened with Slowik joining with the eminent Dutch harpsichordist Jacques Ogg for Bach's Concerto in C for two harpsichords, BWV 1061. Some find the harpsichord a jangling, clattery menace to the ears -- and two of them a threat to sanity itself -- but this was a powerful, carefully detailed and deeply engaging performance. The instruments may share some of the credit: Ogg played a remarkably refined-sounding 1745 instrument made by Joannes Daniel Dulcken, while Slowik manned an exact copy crafted by Gaithersburg harpsichord-builder Mark Adler. The matching sonorities underpinned the fine and often dramatic interplay between the players.

The real focus of the evening, though, was Bach's three sonatas for the cello-like viola da gamba, BMW 1027, 1028 and 1029. These pieces have long lived in the shadow of the more celebrated suites for solo cello and aren't heard often, but they're real treasures that draw on an eclectic range of baroque styles, forms and gestures. Slowik turned in intense and absorbing performances in the best "historically informed" tradition, drawing a robust, somewhat astringent tone from a Matthias Hummel instrument from 1708 and a sweeter, lighter sound from an intricately inlaid instrument made by Joachim Tielke in 1691 -- a thing of such beauty that it received its own round of applause when Slowik unveiled it onstage.

Post Classical Ensemble's "Russian Gershwin"

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • September 27, 2010

It’s easy to see why the Post-Classical Ensemble would embrace George Gershwin. This most American of composers has long been under-appreciated at home, relegated to pops concerts for the sin of drawing on jazz and popular music. But Gershwin is overdue for a fresh look, and that’s the Ensemble’s specialty: turning familiar music on its head, providing context and fresh perspectives, and generally pulling the rug out from under listeners.  George GershwinThat was the strategy behind “The Russian Gershwin,” the Ensemble’s program on Friday night at the University of Maryland’s Clarice Smith Center. Russia, it turns out, has long been crazy for Gershwin and taken him far more seriously than America has, and the group brought two gifted young Russian pianists to show us why – and maybe shake us out of our preconceptions.

George GershwinThat was the strategy behind “The Russian Gershwin,” the Ensemble’s program on Friday night at the University of Maryland’s Clarice Smith Center. Russia, it turns out, has long been crazy for Gershwin and taken him far more seriously than America has, and the group brought two gifted young Russian pianists to show us why – and maybe shake us out of our preconceptions.

But make no mistake: This was not some weird, exiled Gershwin smelling of vodka and revolution. On the contrary; pianist Genadi Zagor opened the evening with an introspective and elegant improvisation on Gershwin’s Prelude No.2, then seamlessly slid into an ultra-sophisticated (and altogether gorgeous) account of the concerto-like Rhapsody in Blue. Zagor’s a superb pianist, and provided his own imaginative, very personal improvisations for the solo piano parts, walking the fine line between jazz and classical with perfect balance.

Vakhtang Kodanashvili took a jazzier and more extroverted approach to the Piano Concerto in F, a too rarely heard wonder from 1926. Kodanashvili’s lean, exuberant playing contrasted nicely with Zagor’s more lush approach, and -- backed by razor-sharp playing from the Ensemble, led by music director Angel Gil-Ordóñez – resulted in a terrifically exciting account, and an edge-of-seat Cuban Overture brought the program to a close. Was a distinctly “Russian” evening? Maybe – but to these ears, anyway, the personal trumped the national, and in the end it didn’t matter: Gershwin was Gershwin in any language.