Verge Ensemble at the Corcoran

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • September 21, 2010

The venerable Verge Ensemble, which has been rattling D.C.'s musical cage since 1973 with smart, innovative programs of new music, opened its 37th season on Sunday at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, and it's clear the group has lost neither its adventurous bite nor its commitment to local composers.

Take, for instance, the superb "Hazmats Sextet" by the Peabody Conservatory's David Smooke, which opened the program. Smooke has some of the most uninhibited brain cells around, and the work, which he describes as "birds flying through a continually fracturing landscape," evoked a kaleidoscopic sonic universe where anything could happen. It was one of those rare pieces you fall in love with from the get-go. If this is hazardous musical material, send more.Ken UenoThere was a different kind of radioactivity in Ken Ueno's rather severe "Sabinium," for electronic tape with a video realization by animator Harvey Goldman. Ueno recorded the sounds of bursting bath bubbles, convolved them with battle noises and built the results into a sometimes-fragile, sometimes-brutal but always poetic piece of noise music. Goldman's animation -- primordial cell-like structures interacting in a sort of cosmic soup -- elegantly interpreted the score and referenced the underlying story of the Sabine women, and in spite of its mercilessly monochromatic and minimalist materials, "Sabinium" was fascinating throughout. (Watch it here.)

The redoubtable Lina Bahn turned in a very smart performance of David Felder's "Another Face," a tour de force for solo violin that explores issues of identity with acute psychological insight; it was like listening to someone struggle out of the maze of their own self. The world premiere of Wesley Fuller's "phases/cycles for viola and computer" fared less well, despite fine playing from John Pickford Richards. While engaging at first -- it sounded like some tender, inter-species love song -- the work sagged under a computer-generated track that was often alarmingly cartoonish, as if R2-D2 were bleeping and pinging in the wings. But the program closed strongly with "Resonance," a lyrical and beautifully crafted piece for flute, piano and cello from American University's Eric Slegowski.

Surf's Up!

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • January 4, 2009

If you need someone to dominate the power of the oceans, I'm the wrong person to call. Those surfers who glide effortlessly down 12-foot tsunamis, rippling their muscles and getting tanner with every passing wave? That's not me. I'm the pale, lazy guy sitting back on the beach -- the one under the umbrella with a book, a cooler and a lifetime supply of SPF 100.

Freights Bay, BarbadosSo what was I doing this brilliant July morning, standing on a cliff in Barbados with a surfboard under my arm? Down below, the surf was crashing into the rocks with a menacing roar. By my side, five other surfing novices, from their early 20s to somewhere in their 50s, were huddled around our instructor, Melanie Pitcher, and we were listening closely. She was teaching us how not to get killed.

Freights Bay, BarbadosSo what was I doing this brilliant July morning, standing on a cliff in Barbados with a surfboard under my arm? Down below, the surf was crashing into the rocks with a menacing roar. By my side, five other surfing novices, from their early 20s to somewhere in their 50s, were huddled around our instructor, Melanie Pitcher, and we were listening closely. She was teaching us how not to get killed.

"The surfboard is the most dangerous thing out there," said Melanie, waving at the surging Atlantic. "Just don't be on the wrong side of the surfboard when a wave crashes on you, or you'll get nailed. And try not to jump onto any sharp coral. You probably won't remember any of this when you're out there, but don't worry about it. It's going to be fun!"

We looked at one another nervously. I'd signed up for this class at the last minute, on one of those middle-aged "things you must do before you die" impulses. I knew I'd never be hanging 10 in Malibu or riding the Banzai Pipeline in Oahu, but I didn't care. All I wanted was to get upright, yell "Cowabunga!" and then go home to impress my children with my awesome surfer-dude coolness.

And Barbados seemed as good a place as any to get started. It's still well off the beaten path, but with some of the best and most consistent waves in the Caribbean, it's becoming a magnet for serious surfers. And there are some spectacular surf spots, such as the legendary Soup Bowl on the island's rugged east coast, which, frankly, is scary just to look at.

But we were down at the "beginners" beach, Freights Bay, at the southern end of the island, where the waves are gentle and no one really expects much of you. On a grassy bluff overlooking the water, Melanie walked us through Surfing 101, which is basically just paddling on your stomach, then getting upright on the board into proper surfing position.

Goofy foot and Melanie, safe on dry landIt turns out there are two ways to do this. You can (a) push up off the board with your toes, leaping with feline agility into a perfectly balanced pose; or (b) clamber your way clumsily upright, flailing your arms and hoping for the best.

Goofy foot and Melanie, safe on dry landIt turns out there are two ways to do this. You can (a) push up off the board with your toes, leaping with feline agility into a perfectly balanced pose; or (b) clamber your way clumsily upright, flailing your arms and hoping for the best.

Melanie demonstrated the first method. It looked easy. The 20-somethings tried it, and all floated into position as if they'd grown up in Malibu.

Then the rest of us gave it a shot.

"Oh, look!" said Melanie, after I'd taken a minute to lumber into a wobbly, semi-vertical pose. "You're a Goofy foot!"

I looked at her, stricken. "Don't worry," she said. "It's just a term for people who put their right foot forward on the board, rather than their left." I nodded, but still . . . Goofy foot? That couldn't be good.

But there wasn't time to be humiliated. The surf was up (as we surfers say), so we climbed down to a narrow strip of beach where Melanie launched us into the ocean one by one, like little ducklings. We paddled out past the breaking waves and practiced sitting on our boards, bobbing happily as the swells, no more than a few feet high, lifted us up and down.

So far, as midlife adventures go, this one was working out pretty well. Is there anything that embodies carefree youth more than surfing, with its easy, endless summers and melanoma-free tans? I may have been a few decades late to the party, but here I finally was. The sun was golden, the waves were warm and green, there were girls in bikinis and once in a while a gigantic sea turtle would swim by. It was surfing as imagined by Walt Disney. I could have bobbed there all day.

Then, of course, it all had to end.

"Okay, who's ready?" shouted Melanie, and I paddled over. She grabbed my board, and, with one eye on the incoming waves, gave me a final piece of advice. "Don't forget to . . . " she started to shout, but a wave had caught the board and I was off in a wild rush. Paddling madly, I picked up speed and somehow pushed myself forward on the board, my feet a confused tangle, my arms pinwheeling in the air.

And suddenly, for one brief glorious moment, I was up.

And just as suddenly, down again, the board crashing around my ears in the foaming water. But the feeling was incredible. I'd been vertical for only a nanosecond or two, but it didn't matter. Goofy-footed or not, I had surfed. Some hole in my life that I didn't even know was there had been filled -- filled, I might add, with awesome surfer-dude coolness. It felt good.

And now I can go back to my umbrella.

•••••

GETTING THERE: American and US Airways offer convenient flight schedules from Reagan National to Bridgetown, Barbados; price starts at about $560 round trip. American also offers good connections from BWI; price starts at about $600 round trip. An additional baggage fee is sometimes charged for surfboards; check with the airlines for details.

WHEN TO GO: Serious surfers go between October and March, when there are usually two- to 12-foot waves in the northern part of the island, and up to six feet on the other beaches. Summer visitors get the advantage of near-empty beaches as well as the annual Crop Over Festival, the island's biggest (and most boisterous) cultural event.

WHERE TO SURF: The coral reefs that surround Barbados and the constant trade winds create a variety of surfing conditions, from the mild waves of the west coast to the more dramatic surf of the east. The most challenging spot is the Soup Bowl in the beach town of Bathsheba. Other east coast spots for the experienced surfer include Barclays Park, North Point and Parlor. Newbies may want to start at the gentler beaches in the south, particularly Freights Bay, Brandon Beach, Accra Beach and South Point. Melanie Pitcher of Barbados Surf Trips (246 262-1099; http://www.surfbarbados.com) designs surfing vacations for all levels and can arrange lodging and transportation. Packages start at $425 a week.

WHERE TO STAY: Accommodations are scarce in the agreeably laid-back town of Bathsheba, but try the New Edgewater Hotel (866 978-5067, http://www.newedgewater.com), where winter rates, Dec. 15-April 14, are $116 to $212 per night. Most of the better hotels are on the island's west coast. Big spenders flock to the Sandy Lane Hotel (St. James Parish, 246 444-2000, http://www.sandylane.com), where rooms start at $1,000 a night in summer. But we had a wonderful stay at the Crane (St. Philip Parish, 246 423-6220, http://www.thecrane.com), a historic hotel on a spectacular bluff on the southeast coast. Winter rates start at $210, and it's close to all the surfing spots. Farther south, the Little Arches Hotel (Christchurch Parish, 246 420-4689, http://www.littlearches.com) is a charming and popular boutique hotel, where winter rates start at $245.

WHERE TO EAT: No trip is complete without the Friday-night fish fry at Oistin's Bay on the south coast. You grab a picnic table and order fresh grilled fish from one of the dozens of small open-air restaurants there. It's noisy, crowded and fun. Try the flying fish. If you're looking for upscale dining, though, try The Tides (Holetown, http://www.tidesbarbados.com) or The Cliff (St. James Parish, http://www.thecliffbarbados.com), which is pricey but famous for its cuisine. Or check out Thai and Japanese food at Zen (in the Crane Hotel), which features giggling Barbados waitresses in kimonos.

Olivier Messiaen, Visionary

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • December 28, 2008

The French composer Olivier Messiaen is walking through a tangled field of wildflowers outside Paris, listening. It’s shortly after dawn, and a cold sun is just starting to break through a line of far-off trees. Suddenly a trilling cry comes through the air. “That’s a song thrush,” he says, pulling out a pad of music paper and jotting down the melody in quick, decisive strokes of a pencil. “One of the best singers -- perhaps the most beautiful singer -- in France.”

Olivier Messiaen with studentsThe scene (from “The Crystal Liturgy,” a recent documentary on Messiaen) is revealing. One of the most innovative, multifaceted and utterly unique composers of the 20th Century, Messiaen drew deeply from nature, famously transcribing bird songs from all over the world and building works of astonishing power and beauty from them. But he was also a profound Catholic who explored mysticism and sexuality through music, a sensualist who perceived sounds as radiant colors, and a musician of limitless curiosity who drew on influences from ancient Japanese gagagku music to medieval isorhythms, to develop one of the most distinctive musical voices of the century.

Olivier Messiaen with studentsThe scene (from “The Crystal Liturgy,” a recent documentary on Messiaen) is revealing. One of the most innovative, multifaceted and utterly unique composers of the 20th Century, Messiaen drew deeply from nature, famously transcribing bird songs from all over the world and building works of astonishing power and beauty from them. But he was also a profound Catholic who explored mysticism and sexuality through music, a sensualist who perceived sounds as radiant colors, and a musician of limitless curiosity who drew on influences from ancient Japanese gagagku music to medieval isorhythms, to develop one of the most distinctive musical voices of the century.

“Messiaen’s impact on music in the 20th century has been colossal,” says Peter Hill of the University of Sheffield, a pianist and scholar who co-authored the definitive biography of the composer. “And interest in his work is spreading like wildfire. It’s become a kind of global phenomenon, and it doesn’t look like it’s going to go away.”

Not during 2008, at any rate. This year marks the centenary of Messiaen’s birth, and there’s been a steady crescendo of his music around the world, from near-countless performances of the well-known “Quartet for the End of Time” to rarely heard masterpieces like the opera “St. Francis of Assisi.” Some of the performances have verged on the spectacular – the epic “Et exspecto resurrectionem mortuorum” was even played outdoors this summer, as the composer intended, at the Meije glacier in France – and virtually his entire oeuvre is being released on weighty, multiple-CD sets. And in the District this fall, a series of concerts will showcase some of the Messiaen’s most stunning works.

“I knew this year would be busy,” says Hill. “But it’s really gotten quite crazy.”

The composer in 1945Despite the surge of interest, Messiaen remains what he was for most of his life – an intriguing but relentlessly elusive figure. Born on December 10, 1908, his life appeared almost numbingly ordinary. Mild mannered, drab and somewhat fashion-challenged in appearance, he lived in near-Spartan simplicity with his wife (the pianist Yvonne Loriod), teaching at the Paris Conservatory (where his students included Pierre Boulez, Iannis Xenakis, Karlheinz Stockhausen and other luminaries of postwar music) and serving as the organist at the Église de la Trinité in Paris from 1931 until his death in 1992.

The composer in 1945Despite the surge of interest, Messiaen remains what he was for most of his life – an intriguing but relentlessly elusive figure. Born on December 10, 1908, his life appeared almost numbingly ordinary. Mild mannered, drab and somewhat fashion-challenged in appearance, he lived in near-Spartan simplicity with his wife (the pianist Yvonne Loriod), teaching at the Paris Conservatory (where his students included Pierre Boulez, Iannis Xenakis, Karlheinz Stockhausen and other luminaries of postwar music) and serving as the organist at the Église de la Trinité in Paris from 1931 until his death in 1992.

But the bland exterior concealed a musician of extraordinary originality and depth – qualities that first became apparent during World War II when, after being captured by the Germans in 1940, he was interned in a prisoner of war camp in the Silesian town of Gorlitz. Working under arduous conditions, he wrote one of the most searching works of the 20th century, the “Quartet for the End of Time,” and gave it a near-mythic premiere in the freezing camp on January 15, 1941 before an audience of hundreds of his fellow prisoners.

The work had little in common with the raging, mournful anti-war works being written by other modernist composers at the time. With its echoes of Balinese gamelan music, evocations of birds awakening and a rhythms deliberately designed to stop forward movement, the Quartet was a confounding work – sensual, otherworldly, deeply spiritual and intensely moving. It sent – and still sends – shock waves through modern music, and quickly achieved almost iconic status; it’s now thought to be the most-performed piece of 20th century chamber music in the world.

Messiaen notating bird callsAnd there was more to come. After his release, Messiaen returned to Paris and continued to write, exploring exotic sources from Hindu chants to antique Greek modes. But the result was no mere pastiche. Messiaen filtered his eclectic tastes through what he called “the marvelous aspects of the [Catholic] faith,” and a series of remarkable works began to pour out: “Visions de l’amen” (1943), “Vingt Regards sur l’enfant Jesus” (1944), the song cycle “Harawi” (1944), and the sprawling, ten-movement “Turangalila-Symphonie” (1946-48) – a work of almost lurid color and sensuality that used chord clusters, exotic percussion and the rare, wailing sound of the Ondes Martenot.

Messiaen notating bird callsAnd there was more to come. After his release, Messiaen returned to Paris and continued to write, exploring exotic sources from Hindu chants to antique Greek modes. But the result was no mere pastiche. Messiaen filtered his eclectic tastes through what he called “the marvelous aspects of the [Catholic] faith,” and a series of remarkable works began to pour out: “Visions de l’amen” (1943), “Vingt Regards sur l’enfant Jesus” (1944), the song cycle “Harawi” (1944), and the sprawling, ten-movement “Turangalila-Symphonie” (1946-48) – a work of almost lurid color and sensuality that used chord clusters, exotic percussion and the rare, wailing sound of the Ondes Martenot.

Messiaen, in fact, was a visionary in a literal sense. He perceived sounds as distinct colors, and wrote as if he were painting with them. The theories and orthodoxies of the serialist movement that dominated postwar music held little appeal for him. “I’m modal, tonal, serial – as you like,” he once told an interviewer. “In fact, I’m colorful. And when you think you hear a series of tones, even triads, you’re wrong. Those are colors.”

But increasingly important in his music was Messiaen’s interest in the natural world. He began collecting bird songs in Paris, becoming a self-described “passionate ornithologist,” and using the transcriptions as material for his music. A riveting 1952 work for flute and piano work called “Le Merle Noir” (The Blackbird) was quickly followed by larger works, including 1953’s "Réveil des oiseaux" (Awakening of the birds) for orchestra, “Oiseaux exotiques” (Exotic birds) from 1955-56, and “Catalogue d'oiseaux” (Catalog of the birds) from 1958 – works that continue to grow in popularity.

“Nature has retained a purity, an exuberance, a freshness we have lost,” he once observed. “Nature never displays anything in bad taste; you’ll never find a mistake in lighting or coloration or, in bird songs, an error in rhythm, melody, or counterpoint.”

And that philosophy, says Hill, may be part of what keeps drawing new audiences to Messiaen.

“The great nature poet that is Messiaen is something that’s very much in tune with the ideals of the modern world,” he says. “It has a great appeal to audiences who are looking for a kind of idealism beyond everyday life. He was a very universal, eclectic musician who nonetheless managed to keep his personal voice. And there’s enormous interest among young performers in taking up his music.”

Musicians from Marlboro at the Freer Gallery

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • December 12, 2008

The annual “Musicians from Marlboro” concerts at the Freer Gallery are among the most invigorating events of the classical season. Dozens of astoundingly gifted young virtuosos, all hand-picked from the Marlboro Music Festival in Vermont, blow into the gallery’s Meyer Auditorium every winter for three performances that radiate vitality and freshness – qualities sometimes missing from their more seasoned elders.

And so it was on Wednesday night, when the first installment of Marlborians opened the series with Leos Janacek’s String Quartet No. 1 ("Kreutzer Sonata"). It’s an almost brutally passionate work that, played well, will take the skin off your ears, and the players turned in a suitably hot-blooded performance. It was, perhaps, a bit too hot-blooded at times -- its emotions spelled out in capital letters, then underlined, then italicized. But even if the excesses swept away the subtleties here and there, this was playing of daring, conviction and real insight. You could do worse.

And so it was on Wednesday night, when the first installment of Marlborians opened the series with Leos Janacek’s String Quartet No. 1 ("Kreutzer Sonata"). It’s an almost brutally passionate work that, played well, will take the skin off your ears, and the players turned in a suitably hot-blooded performance. It was, perhaps, a bit too hot-blooded at times -- its emotions spelled out in capital letters, then underlined, then italicized. But even if the excesses swept away the subtleties here and there, this was playing of daring, conviction and real insight. You could do worse.

The tireless Jessica Lee, who had played second fiddle in the Janacek, took the lead with a new crew of players for Mozart’s String Quintet in E flat Major, K. 614. Elegant and fiendishly difficult, it’s not as drop-dead beautiful as Mozart’s earlier quintets, but the players brought out the complex polyphony with clarity and grace. More engaging was Mendelssohn’s lush Octet in E flat Major, Opus 20, which violinist Scott St. John led in grand Romantic style. Impeccable ensemble work, unbridled energy and boatloads of virtuosity produced an electrifying performance – and whetted appetites for the next Marlboro concert in February.

Tori Ensemble at the Freer

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • December 12, 2008

Amid all the painful attempts to modernize traditional music -- the jazzed-up Mozart, the rocked-out Verdi, the desperate pastiches that try to pass for "new" - there sometimes comes a work that reinvents traditional music with such authenticity, power and originality that all you can do is drink it in with grateful ears.

Yoon Jeong HeoThat's what happened on Tuesday night at the Freer Gallery, when the Tori Ensemble (a sui generis group comprising three Korean virtuosos and three luminaries of New York's cutting-edge music scene) performed a spectacular and utterly beautiful new work called "The Five Directions." A collaborative effort based on Asian conceptions of circulation, balance, harmony and discord, its roots went deep into ancient Korean musical traditions: from the hypnotic rhythms of shamanistic rituals to the strange, compelling story-telling vocal music called panosri.

Yoon Jeong HeoThat's what happened on Tuesday night at the Freer Gallery, when the Tori Ensemble (a sui generis group comprising three Korean virtuosos and three luminaries of New York's cutting-edge music scene) performed a spectacular and utterly beautiful new work called "The Five Directions." A collaborative effort based on Asian conceptions of circulation, balance, harmony and discord, its roots went deep into ancient Korean musical traditions: from the hypnotic rhythms of shamanistic rituals to the strange, compelling story-telling vocal music called panosri.

But this was music fully of the 21st century, in all its global, post-modernist glory. Set in five movements, it unfolded fluently and imaginatively across a kaleidoscopic range of styles, anchored in tradition but speaking an exuberant new language. Meditative solos on the geomungo - the Korean zither - would give way to racing drum duets, bamboo flutes would rise and fall with impossible delicacy; a singer would send her clear, penetrating voice over a field of electronic percussion.

It was an astounding performance, with the effect of a profound journey across centuries of culture that led firmly to the current day, and the audience exploded into cheers at the end. Superb performances by geomungo player Yoon Jeong Heo, singer Kwon Soon Kang, drummer Young Chi Min, together with the New York contingent -- reeds player Ned Rothenberg, cellist Erik Friedlander and percussionist Satoshi Takeishi - made this one of the most satisfying performances of new music this season.

21st Century Consort at the Smithsonian

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • December 7, 2008

Those of us who love contemporary music -- that ear-bending stuff sandwiched on the program between the Haydn and Schubert, when listeners are pinned helplessly in their seats -- often urge nonbelievers to listen as if looking at modern art. Think of music as a canvas, we say; imagine the abstract shapes as a Frankenthaler, the explosive power as a Kline, the novel mix of ideas as a Rauschenberg.

Kaija SaariahoSometimes, believe it or not, that actually works. And it's fascinating to hear a concert designed around specific artists, as the 21st Century Consort did Saturday at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, focusing on the museum's current exhibition of paintings by Georgia O'Keeffe and photographs by Ansel Adams.

Kaija SaariahoSometimes, believe it or not, that actually works. And it's fascinating to hear a concert designed around specific artists, as the 21st Century Consort did Saturday at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, focusing on the museum's current exhibition of paintings by Georgia O'Keeffe and photographs by Ansel Adams.

The program opened with Aaron Copland's Piano Fantasy, and seemed to be a direct nod to Adams. Drawn largely in bold strokes with spare, often terse gestures (much like Adams's photographs), the work was given a robust performance by Lisa Emenheiser.

The rest of the concert focused on three of the more interesting non-dead-white-male composers around: the gifted Augusta Read Thomas, known for her kinetic, dancelike works; an adventurous Finn named Kaija Sarriaho; and the grande dame of American music, Joan Tower.

Thomas's music inspires love bordering on madness in some of us, but her ". . . a circle around the sun . . ."/"Moon Jig" pairing got a rather tentative performance -- or perhaps it was just outshone by a completely stunning work called "Petals" for amplified cello and electronics by Sarriaho. Played superbly by Rachel Young at the far reaches of her instrument, it was as coloristic and involving as -- why not? -- an O'Keeffe painting. Emenheiser and violinist Elisabeth Adkins joined Young to close the program in style with three engaging works by Tower, including the smile-inducing "And . . . They're Off."

Canadians at the Terrace Theater

By Stephen Brookes • The Washington Post • December 4, 2008

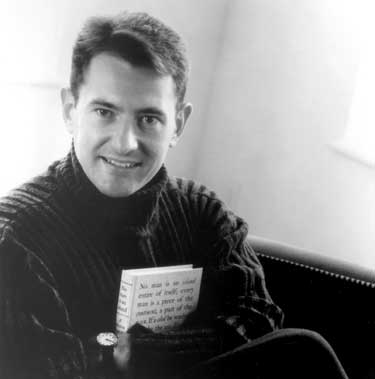

Brett Polegato

Brett Polegato

At the risk of stereotyping Canada (and who can resist?), it's fair to say that our neighbor to the north is not usually associated with the dark, demon-driven soul-searching of the romantic composers of 19th-century Germany. That notwithstanding, three fine young musicians from the Great White North descended upon the Terrace Theater on Tuesday for an evening of lieder that ranged from Brahms's sublime luminosity to Hugo Wolf's equally sublime anguish.

The Canadians in question were Susan Platts, a mezzo-soprano with a clear, dark voice and a polished but somewhat mannered style; Brett Polegato, a baritone with less polish but a more interesting brain; and their accompanist, the expressive Rena Sharon. After opening with a duet (Brahms's charming "Vergebliches Ständchen Op. 84 No. 4"), the two singers alternated onstage, Platts anchoring her end around Gustav Mahler's "Lieder Eines Fahrenden Gesellen" and lighter works by Brahms and Clara Schumann.

Susan PlattsIt was a well-chosen program, allowing Platts to display her beautifully controlled mezzo across its considerable range. But for all her skill, it was rarely a gripping performance. Platts skated prettily over the music's depths rather than plunging headlong into them, and even Mahler's wrenching "Ich hab' ein gluhend Messer" (which opens with the cry "I have a red hot knife, a knife in my breast") seemed bloodless; passion pressed under shatterproof glass.

Susan PlattsIt was a well-chosen program, allowing Platts to display her beautifully controlled mezzo across its considerable range. But for all her skill, it was rarely a gripping performance. Platts skated prettily over the music's depths rather than plunging headlong into them, and even Mahler's wrenching "Ich hab' ein gluhend Messer" (which opens with the cry "I have a red hot knife, a knife in my breast") seemed bloodless; passion pressed under shatterproof glass.

Polegato was a different story. While his singing was less secure than that of Platts (his diction, among other things, could use a little honing), his interpretations had far more natural vitality and power. Wolf's "Gesange des Harfners" was a fine essay in the dark shadows of the human heart, and Robert Schumann's eight-song "Liederkreis Op. 24," although not quite as involving, showed that Polegato is an artist to be reckoned with.