Verdehr Trio at the Phillips Collection

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • November 18, 2008

T

he Verdehr Trio has become a perennial favorite at the Phillips Collection, where twice a year it presents new works -- which it has usually commissioned -- for its unusual combination of clarinet, piano and violin. The trio continued that tradition Sunday afternoon, dispatching a Mozart divertimento as an appetizer but quickly settling down to some intriguing new works written for it in the past few years.

Roberto SierraRick Sowash composed his "Memories of Corsica" for the Verdehr in 2007, and it's an engaging, colorful tone poem in the time-honored genre of musical travelogue. Opening with a depiction of the island's shimmering heat and empty villages, it quickly turns light and dancelike in the "Aromatic Breezes" section and closes with a forceful and even jaunty movement, full of exuberance and laughter.

Roberto SierraRick Sowash composed his "Memories of Corsica" for the Verdehr in 2007, and it's an engaging, colorful tone poem in the time-honored genre of musical travelogue. Opening with a depiction of the island's shimmering heat and empty villages, it quickly turns light and dancelike in the "Aromatic Breezes" section and closes with a forceful and even jaunty movement, full of exuberance and laughter.

The title of Roberto Sierra's 2008 "Recordando una Melodia Olvidada" translates as "Remembering a Forgotten Melody," so perhaps it was fitting that clarinetist Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr misplaced her music and had to rush offstage to find it. But with its subtle, beautifully observed perception of memory and its sudden shifts of perspective and time, it was a fascinating work, with the delirious intensity of a dream.

The Verdehr played, as always, with a fine combination of intellectual rigor and satisfying physicality and closed with yet another original commission, Bright Sheng's 2001 "Tibetan Dance." Interweaving Chinese, Tibetan and Western elements, it embodies Sheng's elegant postmodernist approach, and opens with a serene and ruminating prelude before moving into a minimalist love song and exploding into life in the final "Tibetan Dance" movement. Painted in brash, physical strokes, with pianist and violinist getting percussion sounds out of their instruments, it builds into a furious explosion of color -- a fascinating work, beautifully performed.

Helmut Lachenmann at the Library of Congress

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • November 15, 2008

T

here was tension in the air Thursday night at the Library of Congress. The young, forward-thinking Kuss Quartet was in town, and amid the cozy offerings of Haydn and Schubert was a work by Helmut Lachenmann, the hyper-modernist German composer whose ear-scorching works turn instruments into scraping, hissing noisemakers.

So we hunkered down with our fingers by our ears, ready for the onslaught. But Lachenmann's String Quartet No. 3 ("Grido") turned out to be an absolutely astounding and captivating piece of music, a marvel of invention and -- for all its strangeness -- undeniable beauty. Sure, Lachenmann pushes the sound palette into sometimes harsh areas. But he does it with such seamless logic and full-throttle imagination that the work unfolds as a gripping narrative from beginning to end.

So we hunkered down with our fingers by our ears, ready for the onslaught. But Lachenmann's String Quartet No. 3 ("Grido") turned out to be an absolutely astounding and captivating piece of music, a marvel of invention and -- for all its strangeness -- undeniable beauty. Sure, Lachenmann pushes the sound palette into sometimes harsh areas. But he does it with such seamless logic and full-throttle imagination that the work unfolds as a gripping narrative from beginning to end.

Not everyone agreed, alas ("the worst piece of music I've heard in 25 years," one listener observed during intermission). But Lachenmann is clearly a composer of extraordinary gifts, and "Grido" ranks -- to these ears anyway -- among the more notable new works of the past decade.

The rest of the evening, by comparison, felt like pudding -- comforting pieces played well but without a lot of poetry or depth. Haydn's String Quartet in D, Op. 64, "Lark," made for an amiable start to the concert, and if you like your Haydn slightly chilled, you were in luck. Schubert's String Quartet in A Minor (D. 804), "Rosamunde," followed the Lachenmann and was balm to many ears, but it, too, was an oddly restrained performance; warm and pretty but too polite to set the room on fire.

Arciuli Plays (Mostly) Native American Music

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • November 13, 2008

F

or the last three years, the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian has been mounting one of the more adventurous concert series in town, showcasing new classical music by Native American composers. Admit it -- you didn't know there was such stuff. But as Italian pianist Emanuele Arciuli demonstrated at the museum's elegant little Rasmuson Theater on Tuesday night, there's a little-known world of vibrant Native American music out there that defies categorization -- and deserves to be more widely heard.

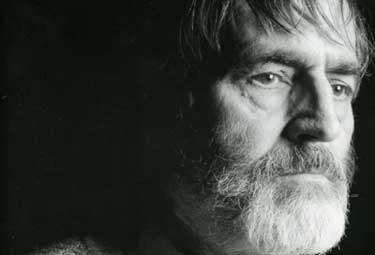

Louis BallardTake, for instance, Louis Ballard's "Osage Variations," which opened the evening. Like other works on the program, there was nothing overtly or obviously "Indian" about it; in fact, its musical language was fairly conventional. But the theme was gorgeous, and the variations wildly vivid, rich in melodic invention and dramatic power. Similarly, George Quincy, a Choctaw, showed a postmodernist edge in his three-part "The Release of the Choctaw Fire Bird," which blended 19th-century romanticism, contemporary angularity and folkish melodic fragments into a colorful and distinctive whole.

Louis BallardTake, for instance, Louis Ballard's "Osage Variations," which opened the evening. Like other works on the program, there was nothing overtly or obviously "Indian" about it; in fact, its musical language was fairly conventional. But the theme was gorgeous, and the variations wildly vivid, rich in melodic invention and dramatic power. Similarly, George Quincy, a Choctaw, showed a postmodernist edge in his three-part "The Release of the Choctaw Fire Bird," which blended 19th-century romanticism, contemporary angularity and folkish melodic fragments into a colorful and distinctive whole.

Quincy's piece evoked ancient myths (a theme throughout the evening), as did "Sky Bear," a dazzling, kinetic work by the Mohican Brent Michael Davids. The world premiere of Barbara Croall's "Inscription Rock" was equally intriguing but much darker in tone, using dampened strings to evoke elemental sounds. Raven Chacon, a Navajo (and the most avant-garde of the composers), contributed the spare, meditative "Nilchi Shada'ji Nalaghali" for piano and electronic sounds; an admirable piece, but hard to love.

Arciuli played well throughout but pulled out the stops only for "Phrygian Gates" by the non-Native American composer John Adams. A sonorous, hypnotic work from Adams's minimalist period in the 1970s, it's a gem of American piano music, and Arciuli played it -- there's no other word--magnificently.

Jonatha Brooke at the Birchmere

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • November 4, 2008

I

f there's some kind of fantasy lottery for folk singers, first prize would have to be the chance to co-write a song with Woody Guthrie. That's what happened to the gifted singer-songwriter Jonatha Brooke, who was invited this year to go through the archives of the iconic American folk singer (who died in 1967) and write songs based on his never-before-seen lyrics.

Brooke took the opportunity and ran with it, as she showed in a revelatory set at the Birchmere on Sunday night. Though she treated fans to some of her older gems ("Better After All," "Red Dress," "Ten Cent Wings"), the real focus was on the Guthrie-based songs from her new album "The Works" -- and it's some of her best work yet. Guthrie, it turns out, left some of his most intimate ideas behind on scraps of paper, and Brooke has turned them into smoldering love songs ("All You Gotta Do Is Touch Me"), explosive mixes of anger and regret ("My Sweet and Bitter Bowl") and even what she calls "totally a chick song," the tender "My Flowers Grow Green."

Brooke took the opportunity and ran with it, as she showed in a revelatory set at the Birchmere on Sunday night. Though she treated fans to some of her older gems ("Better After All," "Red Dress," "Ten Cent Wings"), the real focus was on the Guthrie-based songs from her new album "The Works" -- and it's some of her best work yet. Guthrie, it turns out, left some of his most intimate ideas behind on scraps of paper, and Brooke has turned them into smoldering love songs ("All You Gotta Do Is Touch Me"), explosive mixes of anger and regret ("My Sweet and Bitter Bowl") and even what she calls "totally a chick song," the tender "My Flowers Grow Green."

Brooke's singing isn't for everybody -- her range is limited, and her adenoidal twang grates after a while -- but her writing skills are acute, and there's a sly, seditious edge to her music that can be addictive. Guthrie's long-lost lyrics could hardly have found a better interpreter.

Opening for Brooke was the hyper-verbal Glen Phillips, formerly (and still occasionally) with Toad the Wet Sprocket. Phillips is recovering from an accident to his left arm that's hampered his guitar-playing, but an hour-long set of funny, biting material proved that his brain is still furiously intact. Nickel Creek's Sean Watkins -- there to do the heavy lifting, guitar-wise -- was an added bonus.

Tony Arnold at the Library of Congress

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • November 3, 2008

T

his year marks the centenary of the birth of Olivier Messiaen, one of the most strikingly original composers of the 20th century, and the Library of Congress has been marking the event with a series of concerts and lectures exploring his legacy. The celebration continued Saturday night with the fine soprano (and new-music specialist) Tony Arnold performing Messiaen's heady, turbulent and wildly colorful song cycle "Harawi (a Song of Love and Death)."

It takes a singer of considerable imagination to bring off this extravagant music. Inspired by the medieval love story of Tristan and Isolde, "Harawi" is both otherworldly and profoundly human, and incorporates bird song, Hindu rhythms, Peruvian melodies and Messiaen's own poetry to tell the story of lovers who meet their deaths. It's a huge work, rife with exotic textures and emotional complexities, and Arnold -- accompanied skillfully by Jacob Greenberg at the piano -- gave a superb and genuinely insightful account -- whether chanting ritualistically in "Doundou Tchil," evoking a state of quiet grandeur in "Adieu" or summoning near-breathtaking power in the magnificent "Repetition Planetaire."

It takes a singer of considerable imagination to bring off this extravagant music. Inspired by the medieval love story of Tristan and Isolde, "Harawi" is both otherworldly and profoundly human, and incorporates bird song, Hindu rhythms, Peruvian melodies and Messiaen's own poetry to tell the story of lovers who meet their deaths. It's a huge work, rife with exotic textures and emotional complexities, and Arnold -- accompanied skillfully by Jacob Greenberg at the piano -- gave a superb and genuinely insightful account -- whether chanting ritualistically in "Doundou Tchil," evoking a state of quiet grandeur in "Adieu" or summoning near-breathtaking power in the magnificent "Repetition Planetaire."

The Messiaen was the heart of the evening, but Arnold opened the program with a well-chosen selection of other "liebestod" songs that explored the intersection of love and death, from fluffy throwaways like Mozart's "Das Veilchen" to the gripping "Requiem for the Beloved" by Gyorgy Kurtag. The most engaging piece, though, may have been Thomas Adès's "Life Story," which explains, in amusing detail, why lovers sometimes burn themselves up in hotels.

Denyce Graves: That New Carmen Feel

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Times • November 2, 2008

F

ew mezzo-sopranos in history have ever sung Carmen - the untamable gypsy at the heart of Georges Bizet's opera - with as much fire and passion as Denyce Graves.

It's long been a signature role for the Washington native, and she's performed it hundreds of times in productions all over the world. She's so identified with it, she says, that she can't get off a concert stage without delivering at least one of its arias. This week Miss Graves takes the role up once again, in a Washington National Opera production that opens on Saturday.

It's long been a signature role for the Washington native, and she's performed it hundreds of times in productions all over the world. She's so identified with it, she says, that she can't get off a concert stage without delivering at least one of its arias. This week Miss Graves takes the role up once again, in a Washington National Opera production that opens on Saturday.

So she must be thoroughly, completely and totally sick of Carmen by now, right?

"No, no, no!" she insists, laughing.

"I'm always excited by a new production of Carmen, and I'm always challenged, theatrically and vocally," she says, speaking by phone from Chicago, where she's starring in a production of a new opera called "Margaret Garner," written for her by composer Richard Danielpour.

"There's so much stimulus going on, working with people I've never worked with before. And I'm always hearing something new in Carmen," she says. "It's a masterpiece; I always hear a different color in the orchestra, and there's always something to discover. And what I want is for people to come and say, 'I saw her do it 17 years ago, and it's much better now.'"

And in fact, this "Carmen" may prove to be Miss Graves' best yet - a mark of her triumph over career-threatening setbacks in her life.

Raised by a single mother in a small apartment in Southwest, the singer, now 44, never had it easy. But her talent was recognized early, and after graduating from the Duke Ellington School of the Arts and honing her technique at the New England Conservatory of Music, she quickly shot into the stratosphere in the 1990s. Armed with a spectacular voice and rare dramatic talent, she became one of the world's most celebrated opera stars - largely due to her indelible portrayals of Carmen.

But eight years ago, the fairy-tale life turned dark. As her 15-year marriage to classical guitarist David Perry collapsed, she coped with depression, debilitating headaches and serious voice problems that threatened her career. Bleeding from the vocal cords, she completely lost her voice at one point and had to stop performing. As if that weren't bad enough, her doctors cautioned her against ever having children, even suggesting a hysterectomy.

Instead, Graves fought back. She had surgery for a fibroid tumor, divorced Mr. Perry and married again, this time to the French composer Vincent Thomas. Her voice came back, stronger than ever. And despite the pessimism of her doctors, she became pregnant and now has a healthy 4-year-old daughter, Ella.

Life is beautiful now, she says. But she doesn't regret having to endure a series of crises to get there.

"Those things are very important - they put your priorities in order," she says. "You can choose to learn something from the experiences, and I'm much more aware and conscious of so many things, now. I'm much more centered. I try not to be in the past, or anywhere but right now. So I consider that a blessing."

That new sense of herself seems to be pushing Miss Graves in new directions, too. She's doing mostly concerts and recitals these days, rather than opera productions, which she says gives her a chance to explore music that she's always wanted to do: Francis Poulenc's "Metamorphoses," for instance, or Claude Debussy's "Chansons de Bilitis."

"I'm doing material people probably don't know me for, and I'm looking forward to expanding that repertoire," she says. "And I feel stronger and more confident than I ever, ever have."

But the real reason she prefers concerts over opera productions, she admits, is that it gives her more time for her most challenging role yet - being a mother.

"I'm so grateful for Ella," she says. "She used to travel with me, but she's growing - she's got her own activities now.

"When she was really little, she used to take me to the piano by the hand and say, 'Sit, Mommy. Sing.' And now whenever I sing she says, 'Oh, Mom, please! I'm trying to do something - and I can't concentrate with all that noise!'"

•••••

WHAT: The Washington National Opera's production of George Bizet's "Carmen," starring mezzo-soprano Denyce Graves as Carmen (Laura Brioli will sing the role Nov. 12 and 18), and Thiago Arancam and Brandon Jovanovich alternating as Don Jose. Directed by David Gately with Julius Rudel conducting. In French with English supertitles.

WHEN: November 8, 10 at 7p.m.; Nov. 12, 14, 18, 19 at 7:30 p.m.; Nov. 16 at 2 p.m.

Fireworks at the Library of Congress

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • November 1, 2008

I

I

f there's a patron saint of chamber music, it's undoubtedly Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, whose support of this neglected genre was so strong she even built the Library of Congress an auditorium to play it in. Coolidge would have turned a sprightly 144 on Thursday, and the library marked the occasion with a performance by the Fireworks Ensemble -- a young octet every bit as adventurous and ahead of the curve as the revered lady herself.

The classically trained Fireworks players say they're out to "redefine the chamber music experience for a new generation of listeners" by expanding the repertoire into new areas, and this we can only applaud. The world of chamber music can feel airless, smothered in the kind of tonier-than-thou connoisseurship that makes sensible people flee for the hills, but the Fireworks players threw open the windows and let the air in. Playing everything from electric guitars to an orange kazoo, they romped through Norwegian folk songs, a Bollywood film score, some baroque dance music and a Duke Ellington classic, even taking a stab at the dance club electronica of Aphex Twin -- cleverly reverse-engineered for acoustic instruments.

It was as fresh and fun as it sounds, and when it worked, it worked beautifully. You lose a certain authenticity when, for instance, you arrange a Haydn string quartet for electric guitar and soprano saxophone, but it's well worth hearing at least once. And there were some fine solos, particularly by violinist Kathryn Eberle. Chamber music may not have been "redefined," but it definitely got a kick in the pants -- and Coolidge herself would probably have enjoyed the party.